Return to Sender: The Next ‘Dear Stranger’ Swaps Letters on Memory

Image: Oregon Humanities

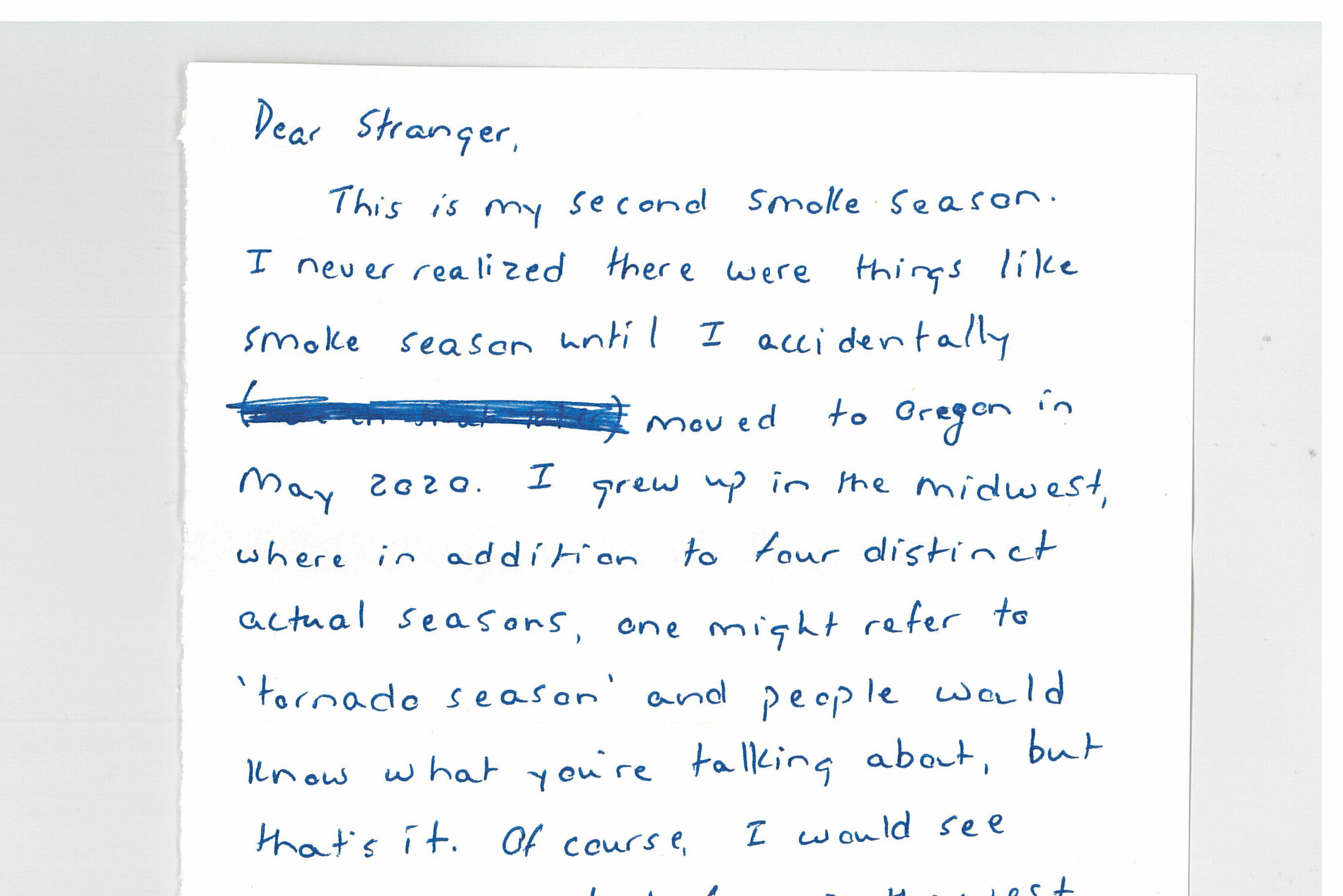

Since its inception in 2014, more than 1,100 Oregonians have written letters to people they’ve never met, through an Oregon Humanities project entitled Dear Stranger. Ben Waterhouse, who edits the organization’s magazine and developed the project, says he initially thought its value would be in the catharsis of writing to a stranger; in practice, it’s receiving letters that has had the biggest impact on those involved.

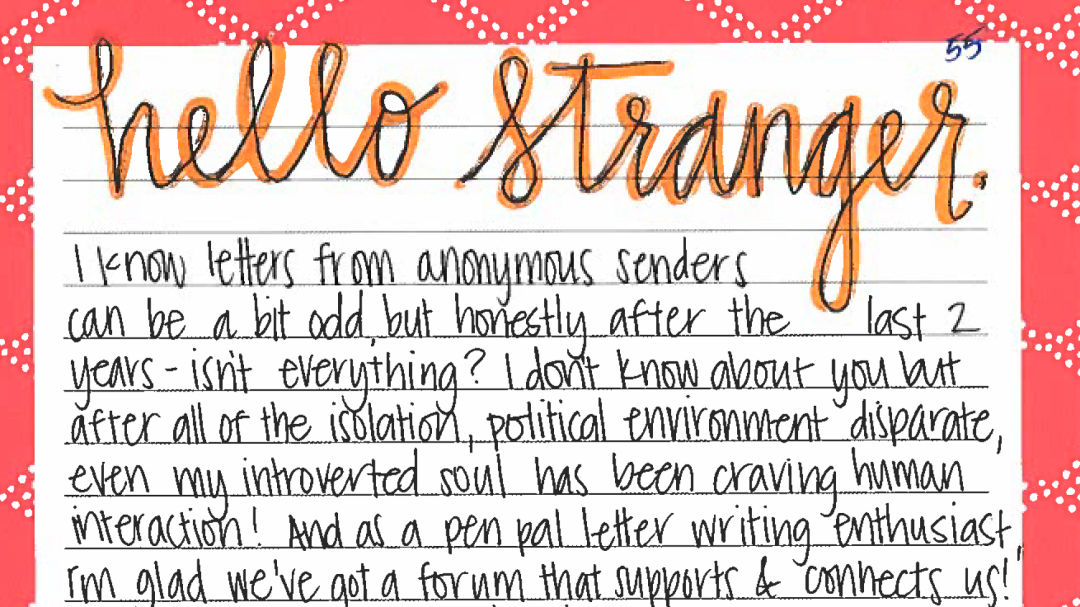

Dear Stranger was relaunched in a time of pandemic isolation, and was a boon for many. But with social interactions back in our lives, the organizers have turned the focus to memory. Submissions are due this Halloween responding to the prompt: What’s worth remembering, how do you make and process memories, and how do you document them?

Waterhouse was initially inspired by the Post Secret blog, the early 2000s website that anonymously published readers' concise and often lewd secrets. The difference is that Dear Stranger is predicated on exchange: write a letter, receive a letter.

In developing the project, Waterhouse also wondered if a different angle into the feeling of semi-anonymous writing was possible—writing for an unknown audience, but without the salaciousness of online platforms. “Dear Stranger removes the voyeuristic element,” he says. In contrast with, say, Craigslist’s missed connections, there is no compendium or public platform of letters. Excerpts are occasionally published in the magazine, with permission. But the project is based on connection, not an end result or product.

“People find the connection through the exchange of letters much more valuable than the writing,” says Waterhouse. “So, it quickly moved from being an extension of the magazine to being about connecting people across space and differences of experience. I don't think—actually, I know the majority of people who participate in Dear Stranger are not subscribers.”

The magazine has a public message board where participants share their experiences with the project. Julie, a Portlander, cast a light on the gaps such a project can bridge, stating that her stranger sounded melancholy, “a notable contrast from my mood,” she wrote. The contrasting perspective was refreshing, she adds, helping to show the “differences in how people see the world. Not good, not bad, just different.” Susan, who wrote in all the way from Southhampton, Massachusetts, said this spring that the project made her feel both “included and hopeful [that] people were experiencing many of [her] same feelings.”

Some offer literary-review-style blurbs: “Dear Stranger has the potential to offer a thought-provoking self-examination, and invites meaningful community-building opportunities,” wrote Karen from Central Oregon. Some, advice on participating in the physical medium that has become so foreign to us: “Happy to help anyone who wants to write, or help with letters in any way,” wrote Tamra of Gresham.

Image: Oregon Humanities

Waterhouse says he’s been in touch with both a high school teacher and a community college professor who are using this round of Dear Stranger as a class assignment. Justin Hocking, a memoirist and professor of nonfiction writing at Portland State University, says the project reminds him of a quote from Rebecca Solnit’s 2013 book The Faraway Nearby: “Writing is saying to no one and to everyone the things it is not possible to say to someone.”

Hocking says he’s included epistolary assignments in many of his syllabi. Usually, he asks students to write to an abstract entity—the ocean, someone you know but aren’t actually going to send it to, or Cheryl Strayed’s once-anonymous Rumpus column “Dear Sugar.” “Sometimes you need a stranger,” says Hocking. “Opening up to a stranger who doesn’t know anything about your life—and knowing what you say to them isn’t gonna get back around to anyone that you know—can be freeing and liberating.”

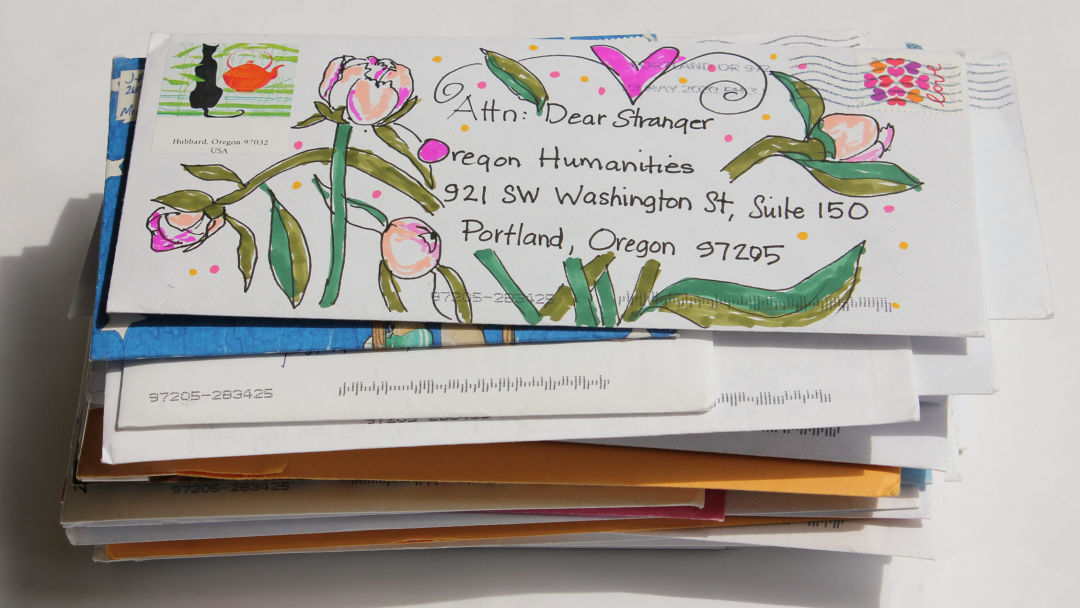

Most crowd-sourced projects comparable to Dear Stranger end in some form of public-facing media: a book, an art installation, a message board. Waterhouse points to a Harvard project that studied loneliness which published letters anonymously as a collection. Similarly, an epistolary novel can grip readers with its sense of what human connection truly feels like. “There’s a volume of correspondence. You see this huge pile of people’s thoughts and contributions. That is not the end goal of this project. It’s really about individual connection,” says Waterhouse.

Oregon Humanities is accepting memory letters through October 31. Want to participate? Address your letters as follows (and head to the Oregon Humanities website for more details):

Attn: Dear Stranger

Oregon Humanities

610 SW Alder St, Suite 1111

Portland, OR 97205