Johnny Franco Wants to Lick the City’s Wounds with His Guitar

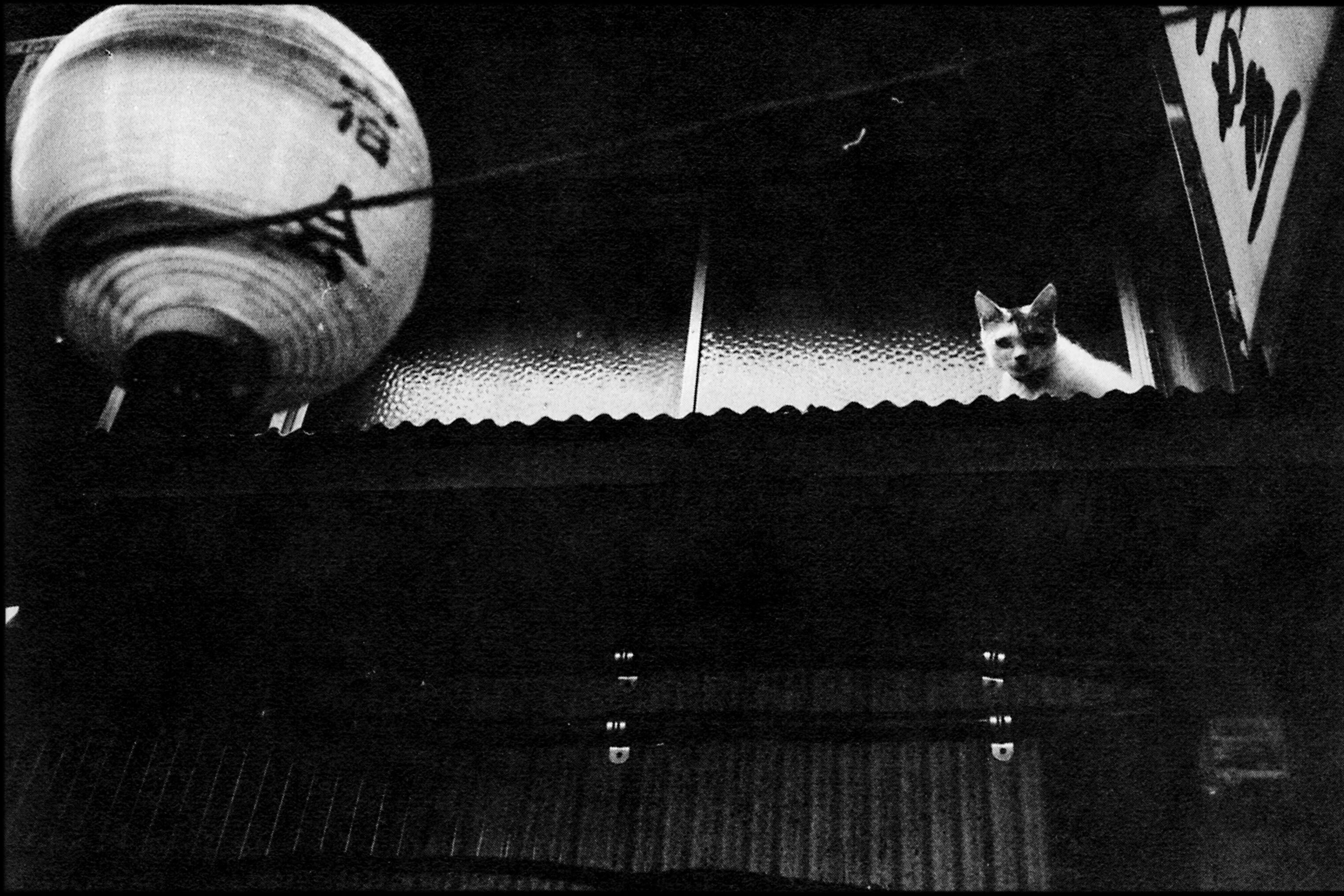

Image: Michael Raines

For the past three years, charmed Brazilian rocker Johnny Franco has played both host and star of a free concert series at Laurelhurst Park. Crowds of all ages and creeds gather with their dogs every Thursday, April through September, to see the self-styled “professional entertainer.” The shows feel spontaneous, yet too fleshed-out to be street performances. They’re fueled by Franco’s jangly, Brazilian beat–inflected rock ’n’ roll and punk spirit, and rest on his unimpeachable charisma. Franco and various bands play on a makeshift stage under the stars. There are drums and amplifiers, even a PA system, but also twinkly lights, a scrappy tent, and no bouncers, wristbands, or stamps to speak of. It’s Johnny’s show; nobody’s asking questions.

Despite the horn section, it wasn’t until one evening last September, at the start of the 24th show of a 24-show season, that park rangers noticed. Turns out each show required a $2,000 permit. The city turned a blind eye that night but required Franco get official permitting for 2024.

When I met Franco, 29, and his brother Domenico “Dom” Franco (together they make up the band Johnny Franco and His Real Brother Dom) for coffee in early March, they both wore vintage blazers over shirts buttoned low, with pleated trousers hitting their leather Adidas. Johnny is tall and svelte, and speaks as smoothly as he sings, with a streetwise confidence. Dom wears a curly mop of hair and, at 21, has a less practiced persona than his older brother—except when he’s playing guitar.

Johnny moved to Portland from São Paulo first, in 2018. He was undocumented, and earned his living busking while he pursued a green card, which he got a year later. When Dom immigrated in 2020, the brothers launched “Curbside Serenade”: on Instagram, they offered themselves as on-call troubadours, ready to deliver a socially distanced performance at parks, on porches, or atop balconies—anywhere you like. Fellow street musician David Pollack pitched growing the business, and the trio quickly mounted a cast of nine Serenaders, built out a website, and sold more than 200 serenades in the first year.

One gig brought the brothers to Laurelhurst Park, live music for a customer’s picnic date. It started intimate, but quickly drew a crowd. They came back the next Thursday, hoping for—and finding—the same ad hoc audience. Then the next. And the next. And so on for three years running.

Image: Michael Raines

Johnny Franco is no doubt Portland’s most glamorous busker. But he’s seen fits of success on a bigger stage. In 2020 he signed with producer Sterling Fox, who’s collaborated with Lana Del Rey and Britney Spears, and released an EP, Experience Report #1, on Fox’s label. Together, the brothers played on the popular YouTube series “Jam in the Van,” in 2022.

“It’s the oldest story in America, right?” Franco says between sips of coffee. “The foreign family sends their young ones to work in America to see if we can get a good future for everybody.” During a recent concert, he told a packed house at the Southeast Portland venue Lollipop Shoppe to post about the show online, “so our family back home will think we’re famous.”

Franco’s grasps at fame are always delivered with a wink. Above all, he says his mission is to “bring people out there and really make it alive.” Through free public concerts, he wants to “lick the wounds” the city’s suffered in recent years, delivering joy to neglected downtown corners in the afternoons, and to Laurelhurst Park, a recent site of class turmoil around the houselessness crisis, at night.

His shows match the scale of long-standing events like Comedy in the Park and the Original Practice Shakespeare Festival. The city parks department even has a program designed to help independent organizers put on shows as part of its Summer Free for All, which provides event staff, restrooms, permits, sound engineering, marketing—a package deal that starts at $1,000 per show, half of the standard permit fee.

But the magic of Curbside Serenades doesn’t quite fit that box. They bring their own equipment, run their own sound. Preserving what Franco calls the “liberating essence of the event” is paramount. Permits are standard procedure. The city, Dom says, was “very nice about it.” (A representative from Portland Parks and Recreation explained that the permit fees help fund general park maintenance.) But even at the subsidized rate of $1,000 a pop, the costs aren’t feasible, especially when factoring in the Monday concerts at Mt Tabor Park that the group added along the way.

Image: Michael Raines

Refashioning Curbside Serenade into a nonprofit substantially lowered permitting rates, all the way to about $3,200 for the year at Laurelhurst, which they’re currently fundraising through GoFundMe. They also hope to pass some of the raised money on to performers (privately scheduled serenades are paid, but public concerts rely on tips). They’ve reserved dates with the city to kick off this season April 18, but they’ll have to come up with the cash first.

Speaking of cash: the Francos’ latest single, “Ones and Pennies,” tells of their earliest fundraising methods. The Dylanesque strummer, released March 2, is an ode to downtown regulars like BirdMan and Blue Mike—people who, as Johnny says, “really took us in.” It’s also intensely autobiographical. “We’re takin’ ones and pennies,” the brothers wail in harmony on the chorus, at once acknowledging their struggle and pushing through with an ever-sunny spirit. “Five, ten, twenties / and your cigarettes, too.”

They’ll take what you’ve got, but they always give back more.