Last Supper

On a warm spring evening in 2001 in a Northeast Portland bungalow, two dozen strangers–artists, architects, designers, copywriters and philanthropists–were seated around a long table MacGyvered together from two-by-fours and old foam-core doors. Candles flickered; guests chatted about summer plans and delighted in the acquaintances that they, perhaps not so coincidentally, had in common. But their attention mostly centered around a slender, blond-haired, blue-eyed 24-year-old, Michael Hebb, the evening’s host, who busied himself by making introductions and pouring more wine, darting in and out of the kitchen, where his girlfriend, Naomi Pomeroy, a pixieish, glitter-eyed 26-year-old, put the finishing touches on the night’s dinner: platters of local salmon baked with fleur de sel, caramelized turnips, and artichokes simmered with lemon, herbs and garlic.

Diners passed the food to one another for what seemed like hours. By 10, the party was winding down. While guests ferried dishes to the kitchen, Hebb asked them to throw $5 into the bowl by the door before they left. Despite all appearances, this was a business plan, not a party. It had begun with a home-based catering business for which, according to Pomeroy, shrimp were thawed in the bathtub and dishes were hosed on the lawn. Now it was expanding into clandestine, invitation-only dinners dubbed "Family Supper." This had been the first.

Within a few years Michael and Naomi Hebberoy–the couple famously merged their surnames in 2002–would, with the help of some of Portland’s wealthiest citizens, build the upstart venture into what came to be known as the Ripe restaurant empire, a gastronomic supernova so bright it dazzled (some might say blinded) the city. Its gleam reached as far as New York, where the press praised Portland’s rise to culinary power; W magazine even dubbed Ripe’s creators "the prince and princess of the Pacific Northwest food scene."

Which is perhaps why the city was so astonished last April when Ripe imploded, Michael Hebberoy disappeared, and the Hebberoys’ impending divorce received prominent headlines in the Oregonian and other local publications. What the city had perceived to be an entirely new culinary and artistic business model (some used the word "revolution"), complete with its own celebrities, had curdled into disappointment, lawsuits and schadenfreude. Portland, in some ways, had been duped. An illusionist had appeared out of nowhere, made a moderate-sized city with a sizable appetite appear to be a top-tier cultural and culinary metropolis, and then stolen away in the night.

Michael Hebb grew up in Bend and Portland, the son of a father who was 71 when Hebb was born, and who, Hebb claims, "played polo … developed the Salishan Spa & Golf Resort … ‘groomed’ [Oregon Senator Mark] Hatfield … and was the first person to bring a Jersey cow to the United States," among other things. (Several of Hebb’s assertions about his father’s past are at best unverifiable; the last is unequivocally untrue.) His father died when Michael was 12 years old. In 1997, after Michael had dabbled in design and architecture at Reed College and Portland State University, he assumed duties as catering manager at Elephant’s Deli in Northwest Portland. By night he bused dishes at Zefiro restaurant in Nob Hill, where Michael says he was more interested in making social connections than in cleaning plates.

That same year, Naomi Pomeroy, a petite, dark-haired girl who grew up in Corvallis with a jeweler father and a stay-at-home mother, had graduated from Lewis & Clark but was unsure what to do with her history degree. "I’d lived in India for a year and studied cooking, but I didn’t realize it was something I could do as a job," she says, though she landed the occasional catering gig and bused tables at Il Piatto on SE Ankeny St. Then she met Hebb. "He would come into the restaurant, and we both loved dancing so we’d go out to clubs," she says. "He invited me to a potluck dinner at his house, and I pretty much never left."

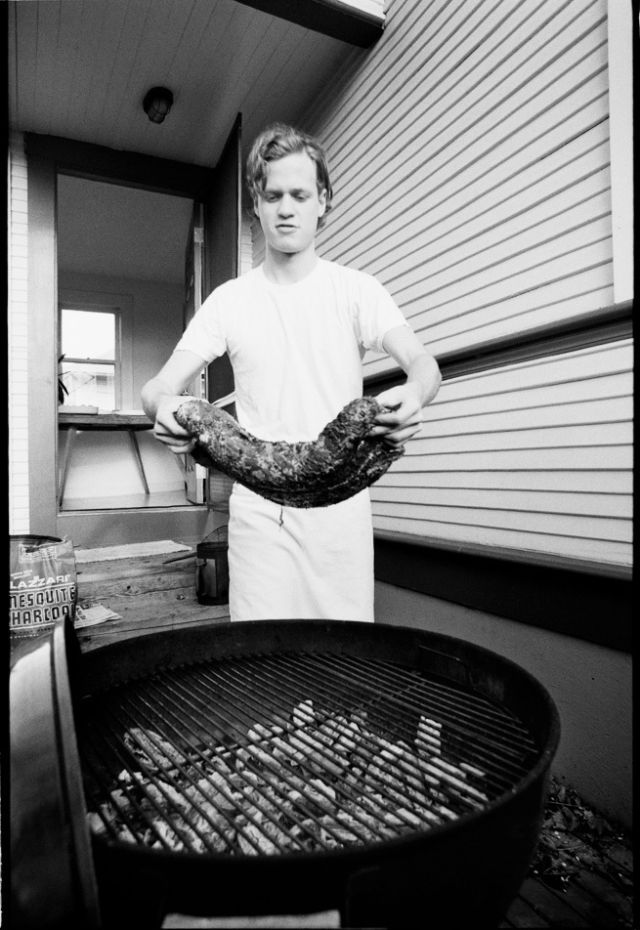

Image: Basil Childers

Except to travel to Southeast Asia, again to study cooking. Upon her return Pomeroy moved in with Hebb, who began hatching a business plan. "He was very inspired by the meals I cooked at home. He said, ‘Between you and me, this is the perfect combination: You can cook; it’s always great; and I’m the same with people and marketing.’"

In 1999 they christened their as-yet-to-be-defined food business Ripe. In order to land their first catering gig, for an alternative bridal show they’d seen advertised in a fabric store, Hebb says he bluffed their credentials by telling the organizers they were Portland’s next big caterers. "Delusion is key. It’s the fog of war," Hebb says he told Pomeroy. "If anyone asks how busy we are, we are exceptionally busy."

Hebb’s tactics worked. By 2000, the Ripe duo were catering events for Portland’s burgeoning arts organizations and galleries out of the basement of their Northeast rental, which, says Pomeroy, they never had inspected by the Health Department.

In March 2001, the couple began to host their multicourse Family Suppers, in their living room. Guests–usually around 25–ate whatever Pomeroy felt like cooking. Meanwhile, Hebb orchestrated the social scene they were creating.

"We were all supposed to bring our own chair and deposit money in a bowl on our way out the door–it was all so new for us," says Lizzy Caston, a consultant who was then an urban planner with the Portland Development Commission and who attended the first Family Supper. "I got seduced right away. You have to understand: For years, Portlanders suffered from an inferiority complex. The suppers were by e-mail invitation only, and it made people feel like they were part of something really cool."

Within a year, the suppers had increased in frequency from one to six times a week, and had gone from being larded with friends to hosting an e-mail list that eventually grew to more than 12,000 names. By 2002, the couple had taken a new composite surname (they wouldn’t marry until 2004): Hebberoy, which they’d given to their daughter, born in 2000. They’d also found a new space for Family Supper, in the red-brick Gotham Building, set on an industrial stretch of N Interstate Ave where, in a few years, a new MAX light-rail line would be installed.

With no outside funding, they signed a lease, and on the first floor opened an unadorned coffee shop, where customers could peruse artfully scattered copies of Dwell while sipping their lattes. Four nights a week, they hosted Family Suppers in an upstairs dining room that, in the shadow of the Fremont Bridge, felt like the most urbane and happening gathering in Portland, provided you knew how to find it: Its location was deliberately kept a secret, with only an unmarked rear entrance and zero signage.

People found it. Portland luminaries from Vera Katz to Gus Van Sant passed platters of roasted chicken and fresh sardines to one another. The suppers, the price of which had increased to $25, plus more for wine, dessert and tip, began to sell out weeks and then months in advance. With the hiring of two additional chefs, both previously of Zefiro, the menus became more ambitious and more spontaneous.

Image: Basil Childers

The media took notice. Articles about Family Supper appeared in Better Homes & Gardens and Sunset, and local journalists became regulars, including Caryn Brooks, then Willamette Week‘s arts editor, who esteemed Family Supper "a pleasant break from the predictable and pedigreed restaurant experiences around town."

"I once asked [Michael Hebberoy] about his goals and how he planned to expand," Brooks recently wrote in an e-mail from New York, where she is now an editor for the Associated Press. "He then proceeded to hold forth on a tip he had picked up from a book written by a restaurateur he admired. ’When it comes to the media,’ he said, ‘you have to fluff them, feed them and fuck them.’"

Clearly, this wasn’t business-as-usual in mostly polite Portland, nor was Michael Hebberoy’s proclivity for spending more of his time tending to the social mise-en-sc’ne than cultivating the culinary mise-en-place. And yet the attention he received as a result brought good things from afar. Morgan Brownlow, who’d cooked at Bizou and Rubicon in San Francisco, arrived back home in Portland in 2002. Tall, blond and boyish at 31, he sent out "100 résumés" to local restaurants, but no one responded, despite his pedigreed kitchen chops, until Hebberoy called, asking, "What the hell are you doing in Portland?" He hired Brownlow onto the Family Supper team soon after.

Tommy Habetz, who’d worked 90-hour weeks in New York City with Mario Batali and Bobby Flay, joined Family Supper soon after. As was the case with Brownlow, his star-studded résumé had also been largely ignored in Portland, nor was Habetz impressed with the food he’d eaten here.

"I’d been in Portland for over a year, and honestly I was not excited about the cooks I met," he says. "Then I got to cook at [Family Supper]. When you see cooks who can really cook like that, it makes you so excited."

By summer 2003, no Portland restaurant was getting as much local or national attention in the media as Family Supper, although there was no actual restaurant, a "formulaic" venture the Hebberoys insisted they had no interest in running.

But when Brownlow was offered a job in California, the Hebberoys finally gave in, proposing to open a dining room of Brownlow’s own to keep him in town–a great coup in the eyes of their growing roster of fans, including Eastside waterfront developer Brad Malsin, who offered them free rent in an empty warehouse on SE Water Ave until the restaurant was completed. Michael Hebberoy, who says that at the time he had no collateral or credit, applied for a bank loan and was swiftly rejected. Undaunted, he appealed to some of the better-heeled customers who’d helped make Family Supper such an overnight success.

David Howitt, a 38-year-old former corporate counsel for Adidas–who with his wife, Heather, had started a "small venture fund" after she sold her company, Oregon Chai, in 2004 for $75 million–would become Ripe’s largest investor.

"I don’t even want to call us investors; we were more like patrons," says Howitt. "Like when you’re supporting an artist."

Hebberoy, however, did not have an artist’s proclivity toward poverty: In 10 days, he would raise $260,000, with a business plan Howitt says was, "essentially, a one-page manifesto. He basically said, ’You’ll get paid back on a monthly basis–your money plus interest. And you’ll get free food and VIP status.’"

In addition to Howitt, Hebberoy wooed a growing list of patrons, which included several PICA board members as well as other prominent arts philanthropists around town. "We felt that Portland needed this," says Howitt. "Portland often gets this categorization: that you can smoke pot and drink coffee, but we don’t really care if we’re doing anything that’s cutting-edge. But there are a lot of us who want to push the envelope, in the Portland way. Michael’s appeal was, ‘Guys, this is not the French Laundry or something in New York; we’re going to put us on the map in a way that is authentic to us.’"

In fall 2003, the Hebberoys and Brownlow formed an LLC, allocating half the restaurant’s equity to Brownlow and half to the Hebberoys. Neither party had put up a dime. Before the interior had even been completed, the Hebberoys threw a pre-opening party. Investors and friends gathered; members of local band Pink Martini played; and the Peter Greenaway film The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover was projected on one wall. The buzz was already deafening by February 2004, when Clarklewis, the city’s first truly industrial-chic restaurant, finally opened. It was the sort of dining room that one regularly saw in Soho, but that had never before appeared in Portland. On opening night, when a fuse blew, Brownlow cooked by candlelight.

Clarklewis was an overnight sensation. And if customers had to acclimate themselves to retro portion sizes ("small," "large" or "family"), hipper-than-thou servers, "recommended reading" printed on the back of the menu, deafening acoustics and a level of lighting more suited to the bedroom than the dining room, Brownlow’s cooking lent Clarklewis the undeniable substance it needed. The ever-changing menu offered dishes such as mussels with shaved fennel and conserve of chiles; a "peasant salad" of bitter lettuces, roasted fresh-cured pancetta and coarse-shaved parmesan; and silken house-made pastas. During the day, whole hogs and lambs were butchered in the open kitchen, in full view of the ladies who lunched.

Whether in response to Brownlow’s extraordinary food, Michael Hebberoy’s fluffing of the press or some combination of the two, the Oregonian named Clarklewis its Restaurant of the Year less than three months after it opened. Within the year, the Hebberoys and Tommy Habetz had partnered to create a new restaurant venture–Gotham Building Tavern–which would be housed in the space then occupied by the coffee shop they’d been running. Troy MacLarty, formerly of Chez Panisse in Berkeley, took over at Family Supper, his presence helping to incite a near conflagration of press, including an eight-page spread in the January 2006 issue of Food & Wine in which Michael Hebberoy was dubbed a "food provocateur."

Meanwhile, Hebberoy continued to expand the scope of the Ripe empire, by hiring novelist Matthew Stadler as his "writer in residence"; bringing in late-night DJs at Gotham Building Tavern; throwing more and more clandestine suppers at undisclosed locations; and conceptualizing a new line of seasonal GBT (as in Gotham Building Tavern) gins with the Portland distillery Medoyeff.

By all appearances, the Hebberoys had lassoed the moon. It was around this time, however, that Michael Hebberoy started talking about his next project, a book titled Kill the Restaurant, and, whether consciously or unconsciously, he hit on the idea of starting with his own.

"I remember being on our honeymoon in Puerto Vallarta, right after Clarklewis opened," he says. "I was lying by the pool reading Jeremiah Towers’s tell-all [California Dish], about how the whole Stars restaurant empire starts to crumble, and Naomi’s like, ‘I hope that never happens to us.’ And I just looked off and saw it across the sky: It will fall in exactly the same way."

On April 27, 2006, it did just that. The previous night, at a "Glass Dinner"–one of many underground culinary events Michael Hebberoy was constantly orchestrating, in this case at Esque, a glassblowing studio–Naomi Hebberoy says Michael told her that Ripe’s finances, which he’d always overseen, were irretrievably down the toilet, and that he didn’t know where to get more money. Michael’s emotional state wasn’t news to Naomi–the couple had been living apart for nine months, and he’d been increasingly manic, she says–but the fact that they would not make payroll for Ripe’s 95 employees was a surprise to Naomi. Moreover, Michael informed her that he was leaving town; she’d have to find a way out of the mess on her own.

In the morning, Naomi Hebberoy phoned the key figures still in Ripe’s nucleus, and "within 10 minutes" found herself in Howitt’s office along with Brownlow, Habetz and various lawyers. After they reviewed the financial situation, it was decided that all the businesses in the Gotham Building–the catering operation, Family Supper and the tavern–would close that day. That left Clarklewis, a restaurant Naomi (who’d spent the past two years cooking at and managing Gotham, Family Supper and their catering business) had never been involved with, except as a partner-on-paper. Soon the Hebberoys would lose their equity, as would Brownlow, who for the time being decided to stay on as chef.

Howitt, who became the new sole proprietor of Clarklewis, offered Habetz ownership of Gotham, provided he take on all its existing debts. Habetz declined. (Troy MacLarty had left Family Supper several months earlier, after Michael Hebberoy had told him his salary could no longer be met. He is currently the chef at Lovely Hula Hands in North Portland.) Naomi Hebberoy would stay on salary at Clarklewis, as general manager, a gig Howitt says she eventually proved unsuited for.

Word spread instantaneously through the food community and in the local media: The Ripe empire had fallen. The prince and princess of Portland’s culinary scene were in the midst of a divorce. Former employees and food bloggers variously glorified and vilified Michael Hebberoy, and adulation turned to rumor-mongering: He had purportedly fled to Mexico, with a woman who was or was not a stripper, with or without investors’ money in his pockets, possibly with a book deal, possibly with part ownership in the upcoming "modern bohemian" Ace Hotel. Sightings of Hebberoy funneled in from Los Angeles, San Francisco and British Columbia.

Few, if any, of the investors had seen it coming. "We expected [the business] was being handled, and it wasn’t," says Howitt, adding that to the best of his knowledge, no one had ever asked to see Ripe’s books.

"Michael had done such a fantastic job up until the final day, doing this dance that everything was great," he says. "All I knew was: I came into Clarklewis frequently, and it was jam-packed, and in my mind, if you’re in a restaurant that’s jam-packed with a huge waiting list and it’s won Restaurant of the Year and gets glowing reviews in Gourmet magazine, you assume that the business is good. But what we didn’t know was, when the menu offered white truffles with osso buco for $27, it was actually costing the restaurant $30."

In fact, Michael Hebberoy says he had known for quite a while. "Ripe was in a financial catastrophe every three months," he says. "After the first year, Clarklewis was losing money hand over fist; it never paid the bills for Gotham. They had a net zero balance, back and forth." And yet, through charisma and perseverance and "definitely some juggled money" between the businesses, Michael had been able to Band-Aid Ripe together for a while.

That Naomi Pomeroy (who reassumed her maiden name after the couple separated) had not been privy to how bad Ripe’s finances were may be partly attributed to youthful naïveté (she says, for example, that she "didn’t even read" the lease she signed at the Gotham Building). Mostly, she says, it’s because the business sprouted from Michael’s and her personalities: He was "the big picture guy"; she, "the motherboard. I directed all the flight traffic in and out."

In the early days, the division of labor worked. But as Ripe blossomed, Hebberoy became less interested in food per se and more interested in its uses as a creative force. His new ideas kept coming, even when the former projects had not yet been completed. Such megalomania resulted in "10 times more work for me," says Pomeroy, as well as confusion among the staff.

Moreover, she says she saw how publicity had become a dependency for Hebberoy–and then, a liability. "Michael’s extremely creative, but I think he started to feel like every time we got accolades, it was about him," Pomeroy says. "He couldn’t separate his own identity from the businesses. Every time something bad happened, he was shrunk down and really fearful."

His anguish was not enough to convince her to abandon Ripe or Portland. In January, Pomeroy started throwing Sunday night "suppers" at Clarklewis; she has a new boyfriend; she is still on the payroll at Clarklewis (Howitt calls her "the culture, the PR and the outreach" of the restaurant); and she says the community has been extremely supportive. "I had to stand in front of people saying, ’I’m really sorry, but I’m probably not going to be able to pay you back that gob of money you gave us,’" she says. "And most people said, ‘Hey, 80 percent of restaurants fail; you kids tried your best.’" Her divorce from Hebberoy, who plans to keep that name, was granted in late January.

Still, the fragrance of Ripe, in its headiest days, lingers for her. "I’m 32 now, and have already had so much success," Pomeroy says. "There’s part of me, like after a love affair, that wonders, Am I ever going to be there again?"

There are plenty of others still recovering from the breakup.

Tommy Habetz, now the chef at Meriwether’s in Northwest Portland, says he saw the romance go south as soon as he partnered with the Hebberoys in Gotham Building Tavern. GBT was a disaster from the beginning, says Habetz. The build-out, which Michael Hebberoy oversaw, took too long and cost too much; and the plan that Habetz and Naomi Hebberoy would be co-chefs was a "bad idea from the start." And while Habetz continued to receive superb reviews for his food, he watched as his efforts were lost in the reams of press Michael created around himself as a food pioneer.

"He would focus on this pie-in-the-sky stuff rather than what’s at hand," he says.

By design or accident, says Habetz, Michael Hebberoy was beginning to burn his own bridges with the press and the public. He famously dissed Alice Waters–owner of Chez Panisse–in the pages of Food & Wine by saying, "People say that [she] launched a food revolution, but they’re wrong. That was only an ingredients shift." And in July 2005, after Michael tried to line up buyers for his yet-to-be produced GBT gin on a trip in New York, the Oregonian’s A&E section published snippets of his diary (although Michael claims he never gave them permission to print it): "I have squeezed every little last drop of my essence onto their conference tables–and they loved it. The moral of this story … New York will have us … anytime we like."

"These statements were just ridiculous," says Habetz. "I was like, It’s bullshit, and it’s going to make everybody hate you."

Whether everybody did grow to hate him or people were simply confused by the tavern’s ever-changing menu and hours–not to mention the exclusive wooden "pods," which diners could pay a $50 premium to sit in–customers weren’t coming in, and the tavern was hemorrhaging money.

Habetz eventually confronted Michael Hebberoy. "And he just blew up," Habetz says. "He’s like, You’re either with me or against me. I was really trying to be a friend to him. But look at someone like Mario [Batali]; who’s Mario’s close friend? Michael Stipe? He doesn’t really have close friends; people talk shit about him. That’s the price of fame."

Habetz has moved on to a more stable restaurant relationship, but Brownlow, after struggling for months to cook his way at Clarklewis under new economic strictures, left in December and has yet to find another kitchen to call home.

"I’m still not sure what to do with myself," says Brownlow, who compares the experience of building and then leaving Clarklewis to "getting married and divorced and losing a child all at the same time."

"We worked really tight together. Michael had a clear vision as far as architecture. Everything in the kitchen, I did. We hit the ground at 100 miles an hour."

When asked whether he felt like a rock star, Brownlow says, "Sure. Why not?"

His stardom ended, however, the day Michael split town, an event Brownlow says he also did not see coming. "It was chicken shit," says Brownlow. "It was very weak."

"When I opened the place, I told everybody I wanted to be around for 20 years or more," he says. "I wanted it to be the Chez Panisse of Oregon."

It lasted, for him, for only two.

David Howitt sounds entirely sincere when he says he does not care whether Clarklewis makes money; "it just can’t lose money," which he says would have been the case had Brownlow stayed and continued to incur exorbitant food costs. He sounds equally sincere when he says it’s important to the city that Clarklewis succeed.

"In any other city, if someone screws you out of your investment, you’re never walking into that door again," says Howitt. "Or worse, you might be maligning it, and saying, Don’t eat there; they’re frickin’ losers; they stole our money! Here, I come in and look around the room and say, Oh, there’s an investor that comes here once a week, and he lost 50 grand here. And he’s in having dinner. That is Portland, right? Through all the drama, people still come here and eat."

Not everyone is as charitable. "I don’t think Clarklewis is going to last the first quarter of 2007," says one chef, on condition of anonymity. Another calls Michael "Little Lord Hebberoy," and says that he and Pomeroy were so spoiled, "they used to call their landlord at Gotham and ask him to change the toilet paper."

"A lot of people in Portland grumble about them leapfrogging the chain of servitude that we in the kitchen all feel like you need to go through," says Leather Storrs, who was the chef at Noble Rot when it was named Restaurant of the Year by Willamette Week in 2003 just before Clarklewis opened (Storrs is currently chef and owner of soon-to-open Rocket restaurant). "Mario Batali was the one who said, ‘We bring in food, we fancy it up, and we sell it at a profit. And don’t delude yourself into thinking we do anything else, because when you do, that’s when the problems start.’"

Still, Storrs is tickled by what Michael Hebberoy tried to pull off. "This Svengali weaves his magic web and seduces everyone, then steals out under the cover of darkness. Then, he’s gone to the evil sister city of Seattle to do it again! It’s beautiful! You want to sit back and just applaud."

In September 2006, five months after Family Supper and Gotham’s doors closed, Michael Hebberoy wrote a short article about "fall’s best new restaurants" for Men.style.com, in which he is identified as a "Portland-based chef [and] architect."

Today, he is neither of these. Hebberoy currently lives in Seattle, in a sparsely furnished house he rents in the Madrona neighborhood with a childhood friend. From the dining room’s bay window, he enjoys a lovely view across Lake Washington.

On a Sunday afternoon in mid-December, the house smells of chicken broth, which Hebberoy is preparing for his new "event"–called One Pot, in which the main course is, as may be self-evident, all cooked in a single pot–which he will host this evening with a guest chef at Verité Coffee, a café and cupcake shop, also in Madrona. The invitation, written all in lowercase letters and sent via e-mail, began: "one pot is meant to be a bit more than a way of cooking, or a way to gather people, or a way to make some cash. it is meant as a gesture–a gentle fuck you–to the corporate box we reside in and are supposed to dine in." Those who warmed to the entreaty received a confirmation that included instructions to bring $35 cash.

"Me moving to Seattle, Jesus Christ," says Hebberoy, looking younger than 30 in a too-small, soft T-shirt and moppety hair. "Every top person in the field of art and culture in this town has been tapping my shoulder about One Pot." He cites cultural lightning rods as disparate as "the Al Gores" and "the coolest punk clubs."

"I don’t have to deal with bridge-and-tunnel and money guys and financial guys; I get to deal with creative folks these days, and that’s always what I wanted to do," he says. "Portland and I broke up."

An hour before he drives the broth to the evening’s event, Hebberoy turns to the topic of the people he left behind in Portland: the Howitts are "striped-shirt idiots"; the Oregonian A&E article that quoted his diary is "one of the most stupidly written pieces ever"; and Pomeroy and Habetz are to blame for Gotham’s demise. His only kind words are reserved for Brad Malsin ("I love Brad") and Morgan Brownlow, although the latter olive branch was extended, according to Hebberoy, only after Brownlow sent an e-mail apologizing for saying anything negative about him. In response, Hebberoy invited Brownlow to Seattle to cook at some One Pot events. Brownlow initially refused, but in late January, asserting that "life’s too short to contemplate one’s failures," he accepted the invitation.

The conversation turns toward the days leading up to Ripe’s demise. Hebberoy says that he was "terrified," and that he desperately tried to keep the company afloat by telling bigger and bigger stories, about hotel projects and their house gin and books that didn’t yet exist–the "build it and they will come" model in reverse.

"The only avenue I saw was getting people excited about the vision of its future as a brand," he says. "Because as an entity in and of itself, its profits and losses sucked. I was selling blue sky, because that was the only thing I knew how to do."

The crowd at the evening’s One Pot, about 40 people, most in their 30s with expensively shagged haircuts and architectural eyeglasses, certainly seems receptive, sharing the bottles of wine they’ve brought and sitting at candlelit tables. Hebberoy taps his glass and welcomes everyone by saying, "There are no rules," and then reads a lengthy passage from The Supper of the Lamb, a 320-page rumination on the preparation of one dish by Robert Farrar Capon.

"Huh, now I know how to cut an onion," says one diner, a designer for Starbucks, who enjoys two helpings of faro salad with caramelized onion but doesn’t touch most of the evening’s "one pot" item of pork roast.

People fall into easy conversation, and all seem to agree: It’s an unusual way to spend a Sunday evening, and really, there is no place else like it in Seattle. And then it’s 10, and there’s a scraping of chairs, and people gather in the doorway. Hebberoy stands among them, talking up later events and new One Pot venues, encouraging people to swap business cards. He seems comfortable in this skin, no unkind words, only warm handshakes and enjoinders to come again.

As guests nab complimentary boxes of cupcakes at the door, Hebberoy slips away, toward the evening’s dirty dishes, which still need to be bused.