The Beers of Summer

Image: David Emmite

Portland is the epicenter of craft brewing in the United States, according to Wall Street Journal writer Ken Wells in his 2003 book Travels With Barley. And he’s not the only one who feels that way. In fact, it would take up more space than we have allotted to recount all the honors and accolades that have been poured on Oregon thanks to our homegrown beer industry.

Portland has always been a tavern town that moved a lot of draft, but it wasn’t until the late ’70s that the seeds of the craft-beer revolution took hold. During the hedonistic days of the Carter administration, Sen. Alan Cranston (D-Calif.) introduced a bill that would allow a single person to brew up to 100 gallons of beer annually for personal consumption (200 gallons for larger households). The bill passed and homebrewing went public, graduating from the bathtubs and medical tubing of Prohibition-style basement operations or the beakers and pipettes of dorm-room setups to the carboys and hydrometers of a legitimate cottage industry.

Around these parts, winemakers like Dick Ponzi and Chuck Coury were eager to get into the game, and homebrewers, like the Oregon Brew Crew, were already good to go, having been weaned on local writer Fred Eckhardt’s A Treatise on Lager Beer (1969). "Fred’s been around the whole time," says Brian Butenschoen, executive director of the Oregon Brewers Guild. "And everybody who started brewing in the breweries, from Karl Ockert (Bridgeport Brewing) to the Widmers to Fred Bowman and Art Larrance (Portland Brewing), they all had that homebrewing experience."

Mike and Brian McMenamin are credited with the state’s first true brewpub, the Hillsdale Brewery & Public House, which opened in 1985 after the state Legislature passed what came to be known as the "brewpub law," making it legal for brewers to sell directly to the public. But the young entrepreneurs took some heat when the established beer distributors dug in their heels and fought the encroachment onto their turf by any means necessary.

"As we made inroads, some of the distributors did their best to thrash us," says Kurt Widmer. "They talked about how our sanitation conditions were less than optimal. Our brewery at the time was a little bit dark and dour, but we did a great job of keeping everything clean. The piping, the hoses and the tanks, everything the beer touched we kept spotless."

Fortunately, stalwart publicans like Don Younger at the Horse Brass, Carl Simpson at the Dublin Pub and Bill McCormick at Jake’s went to bat for the rookies and helped them get a foothold. "And all the distributors’ nightmares came true," laughs Bridgeport brewmaster Karl Ockert.

So we have a confluence of beer geeks, nervy tavern owners, timely legislation and a populace with taste buds attuned to more complex beer than, uh, Bud. Anything else?

Ingredients.

We’re the No. 2 producer of hops in the country, with Yakima Valley in Washington holding a commanding lead. We also rank a healthy No. 9 on the barley list. Great Western Malting is just across the river in Vancouver, and Wyeast in Odell, outside Hood River, is one of only a small number of yeast cultivators in the United States. "And we have mountain-fresh water," notes Jerry Fechter, co-owner of New Old Lompoc. "Just like the big guys."

And let’s not forget the weather, Eckhardt adds. "During the winter there’s nothing else to do but sit inside and drink beer."

Fortunately, summer’s upon us and it’s about beer-thirty, high time to acknowledge those local beers worthy of a second round. Here we present the Summer Beer All-Star team, a dozen profiles of brewers, publicans and the beers that made them famous. Our hoppy homage is by no means scientific or definitive, and we welcome additional input. Hopeful brewers are encouraged to lug samples over to the Portland Monthly office. Disclaimer: This team is for summer beers. Stouts and porters need not apply. Until November.

{page break}

Turk’s Head ESB

The Alameda Brewhouse, a Northeast hop spot that features agreeable edibles and décor that drapes steely modern flash over its blue-collar torso, turns 10 this summer. Brewmaster John Eaton, who’s been tending the tanks for the last four years, touts all the selections brewed on the premises: Black Bear XX Stout is an award-winner, and the Klickitat Pale Ale is the top seller. The brewhouse also pours Siskiyou Golden Ale, a popular entry that’s earned the evocative moniker “lawnmower beer” for its hot-weather drinkability.

But the Turk’s Head ESB is the most robust and distinctive brew here, leading off with plenty of hops and cleaning up nicely with a dry finish and a lingering caramel roasted malt aftertaste. And it favors finesse over power.

“It’s a real English-style ESB (extra special bitter),” Eaton explains. “And it’s pretty low on alcohol, only about 5 percent. The idea is that it’s still full-bodied and has a lot of crisp bitterness to it—and you can make it a session beer.”

In other words, you won’t need to call in a lightweight as your relief pitcher.

“At a lot of breweries, their best beer is like 8 percent alcohol, which is fine, interesting and good,” he continues. “But we’re not talking about a beer that people can sit down and have a couple of and feel OK. English beers are a little lower in alcohol and a little more subtle. But Turk’s Head still has a lot of hop bite and malt backbone. It should be smooth and crisp and leave you with something.”

Besides a hangover, that is. Just because the Bambino and Mickey Mantle had the intestinal fortitude to play through the previous night’s chug-a-lug doesn’t mean you have to attempt it yourself.

Supris

Bridgeport Brewing, among the most guzzled of the veterans on this squad (established in 1984), is currently ranked No. 41 among the top 50 American breweries in production. Brewmaster Karl Ockert is the company’s revered elder statesman; aside from a five-year “professional odyssey” in the early ’90s when he ventured forth to start some pubs in Washington and serve a stint in the majors with Anheuser-Busch, Ockert has been the brains behind Bridgeport’s brew. And the venerable ivy-festooned pub on NW Marshall St—recently renovated to include a bakery in its more brightly polished interior —is still teeming with fans of his ageless ale artistry.

“I tell people that when Dick Ponzi and I were first building this place, we didn’t know if we were going to be in business for three months or 30 years,” Ockert says. “And luckily, it’s been closer to the 30-year mark.”

For the last decade, Bridgeport IPA has been a Northwest all-star, successfully steering palates away from watery domestic lagers and viscous stouts toward lighter, hoppier pleasures. In part thanks to Bridgeport’s consistent firkin excellence, IPA has become the pad Thai of the local brewpub menu.

“It’s pretty much been the gold standard of IPA,” says Laurelwood’s Mike De Kalb, while John Eaton, the brewmaster from Alameda Brewhouse, cites Bridgeport IPA as possibly his favorite bottled beer.

“Our IPA has gone from being a niche beer that we were going to brew every once in a while, because it was so hoppy, into being a leader in that category,” Ockert enthuses.

But there’s a rookie from foreign soil in the Bridgeport clubhouse that’s been turning heads of late. Supris (soo-prees) is a yeasty blonde seasonal offering with a jolt of spice and fruit, making it a top prospect on the summer beer circuit. Ockert is pleased with the newcomer’s performance, but concedes its emergence posed a challenge.

“It’s a bold departure for us because we’ve been all about Northwest ingredients, which is typified in the IPA,” he says. “The Supris is German barley, German malt and German hops, Czech hops and Slovenian hops, and then we use this Belgian yeast that gives it a very yeast-driven, spicy clove flavor. It’s a difficult beer for us to make, because we have to rely on foreign ingredients, but it’s really worth it.”

It certainly accords with beer fanatics’ immigration policy: Give us your yeasts, your malts and your Slovenian hops—yearning to be beer.

{page break}

Session Lager

Welcome back, little guy. After Olympia Brewing’s beloved stubby bottles disappeared off the shelves for good in 2003, Full Sail Brewing recognized an opportunity—and leapt at the chance to fill a precious void in the consciousness of Northwest beer lovers with the advent of its Session Lager.

“We had talked about doing a stubby bottle ever since we’d heard Olympia was going to close,” says Full Sail’s executive brewer Jamie Emmerson. “We talked about it because of the following, and because of that nostalgic view.”

But there’s more to the story than a beer company getting style points for going the retro route. Full Sail Brewing has been employee-owned since 1999, but as one of the state’s major beer producers (No. 26 among American breweries), the player-managers on staff seldom make a decision based purely on sentimental reasons. Emmerson said Full Sail was looking to win fans of more conventional beer who seemed to be having trouble wrapping their taste buds around Full Sail Amber, Rip Curl and other bold brand titles.

“I had a crew of construction workers working on my house,” Emmerson says. “And I brought some Full Sail beer out for them, you know, ‘free beer, free beer.’ And they said, ‘No thanks.’ I just figured they were on the wagon. So next week I came out and they were drinking a fine Mexican beer. So I said, ‘Hey, how about some Full Sail?’ And they said, ‘No, no; it’s too bitter, too heavy.’

“Stylistically we found they’re buying the beer, Heineken, Corona, etc. And they’re paying the price, because none of those beers are inexpensive by any means. But they’re not picking us because of the taste.”

Session may sound like a concession to the plebeian palates of beer’s rookie leagues, yet Emmerson and his cohorts brought considerable research, toil and trial-and-error to the plate, and the results have been solid. Session has proved a brisk mover amongst the Pabst Blue Ribbon (still the most popular beer in town) crowd, and it recently claimed a bronze medal at the World Beer Cup.

And Full Sail certainly deserves props for developing a tasty, modestly priced lager that comes in a familiar—and comforting—shape. “If we had put an ale in the stubby bottle, a Full Sail style beer, I think there would have been a disconnect between the bottle shape and the taste people would expect,” Emmerson says.

Ruth American Ale

Situated in a former iron foundry among a warren of industrial outposts near SE Holgate Blvd, Hair of the Dog Brewing and its “top dog” Alan Sprints conduct their beer business with a humid élan. Reggae thumps through the tidy brewery while employees amble about in shorts and flip-flops. In one corner there’s a small bar rigged with a half-dozen taps: This is the tasting “room.”

There’s no question that Hair of the Dog is one of the most respected and innovative breweries in Portland (established in 1993), if not the entire Northwest. But the summer beer formula—light and invigorating, prompting the consumer to consume a bit more freely—is not normally associated with this lot, whose mystique is more Bad News Bears than Yankee pinstripes. Hair of the Dog’s noggin-knocking offerings include Adam, a dark “dessert beer” that weighs in at a hefty 10 percent alcohol, and the “special golden” Fred (named after beer writer and historian Fred Eckhardt—), another 10 percent monster.

“My beers are big and strong; they’re not the kind of beers you have four or five of, so I found it difficult to sell much volume here in Portland,” the affable Sprints says. “And I wanted to do something to help that.” Ladies and gentleman, meet Ruth.

On first taste, she delivers a provocative dose of Crystal hops, but it’s not overly bitter and gets progressively less assertive and more palate-friendly over the duration of the bottle (sorry, it’s not available on draft—browse your local upscale grocery store).

“I always tell people Ruth is more or less like a regular beer,” Sprints says. “You won’t be too surprised when you try it.” Sprints names most of his beers after those near and dear to him; Ruth is his mother’s mother. “It’s my attempt at a lighter beer,” he says. “Granny doesn’t really drink beer, but if she did, she’d definitely drink Ruth.”

{page break}

Organic Free Range Red

One could be forgiven for expecting bush-league beer when visiting the Laurelwood Public House. Despite the hulking presence of the brewing tanks,

its well-scrubbed, family-friendly interior (a play area? Sacrilege!), bountiful menu of pub grub and display case of diet-unfriendly desserts somehow suggest that worthy beer may not be available in this clubhouse. That notion is quickly dispelled by the line-drive arrival of the brewery sampler of eight beers (3 oz each, $8) or simply by getting cozy with the Organic Free Range Red, the top pitcher in the house. It’s a bold brew in the prime of its career, known for a full-bodied, expansive taste and numerous ardent admirers among the local suds set. Owner Mike De Kalb says his Boss IPA is the best-selling beer in the pub itself, but Red is the most widely distributed, to between 50 and 60 accounts in town. And friends of the earth can drink deep—it’s organic.

“Free Range Red won the gold medal at the World Beer Cup in 2004 for the best ESB-style beer in the world,” De Kalb says. “It didn’t matter that it was organic. It was just the best ESB. Whenever we enter these competitions, we never enter our beers in any organic categories. We just enter them in the regular categories.”

De Kalb’s zeal for ale and knack for fashioning an “everyone is welcome” vibe is paying big dividends in development. The company has two locations, with a third on the way. De Kalb plans to move the restaurant part of the operation a few blocks down and leave the current location off NE Sandy Blvd to serve as brew HQ. “We’ve totally outgrown this brewery,” he says. “The demand has been amazing.”

De Kalb is quick to praise the contributions of departing brewmaster Christian Ettinger, but he’s got his eye on the next ace warming up in the bullpen.

“Chad Kennedy is our new brewmaster, and he’s been with us for 3½ years,” says De Kalb. “I think eventually he’ll show us some real innovation and creativity.”

The scouts are watching, kid. Better bring your best stuff.

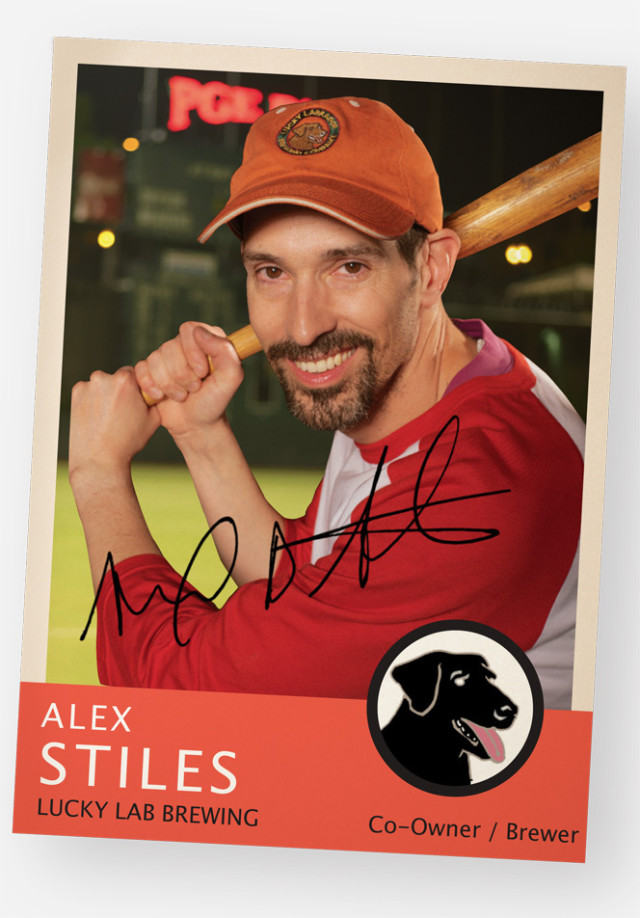

Superdog

Known primarily as that place on SE Hawthorne Blvd where thirsty dog owners can paws for a bit of refreshment while their canines carouse out back, the Lucky Lab has bulked up to three locations—a second in Multnomah Village and a third recently opened in Northwest—thanks to unpretentious chow, a shorts-and-caps warehouse ambience and a roster of beers that range from complex to comforting.

Alex Stiles, who served his apprenticeship as a Bridgeport brewer in the early ’90s, has been part of the ownership contingent since the Hawthorne pub opened in 1995, and along with Dave Fleming is a key architect of the Lucky Lab beer arsenal. According to Stiles, the telltale mark of a good brewer is the ability to turn a near error into a heads-up play. “We have a few beers on our menu that were total screw-ups by the brewer—usually me, or my old assistant, who’s long gone,” Stiles says. “Like Superdog. It was a mistake, and it gave us an opportunity to really hop it up.”

Fleming’s recollection of the birth of Lucky Lab’s nascent dog star differs somewhat. “Alex went to New Zealand and left the rest of us knuckleheads in charge—that’s what happened,” he recalls sheepishly.

“I was training this guy and he added too much grain to our Top Dog, so I said, ‘Well, it isn’t Top Dog anymore. It’s Superdog!’ So we super-dry-hopped it (added more hops after the original boil to increase the bitterness). It was kind of over-the-top on the hoppiness scale at the time, but people loved it. Now everyone’s got a superhoppy beer.”

Thanks to Bridgeport raising the IPA profile, reports from most pubs in the area indicate that variety as the top-selling style—which was formerly the case at Lucky Lab. But the race for No. 1 has tightened up considerably with the arrival of a certain hoppy hound: Superdog and Dog Day IPA are dead even in sales.

“Portland is a bunch of hopheads, and Superdog is nice and bitter for them. But it’s the aromatics that draw them in first,” Stiles says. “Everyone smells the beer first—and it smells good! It smells green and spicy.”

“Dry-hopping gives it that flowery nose, but it’s super bitter on the back end,” Fleming adds. “It’s a nice contrast.”

And a lucky catch saves the day.

{page break}

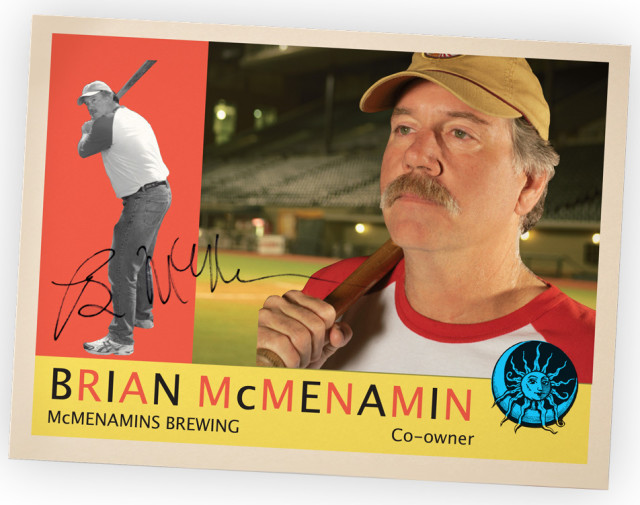

Ruby

Mike and Brian McMenamin have traveled quite a distance since their formative years tending bar at Produce Row in the 1970s. Part of the contingent that pitched the state Legislature on the idea of brewers selling their beers to the public, the brothers McMenamin have sired pubs, hotels, movie theaters and restaurants, and their appetite for expansion shows no signs of waning.

Currently on tap are plans to move the company offices into the Little Chapel of the Chimes on N Killingsworth St and to put in a bar behind bars at a former jail site adjacent to the McMenamins Edgefield spread in Troutdale.

With all the fuss over the company’s entrepreneurial enthusiasm (53 locations in Oregon and Southwest Washington), the beer that put it on the map tends to get overlooked. And while McMenamins’ signature brews bear intimidating handles like Terminator and Hammerhead, it’s the more demurely designated Ruby that’s become a regional summer-beer staple.

“It started with a patch of blackberries in the parking lot,” Mike McMenamin recalls, referring to the Hillsdale Pub, the first of the company’s locations with a brewery on the premises. “We did a test brew to see what would happen—and we found there were some possibilities. Blackberries were first, and when we eventually tried raspberries it became immediately apparent that they were a key component. It was a great berry to work with.”

“And we tried ’em all,” adds head brewer Kevin Tillotson. “But there was something special about raspberries. It’s got a nice tartness to balance the sweetness from the malt. It’s a nicely balanced beer.”

McMenamin notes that Ruby was among the first 50 batches of beer produced by his fledgling operation—and one that flew in the face of conventional wisdom. There were no other fruit ales on the local front. “A lot of it was a reaction to what you should do, and how you should make beer,” he says, “and just throwing it out the window and saying, ‘Let’s just go nuts here.’”

This coming from a brew gang that once threw candy bars into the kettle, and once cooked up a beer called Afterburner—which had garlic in the mix.

“Ruby was a reaction against classic stuff,” McMenamin says. “But it definitely became kind of a classic.”

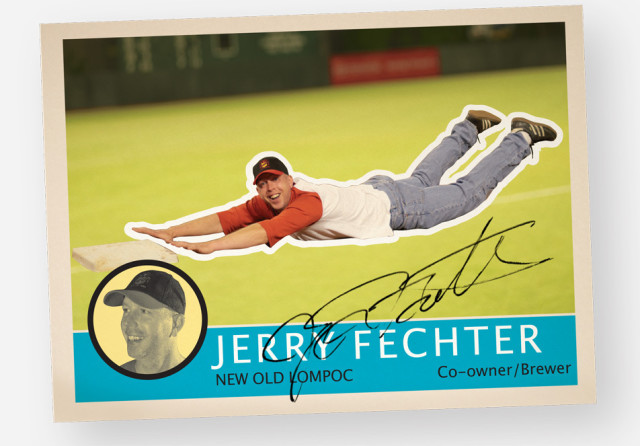

C-Note Imperial IPA

The New Old Lompoc brewing franchise—three picturesque pubs and counting—is responsible for one of the heaviest hitters in the summer beer lineup, especially from a hops standpoint. Brewer and co-owner Jerry Fechter invented C-Note to impress other local brewheads at the behest of Horse Brass publican (and NOL’s co-owner) Don Younger in honor of the Horse Brass 25th anniversary party a few years back.

Fechter was instructed to come up with a “really big beer,” so he decided to go hell-bent for hops—and get conceptual with the alphabet at the same time.

“Scientifically, I don’t think you can brew a beer over 60 or 70 IBU (international bittering units, a measure of a beer’s bitterness from the addition of hops). But on paper you can really get it up there,” Fechter says. “If you have a crazy boil then you can extract a lot more bitterness from the hops. I wanted to get one over 100 IBUs. So we ended up using 18 or 19 pounds of hops in a six-barrel batch. I think on paper it came in at like 108 IBUs.

“And I just thought it would be neat to make a beer with all the hops that start with the letter ‘c’: Cascade, Columbus, Centennial, Crystal, Challenger and Chinook.”

Hence the name C-Note, an IPA that’s out of the park in terms of hoppiness, but by no means a one-dimensional player. It has plenty of malt body to back up the bite and dries off nicely, leaving the mouth clean as a freshly swept home plate, eagerly awaiting the next delivery.

“That’s the art form,” explains Fechter’s partner Don Younger. “One hundred IBUs should rip your throat a new one; it would be like drinking battery acid—unless you can find a way to balance it.”

Like most of his brewing brethren, Fechter views local competition as friendly for the most part. He praises the work of other brewers and views the prevalence of pubs in Portland as nonthreatening, likening the scene to the culture in England, with each community having a local to call its own.

“Every little neighborhood is slowly getting its own neat little brewpub,” he says. “Maybe in the ’60s and ’70s they might have been smoke-filled taverns filled with blue-collar characters, but now we have pubs with good food, no smoking and friendly toward families—and with really good beer.”

Take me out to the brewpub / Take me out to the crowd / Buy me some C-Note and Cracker Jack …

{page break}

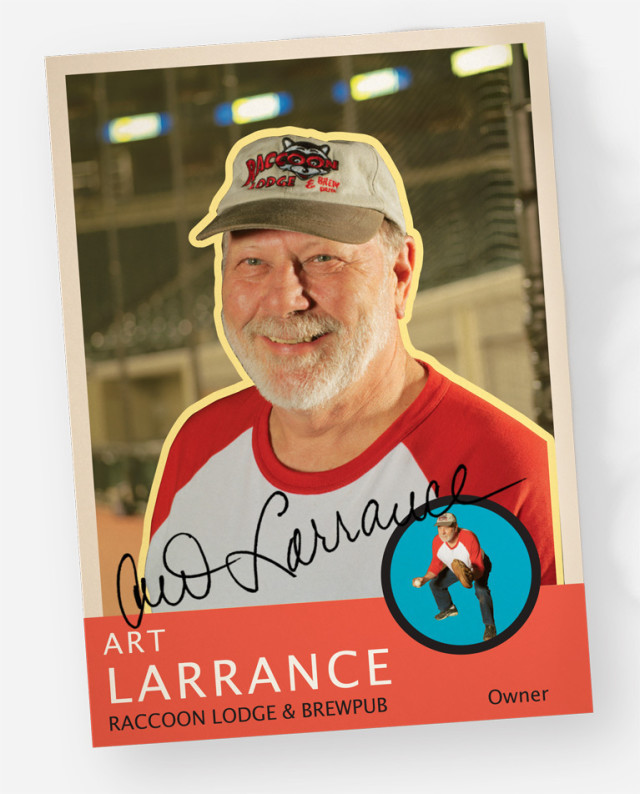

Blonde Bock

Going, going … gone! The hopheads are outta here! A visiting team from Portland proper might feel a tad lost at this Raleigh Hills venue, because Lodge owner Art Larrance and his “chief imagineer” Ron Gansberg brew things a little differently just over the fence in the ’burbs, eschewing the bold bite of hops for Old World balance and palatability. Raccoon beers make an immediate impression as tasty, light and drinkable, but not particularly big or potent. Undercurrents of honey and herbs have a pleasingly vague presence.

Gansberg, who worked at Bridgeport for eight years and Portland Brewing for another three before joining forces with Larrance 10 years ago, is particularly pleased with the Blonde Bock, a beer that combines the lightness of a lager with the sturdier qualities of Belgian-style ales. It’s spicy, crisp and dry, isn’t overwhelmingly hoppy and makes for an excellent change-up from the IPA wave.

“I know what people like to drink around here,” Larrance explains.

“I didn’t really want to make a big, cloying, sweet beer,” adds Gansberg. “I work very hard to balance the hops and the malt. But we are in a hops arms race, there’s no doubt about that.” Indeed, the Lodge’s top-selling beer is an IPA.

Larrance is a highly significant figure in the beer scene: He brewed for Bert Grant in 1983, founded Portland Brewing in 1986 with Hillsboro High School classmates Fred Bowman and Jim Goodwin (Glass of ’62) and started the Oregon Brewers Festival in 1987.

“But I’m not really on the brewing side of things,” he says. “I’m more on the drinking side.

“I knew what kind of place I wanted,” Larrance says of the Raccoon Lodge, which opened its doors in 1996. “We have a McMenamins down around the corner … and we have a McCormick’s Fish House down the street. So physically I’m between two different levels of service. I’m financially in between, and I’m quality-of-food in between—and in beer I think I’m above all of them.

“But that’s in the eyes of the beer-holder,” he laughs. “And I’ve got one in my hand.”

Burghead Heather Ale

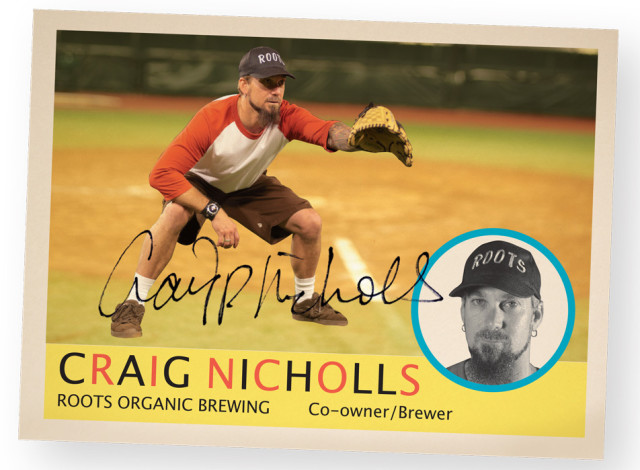

Craig Nicholls is one brewer who doesn’t seem to be capable of sitting still. He started out at Rogue Brewing in Newport, interned at Bridgeport, worked at Big Horn Brewing in Lake Oswego and signed on as the original brewmaster at Alameda Brewhouse in 1996, where he created its signature beers.

But when the brewery he was working for a few years ago was sold, he knew it was time to settle down. “When we opened Roots, we wanted to be creative and totally different—and be the first all-organic brewery in Portland.”

He’s fiercely committed to the principles of organic brewing (no pesticides or chemicals added to his raw ingredients), though he estimates it costs him between 35 and 40 percent more to import his hops and grain from Europe.

“Everything we do here is organic,” he says of the tropical-themed brewpub that he opened last year with business partner Jason McAdam. “The whole place is built out of recycled materials for the most part. Everything except the drywall.”

Apparently the organic bug is contagious. Nicholls says that Roots services close to 100 accounts around the state and that “two or three” local breweries set to open in the next two years will also be organic.

Roots also is the home of the Summer Beer All-Star team’s ideal relief pitcher, Burghead Heather Ale, an offbeat brew that throws hop-accustomed palates a mean curve ball. With its complete absence of hops, Burghead gets a substantial zing from heather—and from history.

“The story goes that archaeologists found these old Gaelic tablets at a dig site,” Nicholls says, estimating the recipe at 3,000 years old. “They knew it was a beer, but they didn’t know what kind.” Upon first taste, Burghead settles in the mouth like a fruit beer, but it’s light and crisp with a refreshing floral taste.

“The heather adds a nice dry finish but without the cloying, acidic taste that you get from hops,” says Nicholls. “It’s a great beer, one of my favorites.”

{page break}

Hefeweizen

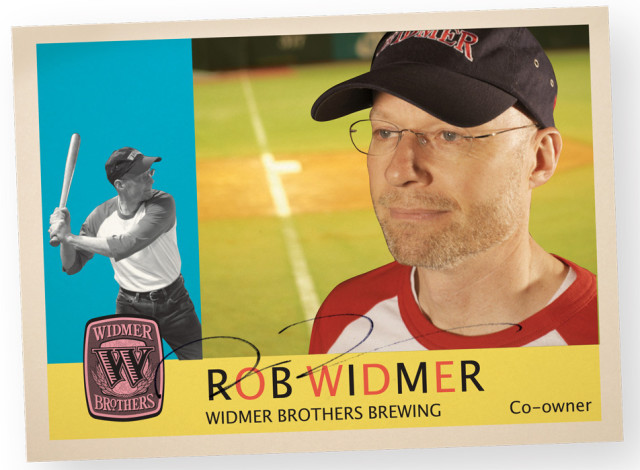

The Babe Ruth in this lineup of titans is Widmer Hefeweizen (hay-fuh-vie-tzen). It’s the most recognizable beer in town, the fan favorite, a perennial slugger standing tall above the crowd, even as younger, flashier names try to coax the spotlight in their direction. And with more taps in Portland dedicated to Hefeweizen than to Budweiser, Widmer Brothers stands at a lofty No. 17 in beer production among the top 50 American breweries.

But the origin of the cloudy conqueror with the lemon perched fetchingly on the rim wasn’t exactly auspicious. Kurt and Rob Widmer entered the game in 1984 after getting bitten by the homebrewing bug five years earlier. Their inaugural effort, Alt, was a hoppy ale that debuted some 10 years before locals went loco for IPA.

“We had like 10 very enthusiastic beer drinkers, and the rest stopped at one glass,” Kurt Widmer says. “So we realized pretty quickly we needed to dial it back a little bit if we wanted to attract a broader audience.” Time for a little creative brewing.

“We had a request from one of our accounts (Carl Simpson at Dublin Pub),” he continues. “He had our Alt and Weizen on tap and he wanted a third beer—and we only had two fermenting tanks. So we just took our Weizen straight out of the fermenter and put it in a keg. And it was only supposed to be for him. But he really pushed it.”

Apparently the allure of the odd-looking and surprisingly mild beer was irresistible. Soon the unfiltered throw-in brew was the young company’s star attraction. Its domination of the local market prompted Anheuser-Busch to buy a minority share of the operation in 1997, adding substantial distribution muscle.

Unlike most beer barons, the Widmers have a farm team. The brothers are former members of the Oregon Brew Crew, one of the oldest homebrewing clubs in the country. And they keep up the connection with the Collaborator Project, which gives Brew Crew brewers a chance to test their mettle before a wider audience.

“We’ll put the best beer recipe on tap at the Gasthaus,” says Rob Widmer. “That’s where Snow Plow, our seasonal stout, came from.”

And with hard work, determination and expertly blended hops and malt comes a shot at the big leagues.

Humulus Maximus IPA

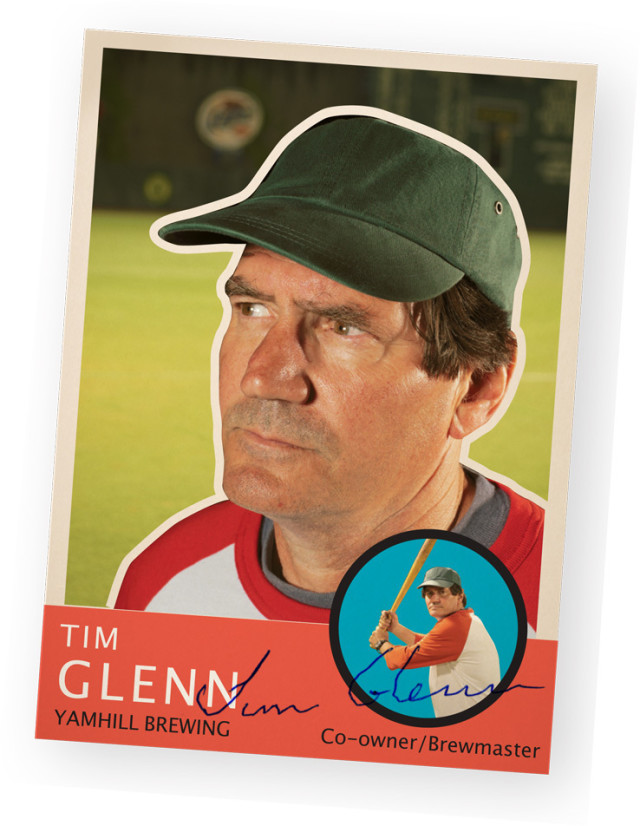

If you’re looking for a little atmosphere with your beer, the Ninth Avenue Public House, the home turf of Yamhill Brewing, probably won’t be high on the list. While other brewpubs make a point of catering to families with hearty portions of comfort food, Ninth Avenue’s menu is a work in progress. True, there might be a band rocking the warehouse area, and recently there was a sketchy fortune teller (her tarot cards had the divine meanings already printed on them) holding court in the back of the room. But as for strategically placed fripperies, it’s all pretty spartan. To be fair, the place has only been open to the public since last November, so maybe the ferns have yet to sprout.

Tucked away among warehouses and auto-body shops in inner Southeast, Ninth Avenue Pub is a place for folks focused on superior suds. Brewmaster and co-owner Tim Glenn came over from Tugboat Brewing about 10 years ago and has been assembling his gear and trying—in fits and starts—to secure the financing to launch the pub side of the operation ever since. A 25-year veteran of the local brewing game, Glenn is a laconic fellow, more at home tinkering among his tanks than out front glad-handing the customers—unless the subject is beer, in which case his knowledge is as deep as a grain silo. Like Dr. Frankenstein periodically emerging from his lab, Glenn can be seen restlessly pacing the premises with a glass half full of his latest concoction, trying to divine its malty merits.

His most magnificent creation thus far is Humulus Maximus, a vivacious IPA that bursts like fireworks with each successive sip, making it an ideal leadoff hitter. It’s light and well balanced, but sturdy, with a majestic wave of hops that doesn’t override the malt. It’s easily one of the finest examples of an IPA in the city.

“Humulus is hops,” Glenn says simply of the beer’s moniker, which refers to the Latin Humulus lupulus.

Glenn observes Portland’s hoppy hegemony as a practical part of his new business, but he has bigger plans in the tank. “It’s something someone needs to survive in the local market,” he says of the IPA. “We might do something even hoppier in the near future.

“But a beer needs to have aroma, body, flavor, color and balance—anybody can overhop a beer and call it good.”

But not good enough to make this team.