To Protect and Serve

RETIRED POLICE OFFICER HENRY GROEPPER can still recall the smell of the methamphetamine he believes gave him cancer, a blend of cat urine and fiberglass—like an old litterbox in a new boat. On one bust in particular, he remembers a stench so searing, the accompanying DEA agent warned him away on fears of an explosion. Even the firefighters were scared. They set up four-foot fans in the doorways, blowing vapors into the street.

“Now,” says Groepper, 25 years later, “I don’t think there’s anyone in this world that would argue the dangers of meth labs.” But back then, the command staff chided cops who worried about the fumes as “complainers.” Besides, reporters were standing by, cameras in hand. And as spokesman for the Portland Police Bureau, Groepper (pronounced “gripper”) had to give them the best show possible. News junkies were like any other kind of addict, he knew: keep ’em fixed, and you keep ’em out of trouble. Stories about busted drug labs—cops doing their jobs well—were a balm on a department that more often earned headlines for its scandals.

So at the hulking house near Mount Tabor, Groepper felt his way into the dark recesses of the basement, one lucky TV cameraman in tow. Battery-powered lights only. No flashes, nothing that sparks. As he watched the camera pan across the monstrous array of steaming glass and potions, he felt a familiar sting in his eyes and nose and, then, a tickle at the back of his throat. Groepper had been in hundreds of these places. Sometimes he thought he could feel his skin crawling, the hair on his body stiffening as if shellacked. Pains crept into his head, his stomach, followed by chills and a tightness in his chest.

Hours later, when the anxious photographer called to say he was sick, Groepper told him the same thing he had been told: There was nothing to worry about. The Portland Police Bureau had looked into it. And while sometimes people felt sick after being in the labs, they always got better.

Groepper was 45 the day he was shaving and spotted a lump on the right side of his neck. Soon after, a doctor told him he had non-Hodgkins lymphoma and the “lungs of a 70-year-old farmer,” meth fumes being as toxic as pesticides. Seeking a second opinion, he saw an oncologist at Oregon Health & Science University, who put his feet on a desk, leaned back in his chair, and casually gave him five years to live.

A northeast Portland meth lab in 1985, destroyed by a chemical fire.

Archive ID 8000-03, 1985

Image: City of Portland Archives

“It’s hard when somebody tells you that,” said Groepper, whose children were age 16 and 19 when his condition was diagnosed. “That’s not a lot of time.”

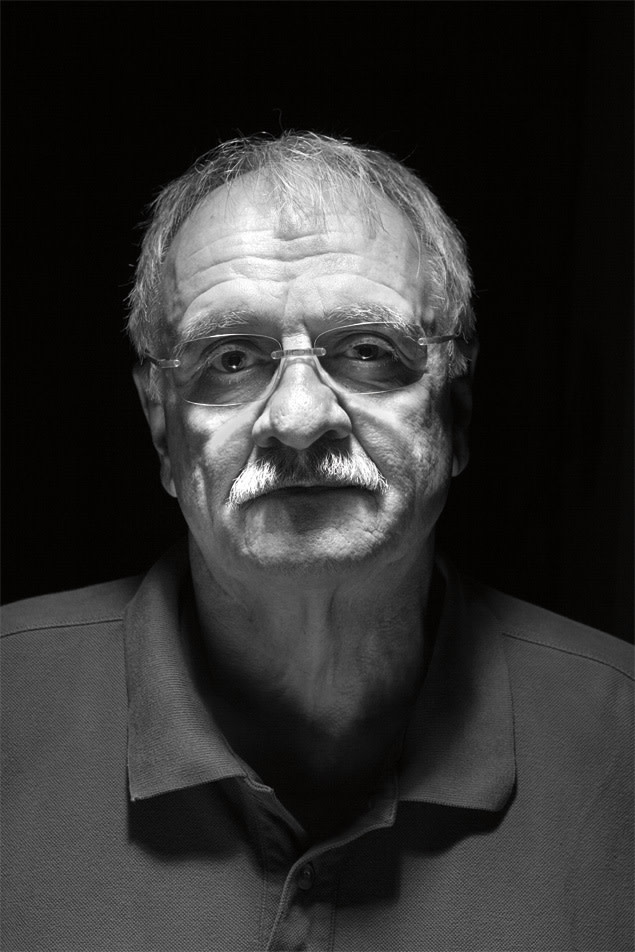

Today, AIDS research has extended the lives of people with immune-system diseases like non-Hodgkins lymphoma, Groepper’s included. He retired from the police bureau in 2005 at 61, but he’s still all cop inside, and a little bit out. He’s chair of the board of Crime Stoppers of Oregon, which solicits tips from the public to help investigations. He also records a public service segment on KXL called “Cold Case,” airing files on unsolved murders, sometimes dozens of years dormant. Over the past two decades, Groepper’s health has had upticks and nosedives, but his presently warm complexion and robust personality conceal that his cancer is creeping back.

And yet, Groepper is one of the lucky ones. Sort of. He at least got some of the benefits he says the City of Portland promised him. The city has paid for his cancer treatments while he foots the bill for all other health coverage. Many of his colleagues haven’t fared so well. Disabled, like him, during their public service, 104 have no city-paid health benefits at all, despite promises from the city that they would. Another five receive only limited coverage.

Groepper opens every Cold Case spot with a simple motto: “We don’t give up. We never give up.” Likewise with the case of the missing benefits. After six long years of sleuthing in dusty archives and mazes of online records, he may finally have found the leads to crack it.

Retired Portland Police Officer Henry Groepper

Cause and effect can be blurry when it comes to maladies suffered by police officers and firefighters. Statistically, both contract hepatitis, hernias, pneumonia, AIDS, tuberculosis, and heart disease at much higher rates than other groups of comparable age, courtesy of stress, toxic conditions, and struggles with uncooperative and, sometimes, drug-addled suspects. Today, all cops and firefighters in Portland receive lifetime benefits to pay the costs associated with on-the-job disabilities. Voters stepped up to protect their protectors, approving the benefits through a 2007 ballot measure that the Oregon Legislature later expanded to include certain cancers for firefighters.

But the cops of Groepper’s era got a different deal. Their contracts both predated the ballot measure and did not include enrollment in the Public Employees Retirement System, or PERS. Reasoning the officers’ pensions would be large enough to cover their future health care premiums, the city never even paid into Medicare, workers’ comp, or Social Security on their behalf.

Marcia Maple, age 76, for example, spent 26 years as a Portland police officer, serving in the historic Women’s Protective Division (the first in the nation to give female officers powers of arrest). In 1970, she contracted Hepatitis B on duty when she diapered the ill child of a dying woman. Since retiring in 1995, she’s racked up $47,000 in insurance premiums. In the course of his 26 years on the job, vice cop Brian Duddy required four surgeries on his shoulder, one on his back, and two on his elbows from endless chases and dust-ups with suspects. He retired with a heart condition in 2003. Today, the 62-year-old pays $640 each month for insurance coverage; the city pays nothing. Lanny Bennett, a 27-year veteran who supervised patrols on lower Burnside in the days when it was an alley of drugs and prostitution, was diagnosed with an abnormal heart rhythm in 1987. Since retiring in 1998, he has had valve surgery and a pacemaker installed in his chest. Now age 64, he pays $1,300 a month for a benefit package that includes his wife. The City of Portland’s contribution? Zero.

Maple, Duddy, and Bennett all retired from the city with approved disability claims for diseases acquired on the job. But none has ever received the benefits they believe the City of Portland promised—benefits that are now routinely provided to current officers. (Groepper got his cancer coverage on a technicality: he retired while out of work on disability.) Because of their often-debilitating preexisting conditions, buying their own health insurance and life insurance is expensive, and sometimes impossible.

“I just turned 67, and I’m trying to work. My wife is out of work. It’s a real challenge right now,” says Lennox Stanley, a retired police officer who became a private security guard, in part, to cover the $75,000 he’s spent on medical care for heart disease since leaving the Portland Police in 2003. “If we would not have had to pay that, we would have been able to save more for our retirement. We would have enjoyed a better life.”

The Portland Police Bureau’s employee manual, in effect during these officers’ tenure, clearly states that the city owes them more. Section 410.00b reads: “medical, dental, vision, and city paid life insurance premiums will be paid . . . indefinitely” for police who acquired occupational diseases on the job if they joined Portland’s Fire & Police Disability & Retirement plan after 1988 and retired before 2007.

But the City of Portland claims that wording was a mistake. In 2005, its lawyers successfully beat a lawsuit brought by Groepper and seven other officers, in part, by arguing that then–Chief of Police Charles Moose added the language to the manual without authority. The collective bargaining agreement negotiated with police and firefighters in 1993 and ’94, the city’s attorneys contended, sets the binding rules, and it contains no such promise of benefits.

A judge agreed. But on appeal, Groepper and his attorneys argued that the provisions were added to the manual later to provide parity with new employees who were contractually entitled to more benefits.

State law requires all minutes from the many arduous bargaining sessions necessary to change the manual and any contracts be kept for 75 years. The city claimed all pertaining documents were lost or irretrievable from an old computer system. Lacking any evidence to challenge the lower court’s ruling, the Oregon Court of Appeals affirmed it without opinion on August 29, 2007.

But Cold Case remained determined. “All [the city] was doing [in the manual] was giving all the cops with occupational disease disabilities the same benefit,” Groepper says. “How they fell through the cracks, that’s a question only those documents can answer.”

Groepper’s house has a storybook exterior, its steeply pitched roof rising into the trees on a verdant, sloping lot in unincorporated Clackamas County. But inside, most surfaces, from the kitchen counter to the dining room table, are covered in tall stacks of paper and boxes full of city and union documents.

Joined occasionally by Bennett, the former Burnside patrol sergeant with a heart condition, Groepper has patiently stalked city bureaus, pillaging the personal files of Charles Moose and other past police department managers. He estimates he’s spent thousands of hours pulling documents up through the city’s web-based document archive system, digging through the archives of both the city and the Portland Police Association, the local union.

In the 1990s, City Hall and labor unions hashed out every detail of police and firefighters’ benefits in brass-knuckle bargaining sessions, spelling out the results line by line in both the collective bargaining agreement and the employee handbook. Both were, and continue to be, two of the most fussed-over documents in City Hall. That one person—even a chief of police, as the city argued—could add language to the handbook seems far-fetched, to no one more than Moose himself.

In the 2005 lawsuit brought by Groepper and his colleagues, Moose was never deposed or called to testify. But interviewed by phone from his home in Tampa, Florida, he flatly denied he ever added—or even could have added—benefits, given the elaborate process of writing and rewriting, with each twist in the bargaining and review vetted by staff and lawyers. Moose’s remarks were echoed by Mark Sponhauer, then an officer in the planning and support division and now a detective for Portland Police. Sponhauer oversaw such changes at the time, and in a deposition confirmed that all documents traveled a wide circuit of stakeholders.

Image: William Anthony

“The city has tried to say I was over there going rogue and I was just sitting in an office writing things,” said Moose. “There are days that I wish. But there was definitely a system of checks and balances.” He flatly called the city’s allegation “insulting.”

Lawyers for the officers subpoenaed the documents from the city, asking for the full historical file from the 1993–94 bargaining sessions that would have included notes and minutes from meetings with the unions. After a “diligent” effort to locate them, the city’s attorneys claimed no records could be found at all relating to the manual change. But in recent years, Groepper’s own search has turned up at least a few of them.

There’s the memo written to Moose by Sgt. Darrel Schenck, which shows the benefits were reviewed and revised by many city leaders, not just dropped in the police manual. Schenck notes language in the manual “has had extensive reworking and numerous drafts” and was approved by key city managers.

There are the notes from city employee Rebecca Gunther that show the benefits were discussed in bargaining sessions October 6, 1993.

There are also notes from the Portland Police Association from the October 6 discussion, as well as from subsequent meetings November 23 and December 22, 1993, and March 7, 1994, which show the benefits were explored not only in formal negotiating sessions with the city, but also in smaller meetings between the union and Portland’s Police Bureau and Bureau of Personnel Services.

But Groepper’s most potent discovery is Michael Sims, the information systems manager who implemented the computer storage system that the city claims it can no longer access. In a recent affidavit Groepper solicited from Sims, he states bluntly, “The documents Henry Groepper is seeking are stored or archived on the Novell system, on disk and/or tape, and [are] readily retrievable.”

The discovery, Groepper thinks, spells victory for him and his colleagues. For the City of Portland, it potentially represents untold millions of dollars. Duddy alone would cost the city $7,680 a year for health care premiums. Multiply that by 110—and possibly by another 89 for the number of disabled firefighters who Groepper believes have also been unfairly denied benefits—and that’s more than $1.5 million annually in liabilities.

In a January 27 letter, Groepper asked the Multnomah County District Attorney’s Office to order the City of Portland to produce all missing notes and minutes from the bargaining sessions with unions, or to issue criminal penalties against whoever destroyed them. Presenting his findings as evidence the documents once existed, Groepper even offered to pay a computer technician to retrieve the remaining records, using methods suggested by Sims.

Deputy District Attorney John Hoover denied the appeal April 28, saying his office “is not in a position to order a public agency to disclose records that they have represented cannot be found.” Hoover has worked with the city, however, to broaden the search for the documents, an effort that could allow Groepper and his experts to search the computers.

As talks continue, City Hall remains silent. Current Mayor Sam Adams was chief of staff for Mayor Vera Katz when the benefit landed in the police manual. But his spokeswoman, Amy Ruiz, said, “At this time, as the issue may be headed toward further litigation, the Mayor’s Office is declining to comment.” Commissioner Randy Leonard, who headed the firefighters’ union in that era and would have attended the benefit negotiations, also declined to comment, saying he has not been involved with the dispute and can’t be of help. Commissioner Dan Saltzman, who today oversees the Fire & Police Disability & Retirement Fund, also declined to be interviewed, though his staff provided historical details helpful to assembling this article. David Shaff, administrator of the Portland Water Bureau and the labor relations manager for the Bureau of Human Resources when bargaining took place, said, “I would bet the city attorney would be very unhappy with me if I went off and met with reporters.”

After years of debating the issue with the city, both in court and out, Groepper is simply eager to see the situation come to a just end. Despite his ongoing fight with cancer, Groepper says that given the chance to rewrite history, he wouldn’t trade his days of busting meth labs, even when he had to strip down on the front porch once home, mindful of how the stench of his clothes irked his wife and kids. “Would I trade my police career? No. I loved being a police officer, I really did,” he says. “Would I trade working for the city of Portland? I would.”