Contraception: Not Your Mother's Birth Control

Call them what you will—generation Y, generation next, echo boomers, millennials. They probably won’t answer you anyway. Generational identity isn’t a big thing for the young women who are now in their 20s and early 30s—they’re too busy piecing their lives and careers together in a new economic landscape. For many, kids don’t fit into that puzzle quite yet.

“Women are, overall, tending to delay childbearing,” says OHSU assistant professor Dr. Kathleen Wilder, whose professional focus is on contraception and adolescent reproductive health care. “They’re wanting a method that is very reliable, that lasts longer, that they don’t have to think about every day.”

Nationally, the combination-hormone birth control pill is the most popular contraceptive choice for women under 30, as it has been for much of the half-century since “the pill” was introduced in the United States. Dr. Wilder, who sees many millennials in her obstetrics and gynecology practice, confirms the trend—for now.

“The pill has been the most popular choice for many years, and it is by far the most commonly used among women of that age group,” she says. “But we definitely are seeing a bit more of a shift toward what we call the long-acting reversible contraceptive methods—implants and IUDs.”

Intrauterine devices, or IUDs, are now one of the most commonly used contraceptive methods in the world. In this country, however, the IUD has only recently begun to shake the stigma that has clung to it since the Dalkon Shield was taken off the market in 1974 amid thousands of lawsuits over severe injuries, infertility, and even deaths caused by the poorly designed device. Dr. Wilder thinks it’s about time.

“We now have two very safe, extremely reliable IUD options that are bringing it back,” she says. “The two available in the US right now, the Mirena and the Paragard, are designed differently. They’re easy to remove safely. We have so much research on them showing how safe they are and how effective they are that a lot of women are shifting toward them.”

A shift in birth control preferences over the years is common. “A lot of young women end up starting out on birth control for a medical reason—to regulate their periods and to limit blood loss,” Dr. Wilder says. “Then, as they become sexually active, they can transition to a longer-acting method or just continue on the pill. The pill also assists with preventing ovarian cancer and endometrial cancer, so you’re getting other benefits at the same time.”

And there’s another reason women are drawn to the pill.

“On the pill, you don’t really have a period—it’s technically a withdrawal bleed,” Dr. Wilder explains. “The cycle was designed that way back in the day to mimic a woman’s regular cycle and have her period be conveniently timed. But we know that you don’t actually have to have a period. So nowadays, when women are so active and it’s expensive to have a period, a lot of women are choosing to just skip it.”

Still, as millennials and other women are choosing to have children later, they need flexibility with their birth control options, too.

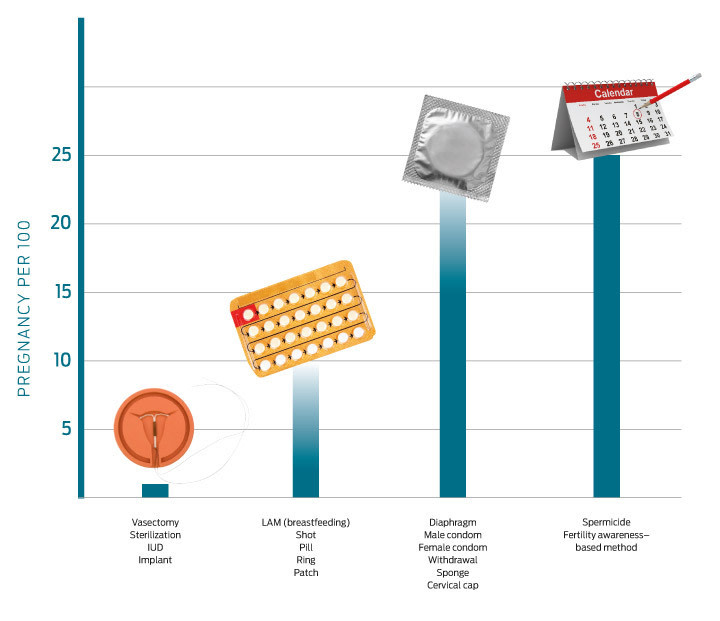

“Sterilization used to be common when you had women who were completing their families earlier, but now that women are delaying childbearing, they need a really effective method that’s both long-acting and reversible, such as the IUD or implant,” Dr. Wilder says. “Also, there are plenty of women who in the past would have considered sterilization, but now that they know they have an option that doesn’t require surgery but has the same effectiveness as getting their tubes tied, they’re jumping at that opportunity.”

Of course, IUDs and the pill aren’t for everyone. Women today have more contraceptive choices than ever before: not only familiar barrier methods such as condoms and the diaphragm, but also hormonal birth control options such as skin patches, injections, vaginal rings, and implants (Dr. Wilder advises her patients to use condoms in conjunction with any other options, in order to prevent the spread of sexually transmitted diseases.)

At the OHSU Center for Women’s Health, researchers are conducting clinical trials of potentially promising contraceptives, including a vaginal ring that’s effective for six months and an IUD that could be placed only three weeks after a woman gives birth.

In Dr. Wilder’s view, the more choices, the better. “That’s one of the great things about having so many options,” she says. “Some women hear about an IUD and say, ‘I don’t want anything inside me.’ They would rather do a ring, a patch, a pill, a shot. Other women want to avoid hormones, so the Paragard IUD is perfect. It’s ultimately a very individual thing.”