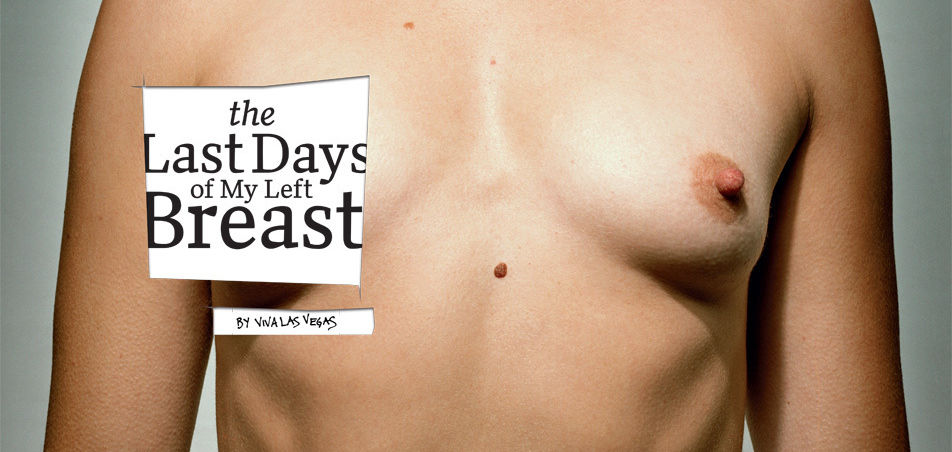

The Last Days of My Left Breast

You should see my tits. Right now. They’re quite impressive.

My right breast is an A-cup, a small, soft mound of flesh with a pert pink nipple the size of a half-dollar. It’s familiar, and looks much like it does in the countless photos and movies it’s appeared in over the past couple of decades. It’s not gonna stop traffic or anything, but it looks good. My left breast, on the other hand, maybe could stop traffic. It’s straight out of a horror film—the size of a cantaloupe and just as hard, skin stretched taut, with a long black trail of stitches on the side. The nipple is a psychedelic swirl of pinks and deep purples. The center of it is black. Black . Still, I have to admire the progress. The wound has closed up, and, apart from the nipple, the skin color is approaching normal. A week ago my breast was a giant yellow, green, and purple bruise, ringed with subcutaneous plastic tubing attached to a drain bulb.

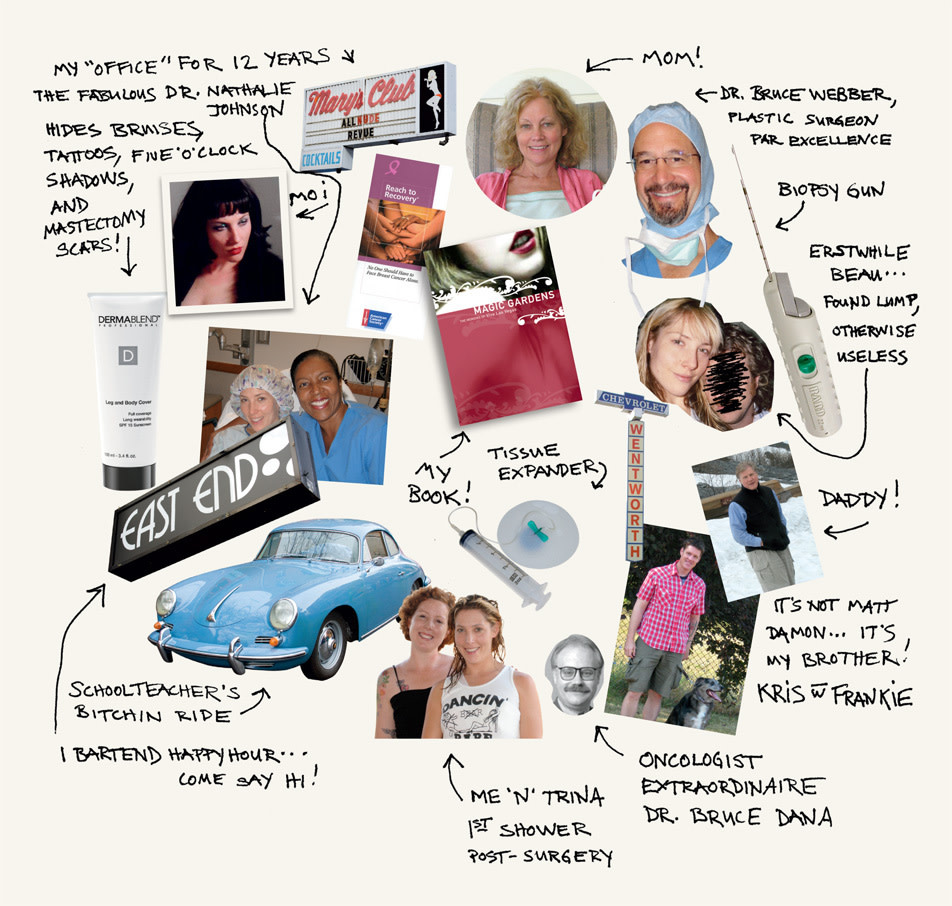

A week before that it looked much like its neighbor. My breast went to band practice to prepare for the Coco Cobra and the Killers reunion show, swam laps at Cascade Athletic Club, and worked way too hard juggling three jobs: stripping, bartending, and writing. It also took the stage at Mary’s Club one last time after twelve years—naked and proud throughout the strains of its swan song, the Stones’ “Doncha Bother Me,” rising and falling with thousands of breaths, and stoically covering for an aching, grieving heart. Then, on September 26, 2008, it submitted itself to the surgeon’s knife to remove some tiny bits of cancer that had taken up residence.

The following is a travelogue of my journey through the wilds of breast cancer, and an ode to a body part that always more than did its job.

Thanks for the memories.

R.I.P.

New home: Doc’s office

Image: Viva Las Vegas

Lump

Like most women, my entrée into the world of breast cancer started with a lump, found by my erstwhile beau during one of his routine “breast exams.” The lump wasn’t exactly difficult to discover: my breasts aren’t much more than lumps, and a lump on a lump is, well, noticeable. Still, if not for him, I wouldn’t have caught that gumdrop-size nodule over my heart for a good while longer. And cancer, as I’ve learned, really wrecks the place the longer it’s in town.

Next I did what any stripper would do and told the girls at the office. Strip-club dressing rooms can be potent nuclei of female power and amazing sources of information—like covens or sewing circles. The strippers said lumps are common. They also insisted that I see a doctor.

Down at Old Town Clinic, my nurse practitioner, Dana Mozer, fondled me thoroughly. After examining every centimeter of my breast, she pronounced that my lump wasn’t of much concern. Good lumps, like mine, move around; bad lumps stay stubbornly in place. Good lumps also grow and shrink, sometimes depending on caffeine intake, so we scheduled another appointment and I cut down on coffee—but two weeks later my lump was the same size. Although I was only thirty-three and have no family history of cancer—breast or otherwise—she booked me for my first mammogram.

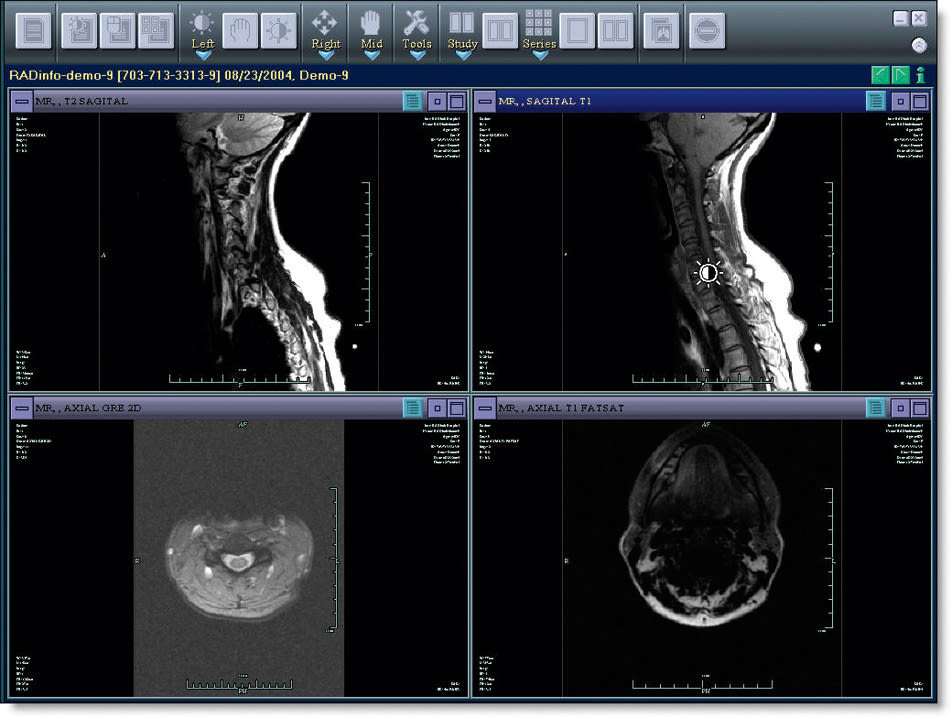

If this is virgin territory for y’all, a mammogram involves flattening one’s breast like a pancake between two hard plastic plates and taking images. My small breasts proved difficult for the pancake-maker to get hold of, so the scans had to be repeated several times. Next, I had an ultrasound, which can uncover abnormalities not revealed by the mammogram. Both the mammographer and the ultrasound tech thought my breasts looked perfectly normal. I was hugely relieved … until the overseeing doc came in, held up my images, and brusquely pointed out a handful of tiny white dots—calcifications that were suspicious for cancer. She ordered a biopsy.

I pursed my lips and tried to hide my irritation. So far the doctor appointments were primarily an inconvenience, but a biopsy? That meant losing a chunk of my breast! It also meant there might be something seriously wrong with me, yet all I could think of was what it meant for my mortgage. How would I strip with a chunk missing from my breast? How big would this chunk be? Would I be able to hide it with Dermablend?

The Wait

“The Wait” is my favorite Pretenders song ever. Its punk verve has steered me through many a rough patch. But the forty-eight hours between my biopsy and “The Phone Call” (another great Pretenders song) were a symphony of escalating anxiety.

I tried hard to put the questions out of my mind, and to convince myself that the tiny white dots were nothing out of the ordinary. Fortunately my mom was coming for her first visit in ten years, to see the house that my brother and I had bought and shared, so I distracted myself by frantically preparing for her arrival. I hadn’t mentioned a word of my breast adventures to my parents. I figured if I did have cancer, I’d spare them the agony and tell them at Christmas, when (hopefully) I was on the mend. If I didn’t have cancer, why worry them with the possibility that I did?

By Friday, my results were overdue, and I was quietly losing it. I left a message with my nurse practitioner, then headed to my bartending shift at East End, where ten friends coincidentally appeared on a whim to say hello (a clear sign that something bad was about to happen). I was busy slinging drinks when the doc’s office left a message. I stepped outside to check it.

The Wentworth Chevrolet building was wonderfully bright and angular in the late August sun. The building had probably been there a hundred years. I took refuge in its shadow and prayed to it that our circumstances would not change—it would continue to be its old self and I’d remain the healthy bartender across the street—and that my voice mail would contain nothing but good news.

“Hello, Viva. Your appointment with the surgeon is at 10 a.m. next Friday.”

My stomach sank and my hands started to shake. There was only one reason to see a surgeon: to get something cut. I frantically dialed my nurse practitioner, hoping to reach her before her weekend started. When I got her on the line, her voice held so much sorrow and empathy that I knew I was in trouble. Ductal carcinoma in situ Stage Zero, she said, and that she was sorry.

I walked back into the bar, told my friends I had cancer, then tried to hold it together while they fell apart. Somehow I made it through my shift. I drove home to my brother and mom—fresh off the plane from Minnesota—and chitchatted with them till they went to bed. Then I retreated to my back porch and, finally, wept.

Surgeon’s Girl

I’m an optimist. I believed that whatever cancer had set up camp in my body could be easily eradicated with a little knife-and-putty action, much like getting a cavity filled. It turned out I was wrong. Thank God I had my friend Trina with me when the verdict came down.

Trina is a fiery, perpetually smiling redhead who will do anything for her friends. Diagnosed with Stage 2B breast cancer in 2007—at age thirty-three and less than a year after giving birth for the first time—she’d been through a double mastectomy, chemo, radiation, and the attendant psychological vicissitudes. She took the morning off of work to drive me to my appointment.

In the surgeon’s waiting room at Legacy Good Samaritan Hospital, I picked through the available literature. Everything was pink and addressed to “survivors.”

I already hated the language surrounding cancer. It was the language of war: “battle,” “fight,” “survivor.” Honestly, I didn’t feel up for it. I was exhausted from overwork, nursing a broken heart, and literally world-weary after two decades of living with depression. What if I didn’t want to fight? What if I didn’t want to join the survivor clique?

“Do you call yourself a survivor?” I asked Trina.

“Fuck yeah I do! During much of chemo, it was all I could do to get through the day,” she said. “I lost my hair, both breasts, I have crazy scars. Hell yeah, I’m a survivor.”

A chipper young assistant led us to an examination room. She was so sunshiny and lovely that when she told me she had had exactly what I did—DCIS Stage Zero—and had gotten a double mastectomy, I didn’t succumb to shock. After complete breast reconstruction, she was clearly pleased with the results. “No more mammograms, I don’t have to worry about a recurrence, and although I wasn’t unhappy with my thirty-five-year-old breasts, my new breasts look like they’re twenty years old,” she gushed. “And they’ll look that way forever!” It was difficult for me to share her enthusiasm.

Judging by the online research I’d done, my surgeon, Dr. Nathalie Johnson, was one of the best breast surgeons in the Northwest and had received the proverbial Golden Boob Award at every breast cancer banquet and function. When she walked into the exam room, she exuded warmth and strength. She was also gorgeous, her dark brown hair graying slightly at the temples, her skin golden-brown, her smile huge. I immediately felt that I could trust her, and that I would do whatever she said.

Until she said: “Double mastectomy. That’s the treatment I recommend for women under thirty-five.”

I felt my eyes well up. Even after the assistant’s preamble, I had not expected to hear the word mastectomy. It was a huge blow, not necessarily because it meant losing my breasts, but because it suddenly put childbearing—something I’d always dreamed of but that wasn’t quite on the radar—front and center.

“What about nursing?” I asked feebly.

“Many women who haven’t had mastectomies are unable to nurse,” offered the assistant. “Just convince yourself that you’re one of them and make peace with that.” Trina and Dr. Johnson agreed; both confessed they’d had incredible difficulty nursing.

We reconvened in a conference room to discuss my options. I was lucky to have options—the cancer had been caught early—but that didn’t make the decisions any easier. The assistant gave me the phone number of a gal my age who’d recently undergone a mastectomy and reconstruction, and for the first of many times I heard the words: “She’s like you—she’s single.”

Yes, I was single. Trina was wonderful, but she was going home after my appointment to her princely husband and beautiful children. I would be sleeping alone. Probably forever, now that I was scheduled, in two weeks, to lose both of my breasts.

Damn dots. My films showing D.C.I.S.

Bearing Bad News

I didn’t want to tell anyone I had cancer. It felt like a personal failing, and I didn’t want anyone to think that I was weak, vulnerable. I didn’t want the role of the “sick person,” or for people to treat me any differently than they had. But now that I was going to have to take months off of work and undergo major surgery, the time had come to fess up.

For this I primarily relied on text messaging: “Bad news. Got a touch of the cancer. Double mastectomy in two weeks! Unbelievable.”

I was inundated with phone calls. My friends were furious, unbelieving, devastated. Instead of them comforting me, I had to comfort them , explaining over and over the details of the diagnosis and the reason for the aggressive treatment plan. Every single person considered a double mastectomy barbaric. In my doctor’s defense, I quoted statistics, and with each conversation my reality became more real, and I more at peace with it. By the time I went to my bartending shift, I was able to laugh cynically at my new joke: “Did you hear I’m getting a boob job? And a tattoo!”

Anyone who knew me was shocked. I’d been a stripper for twelve years, but apart from a few hard-earned scars, my body had looked the same since puberty. I’d seen a lot of great boob jobs in my line of work, but I never, ever wanted one. Ditto tattoos. My shtick on the strip stage was all about sincerity, and to me that meant baring the all-nude real me. Not to mention I’d always been a tomboy and an athlete, and I liked my barely-there tits. I was the last person who’d replace her breast tissue with gelatinous pads of silicone.

“You?! Fake boobs? Why?”

“Well, it’s free! My insurance is paying for it. Cuz … I have cancer!”

I thought my joke was really funny. Whatever patron I happened to be talking to would take a sip of whiskey and try to discern whether I was serious. And I’d blather on about my tattoo. Part of the reconstruction involved getting tattoos of nipples where my nipples had been. I thought that if insurance planned to pick up the tab for a tattoo, I might as well get something cool, like maybe the Ramones crest—the one with the eagle holding a baseball bat—or maybe the name of my other ex-boyfriend, Dickhead, in script over my heart.

During my downtime at the bar, I took a mental survey of myself. People clearly expected me to be more upset. I wasn’t. It sucked to have cancer, to be sure, but I didn’t feel depressed or even sad or angry. In fact, I felt more grounded than I had in a while, probably because there was something to focus my angst on, and, for once, a clear plan for my immediate future. Although I’d just begun my interaction with it, cancer seemed much easier than heartbreak or depression. Even the idea of being invaded by something that wanted to kill me lent a fresh perspective on life, and considerable relief.

One night at East End, I took out a pen, drew a line graph, and labeled it “Continuum of Things That Suck.” Heartbreak fell at the far end of suckiness, as did the death of a pet. Cancer was certainly worse than flying, or middle school, perhaps even worse than a friend’s betrayal. But I really believed heartbreak sucked the most. Or … maybe war. No! Urban sprawl . Urban sprawl was without a doubt the most corrosive thing I could think of, a constant source of grief and hopelessness. Cancer wasn’t nearly that bad; in fact, it fell more toward Stuff That Doesn’t Suck Quite So Much.

Three of my best girlfriends—the Stripper Mom, the Artist, and the Schoolteacher—interrupted my reverie. My diagnosis baffled them as much as it did me. They’d come to East End to get the details over a palliative cocktail.

“How will you nurse?! Do you know how important colostrum is for the baby? And the mother!” screeched the childless but well-meaning Schoolteacher. I wanted to punch her.

“Oh, God. Nursing’s not that big a deal,” said the Stripper Mom. “But Viva, how are you going to survive? How long do you have to take off work? Do you have insurance? God … We need to marry rich! Now!”

Taking a drag off her cigarette, the Artist said, “Haven’t I always said you’d make an excellent trophy wife?”

I felt like I was watching a Greek tragedy of my life, with my gal pals as chorus, voicing my three biggest fears: I wouldn’t be able to nurse my theoretical children.

Although I had insurance, I had no extra cash to sustain me for the three months I would have to miss work. And my stripping career was, in all likelihood, over.

I would make an excellent trophy wife. Or would have, until cancer butchered my chest and did God-knows-what to my insides. I figured I’d never date again.

Rebel! And Research.

As the shock of my diagnosis wore off, fears and doubts began to surface, along with a million questions. Did I really have to get a double mastectomy? Did I have to do anything at all? If I did get the surgery, how would I cover my bills? And could my rock band still play a show on Halloween?

Also, why did I get cancer at thirty-three? It didn’t make sense. I was always very solicitous about my health—I ran, swam, got regular acupuncture, had been nearly vegan for two decades. Yes, I worked in smoky bars, but only ten to fifteen hours a week. I never smoked. I drank, but rarely to excess. The culprit had to be stress. Or …

Friends chimed in with all sorts of unhelpful statistics. For instance, women who work nights evidently are more likely to develop breast cancer than women who work days. Another stat you won’t see widely advertised: women living in the Pacific Northwest have some of the highest breast cancer rates in the nation, which some experts attribute to lack of sunlight. One friend blamed my cancer on the terrible sunburn I’d suffered after my one ill-advised tanning-bed experience. Another friend blamed my ex: “The cancer is right over your heart. Your poor heart’s been through hell the last few years. That has to have something to do with it.”

My next move was to rebel. Who were these doctors, and why were they plotting against me? My cancer was Stage Zero. Zero in my book meant “nothing.” What if I did nothing? The more I thought about it, the more I fell in love with that option. I could keep my breasts, keep a close eye on the rogue cells within them, and start meditating regularly. Some people call this “denial”; I, however, just decided I needed a second opinion.

Soon I had an extensive list of naturopaths, acupuncturists, and breast cancer “survivors” to consult. I spent hours online, gathering information. I maxed out the minutes on my phone plan. I read all the breast cancer bibles, drank tumor-fighting potions (baking soda and maple syrup, anyone?), researched juicers (to get started on the recommended raw food diet), and signed up for breast cancer yoga, acupuncture, and even a cancer writing group. I talked to every breast cancer survivor I could, met them for drinks, and groped their reconstructed boobies in the dark bathrooms of hipster bars. I faxed my pathology report to doctor friends around the country. Without exception, every healer—whether hippie, holistic, occult, or orthodox—insisted I get the cancerous tissue surgically removed. Immediately.

Yet as the surgery date loomed, I panicked. I canceled my surgery and instead scheduled another consultation with Dr. Johnson.

For emotional support, I dragged my brother along. We found Dr. Johnson in surgical scrubs, presumably ready for a day of removing breasts, two of which should have been mine. She calmly addressed every doubt, fear, and question I had, including my fantasy of doing nothing. But she was much more stern with me than she’d been at our first meeting. We reviewed my mammogram. The first time I saw it, the white dots had looked so harmless; now, having spent two weeks in cancer boot camp, they looked much more sinister, and more numerous than I remembered. According to Dr. Johnson, I needed them out of there, ASAP. I blinked back tears, knowing deep down that she was right.

Later that day, I e-mailed my father. It killed me to write it—the news would break my dad’s heart. I felt like a complete and total failure. We were a family of health nuts and athletes. No one had cancer. No one except me.

Thankfully, I had a shift at Mary’s that afternoon. Of all the people I knew, I most wanted to be with my dancer family. They were generous and empathetic. They knew what it meant to rely on your body to make a living, and also the implicit terror in having that body fail you.

The annual Komen Portland Race for the Cure was coming up. The huge sign-up sheet that had appeared in the Mary’s Club dressing room was covered with names—girls who would walk, along with the names of all the people they’d lost to breast cancer.

On the morning of the race, a group of us gathered outside Mary’s. Eight in the morning is very early for strippers. But there we were, bundled against the chilly fall rain. We ambled down to the waterfront as a group. Forty thousand people were expected to attend, and as I waded through the crush of balloons, hats, head scarves, and wigs, I quickly became overwhelmed.

I spotted three cowboys in Carhartt work jackets and boots—tall, strong, handsome men, bent with grief. They carried a small sign with a name and photo on it—the older gent’s wife and the younger ones’ mother, I imagined. I choked up at the sight of them.

In five days, I was losing my breast. The Race for the Cure was the last place I wanted to be.

“I have a grand idea,” I whispered to my two best pals. “Let’s drink for the cure instead.”

We marched with the throng down SW Broadway, past Mary’s Club, then veered right into the front door of Embers. A fabulous bartender welcomed us warmly, poured us strong Irish coffees, and offered biting fashion critiques as the parade of pink surged solemnly by. Halfway into my whiskey coffee, I felt significantly better. We agreed to make Drink for the Cure an annual tradition.

The next four days were a blur. I met with my publisher regarding my book, due out in August. My band, Coco Cobra and the Killers, practiced one more time, in the hopes that I’d be back for our Halloween show at East End. I sat for a photo shoot, and, with my beloved writing group, planted hundreds of spring bulbs in my front yard. Clearly, life would go on after surgery. I just wasn’t quite sure what it was going to look like.

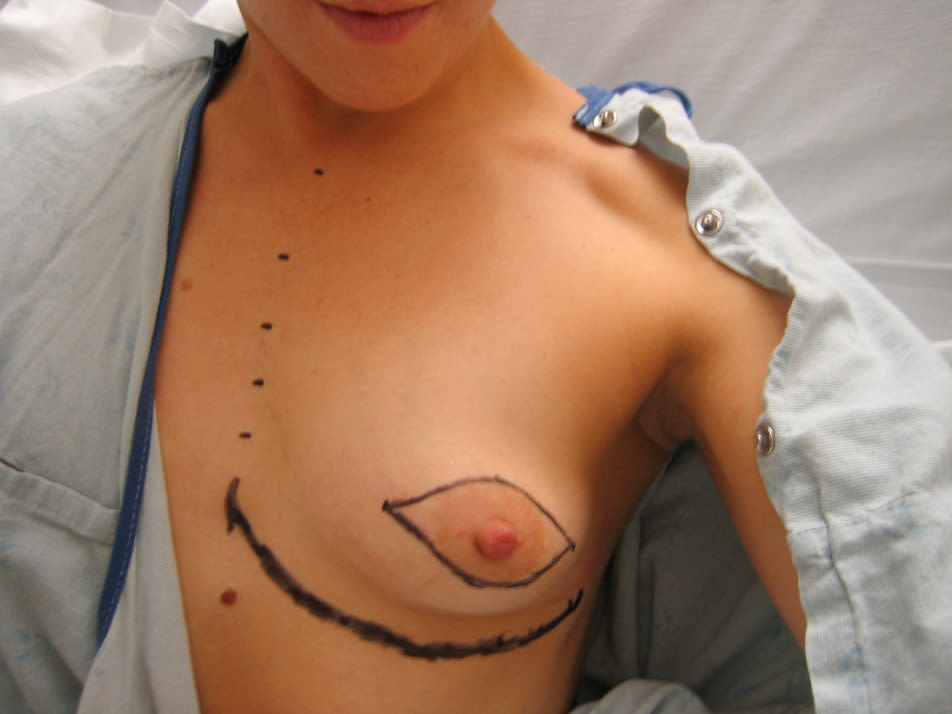

During this time, my plastic surgeon, Bruce Webber, and I discussed what many people had recommended all along: take only the cancerous breast and leave the other one alone.

In retrospect, it’s strange that I hadn’t considered this option more seriously. I’d been so buried in information, processing the opinions of a dozen different doctors, that I saw my choices as all (double mastectomy) or nothing. Thank God for Dr. Webber. I loved the way he talked to me: no-nonsense and not patronizing in the least. I trusted him. And with his advice and approval, I arrived at my decision. The relief that accompanied it was intoxicating. I could finally let go of all the chaos, grief, and fear. I would lose a breast, but I would keep my sanity.

Dr. Webber’s cut lines: He’s quite the artist.

Party of the Century

And so, on September 26, I underwent a unilateral mastectomy. Dr. Johnson removed my left breast along with several lymph nodes for biopsy; Dr. Webber put in a tissue expander to start the reconstruction process, pumped it up with saline, and stitched me back together.

Because of the extent of the calcifications in my left breast, there was some worry that my cancer might have been invasive. After surgery, when I briefly came to, the first words I heard were that my lymph nodes were clean. The doctors also told me that my nipple had been salvaged, which I had no idea was even possible. I fell back asleep, hugely relieved. The next time I woke, I was in the midst of a party.

My mom had flown in, as had my buddy from New York. The Schoolteacher took the day off, and my brother stood by to do my bidding and send text updates to anyone who cared.

A lot of people cared. They gathered around me in my hospital room, drinking wine and watching the presidential debates, keeping me company as I came out of the anesthesia. By the next afternoon, the party had outgrown my hospital room and I was more than ready for a change of scenery. As soon as the nurse unhooked my IV, I was out the door. The Schoolteacher picked me up in her ’61 baby-blue Porsche and we rode to my house in style.

Someone had thoroughly scoured the place during my brief furlough; there were flowers everywhere, and my dog had been farmed out (I was on strict orders not to walk—even around the block—for two weeks). Guests started arriving almost immediately, loaded with more flowers, groceries, books, and DVDs. My mom started an enormous pot of chicken soup while my ersatz mom, Vicki Keller, the owner of Mary’s Club, critiqued the recipe. Bottle after bottle of wine was opened and consumed (not by me) while I lounged on the daybed like Cleopatra, basking in all the love and attention.

The party held steady for two weeks. People I didn’t even know showed up with casseroles and stews, while long-lost acquaintances resurfaced with stories and babies to brighten my convalescence. I’d never recommend cancer to anyone, but I have to say that the weeks following my surgery are among the most treasured in my life.

Every day held little triumphs. Although most of the post-mastectomy tales I’d heard saw the patient laid up for a week, unable to so much as wrangle pajama pants, I insisted on avoiding loungewear. I was overjoyed when I found a dress I could slip over my extensive bandages (one gal pal said I looked like I’d been dressed by Azzedine Alaïa), and ecstatic when I discovered I could cautiously pull on a pair of jeans with one arm, and button the fly. Having my hair washed felt like a huge achievement, as did taking my first shower. Trina came over to help me with the latter, and together we unwrapped my new body part.

I couldn’t look. But when Trina gasped and said it looked great, I peeked. There indeed was a breast. A black-and-blue and scabbed and swollen breast, but a breast all the same.

Christ in the Desert Monastery

Image: Viva Las Vegas

Motorcycles, Monks, and Money

That was supposed to be the end of the story. My mastectomy was supposed to have “cured” me. And I was planning, after a couple of months, to never think about breast cancer again. Unfortunately, things didn’t quite work out that way.

The dissection of my breast tissue uncovered a tiny tumor that was highly aggressive—and that raised the possibility of lymphovascular invasion. In lay terms: although my lymph nodes were clean, cancer cells may have escaped the breast ducts into the bloodstream, where they could travel anywhere in my body, most ominously to my bones, lungs, or liver.

The words “may have” caused me considerable consternation. For the first time, I was assigned an oncologist, and then a second, and then a third. The statistics were in my favor: it was 80 to 90 percent likely that the surgery had “cured” me, but if the cancer was on the loose and invaded my bones, lungs, or liver, it almost assuredly would be fatal. Although chemotherapy reduced my already slim odds of recurrence by only 30 percent, two of three oncologists recommended it, as did every naturopath, acupuncturist, and friend.

Once again I was faced with an agonizing decision—whether putting my body through chemo was worth such a slight reduction in risk. And again, the irony of my situation bemused me. I was lucky: I had options. By the time many women discover their cancer, their decisions are made. I could choose whether or not to have chemo. Still, for me, the decisions were the hardest part; decisions didn’t feel like much of a luxury.

After four weeks of considering various treatments and assembling professional opinions, I was a wreck. If I hadn’t felt like fighting for my life before, now I felt less like it. Usually when I’m that low, climbing on the back of a motorcycle is the only remedy. Although the plastic surgeon forbade such activity for two months post-surgery, I felt the benefits outweighed the risks. One glorious fall day I cruised around the West Hills on an old Honda, holding tight with my good arm to a Tennessee stud. For a couple of precious hours I felt like myself again, and the positive effects lingered a full two days.

Protocol required that I begin a course of treatment within three months of surgery. As time ticked away, I came more undone. I cried without provocation, my mind close to meltdown. The money thing became far more distressing as my illness threatened to command more of my future. I didn’t know when I’d go back to work and had no idea how I would pay my bills. Without my friends, I would have been lost. They fed me, entertained me, and every time I got down to my last six bucks, some hero swooped in with a tank of gas, a bag of groceries, a free massage, a stack of hundreds.

Finally, perhaps hearing the distress in my voice, my biggest hero of all set his own rescue plan in motion. For years, my dad, a Lutheran minister, had been prodding me to visit a monastery, promising that the silence and prayer would center and ground me. Convinced I needed sun with my silence, Dad insisted I take a trip south and booked me for a stay at the Monastery of Christ in the Desert in the Chama Canyon, just north of the tiny town of Abiquiú, New Mexico.

Which is how I found myself breaking bread with twenty Benedictine monks for a full week last November. I prayed and meditated and chanted and hiked in the desert. Slowly, I came back to myself. The tears dried up after the first few days, and I felt my soul start to return to its center. By the end of my stay, my smirk was back in place. During a silent lunch, I laughed out loud in spite of myself when the thought crossed my mind that I’d been in a similar situation countless times: a woman alone in a room full of men—but in the past I was almost always naked.

I came home from New Mexico happy and calm, and I met my oncologist, Dr. Bruce Dana, with a clear head and an open heart. I realized that, contrary to my alleged lack of fight, I had been fighting since Day One of my diagnosis. I was fighting loss, fighting change, fighting reality. And though I finally admitted life was worth fighting for, perhaps fighting wasn’t actually the best way to handle things. Once I relaxed, the decision came: I would do chemo.

Sex, Drugs, and Rock 'n' Roll

Coco Cobra and The Killers

Image: Viva Las Vegas

Healing is a process, both mental and physical. My body and my mind have had to stretch and grow in ways I wouldn’t have thought possible pre-cancer. We’ve got a long way to go, but I’m confident that by summer I’ll be rockin’ a lovely new rack. And I’m looking forward to the punk possibilities of post-chemo hairstyles. Hopefully my mind will rebound in like fashion (if not, there are always those monks in New Mexico).

Already my left breast has stretched to accommodate two giant injections of saline. To me it looks huge, especially next to my A-cup right breast, but that didn’t stop me from flaunting them both in a fishnet shirt at the Coco Cobra and the Killers show on Halloween. After chemo, both breasts will undergo another surgery: the expander pouch in the left breast will be swapped for a silicone implant, and my right breast will be augmented to match. Although it’s nothing I ever aspired to, for the first time in my life I’ll have a proper pinup body.

I’ll be seriously into pharmaceuticals for quite a while. After chemo, I’ll start a five-year course of tamoxifen and a year of weekly injections of Herceptin, a designer drug that, at $8,000 to $10,000 a shot, will make me the Gal with the Golden Arm. I’d much rather be planning a sabbatical in New York City or a pregnancy, but for now, those things have been shelved. I’ll be in Portland for the foreseeable future, basking in the love of my friends, playing music, and promoting my book while comforting gals newly diagnosed with breast cancer and letting them feel me up in dark corners of hipster bars.

And maybe, just maybe, I’ll do a few cameo appearances on the stages of the downtown strip joints I have loved so well, slinking around in the buff to the Rolling Stones, preaching that all bodies, no matter what strange adventures they’ve been on, are beautiful.