Checked Out

“Well?” asks Kathy Wilson, the office manager at Indian Hills Elementary School in Hillsboro, pulling open the library’s purple double doors. “Does it look the same?”

I glance around at the worn blue carpet, the chin-high orange shelves, and the chairs that look like they could hold just half of my now full-grown rear end. It’s been 20 years since I last stood in this skylit room, the place where I fell in love with books. At lunchtime, my best friend, Kimberly Honeycutt, and I would raid the shelves, taking our finds over to “the magic square,” where two steps cut into the floor created a kind of amphitheater in miniature.

In many ways, my imagination was born on those steps, where we laughed at Curious George, solved crimes with Nancy Drew, and followed Alice through Wonderland. When we decided we wanted to be doctors, Ms. Hawes, the librarian, guided us to the anatomy section, where we devoured Kathleen Elgin’s series The Human Body. And when we decided we wanted to be baseball stars instead, Ms. Hawes sent us outside, but not without first making sure we’d checked out a book on Babe Ruth.

Yes, it all looks familiar, just smaller. I can even make out The Human Body series—on a shelf near An Inconvenient Truth. But something seems to be missing.

“Where’s the librarian?” I ask.

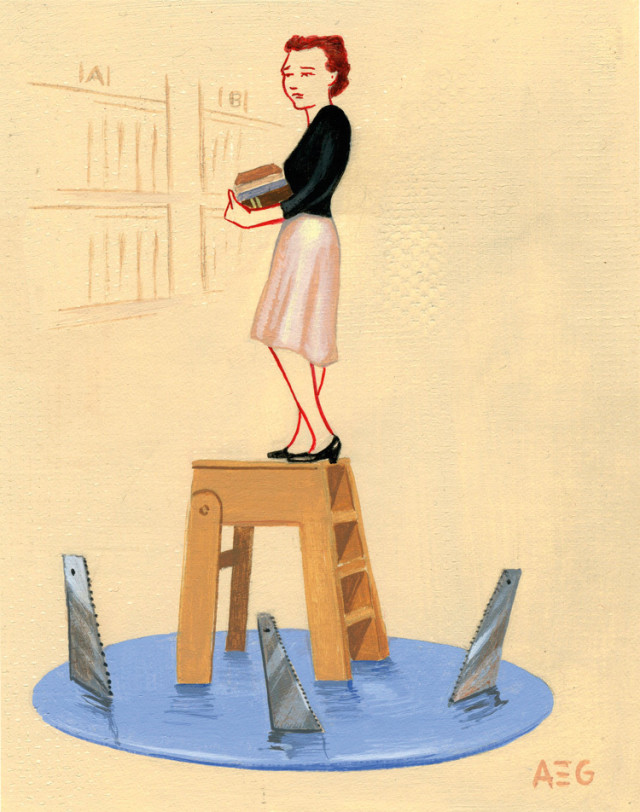

Gone. And not just for the summer. Five years ago, tighter budgets forced the school to get rid of her position, and Indian Hills isn’t alone. This spring, Marshall High School announced that it would eliminate its librarian position beginning in the fall (although it will keep a clerical library assistant), just as Roosevelt High School did in 2006. In fact, of the 81 schools in the Portland Public Schools district, only 18 had full-time certified librarians last year. And Portland isn’t the only place where librarians, apparently, are expendable: Across Oregon, according to state librarian Jim Scheppke, the number of school librarians decreased from 819 in 1980 to 389 in 2006.

The loss of our school librarians doesn’t just mean the disappearance of someone who reshelves the latest Harry Potter volumes. It means losing a vital member of the teaching staff, one who is devoted to getting young people excited about reading. Or, at the very least, lukewarm about it. Consider that between 1992 and 2002, the number of 18- to 24-year-olds who read for pleasure dropped by 7 percent, according to a 2007 report by the National Endowment for the Arts. The same report found that today’s 15- to 24-year-olds spend less than 10 minutes a day on voluntary reading, and that 35 percent of high school seniors are able to read proficiently.

Of course, not all of these grim statistics can be attributed solely to the disappearance of librarians. Digital distractions like the Internet might account for some of the diminished interest in books. But, somewhat paradoxically, that same digital culture has driven more people to libraries than ever before—at least electronically, says Gregory Lum, president of the Oregon Association of School Libraries. In the past, finding an old National Geographic article required trudging to the library to scan through rolls of microfiche, but today’s students can access articles remotely through a library’s database system. That ease of access means more people are using libraries as a resource, even if they aren’t paying visits in person.

It also means that today’s librarian is charged with managing not only books and card catalogs (yes, they still exist), but also online databases like ERIC, a collection of more than a million articles relating to education. And they must make sure students know how to navigate these systems. “Today there’s more information, and more access to it,” Lum says. “But there are fewer people to guide students.”

Of course, no school wants to cut librarians, but faced with the choice between losing a classroom position or a librarian, many administrators decide to send the librarian packing. They shouldn’t. Since the 1950s, more than 75 studies have been carried out on the link between school libraries and academic achievement. Study after study has shown that students at schools with high-quality libraries (meaning, in part, those staffed by a librarian) achieve higher reading scores and perform better in the classroom than students who lack those resources. Which makes the loss of school librarians an equity issue.

“One school in the district has a librarian, an assistant, and a book clerk,” says Susan Stone, president of the Portland Association of School Librarians. “That’s a wonderful model, but Marshall doesn’t have that. If Portland is all about equity, how does that work?”

It doesn’t. But it also doesn’t have to be that way. Not if the state makes funding libraries a priority for all schools in all districts. The proof lies just north of the border. There, three women from Spokane, Washington—Lisa Layera Brunkan, Denette Hill, and Susan McBurney—lobbied the state legislature to set aside funding for school libraries after learning that their district planned to reduce 10 librarians to half-time. After nine months of lobbying, the women’s campaign, Fund Our Future, succeeded in getting $4 million set aside for school libraries across the state, inspiring Arizona and Oregon to try similar Fund Our Future efforts.

“But that money was just supplemental,” says McBurney. “It won’t be there next year; we need to find a long-term solution.”

So does Oregon. Here, only 5 percent of school libraries meet the standards for adequate staffing (one certified librarian and an assistant) and resource acquisition set out by the state’s Quality Education Commission. In Multnomah County, only two schools—Madison High School and Beach Elementary School—meet them. In the Hillsboro School District, to which Indian Hills belongs, none do.

“There’s no library time anymore,” Sue Keane, an Indian Hills teacher and former librarian, tells me when she stops by the library. “Just 30 minutes of browsing and check-out time once a week for each class.”

I survey the room once more, and my eyes stop in the space where the magic square should have been.

“Hey, what happened to the magic square?” I ask Keane.

“Oh, that’s been gone for years,” she says. “I think someone’s grandmother fell down and hurt herself or something.”

I walk over to the dark corner where I’d once spent so many hours accompanying Alice and Nancy and George on their adventures. I stomp on the floor. It’s hollow—covered with plywood and carpet. Gone. Given everything else that has disappeared over the last 20 years, the empty sound that echoes through the room somehow seems fitting.