Very Berry Blue

Blueberries are one of the most rewarding small fruits you can grow in your garden. They’re flavorful and packed with vitamins C and E, as well as other beneficial antioxidants thought to protect against aging and the damaging effects of free radicals. When in leaf, blueberry foliage also makes a fine contribution to the landscape. Perhaps best of all, picking ripe berries off a plant you’ve grown yourself is a definite path to nirvana.

Early spring and autumn are the best times to plant blueberries since the rain and cool temperatures help establish the plants. The largest plant selection is available in spring. But summer is when the truly serious blueberry grower gets started, sampling as many varieties as possible to decide which ones to plant. Consider it one of the few first steps in gardening that is instantly satisfying.

That said, blueberries aren’t for the impatient. Plan on two to three years before the first fruit appears. Nevertheless, the homemade pies, jam, or ice cream—or a handful of berries plucked straight from the bush—are well worth the wait.

{page break}

Know Thy Fruit

Although it’s painful to do, remove the fruit and flower buds from your plant for the first year—it really does make a difference in the plant’s growth. If you resist the temptation to let the fruit ripen in the plant’s youth, your discipline will be rewarded with bigger, healthier plants in the long term.

Blueberries (Vaccinium) are in the heath family (Ericaceae) and are related to heather and rhododendrons, as well as some 40 other Vaccinium species, including huckleberries, bilberries, and cranberries. They range from petite, bushy, lowbush blueberries (primarily V. angustifolium), which are perfect for pots, to the most common commercial blueberry, the northern highbush (mostly V. corymbosum).

Visit one of the U-pick farms in the area (pickyourown.org), or peruse local farmers markets for berries. Keep in mind that their flavor can vary widely from field to field and year to year, so adopt a scientific approach by sampling as many named varieties as possible and taking notes. Bernadine Strik, professor of horticulture and berry crops research leader at Oregon State University’s (OSU) North Willamette Research and Extension Center, gives a high flavor rating to the ‘Blueray’, ‘Darrow’, and ‘Spartan’ cultivars. And Gary Hongel, a blueberry grower in Brush Prairie, Washington, suggests trying ‘Legacy’ and ‘Bluecrop’, although he cautions not to pick ‘Bluecrops’ until they are fully ripe. As far as quantities go, start with two or three highbush blueberry plants per person, and see how much fruit they produce for your purposes.

Blueberries are self-fertilizing, but by growing more than one cultivar within the species, you can improve pollination and fruit size. Any highbush blueberry will pollinate any other highbush blueberry; any lowbush blueberry will pollinate any other lowbush.

{page break}

Prepare and Plant

Once you’ve picked a variety to grow, you’ll need to prepare your ground. Blueberries require well-drained soil that is slightly acidic and rich in organic matter. The soil’s pH should be between 4.5 and 5.5. Strik recommends testing the pH about a year before planting (another reason that July is the best time to start thinking about growing), so that you have time to adjust it if necessary. Tests are available for $20 at Wy’East Environmental Sciences Inc (2415 SE 11th Ave, wyeastlab.net).

Of course, most soil in western Oregon is slightly acidic, particularly near conifers and in undisturbed native soils. But if your soil is in an area that was limed in the past (such as a former lawn or vegetable garden) or is near new construction or concrete (which leaches lime), OSU recommends lowering the pH by adding elemental sulfur, available at Concentrates Inc (2613 SE Eighth Ave, concentratesnw.com) and feed stores like Wilco (multiple locations, wilco.coop).

If you’d rather take the organic approach, mix 3 inches of finely ground conifer bark or sawdust into your soil before planting. Try bagged Black Forest organic compost from Portland Nursery (multiple locations, portlandnursery.com) or fine-grade fir available by the yard from McFarlane’s Bark (13345 SE Johnson Rd, mcfarlanesbark.com). Blend the soil amendment with the native soil over an area at least 3 feet by 3 feet (or 2 feet by 4 feet if planting in rows). This improves drainage and lowers the pH over time. Organic growers will also mix 1 cup of bonemeal into the planting area to provide phosphorus, calcium, and more.

When choosing your planting location, remember that blueberries produce the best fruit in full sun with good air circulation and adequate water (1 inch per week for young plants; 1.5 to 3 inches per week for mature plants), particularly while fruit is forming. Highbush blueberries are best spaced 4 to 5 feet apart and can be planted in beds, rows, hedges, or singles, while lowbush blueberries should be spaced approximately 2 feet apart.

Mulch and Harvest

After planting, mulch your blueberries by spreading about 4 inches of fine fir bark over the root area, keeping material a couple of inches away from the plant’s base. Wait to fertilize your new plant until it has had a chance to settle in: say, late April or early May, with another round in early June and late July. With typical soil, Strik recommends using 1 ounce of ammonium sulfate or urea per plant in each round of fertilizing to lower the soil’s pH and provide nitrogen. Some blueberry growers use organic 8-5-5 in conjunction with 1 cup of bonemeal mixed into the planting area, and a foliar spray of Alaska fish fertilizer three times in September to provide boron and other micronutrients during bud set. Whatever you do, don’t use 16-16-16, a common mistake that slowly kills blueberry plants with salts.

These fertilizers are available at Concentrates Inc, Portland Nursery, and local feed stores. Sprinkle the fertilizer evenly around each plant, away from the crown and stems. Finally, regarding fertilizer: Some folks never use fertilizer and their plants do fine, so don’t fret unless your plant looks sick or doesn’t produce much fruit.

Once bushes produce fruit, blueberries are really easy to harvest: Just pick them ripe and eat them, or toss them straight into freezer bags to enjoy over the next year. Tip: A highbush blueberry reaches maximum sweetness and flavor about four days after it turns blue. Give it a few days to ripen properly on the bush, and you will be rewarded with richer flavor and sweetness.

Blueberry plants can have a productive life span of 50-odd years, providing decades of health, beauty, and sun-warmed fruit eaten by the handful.

{page break}

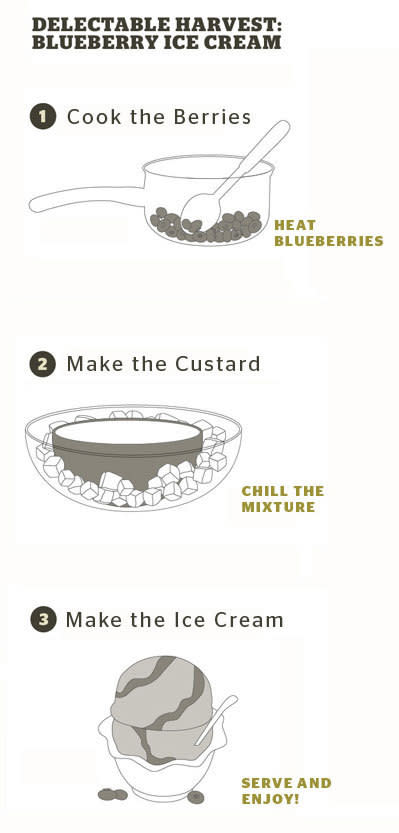

Delectable harvest: Blueberry Ice Cream

With summer upon us, the season is ripe for making icy desserts from one of the Northwest’s most delectable small fruits.

If you don’t already have an ice cream maker, buy a model that uses a pre-frozen canister that you keep in your freezer, ready to go. Try the Cuisinart Ice Cream Maker from Williams-Sonoma, $60.

This is a recipe for insanely rich blueberry ice cream, adapted from the vanilla recipe in David Lebovitz’s The Perfect Scoop: Ice Creams, Sorbets, Granitas, and Sweet Accompaniments (Ten Speed Press, 2007).

Ingredients

1 cup fresh blueberries

¾ cup sugar

1 cup whole milk or half-and-half

2 cups heavy cream

pinch of salt

1 vanilla bean, split in half lengthwise

6 large egg yolks

¾ tsp high-quality vanilla extract

1 tsp grated orange rind

Freeze the ice cream maker’s mixing bowl before beginning this recipe. Also, place a medium-sized bowl in the freezer for the finished ice cream.

In a small saucepan, heat blueberries and ¼ cup sugar over medium heat, stirring constantly, until blueberries begin to cook down, about 10 minutes. Set sauce aside to cool.

Warm milk (or half-and-half), ½ cup sugar, 1 cup cream, and salt in a medium saucepan over low heat. Scrape seeds from vanilla bean into the mixture and then add whole bean. Cover, remove from heat, and let steep at room temperature for 30 minutes.

Pour remaining 1 cup of cream into a large bowl and set a mesh strainer on top. Set aside.

In a separate, medium-sized bowl, whisk together egg yolks. After warm vanilla-cream mixture has steeped, slowly pour it into egg yolks, whisking constantly. Scrape mixture back into saucepan.

Stir mixture constantly over medium heat with a heatproof spatula, scraping the bottom as you stir, until mixture thickens and coats the spatula. Pour mixture through the mesh strainer into the bowl of cream then stir. Add vanilla extract, whisk in orange rind, and chill over an ice-water bath until cool.

Chill mixture in the refrigerator. When ready to churn in the ice cream machine, remove vanilla bean. Remove the ice cream maker’s bowl from the freezer and scrape mixture into the frozen bowl. Churn according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Remove medium-sized bowl from freezer, scrape ice cream into the bowl, fold in the blueberry sauce (do not mix), and freeze again.