Tree Hugging

I have many fond memories of my last house in Portland, but none sweeter than that of the ancient, 40-foot native dogwood (Cornus nuttallii) that grew just eight feet beyond a south-facing window. In the summer, I drank tea in the window seat and admired the tree’s smooth, gray trunk, which was shaded by its low-branching canopy. Nuthatches and bushtits patrolled for insects while squirrels chased each other in the branches. Light reflected from the creamy flowers lit up the room in spring, and in autumn, the tree’s fruit provided a feast for the birds.

This stately tree afforded me great pleasure—and helped keep the house cool and comfortable in summer. It also taught me a lesson: Choose and plant trees carefully. While the dogwood in my yard may have been planted by a bird rather than a garden designer, it couldn’t have been better situated. Its perfect position is undoubtedly why it endured the years without meeting the ax.

{page break}

Right Plant, Right Place

To choose such a specimen, let’s start with what you like (or don’t like) about trees: Do colorful flowers transport you, or do you resent having to wash them off your car’s windshield? Do you swoon with delight upon smelling a magnolia flower, or does it make you sneeze? Is leaf-raking an autumn ritual you relish, or would you rather go to the gym for your workout? What about growing fruit to eat or to attract birds? And of course there are practical matters, like shading your kitchen window from the blasting summer sun or blocking the view of your neighbor’s trash bins. It’s also crucial to assess the conditions you can offer a prospective tree: soil type, available moisture, possible root competition, microclimates, and any potential hazards from heavy foot traffic, vandalism, or deer. Once you’ve determined the inherent characteristics of your space, it’s time to carefully consider your options.

There are seemingly endless arboreal possibilities at local nurseries, in catalogs, and in books—so do as much research as you can before choosing. Take a look at Dirr’s Trees and Shrubs for Warm Climates: An Illustrated Encyclopedia by Michael Dirr (Timber Press, 2002) for some good ideas. Local designer and nurseryman Sean Hogan’s new book, Trees for All Seasons, due out this November, lists hundreds of evergreen trees suitable for our region. Also, compare trees at friendsoftrees.org/arboretum, which lists trees grown in the Ainsworth Linear Arboretum, a two-mile stretch of NE Ainsworth Street between NE MLK Jr. Boulevard and Fernhill Park that is planted with 57 tree species.

Some of these trees are better for our region than others. For instance, if you want a tree that requires no supplemental summer water once established, pick an Oregon white oak rather than a Stewartia, which would ultimately perish in a dry area. Or, if you plan to water the area where the tree will be located, try something that will improve the region’s tree diversity (like a crape myrtle or Eucryphia) instead of adding yet another maple or flowering cherry to Portland’s urban canopy.

For the most adventurous method of tree selection, explore local boutique nur-series (download our guide to Willamette Valley nursery tours at portlandspaces.net/tours). These homegrown plant nurseries often display a range of interesting trees in their gardens (and sell them, too), including underutilized Southern Hemisphere and Asian trees that do well with varying degrees of supplemental summer water, and some West Coast natives that thrive naturally in our summer drought and winter wet.

{page break}

Planning and Planting

Autumn is the best time to plant all but the most cold-tender trees: Warm soils encourage root growth and winter rains help with the task of watering. Just remember to thoroughly water your tree after planting it and continue to do so until then rain takes over.

When planting trees, the goal is to create an environment that will allow the roots to spread wide in their youth, both for stability and drought tolerance. If planted in late autumn or early winter, trees naturally receive an ideal growing environment (i.e., one that is cool and moist) for their first four to eight months.

Prepare a planting area that is no deep-er than the tree’s existing roots, and that is two to three times as wide. Digging a hole too deep (sometimes called a “tree grave” by experts) can cause the tree to sink below grade—a common cause of tree mortality. The correct planting depth can be determined by gently removing excess soil from the trunk to expose the root collar (the point where the flare of the trunk is widest and the uppermost root begins), which should be level with the soil’s surface.

If the tree is in a container, remove the pot, gently untangle the roots, and slice any circling roots with sharp clippers. If the tree is balled and burlapped (B&B), settle it so that it’s level. It is very important to avoid planting the tree too deeply, as it is difficult to raise it once planted. Remove any wire caging, twine, or burlap by snipping it away with scissors. (It’s OK if a bit of burlap remains attached to the roots, as long as it’s made of all-natural fiber.) Once in the ground, no burlap should touch the trunk or approach the soil surface.

Position the tree, spread out the roots, and backfill with the native soil. If you are planting in construction backfill or soil that is poor or compacted, select a tree that is tolerant of poor soil, like the Cornelian cherry dogwood. Mix in a couple of spadefulls of fine, wood-based compost ($7 per 1.5 cubic feet at Cornell Farm, cornellfarms.com; $9 per 3 cubic feet at Garden Fever, gardenfever.com). Gently tamp the area with your hands to fill in air pockets.

Water the tree thoroughly after planting. If it sinks after being watered, you must lever the roots up from below with a shovel and start over, replanting at the correct depth; then, firmly but gently, tamp the surrounding soil again with your hands.

Apply wood chips or bark mulch over the planting area, 2 to 4 inches deep and in a radius of at least 18 inches around the trunk—but be sure to leave a 2- to 3-inch circle of mulch-free space directly around the trunk. Your tree will grow faster if you keep the planting area clear of grass and weeds for at least three years, which will minimize root competition.

{page break}

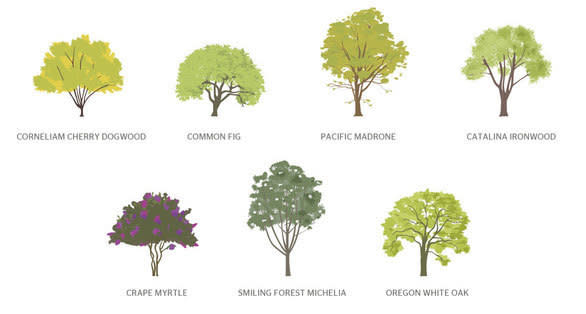

Cornelian cherry dogwood

Cornus Mas

Deciduous tree from Europe and Central Asia with bright yellow flowers blooming in late February to early March. Grows as a multi- or single-trunked tree with slightly shiny, 3-inch-long, broadly elliptical leaves and bright red fruit in July. Generally disease- and pest-resistant, it grows in sun or partial shade and tolerates poor, dry soil. ‘Golden Glory’ is a vigorous, upright cultivar reaching 25 feet tall and 15 feet wide. ‘Variegata’ is cream-variegated and smaller in stature. Cold-hardy to -30 to -20 degrees .

See it in person: There is a labeled example near the center of Laurelhurst Park (3554 SE Ankeny St).

Common fig

Ficus Carica

Native to western Asia, the fig tree is deciduous, drought-tolerant, and revels in reflected heat. Leaves are boldly lobed and the fruit is ambrosial. ‘Desert King’ (late summer fruit, richly flavored, pink flesh) and ‘Vern’s Brown Turkey’ (delicious amber fruit ripening in both summer and fall) are especially reliable in our area. Grows to 25 feet tall and wide, but can be espaliered and kept smaller when roots are confined. Cold-hardy to 10 to 15 degrees or less.

See it in person: Examples can be found throughout Portland, particularly in Southeast Portland backyards.

Pacific madrone

Arbutus Menziesii

Magnificent West Coast native broadleaf evergreen. Reaching 30 to 50 feet tall and 30 to 50 feet wide, with small, white, urn-shaped flowers in late spring followed by little orange berries that birds adore. Glossy, elliptical leaves have a blue-white cast underneath. Madrone trunks are, frankly, stunning: Cinnamon-brown bark peels off to reveal sinewy, smooth, chartreuse bark underneath. Previous year’s leaves drop in June. Need full sun to dappled shade. Good drainage is essential and, once established, the tree should receive no summer water. Cold-hardy

to 0 to 10 degrees.

See it in person: Vestigial clumps of Pacific madrone sit in the south woods at the Elk Rock Gardens (11800 SW Military Ln), on the slope below N Willamette Boulevard, and in patches along the region’s freeways.

Catalina ironwood

Lyonothamnus Floribundus Var. Asplenifolius

A small evergreen tree from Southern California’s Channel Islands with ferny, evergreen foliage and cymes of flat-topped white flowers in summer. Flowers turn brown after flowering and are retained on the tree. Bark is reddish brown and peels off in shreds. Can cope with hot sun, reflected heat, drought, and poor soil. Needs good drainage. Reaches 20 feet tall by 10 feet wide with a broad, umbrella-shaped crown. Cold-hardy to 10 to 15 degrees or less.

See it in person: A few examples can be spotted in inner Southeast Portland (like the 2500 block of SE Ash St).

Crape myrtle

Lagerstroemia Hybrids

Crape myrtles are well adapted to hot, urban areas of the Pacific. Glossy, dark green leaves come out in late spring and turn yellow, orange, or dark red in the fall. Fluffy flowers resembling crepe paper appear from summer to fall. The bark is sinewy, often exfoliating in patches to reveal a smooth, skinlike layer of underbark. They flower better with some summer water until established. My favorite, ‘Catawba’, grows up to 15 feet and has panicles of purple flowers and orange-red fall color. Cold-hardy to 0 degrees.

See it in person: Several grow in the Hoyt Arboretum Visitor’s Center (4000 SW Fairview Blvd).

Smiling forest michelia

Magnolia Maudiae

An exceptional evergreen magnolia with large, white flowers (delectably scented like lilies) that are produced in leaf axils in March and April. This Chinese native has 4- to 6-inch blue-green elliptical leaves with a chalky blue underside. It reaches 20 to 30 feet high with a variable form. Variety platypetala is more robust and taller. This tree appreciates regular summer irrigation. Cold-hardy to 17 degrees or less; grows hardier with age.

See it in person: A row stands outside of the County Cork Pub (1329 NE Fremont St).

Oregon white oak

Quercus Garryana

Our native oak, whose gnarled, lichen-draped winter branches are emblematic of the Willamette Valley horizon. This large, deciduous tree has an irregular, rounded form; leathery, deeply lobed leaves; and a glorious branching pattern as it ages. Its acorns feed wildlife. Best in low-elevation sites with well-drained soil. Tolerates seasonal flooding, but should be dry in summer. Grows to 65 feet tall and 50 feet wide. Cold-hardy to 0 to 10 degrees.

See it in person: Specimens are scattered all over the Willamette Valley.

{page break}

Staking

Studies show that trees develop best with-out staking. But sometimes staking is necessary when trees are planted in heavily trafficked areas or on windy sites where they need the support. Sink two 2-foot-by-2-foot boards, each about 3 to 5 feet tall, into the ground on opposite sides of the tree, 2 to 3 feet away from the trunk. Loosely secure the lower half of the trunk (about 2 to 3 feet above ground level is usually best) to each stake with a flexible material like chain-lock tree tie or, if you’re forgetful, biodegradable twine. The root system should remain stable, but the trunk should flex a bit to encourage the development of stabilizing roots. Remove the stake and ties within the first year, as bindings can girdle and kill a tree as it grows.

Watering

During your tree’s first three summers, it will need regular, deep watering. The amount of water you supply depends on the size of the tree’s roots: A small seedling might need a half gallon of water daily at first, while a 6-foot tree with a 2-foot diameter root ball might need 5 to 10 gallons twice a week while getting established. The best way to determine when to water is to feel the soil beneath the mulch and water if it’s dry below the surface.

Looking to the Future

Of course, you want to plant a tree that is appropriate to its setting. When nicely scaled to its environment, a healthy tree is a soothing presence, while the wrong tree in the wrong place makes you want to run for your loppers every time you see it. If your site can accommodate it, think big: Large trees provide a resting place, shelter, and a sense of permanence and solidity in a yard or garden. Also, practically speaking, the bigger the tree, the more oxygen it supplies, the more storm-water runoff it mitigates, and the more shade it provides to buildings and city streets.

While not all trees will live past the 40-year mark, there’s a certain pleasure in imagining that your long-lived tree might be cherished by a future inhabitant of your house, who will be thankful for your clever planning—and proper planting.