Burb Battle

The Willamette Shore rail line runs just behind Merty Muller’s white, low-slung house, separated from her bedroom by about 10 yards and a leafy hedge. Weekdays, the track is a lovely dog walk. In the warmer seasons, a vintage trolley trundles sightseers down the line every two hours. But if transit-savvy politicians and developers have their way, by 2017 sleek new streetcars will roll past Muller’s home several times an hour.

Surprisingly, perhaps, Muller likes the idea. The 75-year-old, a neighborhood resident since 1964, points to a little hillock where streetcars stopped in the 1920s—history she’d love to see repeated. "I think it would be wonderful to get on the trolley and go to downtown Portland," she says.

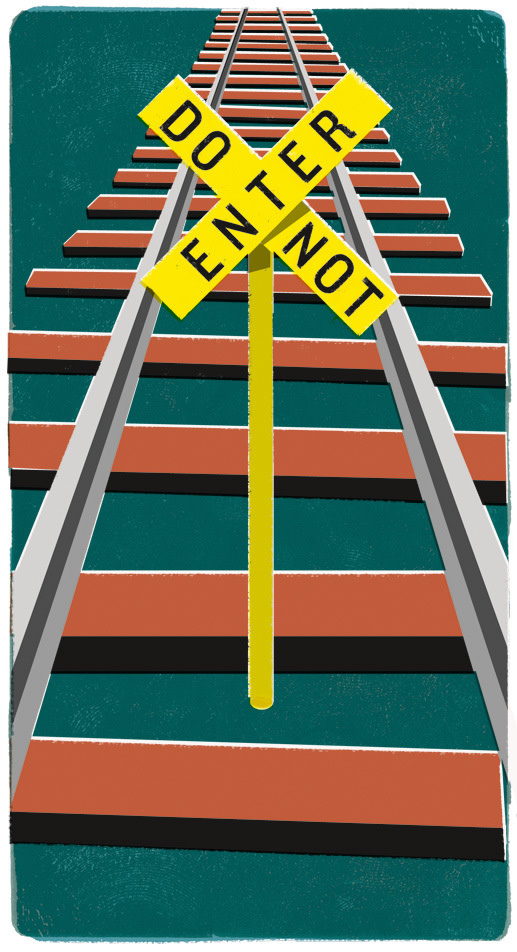

Many of her neighbors do not share her enthusiasm. These particular rails slice through Dunthorpe, the most legendarily exclusive neighborhood in Portland (or rather, unincorporated Multnomah County, as the mansion-studded enclave—home base of actor Danny Glover, the occasional Trail Blazer, and other notables—refuses to join the city). Right now, the streetcar is officially one of three options for improving transit on bustling Rte 43, along with “enhanced” bus service and doing nothing. Metro, two cities, and two counties all get a vote.

With the streetcar intimately connected to the Lake Oswego city council’s future dreams, but heavyweight Dunthorpeans hoping to stop it in its tracks, two of Portland’s ritziest suburbs appear to be headed for an old-fashioned backyard brawl.

The first jab: a new nonprofit called Keep Lake Oswego Livable emerged, with a slick website (360millionandcounting.com) that’s bristling with criticism of the streetcar plan. Dunthorpe resident Elaine Franklin—a veteran political strategist best known as former Senator Bob Packwood’s wife—is the group’s president. Her Riverwood Road neighbor Eli Morgan, founder of the billion-dollar M Financial Group, participated in its early organization. Other neighbors took aim at the planning process’s early rounds.

The group also hired savvy political consultant Leonard Bergstein. Spinning the streetcar’s opposition as a grassroots movement of friends and neighborhoods, Bergstein says, "There’s a pretty visceral feeling that this is too much to spend when we’re concerned about schools and every other budget priority."

It’s easy to understand Dunthorpeans’ alarm. The tracks run close to homes, sometimes splitting front walkways in two. Franklin—who boasts of her schoolgirl streetcar commute in her native England—argues the whole plan is misguided. "The project’s ridership and financing models rely on wishful thinking."

Earl Blumenauer originally hatched the streetcar idea 22 years ago when, as a Portland city commissioner, he cobbled together six different governments to buy the tracks and right-of-way from Southern Pacific Railroad. Federal funding programs devised by now-Congressman Blumenauer would likely help pay the $350-million-plus tab. Exactly how many of Rte 43’s 6,000 peak-hour auto trips would turn into streetcar rides is up for debate. (Not many, opponents contend.) But as Portland proved in the Pearl and South Waterfront, streetcars don’t just move people; they spur development. Lake Oswego Mayor Jack Hoffman and most of the city council want the streetcar to spark a new urban neighborhood in the burb’s industrial Foothills district. In June, Lake O signed a $1.3 million contract with Portland developers Williams/Dame & White to get the project started.

Those keeping score like to point out the director of LO’s economic and capital development department, Brant Williams, and the principals of Williams/Dame & White (no relation) all worked on Portland’s South Waterfront. "The circus is just moving south," Bergstein chimes. Or as Franklin puts it, "If you wanted to be Machiavellian about it, why does cute little upper-middle-class Lake Oswego get a cute little streetcar while other parts of the metro area don’t get their basic transit needs met?"

As the battle plays out this fall and winter, these influential tribes—or at least a bunch of chiefs—will be in full war paint. But on a quiet morning walk down the tracks with Merty Muller, the issue feels like yet another collision between the pleasant present and the uncertainties of change.

"We put together six different jurisdictions to buy this rail alignment," Muller says. "We did it for the future. Well, the future is now."