Portland's Ecotraditions

Take a swig from any of Portland’s Benson Bubblers and you can’t help but be charmed. But maybe you’re also being inspired. How else to explain Portlanders’ deep connection to their surroundings? Consider that the water gurgling up from the famed, cast-bronze fountains commissioned by philanthropist Simon Benson in 1912 travels 26 miles from one of the—if not the—most pristine urban water sources in the world: the Bull Run Watershed.

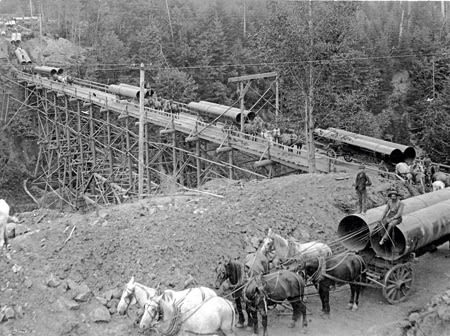

The reservoirs there are arguably Portland’s first act of “building green.” Soon after President Benjamin Harrison declared the watershed a National Forest Reserve in 1892, the city began installing dams and pipes, instantly making Portland the envy of the West Coast for the purity of its water. Bull Run (including the Bull Run Lake, pictured above), became the city’s earliest green export as crews on Pacific ships often traveled out of their way to fill up, sometimes even selling its waters at a profit overseas.

Today the reservoirs lie in a 102-square-mile conservation zone where more than 250 species of wildlife, from blue herons to black bears, enjoy the waters as comfortably as the half million people living directly to the west. Here conservation and engineering are seamlessly and poetically entwined at what stands as the beginning of Portland’s tradition of sustainable urban living. What follows is our timeline of the city’s—and the state’s—many other major milestones.

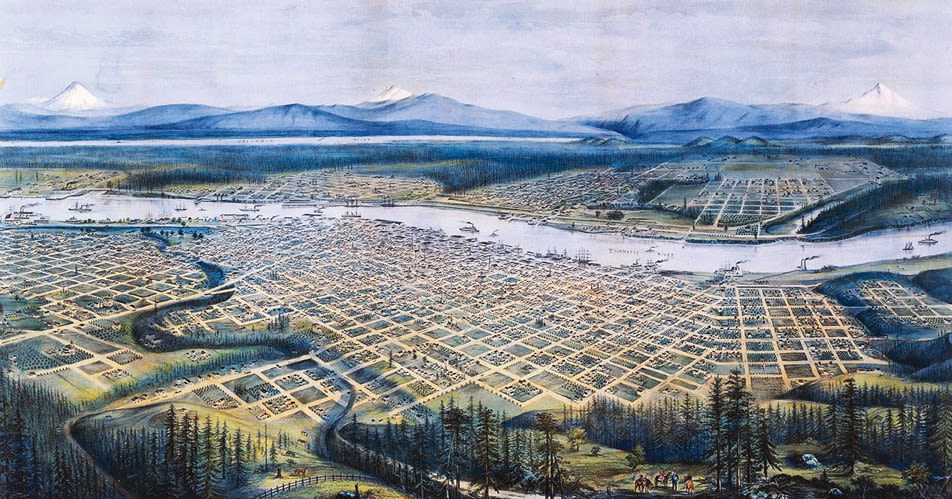

1845

It remains a mystery why Asa Lovejoy and Francis Pettygrove platted the town they would name “Portland” with tiny 200-foot blocks. But four years later, adjacent landowner Daniel Lownsdale followed their lead in his addition to downtown—with one exception: he added a string of 100-foot-by-200-foot park blocks (pictured above). Captain John Couch continued the pattern of small square blocks and narrow park blocks to the north, with his own variation: he turned his street grid off the compass points to align with the bend of the Willamette River. The result is a central city in which more than half the land area is free of buildings and every street heads to the river.

January 2, 1895

Portland savors water from the Bull Run Watershed for the first time, thanks to pipes laid down a few years before (pictured above). Health officials notice an immediate, sharp decline in typhoid fever.

1902

Birding clubs from Astoria and Portland merge to become the Oregon Audubon Society, one of the West’s earliest conservation groups. A long, effective history of Audubon advocacy begins with the club’s first president—naturalist and photographer William Finley (pictured)—whose photos of Three Arch Rocks inspire Teddy Roosevelt to turn the Oregon site into the first West Coast bird refuge in 1907.

1903

“No city,” famed parks planner John Charles Olmsted (pictured) tells Portland’s civic leaders, “can be considered properly equipped without an adequate park system.” Olmsted’s vision for a regionwide series of connected parks is largely left to gather dust (see 1981) except for one segment: Terwilliger Parkway, which the city completes. But Olmsted’s assistant, Emanuel Mische, stays on as Portland’s first parks superintendent, designing Laurelhurst Park and the Wildwood Trail in what later becomes Forest Park.

1912

To lure workers to drink fresh water instead of beer, lumber magnate Simon Benson gives the city $10,000 to install 20 bronze drinking fountains. Nicknamed “Benson Bubblers,” they bring the cool taste of Bull Run to Portland’s downtown streets.

1913

Governor Oswald West successfully sneaks a 66-word bill through the legislature to turn Oregon’s beaches (pictured above) into public highways—in effect, making them public property forevermore. Lawmakers, West later jokes, took the ploy “hook, line, and sinker.” The label “highway” is changed to “recreation area” in 1947.

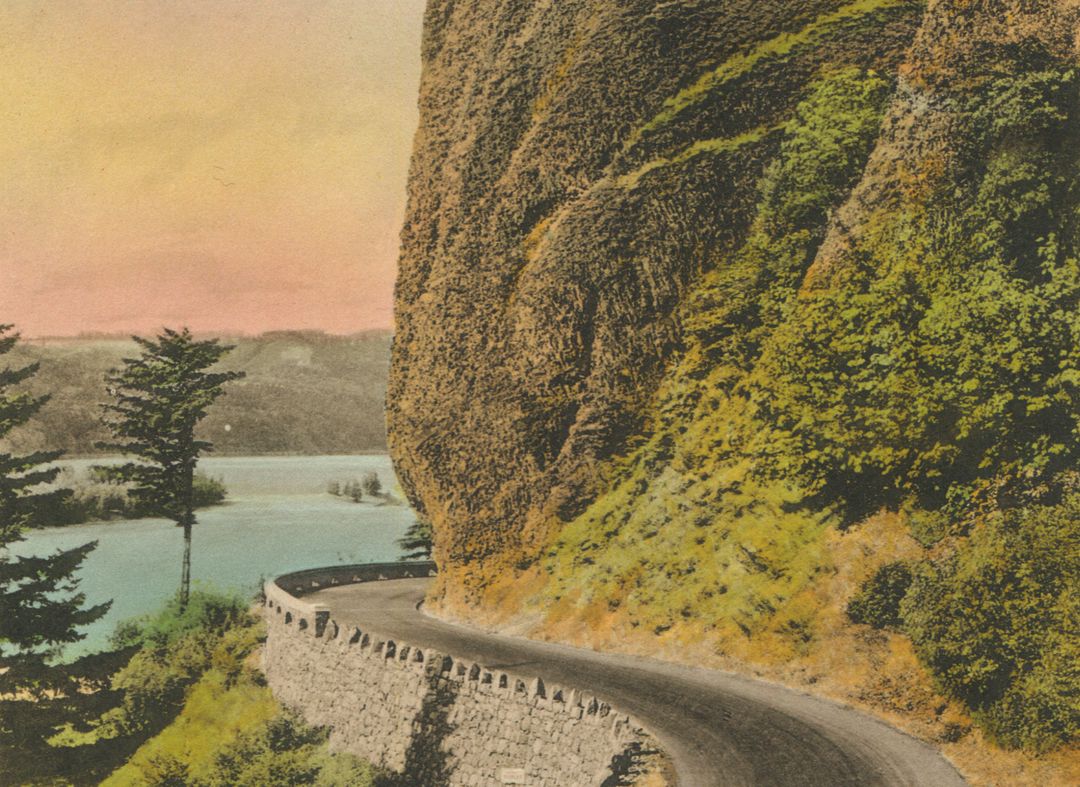

1913

Eccentric railroad magnate Samuel Hill joins forces with Multnomah County and road engineer / landscape architect Samuel Lancaster to construct what was widely regarded as one of the world’s most beautiful roads—the Columbia River Highway (pictured). “Men from all climes,” Lancaster wrote, “will wonder at [the Gorge’s] wild grandure [sic] when once it is made accessable [sic] by this great highway.”

1915

Simon Benson donates 380 acres surrounding Multnomah and Wahkeenah Falls (pictured) to the City of Portland, effectively turning two of the Columbia River Gorge’s most dramatic scenic resources into a city park.

Image: Stanley Parr Archives

1920

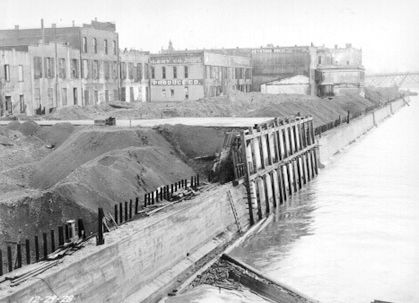

Olaf Laurgaard, a feisty Norwegian transplant and city engineer, concocts downtown’s first waterfront beautification plan, condemning 18 blocks of rotting docks—called by some “the canker sore of the westside Willamette”—and replacing them with a harbor wall (pictured above), an up-to-date sewer system, and a public esplanade. Irate dock owners delay progress for years, but the project’s 1929 completion transforms the river’s edge into a public right-of-way, making an eventual Waterfront Park possible (see 1978).

1931

Portland takes an early stand against chain stores and big-box retail. In an attempt to keep the local economy strong, the Independent Merchants Association pressures the city council to increase taxes on Piggly Wiggly (pictured above) and Safeway, blaming the stores for economic downturns. It was the first tax of its kind in the country.

Image: Stanley Parr Archives

1932

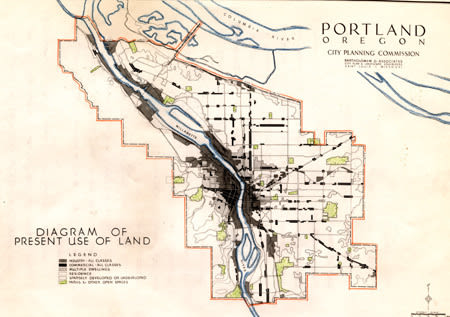

In Portland’s most far-reaching early city plan, planner Harland Bartholomew foreshadows future controls on sprawl. “The problem is not one of congestion,” he wrote, “but rather one of how much can we afford to spread out.”

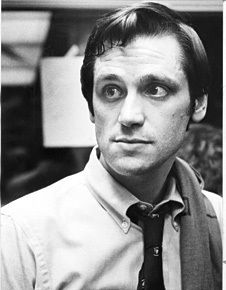

1935

Due to the traffic unleashed by the Columbia River Highway and in anticipation of the Bonneville Power Association’s damming and electrifying of the Columbia River, 25-year-old architectural wunderkind John Yeon (pictured) begins penning the Report on the Columbia Gorge. The Northwest’s first environmental impact statement, it outlines the first preservation plan for the Gorge.

1937

Yeon designs the masterful Watzek House (pictured) and, soon after, a series of the world’s first plywood houses. These help establish the Northwest style of regional architecture, while foreshadowing by four decades such “green” innovations as thermodynamic ventilation systems and double-glazed windows. Sixty-five years later, famed Australian eco-architect Glenn Murcutt sees the houses and smiles, “All I’ve ever tried to do is here.”

1938

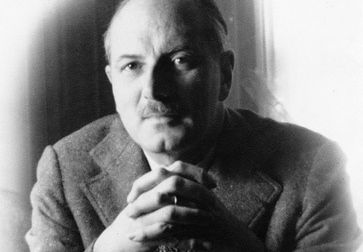

Addressing the City Club of Portland, renowned urban historian and planning advocate Lewis Mumford (pictured) offers a challenge: “I have seen nothing so tempting as a home for man and woman as the Oregon country. You have here a basis for civilization on its highest scale, and I am going to ask you a question you may not like. Are you good enough to have this country in your possession?”

1938

Portlanders—and mayors looking for publicity—lodge the city’s earliest known protest of pollution of the Willamette River (pollution pictured). In response, voters create the Oregon State Sanitary Authority (now the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality) and charge it with the responsibility of cleaning up industrial waste in the state’s rivers. Six years later, a report from Oregon State University declares that the Willamette is dead. (No oxygen registered in the river as it flowed past Portland.) The culprit? Industrial mills dumping sewage and a Sanitary Authority with no actual regulatory authority. The Willamette’s condition and the ineffectual government will later inspire Tom McCall’s documentary, Pollution in Paradise (see 1962).

1948

A citizen group called the Committee of Fifty (pictured) lobbies Portland City Council to buy and dedicate 4,200 acres around Mische’s Wildwood Trail for the creation of Forest Park.

1958

Voters authorize (narrowly) the creation of the Portland Development Commission. First project: clearing 56 city blocks for the South Auditorium Renewal Project. But among the new Modernist towers (and the ghosts of Portland’s first Jewish neighborhood), landscape architect Lawrence Halprin introduces “nature in the city” in the form of a metaphorical watershed comprised of three plazas: Lovejoy Fountain, Pettygrove Park, and Ira Keller Fountain (pictured).

1961

Jane Jacobs publishes The Death and Life of Great American Cities, ushering in a new school of urban planning. She critiques rationalist planning approaches, such as the urban renewal projects of Robert Moses, and begins a nationwide movement that embraces dense, mixed-use features to encourage community in cities. It becomes a bible for those who lead Portland’s downtown renaissance a decade later.

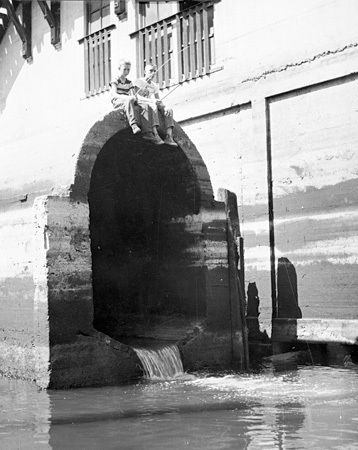

1962

Popular TV newsman Tom McCall airs the documentary Pollution in Paradise, indicting Oregon industries’ pollution of both air and water, seen here as boys fish in a sewer outflow. Against footage of pulp waste cascading into the Columbia River (broadcast as Rachel Carson’s history-changing exposé on pesticides, Silent Spring, is making headlines), McCall intones, “How far pollution marches in Oregon is a matter … of citizen responsibility, should the citizens face up to it.” Thus McCall’s image as Oregon’s environmental crusader is born, carrying the Republican to secretary of state in 1965 and governor in ’67 and ushering in Oregon’s new era of leadership in environmental stewardship.

Image: James Beard Foundation

1964

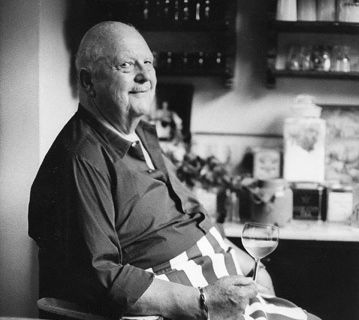

In his memoir Delights and Prejudices, James Beard (pictured), the father of American gastronomy, extols Oregon’s bounty of fresh seafood, farm goods, and berries. “No place on earth, with the exception of Paris,” he writes, “has done as much to influence my professional life.” Three decades later, his words become a mantra for the rise of Oregon cuisine.

Image: John Yeon Estate

1964

John Yeon buys a 75-acre stretch of the Columbia River’s northern shore directly across from Multnomah Falls. Over the next decade, he shapes it with bulldozer, chainsaw, and plantings into what he calls The Shire. Sculpted with a series of paths and captured views of the falls, this monumental conservaton effort is best described as an inverted English picturesque landscape, in which nature instead of architecture has become the “folly.” Upon Yeon’s death in 1994, the Shire becomes a center for Pacific Northwest landscape studies for the University of Oregon.

Image: Courtesy Daniel Coe

1966

While campaigning for governor against McCall, State Treasurer Bob Straub proposes a step beyond Olaf Laurgaard’s harbor wall (see 1920): a state-owned park along the Willamette, to be called a “greenway.” McCall wins the election but embraces the idea as his own.

1966

David Lett is the first person to plant pinot noir grapes in the Willamette Valley. Thirteen years later, the resulting wine garners top honors at the Gault-Millau French Wine Olympiades, an international competition, putting Oregon on the world’s viticulture map.

Image: Derek Hayes

1967

In March, McCall issues an executive order to clean up the Willamette and creates a committee to study the viability of a greenway. In June, the Legislature passes the Willamette River Park System Act, authorizing $800,000 for the State Highway Commission (now the Oregon Department of Transportation) to obtain land along the Willamette River for future recreational purposes.

1967

A Cannon Beach motel owner erects a driftwood fence, creating Oregon’s first private beach. Governor McCall quickly steps in (pictured). We must “protect the dry sands from the encroachment of crass commercialism,” he claims. The Beach Bill, McCall’s first major legislative victory, is signed into law on July 6 to protect public ownership of beaches, anchoring Oregon’s tradition of a communitarian outlook on its land.

1968

Tired of picking up trash on his hikes, outdoorsman Richard Chambers, inspired by an article about a similar Canadian initiative, hatches an idea for container deposit legislation. He immediately begins writing letters to Oregon lawmakers.

1968

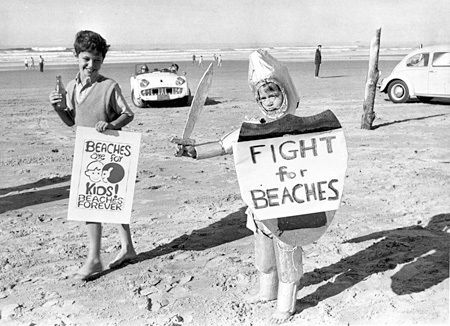

More than 200 people rally on Cannon Beach (pictured) in support of a proposed gas tax that would authorize the state to buy privately owned beach land. The volunteer group Beaches Forever partners with then-State Treasurer Straub to get the measure voted into law. Debate surrounds the Beach Bill’s guidelines, and it won’t be until 1969, when the Legislature passes an additional measure, that the language is clear enough to stand up in court when challenged by private developers.

1969

Thanks to the auto boom, use of public transit declined steadily through the 1950s and ’60s, causing Portland’s primary transit source, Rose City Transit, to flirt with bankruptcy and threaten to hike fares and terminate services. Portland City Council resolves to create the Tri-County Metropolitan Transportation District of Oregon, or TriMet, to take over Rose City’s operations and reverse the deterioration of the public transit system.

Image: Andy Anderson

August 19, 1969

As the wrecking ball sets to blast the old Oregon Journal building, the activist group Riverfront for People organizes a picnic for 350 people on a nearby patch of grass to call for a riverfront park. One picnicker asks, “Why don’t we give downtown Portland some breathing space?”

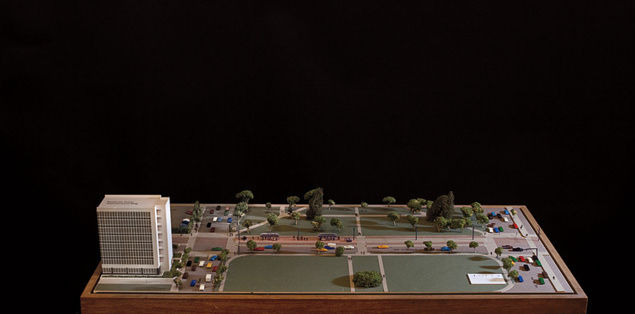

January 17, 1970

Inspired by a sketch of a new public square, the Portland Planning Commission rejects Meier & Frank’s request to build a twelve-story parking garage downtown atop their two-story structure (pictured). Retailers fume, and the march to create Pioneer Courthouse Square begins.

1970

Voters remind the government to clean up and protect the state’s rivers by passing the Oregon Scenic Waterways Act. The act dictates that one must notify the government and receive approval before commencing activities that fall within a quarter mile of the riverbank—such as chopping down trees or implementing construction—on every river from the Columbia to the Klamath.

Image: The Oregon Historical Society and Gerry Lewin

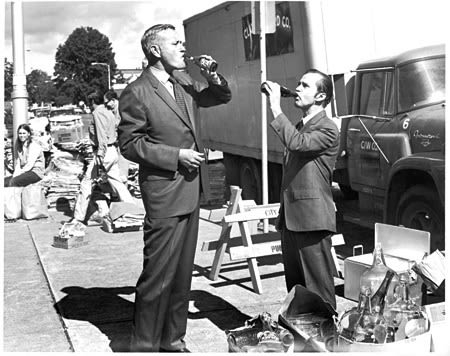

1971

McCall (pictured) joins Chambers’s fight to “put a price on the head of every beer and pop can and bottle in the United States.” Despite frantic opposition from the soft-drink and bottling industries, the bill passes, becoming the first container deposit legislation in the United States.

1971

Twenty-three-year-old freshman legislator Earl Blumenauer dreams up and builds the coalition to pass the Bike Bill, requiring bicycle and pedestrian improvements on all transportation projects that receive funding from the state. The federal government follows Blumenauer’s lead—two decades later—with the 1991 Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act.

1972

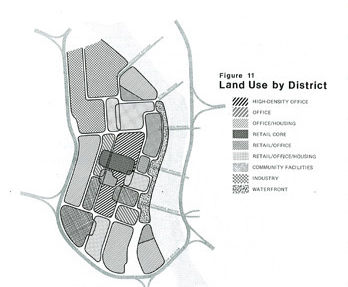

The city council adopts the Downtown Plan. Unlike past Portland plans designed by visiting consultants, this one is shaped entirely by locals: business owners, planners, architects, citizens, and politicians. It provides a blueprint for Mayor Neil Goldschmidt to reinvent the central city with new auto-free zones, public space, and a connection to the river.

1973

After years of trying to achieve state oversight of land use, McCall finds two allies: Hector MacPherson, a dairy farmer and Republican state senator; and Ted Hallock, a liberal state senator. With a plan drafted by landscape architect Lawrence Halprin, McCall barnstorms the state, warning of the coming “sagebrush subdivisions, coastal condomania, and the ravenous rampages of suburbia.” The result: Senate Bill 100, the most comprehensive state land regulation ever passed in the United States.

Image: Sam Beebe

1973

The Willamette River Park System Act becomes the Willamette River Greenway Act, a law that places the greenway under the protections of Senate Bill 100. Two years later, the state adds number 15 to the original 14 commandments of state land use: protecting around 200 river miles from uncontrolled development, from the base of the Cascade Range near Eugene to its confluence with the Columbia River.

Image: Jef Jaisun

1974

Three important environmental groups surface—Portland Sun, Rain, and Regional Tilth (pictured). Portland Sun promotes early solar technologies. Rain starts a community resource center where folks can learn methods for living simply. And the Willamette Valley chapter of Tilth begins an organic certification program whose standards are later adopted by the National Organic Program.

Image: Gwoeii1974

Mayor Neil Goldschmidt joins forces with Multnomah County Commissioners Don Clark and Mel Gordon to build a light-rail line to Gresham rather than a freeway to Mount Hood.

1974

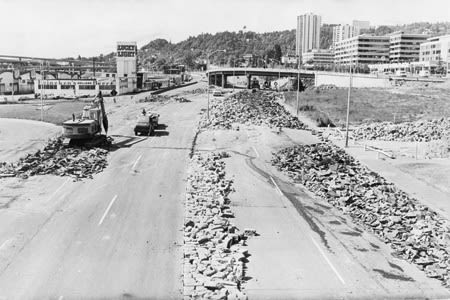

Riverfront for People’s picnic turns into a jackhammer party to tear up Harbor Drive for Waterfront Park.

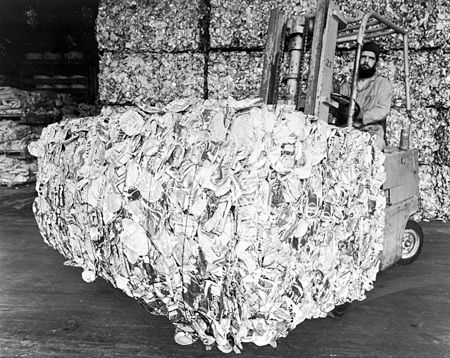

1974

The Portland Recycling Team, a student-led effort formed at Portland State University in 1970, evolves into Portland’s first curbside recycling businesses, Sunflower and Cloudburst (pictured).

Image: Cynthia Woodyard

1975

Former Governor McCall and Henry Richmond form the watchdog group 1000 Friends of Oregon to sue cities who don’t complete a comprehensive land-use plan as mandated by Senate Bill 100.

1975

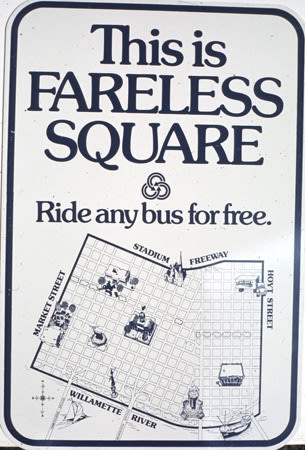

Goldschmidt leads the Portland City Council to enact a “parking lid” while TriMet creates Fareless Square to discourage short car trips.

Image: Community Garden Program

1975

Neighborhood associations lobby Portland City Council to pick three sites for a new Community Garden program (pictured) that will provide 450 city dwellers with space to grow their own food. Today, the program has 32 sites for more than 3,000 people—in 2008 alone, the waiting list doubled to 1,300, leaving the program in search of more space.

1975

The Environmental Protection Agency labels Portland the nation’s most livable city, ranking it high in every category—economics, politics, society, environment, and health/education.

1977

The Transit Mall opens, centralizing every bus route in the region’s transit system onto two car-free streets in downtown Portland.

Image: Metro

1978

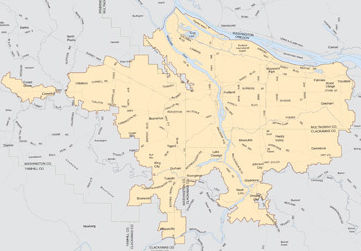

A multigovernment committee and the region’s garbage authority merge to create Metro, the only directly elected regional government in the country. Its first major task: adopting the urban growth boundary mandated by Senate Bill 100.

1978

Waterfront Park opens to the public and is quickly nicknamed “*Portland’s Front Yard*”—and officially renamed Gov. Tom McCall Waterfront Park in 1984.

1979

The Arab oil embargo inspires Portland to become the first US city to adopt a local energy policy, establishing an Energy Office and a citizen Energy Commission to monitor the city’s energy use and educate members of the public about how to weatherize their homes. Five years earlier, Oregon drew the nation’s attention to its environmental ethos by replacing Governor Tom McCall’s Lincoln Continental with a smaller, fuel-saving economy car (pictured).

Image: Cross & Dimmitt

1979

John Yeon hosts an evening picnic and invites hiker and self-described “housewife” Nancy Russell. Inspired by the walks, the views of Multnomah Falls, and the rising full moon that Yeon carefully chose the date for, the housewife turns activist and co-founds the Friends of the Columbia River Gorge a year later.

Image: Jonathan Jelen

1981

The 40-Mile Loop Land Trust incorporates to acquire rights-of-way for a regionwide trail system. Urban naturalist Mike Houck notices that the proposed loop nearly matches John Charles Olmsted’s vision of 78 years earlier (see 1903). The trail system now has more than 140 miles of trails and 30 interconnected parks winding throughout all of Multnomah County.

Image: Stanley Parr Archives

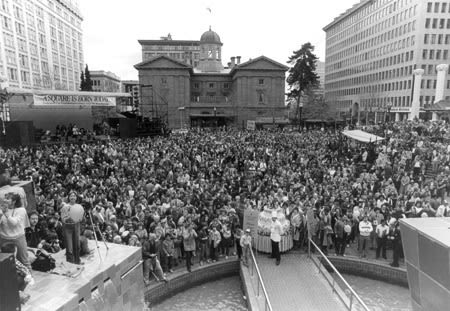

1984

One of the dreams of the 1972 Downtown Plan, Pioneer Courthouse Square opens, becoming Portland’s “Living Room” and its most popular landmark (9.5 million visitors a year). In 2008, it is named one of America’s 10 Great Public Spaces by the American Planning Association.

1984

A group of architects publishes a report called “Last Place in the Downtown Plan,” outlining their vision for the area bounded by W Burnside Street, the Willamette River, and I-405 to become a thriving mixed-use neighborhood. The first step: creating the Northwest 13th Avenue Historic District, which becomes the first seed of the Pearl District.

Image: Susan Seubert

1986

Nancy Russell creates what she adroitly calls a “parade” of Columbia Gorge supporters that United States Senator Mark Hatfield “wants to jump in front of.” Led by Hatfield, Congress enacts the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area, fulfilling Yeon and Mumford’s half-century-old vision (see 1935 and ’38).

Image: Trimet

September 5, 1986

After four years of construction, MAX light-rail service begins, the first leg 15 miles of what by 2010 will be 52 miles of lines. Two hundred thousand citizens ride the first weekend.

Image: Mike Houck

1988

Mike Houck carries on the Audubon Society of Portland’s 86-year tradition of advocacy (see 1902) by successfully establishing Oaks Bottom Wildlife Refuge (pictured), a 140-acre wetland, as Portland’s first official urban wildlife refuge.

January 25, 1989

Led by City Commissioner Earl Blumenauer, Portland City Council votes to ban the use of polystyrene foam by city restaurants and food vendors.

1990

After seeing the group’s poster on the Broadway Bridge, Rex Burkholder attends a meeting of the Portland Bicycle Cooperative and leads it to become the Bicycle Transportation Alliance, one of the region’s most effective lobbying forces. The Alliance launches Burkholder to a seat on Metro, and signifies the institutionalized activism that will shape the city’s next era.

1991

Addressing one of Portland’s oldest problems—and one that Laurgaard had attempted to fix—the Northwest Environmental Advocates bring a lawsuit against the city for allowing sewage to spew into the Willamette and Columbia. It results in the city’s largest infrastructure project ever—the $1.4 billion “Big Pipe” combined sewer overflow system—and a mandated commitment to prevent sewage from overflowing into local rivers and streams.

1991

The Legislature passes the Oregon Recycling Act, setting a statewide goal of 50 percent recovery by 2000 and requiring cities to increase their recycling services. A year later, Portland follows suit by making residential curbside service available to all residents.

Image: Aleph Studio

1991

Senate Bill 100’s tentacles continue to grow with the adoption of Oregon’s Transportation Planning Rule, mandating reductions in automobile miles traveled per capita and requiring cities to adopt zoning to promote pedestrian travel.

Image: Craig Mosbaek

1992

To enable farmers to sell directly to customers, Craig Mosbaek, Ted Snider, and Rick Hagan gather 13 vendors at Albers Mill to start the first of four farmers markets in Portland.

Image: Greg Acker

1992

The Sustainable Building Collaborative builds the HERE Today House (interior pictured), Portland’s first green demonstration home. The New York Times asks: “Is it the house of the future?”

Image: Mark Gamba

1992

Metro adopts a Metropolitan Greenspaces Master Plan to protect natural areas; preserve plant and animal life; establish an interconnected system of trails, greenways, and wildlife corridors; and restore open greenspaces to neighborhoods.

1993

Portland becomes the first local government in the United States to adopt the Kyoto Protocol, creating its own action plan to reduce carbon dioxide emissions.

1993

The Northwest Earth Institute opens, bringing sustainable business models and courses to over 80,000 participants.

Image: William Anthony

1994

More than 60 nonprofit environmental and social equity groups band together to form the Coalition for a Livable Future, which promotes healthy and sustainable communities.

1994

In a single year, two restaurants focused on Oregon’s local crops – Higgins and Wildwood —open, turning the Oregon bounty savored a generation before by James Beard into a culinary movement and spurring a local food renaissance.

Image: New Seasons

1994

The city council adopts the Sustainable City Principles for Portland and creates the Sustainable Portland Commission, a citizen advisory group, “to protect the natural beauty and diversity of Portland for future generations.”

1995

Metro launches the 2040 Concept, a 50-year regional planning process involving thousands of citizens. The result: a blueprint for regional and town centers connected by transit corridors, along with the preservation of thousands of acres of parks and natural habitat such as wetlands and streams. Voters pass a $135.6 million bond measure to purchase over 7,877 acres for parks, open space, and watersheds over the next seven years.

1996

The nonprofit Friends of Trees begins its Seed the Future campaign to plant 157,000 trees by 2001.

1996

The City of Portland enlists cyclists to draft the Bicycle Master Plan, a blueprint for more than 200 miles of bikeways, end-of-trip facilities, links to transit, and educational efforts.

1996

The city council establishes a mandatory commercial recycling program requiring businesses to recycle 50 percent of their waste.

1998

To encourage walking trips, the Portland Pedestrian Master Plan outlines a 20-year framework for pedestrian improvements to the city.

1998

Portland applies the Bottle Bill ethos to forsaken industrial land as Homer Williams, Joe Weston, John Carroll, and other developers partner with the Portland Development Commission to transform downtown’s polluted former railroad lands and warehouses into the streetcar- and park-laced neighborhood of condos, offices, and parks known as the River District (later the Pearl District).

1998

The Bureau of Environmental Services starts its ecoroof program with an installation atop the Hamilton Building. Grants for builders become available 10 years later with the kickoff of the “Grey to Green” initiative (see 2008).

Image: Mario's

1998

Oregon’s Department of Environmental Quality and the Portland Department of Transportation sponsor CarSharing Portland, the first car-sharing program in the country. In a few years it becomes Flexcar, and later merges with Zipcar in 2007.

Image: Ryan Moore

1999

Recalling Olmsted’s master plan (see 1903), Portland Parks & Recreation staff, along with thousands of residents, begin to develop the Parks 2020 Vision. Its goals include acquiring 1,870 acres of park land, creating public plazas and “green connections,” and establishing Portland as “the walking city of the West.”

2000

Oso Martin extends the Bottle Bill ethos to computers, founding a collective called Free Geek to recycle hardware and provide low- and no-cost technology to individuals and nonprofit organizations worldwide. Now in eight cities, Free Geek estimates it has refurbished over 15,000 computers.

2000

Portland creates the nation’s first Office of Sustainable Development (now the Bureau of Planning and Sustainability) and unveils its Green Building Program to provide financial incentives for sustainable building technologies. The city becomes one of the first to require taxpayer-built and -subsidized buildings to meet the US Green Building Council’s Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) standards.

Image: Gerding Edlen

2000

Gerding Edlen Development begins transforming the old Blitz Weinhard Brewery into the Brewery Blocks, transforming five moribund downtown blocks into the city’s most successful mixed-use development. All six buildings and renovations are LEED-rated, launching Gerding Edlen as the nation’s premier sustainable developer.

2000

Led by Planning Director Gil Kelley, Portland embarks on a ‘River Renaissance’ initiative. It begins with community workshops asking over a thousand citizens to envision the Willamette River (pictured) of the future. One year later, the city council grants its endorsement, uniting eight city bureaus in an effort to clean up the river, create a working harbor, and keep the waterfront livable, accessible, beautiful, and economically sound.

2001

Portland pioneers the first Green Investment Fund, a city grant program to offset the costs of adventuresome new sustainable-building techniques and technologies.

Image: Ecotrust

2001

Ecotrust applies the Bottle Bill ethos to architecture, developing the nation’s first LEED-rated historic renovation in the country, the Jean Vollum Natural Capital Center (pictured). It quickly becomes the city’s hub of sustainable business and government.

Image: Portland Streetcar Inc.

2001

The first new streetcar line to be built in the United States in 50 years begins serving downtown Portland. More than $1 billion in development rises along the eight-mile line.

May 2001

The Eastbank Esplanade opens. Critics call it a $30 million jogging path. Advocates see it as the first step toward transforming the east bank of the Willamette into an extension of downtown and emphasizing the river as the heart of the city. The citizens vote—with candles and with their feet—by turning the esplanade into a living circle of light on the weekend after 9/11.

2004

Portland meets the Kyoto Protocol, with greenhouse gas emissions calculated at only 1 percent above 1990 levels, an achievement largely attributed to the urban growth boundary’s check on the region’s vehicle miles traveled per capita.

Image: Kurt Hettle

2005

In what may be an indicator of future residential services, the Office of Sustainable Development creates Portland Composts!, a voluntary program that allows commercial customers to separate their food waste for compost and soil amendment. Over 375 businesses participate.

2006

Voters pass a second regional open spaces bond, unleashing an additional $227.4 million for more parks and open space across the state.

2006

A 3,000-foot aerial tram line links landlocked Oregon Health & Science University to the land-rich North Macadam industrial area. The result: the South Waterfront District —the city’s boldest, riskiest redevelopment ever. The add-water-and-stir neighborhood is a 20-year vision for the city’s densest collection of jobs, housing, green buildings, and streets, all next to its most fish-friendly stretch of river.

Image: MaxyM

2006

In response to public interest, the city council forms the Peak Oil Task Force, a citizen advisory group charged with developing recommendations for Portland should it face a decline in oil and natural gas supplies. Their 2007 report advises the city to reduce oil consumption by 50 percent over the next 25 years and prepare emergency plans for sudden and severe shortages.

Image: Amy Martin

2007

The city council gets even more aggressive with the existing climate-protection plan when it directs bureaus to reduce carbon emissions levels to 80 percent below 1990 levels by 2050.

2008

With bicycle commuters rolling along at a percentage eight times the national average, Portland becomes the largest city in history to earn the League of American Bicyclists’ platinum designation.

April 16, 2008

City Commissioner Sam Adams launches “Grey to Green” which adds an 11-cent monthly surcharge to residents’ sewer bills to generate $50 million over five years. The money will be used to plant 83,000 trees, create 43 acres of ecoroofs, launch 920 green street projects, and restore key habitat areas.

2008

Northeast Portland sees Helensview become city’s first affordable housing community to receive LEED Neighborhood Development certification.

2009

Portland State University implements a new $25 million grant to support research initiatives in sustainability university-wide. Mayor Sam Adams creates the Portland + Oregon Sustainability Institute to better synthesize business, academic, nonprofit, and government initiatives in hopes of assuring Portland’s continued national leadership in sustainable urban and economic development.