Ada Louise Huxtable, RIP

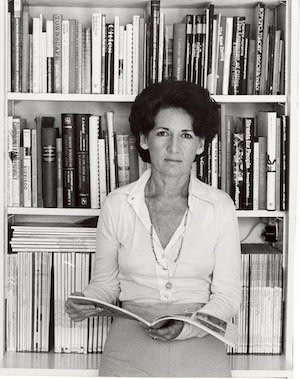

Ada Louise Huxtable in a photo from the 1960s, the decade she began her illustrious career at the New York Times as its first architecture critic.

Ada Louise Huxtable died January 7, 2013, at the age of 91. For decades she was a pioneering and influential architectural critic, writing for the New York Times from 1963 to 1982, and, after retiring from the Times, for the Wall Street Journal and other outlets up until just weeks before her death. She received prizes (the first Pulitzer ever given for criticism was hers) and influenced generations of architects, critics and anyone else who cared about buildings and the cities they create.

What was happening when she began her tenure at the Times, nearly half a century ago? The paper didn’t have an architecture critic – dance, art, music, film were considered, but not the built environment. Evidently, Huxtable suggested to the editors that they were “missing” stories on architecture; they agreed, and hired her into a new position (according to the January 12, 2013 New Republic article by that magazine's architecture critic, Sarah Williams Goldhagen).

Huxtable started at the Times in an era of early historic preservation, of mature, bland, American corporate modernism, of "urban renewal" as a way to revive dying downtowns, and highway construction to spread suburbs. Robert Moses had carved wide swaths for the auto across New York City. Jane Jacobs had published The Death and Life of Great American Cities in 1961 and helped to stop that carving. Into this mix Huxtable poured her knowledge, observations, and crisp way with words.

In 1960, Grand Central Station had been threatened with a plan by its owners to turn the upper portions of the lofty waiting room into a three-floor bowling alley (to be called Grand Central Bowl – who knew that our Central Eastside bowling alley had such an unbuilt precedent?). That plan failed – Grand Central had actually been landmarked in 1954, in response to a plan to tear it down and build an office tower in its place – but in 1965 the station owners came up with another design for a tower over the station; the Pan Am tower (now called the MetLife Building, and designed by Pietro Belluschi, with Walter Gropius and Emery Roth & Sons) had been completed just north of Grand Central in 1963.

People like Huxtable and preservationists including Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis with the Municipal Art Society fought against the new skyscraper, but the station owners fought back. Eventually the case went to the Supreme Court. The decision, in 1978, resulted in strengthening landmarks laws for historic buildings as creating public benefit.

I digress here in discussing Huxtable's critical legacy, but that's what happens when one looks back at almost any of her writing: we get pulled into a fascinating black hole of time, place and architecture, in New York and beyond. Her latest cause was a reasoned but impassioned questioning of the Norman Foster plan for New York City's main public library, another Beaux-Arts masterpiece being threatened by its owners in their quest for some real estate development income.

The issues never change, it would seem. The styles and technologies do, and she weighed in on the buildings she saw and thought were important – including Michael Graves's Portland Building just as it was being completed. She complemented Graves on his drawings of that period (they were on exhibit at the Max Protech Gallery in New York when she wrote the essay in 1979), but said that "something happens in the translation from the picture plane to the real world, and the executed works simply do not read the same way that they do on paper; the intriguing aesthetic intelligence can turn into an architecture that is fussy, flat, obvious or obscure." Additionally, the Portland Building, she noted, had been marred by "crippling economies" which made it "less than a perfect exemplar of Graves's intentions." Decades later, most of us will echo that sentiment. We're lucky she took the time to observe so many buildings and their places in so many cities.