How I Built My Home

Image: Randy Gragg

“Some art impresses you,” a painter friend of mine likes to say. “But some art empowers you.” The same goes with architecture. And so, when I first laid eyes on the Box & One, developer/designer Kevin Cavenaugh’s cinder-block apartment-retail combo at SE 28th Avenue and Ankeny Street, home to a bakery and a brewery, I thought to myself, “I can do that.”

Kevin did nothing to discourage me. A pied piper incarnate, he has the developer’s singular ability to see a trail where most people see a rock face. Kevin gave me a lesson on his handy-dandy Excel spreadsheet that computes a building’s costs and profits or losses, plus a tip on a soon-to-be-selling empty lot. Suddenly I—a journalist whose only building experience had been swinging a hammer on a friend’s house 30 years ago—was poised to become a developer.

One small, but important, detail: for 15 years, I wrote about architecture, often as a critic. In other words, building a house—glass or not—would invite the return of every stone I had ever cast at the various architects, builders, and developers I’d written about.

But beyond proving that those who write can also do, my building would be part retirement plan: build a flat for myself atop a couple of apartments; over time, the rents below would cover my mortgage. Kevin’s Excel sheet said so. But as he walked me through the intricacies of how he built the Box & One for less than $100/square foot, he added with a sideways smile, “It might cost a little more to make it as good as, well, you would want it.”

Nine years later, on the fourth try, I finally moved into my new building.

There are many traditions in architecture: developing dozens of dazzling schemes before building the one you can afford; client, architect, and contractor raging at each other; loathing city bureaucrats and their picayune rules and fees; going way over budget. I’d like to report, I became a worthy keeper of every one.

Image: Rick Potesto

In 2004, I began designing with a good friend, a visionary architect, but of a more theoretical bent. We conjured an insulated-concrete tilt-up tower with floor plates made of premanufactured bridge girders. Too expensive. We developed a breathtaking scheme to be built in Indonesian factories that make prefab homes out of sustainably harvested hardwoods. Too risky. I switched to a more practically minded team of architects who designed a suite of studies—four- and five-plexes—to better meet the goal of living atop my mortgage payment. But by 2008, construction inflation was often soaring 10 percent a month, well above what Portland rents could then pay for. I gave up. Luckily. In the coming crash, my little building would have bankrupted me.

My ultimate scheme emerged three years later from a realization that the Great Recession had brought construction pricing closer to my meager budget. It was now or never. I watched a longtime friend, the architect Rick Potestio, design a 2,160-square-foot live/work space for his artist cousin for just $240,000. It was functional, affordable, and elegant. On a bike ride with Rick, I ventured an idea: What could we build for twice that? What if we kept it really simple? What if we built a cube?

Architecture might be about ideas, but building is about collaboration. From his appetite for wine to his shoulder-heaving laugh—befitting an opera singer—Rick Potestio is Italian (a professional Italian, the noted local architect Robert Frasca once dubbed him). My builder, Greg Capen, proudly boasts he is a Texas Jew, a compound identity that wrestled like a steer handler in negotiations, but in an argument could make you feel like you had forgotten your mom’s birthday.

To this combustible mix, I brought my own overflowing baggage. I’m a mutt, one generation removed from cowpokes, bootleggers, and trailer-park dwellers (BTW: single-wide). Adopted at birth, I learned my dad’s inflexibility plus my mom’s reflexive urge to argue about everything. Add in 30 years as an art and architecture critic on a journalist’s salary. Result: high taste, sparse funds, and little interest in compromise.

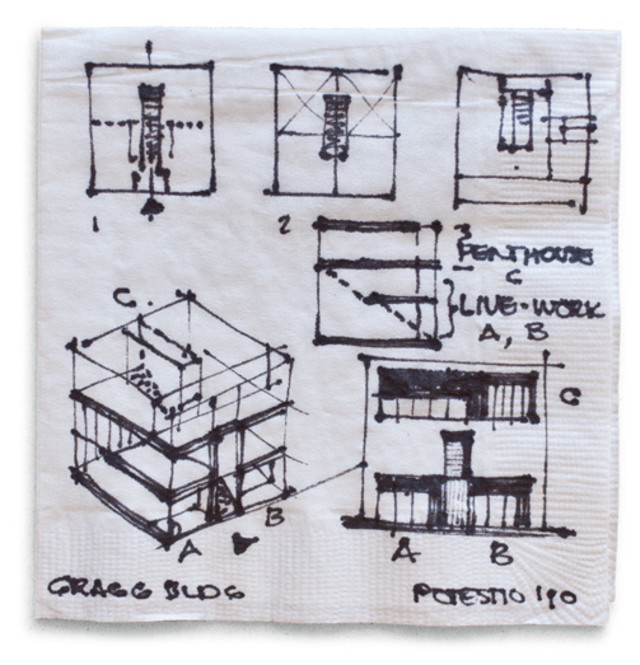

Over a bottle of wine, Rick conjured a cube on a cocktail napkin: a concrete-block box with two double-height town houses, each with a sleeping loft. A stairwell between them would lead to my third-floor flat. True to Rick’s Italian roots, it was in the palazzo style, with my floor as the piano nobile.

To assuage my native Nevadan propensity for seasonal affective disorder, big windows would abound. The main question: where? I wanted them to fill the room with light but not fade my artworks and shelves of books. Rick wanted the windows, floor to ceiling, on every corner in a classic “pinwheel” pattern of walls and openings. “Get more durable art,” he cheerily suggested. “Just get rid of the books.” As Greg’s first estimates rolled in, $130,000 over budget, we nixed many hopes: radiant-heat floors, FSC-certified wood, a steel stairwell—but not my big windows. Out went the cube, even—at least as a pure, concrete-block chunk o’ building. The top floor became cheaper-to-build wood. Rick wanted cedar for a “tight” look. To me, that reeked of Dwell magazine clichés (while too closely resembling the new apartments down the street). I proposed thick planks of recycled Doug fir that I would scorch in the Japanese shou-sugi-ban style.

Rick got his corner windows. I began spending weekends torching wood.

We slashed, chiseled, and gnawed the budget down to $451,000. But then I learned the difference between a “conceptual price” and a “bid.” Conceptual pricing is an act of imagination: the masons, framers, plumbers, and all the other subcontractors each dreaming of simple, fast construction. A bid, by contrast, is the price for which they actually will work, considering all the details—say, the complications of a slightly sloped roof over a level ceiling, or that the manufacturer would send some of the windows unassembled.

Many individual line items drove my final budget beyond $600,000. But there’s only one I hold a grudge about. The friendly bureaucrats in the city’s development review office initially estimated my building permits and fees at $15,000 per unit, or about $45,000. The final tally: $63,939.77. The $15,384 paid to fund city parks warmed my heart with images of healthy, scampering children. The $11,310 paid to the Bureau of Environmental Services will buy a nice bioswale somewhere. But the $4,030 I paid for the six-stage review of the drawings for my required new sidewalks made me want to hoist pitchfork and torch and storm city hall. (Keep in mind, the actual sidewalks cost only $11,000 to build.) One morning, as I rode my bike to the stage-five review of these drawings—during which our inspector told us to change our fonts—I saw a city crew redoing the corners of every sidewalk three blocks away from my triplex. “Might I see your drawings?” I asked the foreman. “Never use ’em,” he replied. “We just build to the usual standards.”

On May 1, 2013—18 months after my planned six-month construction schedule commenced—I slept in my new flat for the first time. Plastic sheets still covered the floors. Empty holes awaited kitchen appliances. All my possessions sat stacked beneath a tarp in one room. But when the morning sun bounced down the stairwell from the roof garden to awaken me, I arose, stumbled over a paint can, and, for the first time, really discovered the architecture.

I quipped to friends during those first few days that I was living in a James Turrell installation, the changing shapes and qualities of light were so mesmerizing. The sun beaming through the upper windows of the lower apartments’ double-height front rooms imbued the spaces with an ancient feel. My own flat unfolded in a series of captured views, Rick’s beloved corner windows seamlessly expanding my modest 1,250 square feet into the surrounding landscape. From the street, the building has a muscular presence that seems to invite both long looks and a lot of debate from passersby. One morning I looked down to see one of the city’s most prominent architects creeping by in his huge BMW. As Kevin Cavenaugh and his wife, Beth, walked around at my first dinner party, Beth added a welcome new term to my architectural lexicon: “yummy.”

I made a lot of mistakes. I thought a triplex was just a bigger house. These days, it’s a complex commercial building. Exhibit 1: the $767 per year water bill I pay just to maintain my fire sprinklers—no water yet used. And my naive failure to hire a mechanical engineer resulted in greater energy consumption than I’d hoped for—though the 4.5-kilowatt solar array I added to the roof last spring has, so far, sent electricity back to the grid more months than not.

Every contractor is only as good as his subcontractors. The slight crookedness of my roll shades reveal one flub: few window openings are square. If the sun hits certain walls right, you can see sloppy finishing the drywallers left and the painters couldn’t cover up. But the simplicity and clarity of the architecture renders minor flaws mute. The finish carpenters did beautifully, particularly on the thick, recycled-plank stairs to my roof. The tile setter flawlessly installed the complicated pattern I conjured with remaindered tile I bought for $50. The siding crew masterfully installed the burned-wood rainscreen, giving it the perfect balance of rigor and rusticity.

And how will the “glass house” hold up against all those stones I once cast? Let ’em fly. For all the overruns of my self-imposed (if poorly policed) budget, the triplex cost me about $160/square foot. The rents won’t be covering my costs anytime soon. As we negotiated and occasionally bickered, Greg often retorted: “You want a custom house for a builder’s budget.” With my newly sharpened eye for flaws big and small in new buildings I walk through, I begrudgingly admit he’s right. Yet, for all the rough conversations, client, architect, and contractor remain friends. We built something unique that strives for the spirit of the neighborhood and the city. It may not be impressive, but hopefully it’s empowering.