Why One Portland Architect Makes Models of Houses AFTER He Builds Them

Image: David Papazian

Lots of architects begin their designs with models. Last year, Ben Waechter tried an experiment: He made his models at the end of the process. It was a way, he says, to raise his eyes from the consuming challenges, compromises, and endless details of making an actual building, and weigh the success of his intentions with the clarity of hindsight. If most models serve as prototypes, Waechter’s process yields a kind of “retrotype”—in more ways than one.

“Computer rendering,” he says of today’s design lingua franca, “is always from one direction: a perspective. It’s on a flat screen; you can’t touch it. A model in space is different: it’s the real thing.”

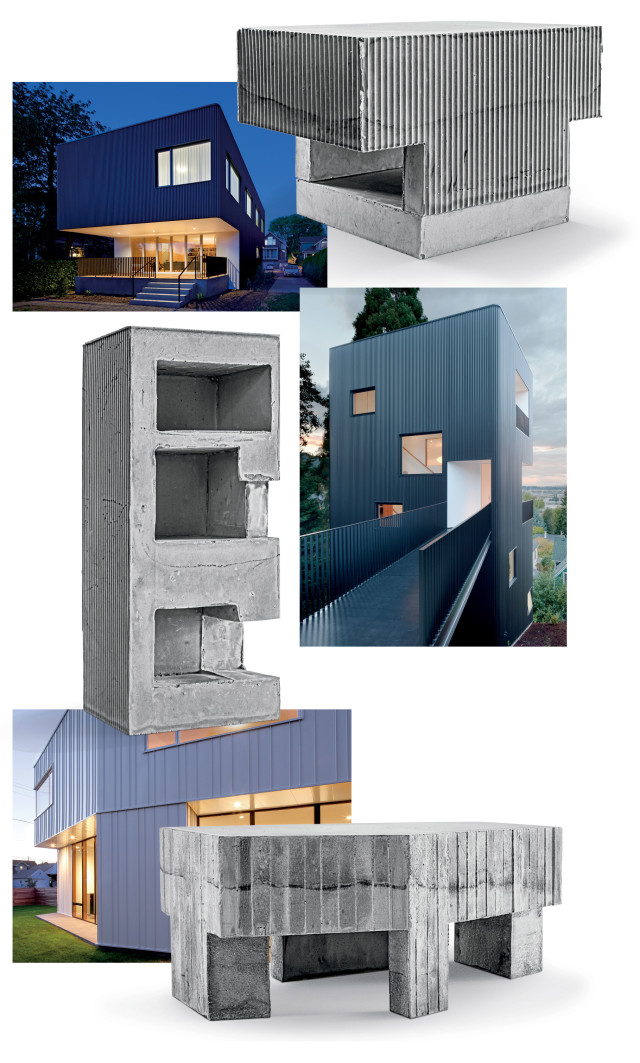

FROM TOP: Contrasted concepts and photographs for Ben Waechter’s Oakley House, Tower House, and Pavilion House

The real thing? Pondering shadows on the cave wall, Plato himself might debate that point. But Waechter’s models, collected in his brick-walled Northwest Industrial studio, stand like a small, elegant city of ideals. An alumnus of global architectural powerhouse (and prolific model builders) Renzo Piano Building Workshop and of Portland’s own star firm Allied Works, Waechter is one of the city’s most conceptually inclined architects. Often serving as his own developer and contractor, he built such noted residences as the Z-Haus, a narrow-lot duplex shaped from six identically sized rooms spiraling upward, and the Tower House, a four-story house rising from a steep lot. In Eugene, he designed the stylish J-Tea, a breathtakingly sumptuous imported-tea store added to the front of an existing house. In December, his Milwaukie Way will offer a fresh new take on “infill,” rising in an abstract black “ribbon” of offices and retail behind a 1929 Spanish Colonial building in Westmoreland.

Last year, with 10 projects in their final phase, Waechter created three types of models for each: In stark, white-painted wood, he lifted the building’s innards above its envelope to better reveal the relationship between the two. In elegantly bent plywood (or just simple blocks of wood and pegs), he built highly abstracted concept studies to consider the building’s most basic idea. And out of clumps of wet concrete (pictured), he revealed the rawest relationship between volume and massing.

“Design is a reductive action: You take away and take away until you can’t take away any further because the building doesn’t work anymore,” Waechter says. “With models, you can see which designs have done a better job.”

“They are a ‘working model’ in a greater sense,” he adds, “influencing and informing the next project.”