Portland Desperately Needs Affordable Housing. These 5 Cities Show a Way Forward.

Yes, Portland’s housing crisis is very real. Last winter, the city council unanimously approved “inclusionary zoning,” requiring 15 to 20 percent of new housing to go to people making less than 80 percent of the median household income. In the long term, this could mean the overall share of affordable units will grow. In that context, know this: affordable housing doesn’t have to mean boxy, bland apartment buildings—really.

Portland architects pondering this new wrinkle in the city’s pell-mell development boom—and developers looking to improve the city they’re rebuilding—should draw inspiration from their colleagues around the world. Here are five standout designs and strategies that take on the global conundrum of affordable urban housing with verve.

Go "Green Skin"

The Ginkgo Project in Beekbergen, Netherlands, an affordable housing project for residents living with mobility issues (pictured above), has a striking feature: a semitransparent exterior on one side that mimics the leaves of a ginkgo biloba tree, with shifting shadows, reflections, yellows, and greens that react to the changing light. The material choice is functional, blending the building into the park it faces and providing the long balconies with privacy. On the other side of the building, Dutch architecture firm Casanova & Hernandez used a more traditional brown brick to blend the structure into its residential neighborhood. “Beekbergen, as many other small towns of the Netherlands, is composed mainly by large single-family houses that are not affordable for young people and not suitable for older people with mobility problems,” the firm states. “The site is an interesting space located in between two zones with very different characters: the green area of the park on one side and the urban area of a postwar neighborhood built in the ’50s on the other side.”

A once-garbage-strewn Detroit field now has nine Quonset huts.

Image: Courtesy True North

Get Military

Prince Concepts constructed these nine Quonset huts on a once-garbage-strewn Detroit field, in a project newly dubbed True North. The New York–based firm took the simple, aluminum outsides—designed to cheaply house troops and equipment during World War II—and added modern flourishes—like wood and concrete accent walls, second floors, and gourmet kitchens. The new structures, which include a gallery and art studio, are intended to house artists in need of both living and working spaces, so Prince left the insides as a blank canvas. “The residences were delivered mostly raw,” the company says, “to provide the creative inhabitants an opportunity to design the way they’d like their laboratory to function and feel.”

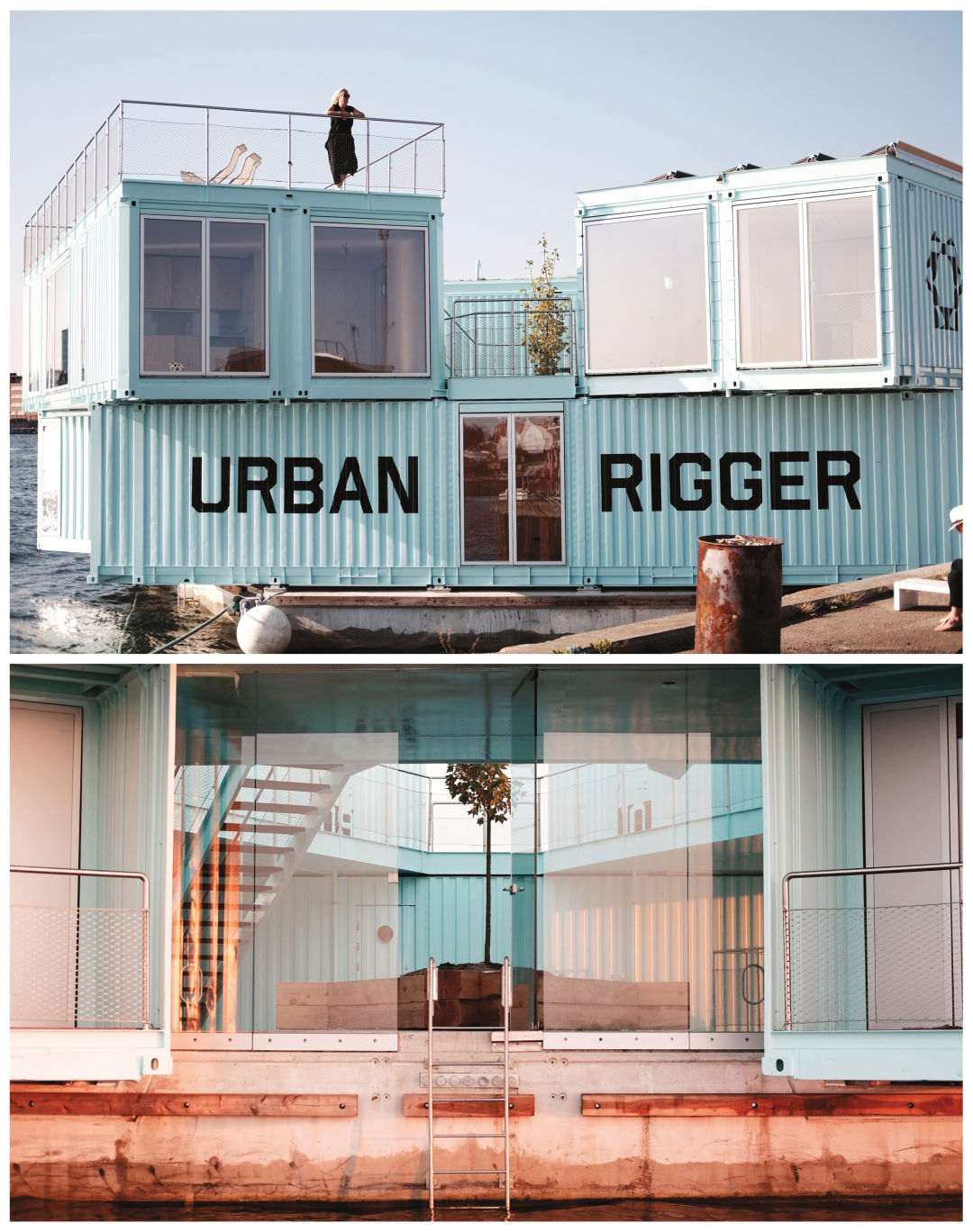

Architecture firm Bjarke Ingels designed 12 studio apartments for university students in Copenhagen.

Image: Courtesy Laurent de Carniere

Leverage the Water

Across Denmark, student applications are mushrooming—and with them the demand for affordable student housing near city centers. Architecture firm Bjarke Ingels artfully stacked nine used, cheap shipping containers on a floating platform in the Copenhagen harbor to create 12 studio apartments for university students. Called “Urban Rigger,” the structure has a shared enclosed courtyard in the center, and a grand rooftop area to foster a sense of community. “There are few strategies that allow cities to expand,” the firm says of the project. “Yet Copenhagen’s harbor remains an underutilized and underdeveloped area at the heart of the city. The housing is also buoyant, like a boat, so that can be replicated in other harbor cities where affordable housing is needed, but space is limited.”

Leave It Undone

In 2010, Chilean firm Elemental built 70 affordable units in Monterrey, Mexico, for a rock-bottom cost of $20,000 per unit. The twist: to stay within the budget, the firm left a modular, protected hole next to each unit for residents to expand into according to their means and needs. The entire structure is built around a central, communal greenspace (a luxury in this part of the country), and the blank, unconstructed areas reaffirm a sense of ownership that many such projects lack. From Elemental: “It was pertinent to use the strategy of investing state resources to build ‘the difficult half’ of the home, especially given the capacity do-it-yourself building observed in Mexico, ensuring a promising future for the expansions.”

Toronto's 60 Richman East aims to be a sustainable closed loop.

Image: Courtesy Scott Norsworthy

Hand Over the Deed

Ground-floor retail is already a common feature of Portland’s newest buildings. But this striking 11-story, 85-unit building in Toronto takes that concept and adds a new twist. Residents—primarily hospitality and restaurant workers priced out of homes in other parts of the city—run and own the ground-floor eatery. Indeed, 60 Richman East, from Teeple Architects, aims to be a sustainable closed loop. The resident-owned and -operated restaurant and training kitchen is supplied by communal gardens on the sixth-floor terrace (irrigated by stormwater from the roofs), and compost from the restaurant goes back up to the garden. “A housing co-op for hospitality workers that would be economical to build and maintain was a key inspiration,” according to Teeple. “The result is a small-scale, but nevertheless full-cycle, ecosystem.”