5 Amazing Portland Treehouses

The Star Hooch (above)

Built to withstand a hurricane, the 35-foot-high “Star Hooch” looks a little like an angular hot-air balloon lashed together by the Swiss Family Robinson. Designer Joe Scheer says it’s a Pacific Northwest hybrid of the vacation rentals he originally built in Rincón, Puerto Rico, as part of a project to convert 17 acres of agriculturally abused land back to tropical jungle. The small footprint minimizes site disruption and reduces structural interference with the earth.

Starting in fall 2012, Scheer and Troy Susan—owner of Bamboo Craftsman, an outdoor furnishings and garden store in North Portland’s Kenton neighborhood—built the Star Hooch with five locally sourced noble fir logs for support, creating a deck shaped like a pentagon. “Hooch,” Vietnam War–era slang for a thatched hut or improvised living space, was derived from “uchi,” a Japanese word for home.

The foundation is only about two feet deep, reinforced by rebar. Keeping the structure—essentially the skeleton of an upside-down tipi—upright and balanced are five cables connected to large trees, Bamboo Craftsman’s shop, and an old utility pole. When wind shakes the trees, the hooch moves, too. (It also shimmies when there’s a dance party on the top deck.) A corrugated metal roof keeps visitors dry, and a skylight in the middle lets in light. For a same-size star hooch in your own backyard, Susan and his team charge $30,000 to $35,000. Smaller versions start around $8,000.

Lindley Morton’s grandsons and friend lift sandwiches, Nerf guns, and other supplies with basket and pulley.

Image: Michael Novak

The Sky-High Fort

As boys, Lindley Morton and his brother’s tree house was their world away from grown-ups, their own private fortress where they could share meals, tell stories, and sleep next to the stars. Decades later, in May 2018, Morton decided to give his four grandsons a similar experience.

With his eldest grandson (also named Lindley), he sketched plan after plan as imaginations went wild. The result shares a key feature with the tree house of Morton’s boyhood—it is thrillingly, parent-terrifyingly high. Accessible by a steep ladder, the floor of Morton’s grandsons’ tree house begins at least 12 feet from the ground.

Constructing it was no mean feat. Morton and a friend built the roof and main structure on the ground and then used a hoist to get them into the towering cottonwoods. It was “deceptively cheap” to build, he says—approximately $500. Except for the clear plastic roof and some hardware, all the materials were recycled from Morton’s preretirement construction days or salvaged from the neighboring Columbia River beach.

The kids constantly have new ideas on how to improve the tree house. The next project? Build a lower level set into the supporting braces with a zip line to the beach.

Morton hopes the additions will keep the grandsons interested for years. “It won’t be finished, ever. It’s one of these things that grows.”

Image: Michael Novak

The Lofty Guesthouse

When Scott and Lisa Brock and their two sons need a break from Portland’s city life, they fly their single-engine Piper Comanche 25 minutes to their log cabin and guest tree house in Goldendale, Washington. As you do.

Begun shortly after their wedding in 2015 and completed last spring, the tree house rises 34 feet off the ground, from their twin sons’ initials carved into the cement support of the two-landing staircase to the peak of the metal roof.

The tree going through the deck is the main support. (It’s outside the house, to avoid inviting insects inside.) Cedar shake siding keeps things woodsy and fragrant. Using ponderosa pine from the property (the trees had been killed by pine beetles) saved approximately $10,000 on beams, walls, cabinets, sink top, bed, and other furniture. Out of pocket, the Brocks estimate they spent $25,000 on materials. (The labor was courtesy of Scott and some friends.)

The cost is offset by year-round enjoyment—cross-country skiing and snowshoeing in winter (when they’re more likely to drive there than fly), listening to the rain drum against the roof during the wet seasons, and making dinner in the outdoor pizza oven on summer evenings. They’ve started listing the tree house (which sleeps three comfortably, or four if two of them are preschoolers) on Airbnb. Alas, renters don’t also get the quick flight.

Image: Michael Novak

The Disney House

In 2001, when his first daughter was born, Mississippi Pizza Pub owner Philip Stanton decided to build her a backyard tree house beneath a shady black walnut. He planned to spend no more than $500. Since then he says he’s spent more like $5,000 or $6,000—he never dared to add up the dollars—on ReBuilding Center treasures for their arboreal abode. After swapping a cumbersome ladder for a metal spiral staircase about a year into the project, Stanton says, “It started to feel like it was a little magical.”

His late brother, Tom Stanton, the same artist who made the Mississippi Pizza Pub’s ornate stained glass artworks (including a stunning mermaid by the back bar), added to the alchemy by creating and installing a whimsical stained glass portrait of time and space, depicting the phases of the moon and sun through the seasons. (Disney recognized the magic last summer and shot a scene at the tree house for the upcoming film Timmy Failure.)

Summer evenings, the Stantons and their friends gather in the tree house for adult sing-alongs, with violins, guitars, mandolins, and the occasional flute. As his children outgrow the tree house (the youngest is now 10), Stanton plans to devote more space to art and music by improving the walls’ acoustics and adding Victorian decorative pieces outside, to match the main house. “The tree house will never be fully finished,” says Stanton. “I already have new ideas for it.”

Image: Michael Novak

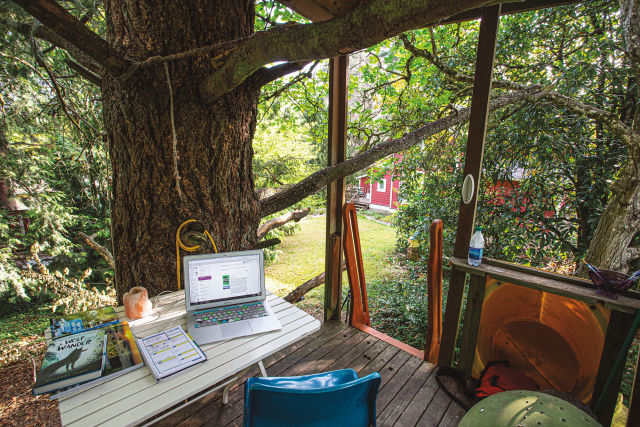

The Novelist's Nook

Local children’s novelist Rosanne Parry describes her tree house as “more a glorified climbing structure.”

In 2003, she purchased an 1890 gothic dairy farmhouse. A platform in some backyard branches inspired a tree house summer office where she could write and watch her four children play.

Eyestrain prevention—by peering out to the vista, especially nearing a deadline that requires long hours of diligent focus—is one perk of an outdoor office.

Image: Michael Novak

Using many recycled materials and hand-me-downs, Parry added a basic roof and picket railing. Roll-up blinds block sun and rain from her computer screen, while the inside is furnished with Ikea office pickings. Through the years, the children added a rock-climbing wall and a zip line to a neighboring tree as not-at-all-self-motivated Mother’s Day presents. After her foot surgery, Parry’s husband replaced the pirate ladder with a homemade ship ladder that was easier for both her and her then-octagenarian father to climb. In the 16 years of its existence, Parry estimates they’ve spent less than $500 on her orchard office.

“I write for a living, so there’s no way I can afford one of those fancy-dancy tree houses,” says Parry. “And if we did something more enclosed, animals would come in here and poop. We decided to make it as much like the tree as possible so that we seldom have to deal with the more unpleasant bits of nature.”