A New Portland Group Fights Gentrification by Renovating Black-Owned Homes

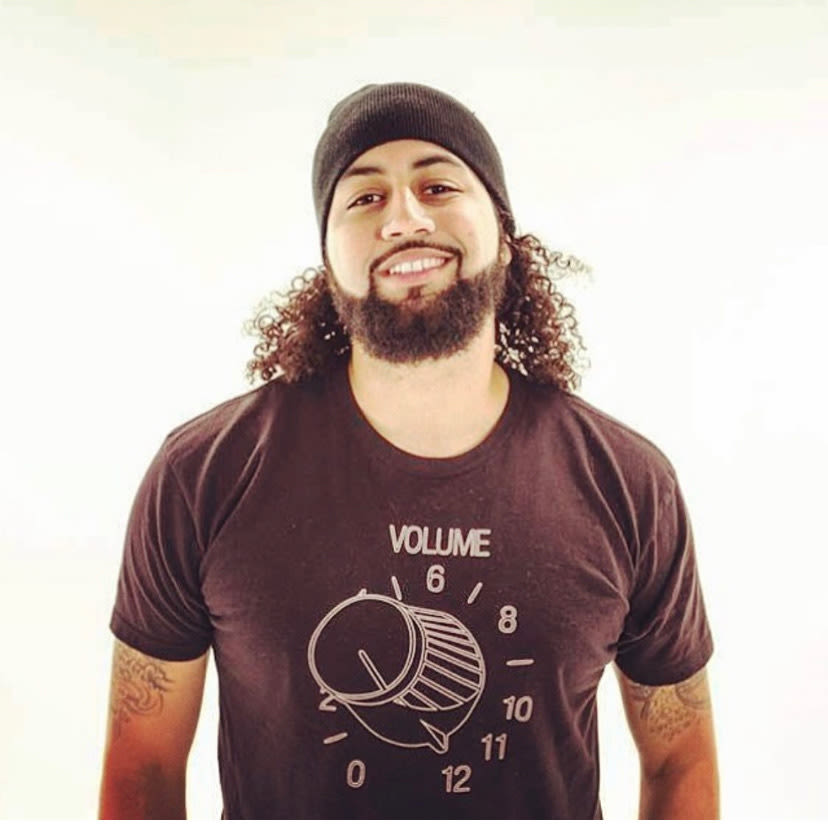

Activist and musician Randal Wyatt founded Taking Ownership PDX to support Black homeowners and fight against gentrification.

Image: Courtesy Adrian Adel

Activism is no trend for Randal Wyatt.

The 35-year-old hip-hop artist born and raised in Portland has been a fixture in the local Black community since long before George Floyd’s murder ignited two months of protests and brought federal officers to town. Since May, Wyatt, a member of the band Speaker Minds and a longtime mentor of BIPOC youth, has been inundated with messages from fellow Portlanders.

He says people were reaching out “trying to get information about how they can be allies.”

His answer? Support Black homeownership.

“My idea was to go out and repair and revive Black-owned homes and businesses,” Wyatt says, “to raise property values in these very small and dwindling communities that Portland has, because of displacement, gentrification, and redlining.”

Within a couple of weeks of airing his plan online, Wyatt says he received almost $10,000 in donations, as well as messages from a bevy of real estate agents and contractors.

Working on a home for the Taking Ownership program

Image: Courtesy Randal Wyatt

In June, Wyatt channeled that support by launching Taking Ownership PDX—a coalition of real estate agents, contractors, and others whose aim is to renovate and revive Black-owned homes in order to fight gentrification while enabling Black Portlanders to age in place and generate generational wealth.

Last month, Wyatt quit his day job to focus on Taking Ownership full time. He is working to register the organization as a formal nonprofit. Until then, Friends of Noise, a Black-owned Portland nonprofit, is the group’s fiscal sponsor—which means that when people donate, they can still get a tax write-off. Taking Ownership has already started three renovation projects—hiring only Black and POC-owned services to do repair work—and has requests for many more. By September, the group hopes to raise $100,000.

Help from Taking Ownership means one 50-year-old Lents resident, the first to take part in the Taking Ownership program, will be able to continue to afford mortgage payments on her Lents duplex.

The homeowner, a Portland native who requested to remain anonymous, worked in dentistry for more than 20 years before a multiple sclerosis diagnosis forced her to cut her hours and eventually stop working. To afford her mortgage payments, she rents out half of her duplex. Before contacting Taking Ownership, the rental required some crucial renovations.

“I'm pretty much disabled and I hadn’t been working prior to this pandemic,” she says. “It put the icing on the cake.”

Wyatt helped to replace the duplex unit’s carpets and front door, installed a new refrigerator, and took out moldy windows.

“Not everybody can pay for everything all the time,” the homeowner says, “and in this environment, we just don’t know what tomorrow might bring.”

That real estate agents—who inherently benefit from the gentrification of Black communities—are getting behind Taking Ownership might seem surprising. But some see it as a means of repairing entrenched inequities by taking action.

Lauren Goché, one of the Portland agents who sits on Taking Ownership’s 11-person board of directors, says the current real estate market has “exploded,” which has only widened and exposed the city’s economic and racial divides.

“It's been a sellers’ market for the last seven years,” Goché says, with “low inventory and high demand, which drives up prices. June numbers came out, and the inventory is the lowest it’s been in years.”

Portland’s cutthroat housing market particularly impacts Black homeowners, who are subject to predatory development practices and who have been exploited over a century of displacement and disinvestment via legacy racist housing covenants.

Tom Armstrong, a supervising planner with Portland’s Bureau of Planning and Sustainability and one of the coauthors of the city’s Historical Context of Racist Planning report, says exclusionary housing practices began in the early 20th century. Covenants written into property deeds prohibited who could live on or own a property based on race. At the same time, redlining practices—which deemed certain areas “risky” and precluded lenders and real estate agents from approving loans or mortgages—annexed communities of color in certain neighborhoods.

“There were very few places in town where African Americans could purchase a home or rent a home,” Armstrong says. “Those were predominantly focused in the Albina community in Northeast Portland.”

Though the practice of redlining was banned in 1986, disinvestment and gentrification have continued. In the ’50s and ’60s, construction of Interstate 5 and Memorial Coliseum, as well as the expansion of Emanuel Hospital, carved up the Albina neighborhood and pushed out Black Portlanders. Between 1990 and 2017, Armstrong says, “over 4,000 households and more than 10,000 African Americans have been displaced from the Albina neighborhood.”

For Goché and other real estate agents, Taking Ownership represents an opportunity to combat that inherent racism. Portland’s Urban Nest Realty just announced a $10,000 donation match for the group.

Should the organization continue to grow, Wyatt hopes to fund down payments beyond 20 percent on homes for Black families. He’d also like to be able to provide job training for formerly incarcerated people of color.

“Taking Ownership is an avenue of reparations,” Wyatt says, “and that’s what the Black community is going to need.”