How Retired MAX Cars Could Help Portland’s Most Underserved Communities

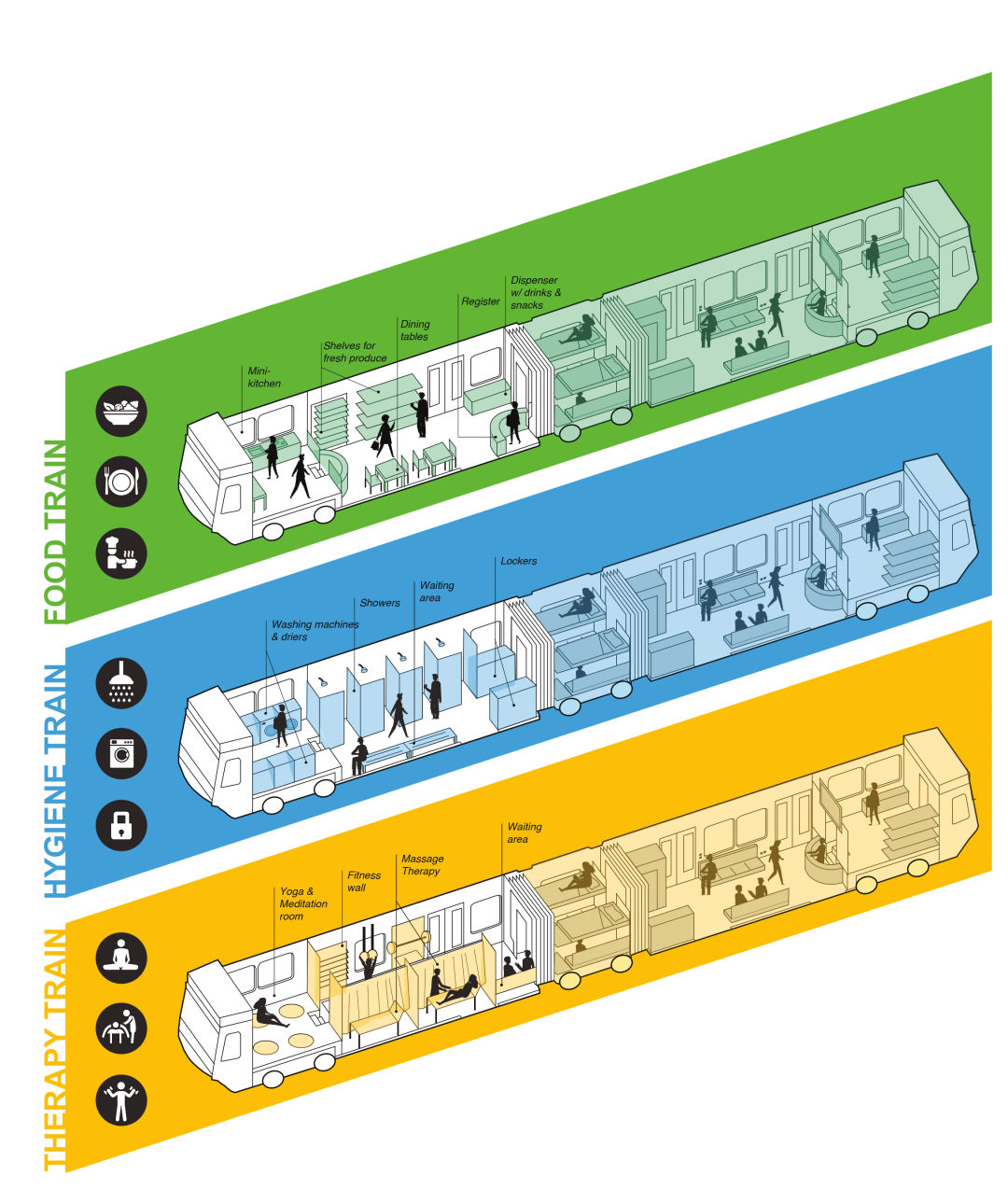

The Afro Village Movement rendering

When the first MAX cars were rolled out in ’86, it revolutionized other midsize cities’ notions of what public transit could be: something in between limited-capacity trollies and the massive subway systems of New York or Chicago. It was the perfect solution for big small towns like ours.

Fast-forward to now: TriMet is preparing to roll out its most modern MAX cars to date, the Type 6 models. They’ll be leaps and bounds beyond the originals—featuring high-def dynamic route maps and stop displays, improved security features, and easy ADA access. When they’re introduced, between 2021 and 2022, they’ll replace 26 of the oldest, Type 1 MAX car models. Rather than watch these iconic artifacts of Portland history thrown into a landfill, Portland State University’s Center for Public Interest Design and the city’s Bureau of Planning and Sustainability saw an opportunity to give back to the area’s most underserved communities.

Hoping to open up the conversation, CPID and BPS partnered up and launched the MAX Reuse Design Challenge. Ten local designers submitted plans for how they’d transform the decommissioned cars. While the prompt itself was open-ended, all of the entries sought to address issues of inequality. The results ranged from a commercial pop-up space for aspiring businesswomen and nonbinary folks to storage space and laundry facilities for people experiencing homelessness to a kitchen, learning center, warming shelter, and health clinic, all posted up along Holladay Park.

Visitors at an exhibit in the Oregon Rail Heritage Center voted on a People’s Choice winner, and it was a landslide for “The Afro-Village Movement,” a collaborative effort between Marta Petteni, an Italian architect at PSU’s Homelessness Research and Action Collaborative, and Laquida Landford, a longtime housing and racial justice advocate. It stood out from other contestants in a major way: its three trains (offering food, hygiene, and therapy, respectively) would remain mobile. This feature was inspired by the work of Landford herself.

“Laquida has always been going where the need is,” explains Petteni. “These trains are actually doing what Laquida is doing: moving throughout the city, reaching communities, and bringing services there.”

“You can see the history connecting history,” adds Landford. “This movement isn’t about me. It’s about our history and how we fit into this city.”

It’s a long road ahead to making any of these designs a reality. Even with the MAX cars coming for free, construction will be expensive. It will take investment-ready community partners, the go-ahead from TriMet, and more. But Todd Ferry, senior research associate at CPID, is hopeful.

“They did something truly revolutionary with these MAX cars,” he says. “I think we need that same revolutionary spirit now.”