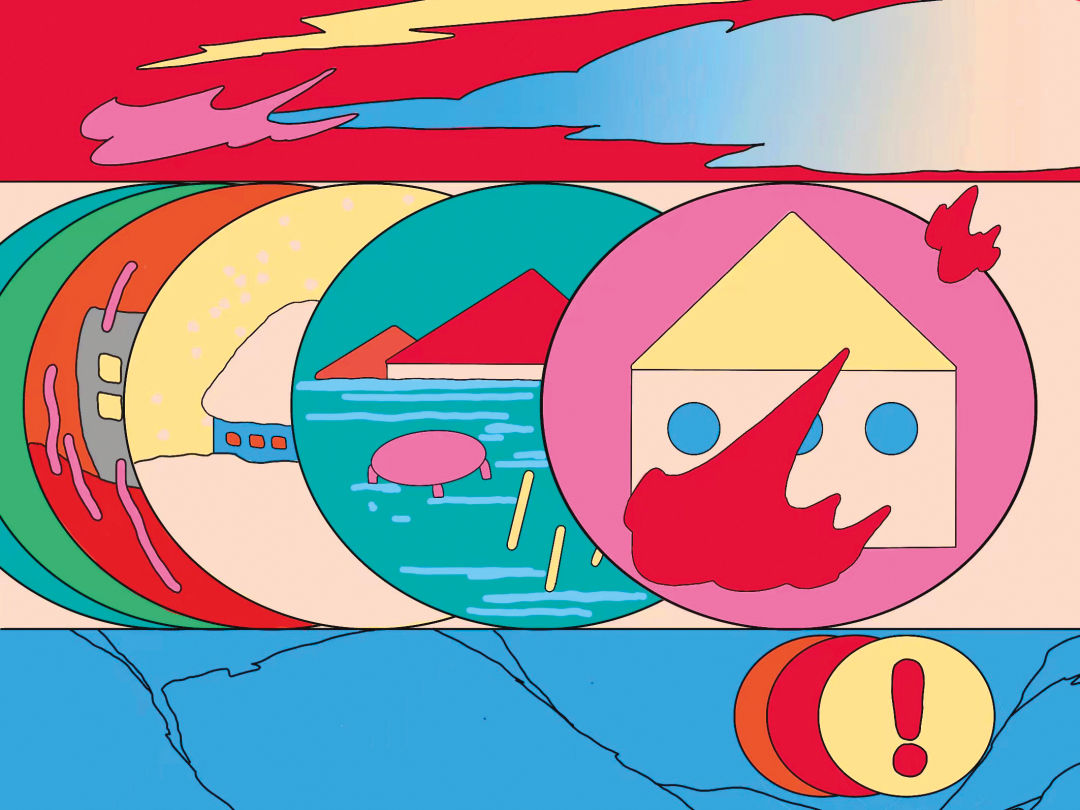

How to Prepare a Portland Home for Earthquakes and Wildfire Smoke

Image: SanQian

Natural disasters, like floods, landslides, tsunamis, earthquakes, and wildfires, come with the territory in Oregon—though an argument could be made that there’s nothing natural about the scale or pace of disasters we’ve seen in recent years. Wildfires are becoming more frequent and catastrophic around the globe, and the western United States is no stranger to their devastation. More than one million acres of land burned in our own state in 2020, destroying over 4,000 homes. With a rapidly warming planet, fire seasons in Oregon are expected to become longer and more severe. For the Portland community, this means preparing for a new normal: bad air days.

Another major hazard—the Cascadia megaquake—may not even be on your radar, but it should be. Off the Pacific coast is the Cascadia subduction zone, where the Juan de Fuca tectonic plate dives beneath the North American plate, slowly building pressure before it ruptures, potentially producing a magnitude-9 earthquake, with an estimated five to seven minutes of shaking. When the next earthquake will happen is impossible to predict, but it could strike at any time, with profound damage.

Here are steps you can take to protect that big investment, your home (not to mention yourself inside it), from two looming hazards of living in Oregon.

Living in the Fault Zone

We Portlanders inhabit a very seismically active region. The last major quake in the Cascadia Subduction Zone occurred more than three centuries ago, but there’s a 37 percent chance Oregon could experience a 7.1-plus magnitude quake in the next 50 years.

The Big One spells big trouble for Portland, a city that is greatly underprepared for a major earthquake. Most of its bridges would collapse or suffer extensive damage. Portland has more than 1,600 unreinforced masonry buildings, which are more vulnerable to severe structural damage or collapse. And as for homes, well, the good news is wood-frame houses tend to perform well in earthquakes, but a house that is not adequately anchored to its foundation can slide off of it during an earthquake. “It usually doesn’t collapse down and crush people, but it can be distorted to the point where you just have to demolish the house,” says Yumei Wang, a geotechnical engineer and earthquake expert. “This is more important if you’re on a hill or if you’re near a body of water like a river or lake, because the sediments are usually more susceptible to liquefaction and lateral spreading.”

The average seismic retrofit, such as bolting your mudsill and cripple wall bracing, can cost between $4,000 and $10,000.

It wasn’t until 2003, when the state adopted the 2000 International Residential Code, that mandated new homes be designed with enhanced bracing criteria to better withstand earthquakes. Wang knew her Portland home, which was built in 1995, had “inadequate anchorage,” she says. “When I did it, I hired a contractor and I told him where I wanted the bolts.” One to two-story, single-family homes on flat ground typically do not require an engineer or architect for seismic strengthening, but you may want to hire a contractor who specializes in seismic retrofits.

The city of Portland offers a seismic strengthening brochure on its website, outlining cost-effective methods for protecting your home from severe damage in an earthquake. Common problems include older homes not being bolted to their foundations or weak bracing materials on the cripple walls (the short wall between the foundation and first floor of the house). The average seismic retrofit, such as bolting your mudsill and cripple wall bracing, can cost between $4,000 and $10,000.

If you can afford the cost of labor and materials, or perhaps you’re handy enough to make it a DIY project, you may want to invest in retrofitting your house. But there are lifesaving steps you can take to make your house safer in an earthquake. Wang suggests that homeowners and renters secure tall furniture, use Velcro fasteners for computers and other electronics, and apply museum putty to keep artwork and decorative objects in place.

“It’s also very important to make sure that your water heater is braced and strapped so that it doesn’t fall over. And it’s also important to know how to turn off your natural gas at the meter,” Wang adds. She recommends installing excess-flow valves or seismic shutoff valves, which can halt gas flow in the event of an earthquake.

Preparing for the Big One may be in the back of your mind most of the time. How many of us go about our day-to-day lives thinking about the possibility of an earthquake? But when an earthquake hits, it’s critical that you are ready for it.

Wang says you should be self-sufficient for a minimum of two weeks. Pack an emergency kit of nonperishable food, water, water purification tablets, and medicine. And have an earthquake safety plan for yourself and loved ones. “How are you going to get your kids back [from school] if you work on the other side of the river? Is your workplace safe?” says Wang. “And if you lose electricity for an hour, it’s not the end of the world—but imagine losing electricity for a couple of weeks. You can actually live without electricity, but just preparing for that is a good thing psychologically.”

Keeping Wildfire Smoke Out

As wildfires raged across Oregon in 2020, Portland became almost otherworldly; smoke lingered in the air and the city’s skyline turned a fiery red and orange for days. The air quality reached such dangerous levels that the international air quality monitoring platform IQAir.com ranked Portland as the city with the worst air on the planet.

Extreme wildfire events are becoming more prevalent in the western United States, and the resulting smoke—a mix of particulate matter and gases—can have serious health effects, especially for at-risk populations, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. When outdoor air quality becomes hazardous, public health officials urge folks to stay indoors and shut doors and windows to reduce exposure. But outdoor air can still sneak into your home through mechanical ventilation—bathroom fans, range hoods, and HVAC systems with a fresh air intake—or through cracks and gaps in the building envelope.

“Indoor air is usually more polluted than outdoor air, which is, I think, a fact that is surprising to most people."

“In most circumstances, from an air quality perspective, bringing in outdoor air is actually a good thing,” says Dr. Elliott Gall, an associate professor of mechanical and materials engineering at Portland State University whose technical specialties include human exposure to air pollution. “Indoor air is usually more polluted than outdoor air, which is, I think, a fact that is surprising to most people. We don’t view our homes that way.”

During wildfire season, though, “ventilation starts to work against us from the context of indoor air quality,” Gall says. He suggests minimizing use of bathroom or kitchen fans that vent to the outdoors. For homes with central heating and cooling systems or window air conditioners, you can turn it off, set to recirculate mode, or close the fresh air intake, the EPA recommends. Upgrading your HVAC’s air filter to one with a higher minimum efficiency reporting value (MERV) rating is more effective for removing smoke from your home. By closing windows and doors and using an air filtration system, you can cut the amount of particulate matter in your home or apartment by half, according to a study from the University of California, Berkeley.

“There are commercial air cleaners that can do quite a good job at removing particles from air and providing a large flow rate of clean air,” Gall says. Commercial air cleaners that come with HEPA filters and activated carbon filters remove both the particles and gasses in smoke, but they can be pricey. DIY options like the Corsi-Rosenthal Box—made out of MERV-13 furnace filters taped against a box fan to form a cube—are simple to build, largely effective, and put less of a strain on your wallet if you cannot afford a commercial air cleaner.

Where you put the air cleaner matters. The EPA recommends designating a clean room during air quality events. You should pick a room that can fit everyone in your household, such as a bedroom, and temporarily close points of outdoor air entry. If you buy an air cleaner, Gall recommends selecting one with a clean air delivery rate (CADR) of at least two-thirds the floor area of the room. “[A clean room] is going to go a really long way, I think, in maintaining your health and sanity during a wildfire event,” he says.

The work’s not done when the smoke clears, however. Part of Gall’s research into indoor exposure includes the lingering effect of wildfire smoke on home surfaces. “We chose to look at a specific class of compounds called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which are compounds that are generally formed as a result of combustion,” he says. “They’re elevated in wildfire smoke, and they’re also of concern because, generally speaking, they are highly toxic.”

PAHs can stick to surfaces like glass and cotton, and can persist for weeks. But Gall and a team of student researchers have found that putting a cotton bedsheet in the laundry, followed by a tumble dry, removed between 60 to 80 percent of accumulated PAHs from the sheet, reducing skin contact with known carcinogens while sleeping in your bed.

“If you have a long-lasting smoke event like we did in 2020, do a load of laundry of your bedsheets and clothes that you wear frequently,” Gall says. Using cleaning products on nonporous surfaces like glass also helps remove PAHs, he adds.

Air quality can be easy to ignore if it’s not immediately visible to the naked eye, but there are benefits to tending to indoor air quality, even if when there’s not a wildfire. “During a wildfire event, people start to pay attention and sort of get things up and running, Gall says. “So, it’s a good time to get people thinking about air quality and hopefully building good habits.”