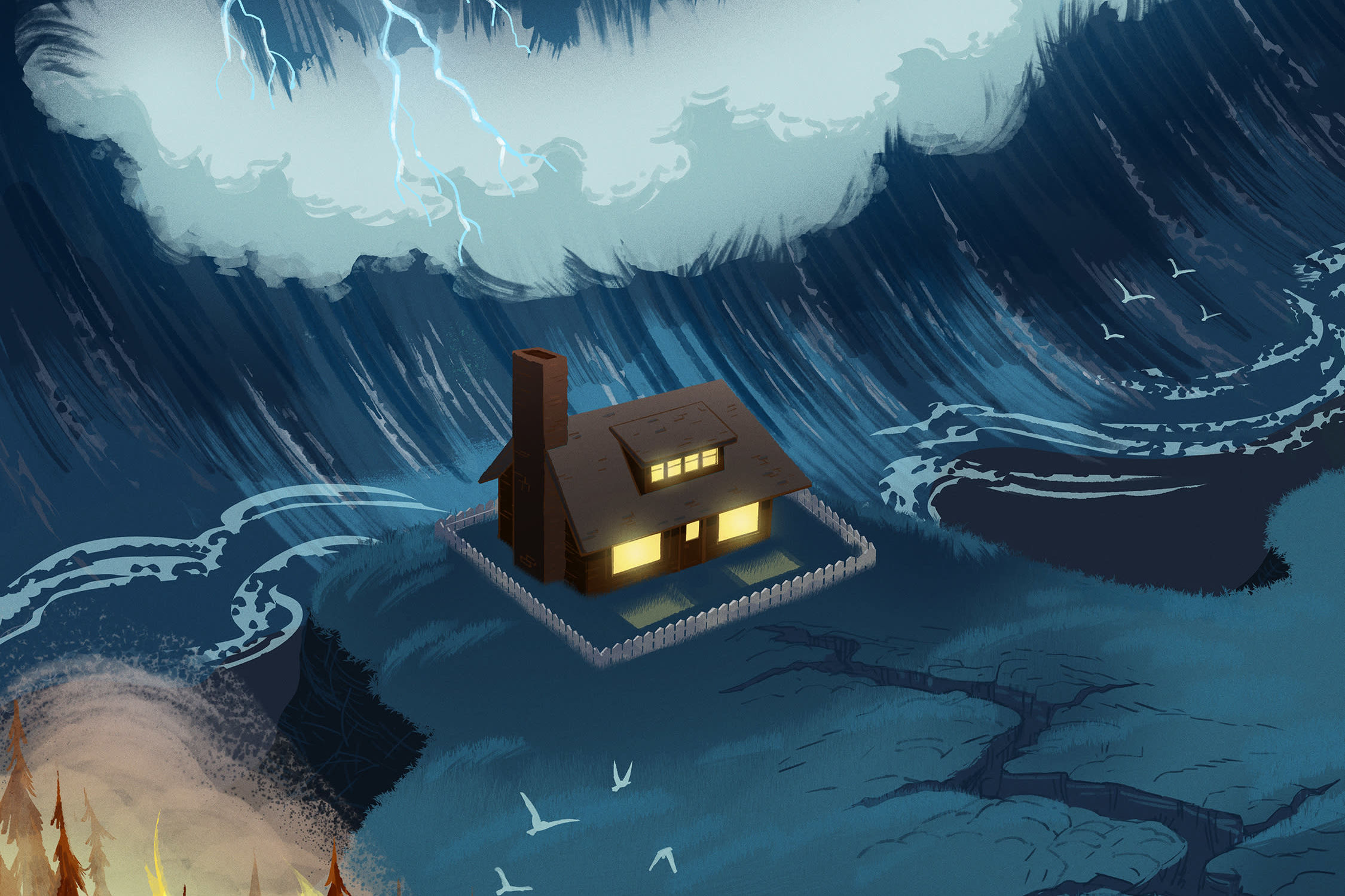

The Big One Is Coming. What Will Happen to Portland?

Think of Oregon geology as a clock, measuring time in earthquakes—46 major coastal quakes over the last 10,200 years. Tick: a magnitude 8 on the Richter scale. (Bigger than the quake that killed 63 people in the Bay Area in 1989.) Tock: a magnitude 9. (Same as the 2011 quake that killed almost 16,000 in Japan.) On average, a major quake uncorks in this area every 243 years, the last one on January 26, 1700—318 years ago.

Right. We’re overdue.

When the next Big One does happen, a 700-mile chunk of tectonic plate known as the Juan de Fuca, stretching from British Columbia to Northern California, will slide beneath the North American plate, causing the entire Northwest coastline to sink by up to 6.6 feet. The resulting quake won’t be a California-style short blast of energy along a fault line in the earth’s upper crustal zone. It will be bigger, deeper, and longer: 5–7 minutes, with potentially dozens of aftershocks, some very powerful, for days, even months, later.

Hillsides will slide. Buildings will collapse. Roads will buckle. High-rises will sway. Bridges will crack. Some will fall. Pipes will snap. Within 20 minutes, the first of several 30-100-foot tsunami waves will wash the Oregon Coast’s low-lying towns away.

If our next “subduction zone” quake unleashes its full potential, it will be the worst natural disaster in US history. But there are crucial steps we can take, as individuals, families, and a community. Preparation may mean the difference between finding your loved ones or not; between sleeping inside your mildly damaged house or on a cot in a refugee center; between going hungry and thirsty for days or managing until supplies arrive. And, yes: between living and dying. For the Northwest, preparedness could mean the difference between bouncing back in years or not bouncing back for decades.

Officials are working hard on the problem. In 2013, more than 160 scientists, engineers, and infrastructure managers volunteered thousands of hours of time to develop the Oregon Resilience Plan, a blueprint for averting the worst scenarios and a quicker recovery. “[B]usiness as usual,” the panel concluded, “implies a post-earthquake future that could consist of decades of economic and population decline—in effect, a ‘lost generation’ that will devastate our state and ripple beyond Oregon to affect the regional and national economy.”

With their recommendations in mind, here’s a guide to what’s being done and what all of us should do. The Big One is inevitable—right now, or 50 years from now. What happens before and after is up to us.

What buildings will fall down?

We like old buildings and have a perennially weak economy. Result: Portland has about 1,650 “unreinforced masonry” (i.e., old brick) buildings, more than 40 of them schools or day cares. If not retrofitted, they are all likely to collapse. More modern steel and concrete buildings will stand, but that doesn’t mean they’ll be safe to enter or use postquake. One of the best seismic building systems is called “base isolation,” in which buildings slide atop pads within a kind of tub. Japan had 2,600 base-isolated buildings before the 2011 quake. Portland has one: Pioneer Courthouse, retrofitted in 2005.

What we’ve done In 2012, Portland voters passed a $482 million bond to improve schools, much of it planned for seismic retrofitting. In 2016, the annually funded Seismic Rehabilitation Grant Program provided a record-breaking $125 million to schools and $30 million to emergency service facilities for structural seismic improvements. And back in 1998, a bond allowed the Portland Fire Bureau to retrofit or rebuild all 30 of its facilities for the strongest earthquakes. The bureau also now has “urban search and rescue” squads on both sides of the river trained to find people in rubble. “One of the biggest challenges in disaster planning is making a plan based on what people will do, not what you want them to do,” says Alice Busch, Division Chief of Operations for Multnomah County’s Emergency Department.

What we should do A Policy Committee was assembled by Portland City Hall in 2014, bringing together the Portland Bureau of Emergency Management, Prosper Portland (then the Portland Development Commission), and the Bureau of Developmental Services to work with community stakeholders to scrutinize the state of city’s crumbling, unreinforced sprawl. A few of their recommendations after three years of study and debate: A property tax exemption to help offset the costs of retrofitting, as made possible by 2017’s Senate Bill 311; increased state funding for high-priority school retrofits; and a less rigorous program of seismic upgrades for public buildings like churches, which are tax-exempt.

What about my house?

Wood-frame houses generally fare well in earthquakes. But of Portland’s estimated 152,800 single-family homes, 78 percent were built before the first seismic code in 1974. That means they probably are not bolted to their foundations—and will thus rattle off and be largely uninhabitable.

What we’ve done With $100,000 in FEMA funds, former city council member Steve Novick started a pilot program for 22 homeowners to bolt their houses down. He also did his own. Cost: $4,000. So did Carmen Merlo, former director of the city’s emergency bureau, whose complicated foundation necessitated lifting her house. Cost: $25,000. With a second $500,000 FEMA pre-disaster mitigation grant, 116 homes had been completed as of December 2017.

What we should do Just do it. Anchoring most homes costs no more than $5,000. For those in the market, buyer beware: House Bill 2140, passed in May of 2017, requires property owners to disclose seismic risk to prospective buyers.

The Family Plan

When the big shake comes, you’re going to want to connect with your brood as quickly as possible.

Sit down with your family and/or friends to discuss what to do. Imagine different times of day and scenarios—particularly who will be on what side of the river.

Set up at least two places to meet: one outside of your home, the other outside of your neighborhood.

Designate a contact—outside of Portland. Phone lines within and into the city will be jammed. Outbound calls, however, should be easier to make, particularly to other regions of the country. Aunt Myrtle in Kansas, or your college roommate who lives in Manhattan, can become a central information hub.

Know your evacuation routes! Portland’s emergency planners have developed hazard maps for every neighborhood that include evacuation routes, hospital locations, and other emergency services.

Have family documents organized and ready to grab and go. That means Social Security cards, insurance information, passports, and birth certificates.

Get some bikes. Fuel might be tight for days, even months. You’ll need to get around. And what’s more fun than family bike rides? We won’t have Netflix for a while.

How will we get around?

By foot, bike, and boat, mostly. The region’s quake planners agree: people will be stuck where they are for quite some time. Prepare to bond with the people you’re with—whoever they are—or get walking.

BRIDGES: Top-heavy, counterweighted lift spans like the Hawthorne, Steel, and Interstate will likely be impassable. So will ramps leading to just about all the bridges.

ROADS: Vast swaths of the city’s roadways, built on fill and alluvial deposits, will crack and sink.

THE TUNNEL: Highway 26’s West Hills Tunnel was built before seismic codes. ODOT is fairly confident that reinforced tunnels like Vista Ridge will stand strong in a Cascadia-type earthquake, but no official tests have been done.

THE GEAR: Most of the city’s road-clearing equipment is stored beneath the certain-to-collapse Fremont Bridge ramps and I-5. Seemed like a good idea at the time!

THE FUEL: Most of Oregon’s fuel supply arrives to the “Critical Energy Infrastructure Hub,” a six-mile stretch of fuel storage tanks and distribution terminals next to the Willamette River between the St. Johns and Fremont Bridges—all built atop vulnerable fill and alluvial deposits. Several multinational energy companies are involved; some have seismically upgraded some of these facilities, others have not. Most fuel gets here by way of a single, vintage 1960s pipe from Washington—owned and operated by BP—beneath the Columbia and Willamette Rivers. The movement of the rivers could cause the pipe to snap. In other words, peak oil (and natural gas) may come a little early.

STANDING SPANS: The Tilikum Crossing, Sellwood Bridge, and Sauvie Island Bridge are all built to withstand major earthquakes, as is the aerial tram. Multnomah County is working to replace the current Burnside Bridge with a seismically sound version; as of April 2024, construction is not set to begin until 2028.

THE BOATS: The Portland Spirit, tugs, and other rivercraft will become ferries.

What will we eat?

“Portland’s DIY mentality will help,” says Merlo. “The people who preserve their own food, ride bikes, catch rain water, raise chickens, and garden will thrive after an earthquake.”

Yes, it’s that bad. Consider:

- The quake will shake the whole Northwest, from British Columbia to California.

- Grocery and “big-box” stores built before the 1995 seismic-code upgrade are likely to suffer severe damage, according to Oregon planners.

- I-5 bridges, highways, and railroad lines may not be passable.

- Only one Port of Portland terminal (6) has been seismically retrofitted.

- Anyway, the post-quake tsunami is likely to devastate the jetties at the Columbia River’s mouth, making the famously tricky bar crossing even more treacherous. Pile dikes (which keep the channel deep enough for large shipping vessels to navigate) could collapse, making the lanes impassable.

- Portland International Airport sits on the kind of loose fill that turns to jelly—a phenomenon known as liquefaction—in an earthquake.

- If PDX is crippled, FEMA’s primary emergency response airport is in Redmond, 145 miles away.

What we’ve done Multnomah County has partnered with the Red Cross and other emergency organizations to create list of potential shelters with the unofficial promise that they’ll adopt anyone who comes to them in need. “We’re on the cutting edge,” says Alice Busch of the county’s emergency services department. “We’re encouraging people to be self-reliant.”

What we should do Retrofit critical routes. Create an inventory of World War II–style temporary bridges. Stock up.

Befriend a neighbor who makes kimchi. Could come in handy.

What will we drink?

Before Bull Run, booze was safer to drink than water. Turn the clock back. Your faucets (and toilets) will be dry for weeks, maybe months. The Bull Run dams are expected to survive, but 60 percent of the city’s water mains are brittle cast iron. Reservoirs will crack and pump stations will fail. The result: a total loss of water pressure—both for drinking and for putting out fires. For the first couple of weeks, water will have to be pumped, purified, and trucked. Firefighters will pump the Willamette into 10,000-gallon tank trucks, or directly to fires with Portland’s three fireboats. Sewers will fail. Bucket-flushing toilets at home will only clog the system. Going au naturel, over time, will pollute the ground supply and river. Figure on a year to flush.

What we’ve done The Portland Water Bureau has strengthened one conduit from Bull Run, with plans to update others in the future. New tanks were completed at Powell Butte and Kelly Butte in 2014 and 15, respectively, followed by Washington Park in 2025.

What we should do Upgrading the entire system would be like rebuilding the city. Planners recommend a “backbone” of new pipes to critical care facilities, firefighting nodes, and distribution points. The Water Bureau plans to complete a seismically “hardened” water line across the Willamette, though the project has been postponed until 2027 amid feasibility concerns and supply chain issues. At home, invest in a storage tank or water purifier. The Portland group Public Hygiene Lets Us Stay Human outlines an emergency “two bucket” toilet system to maintain hygiene.

How will we communicate?

Smoke signals! Kidding. Well, maybe.

Phoning within the city, checking Facebook, and doing business may be difficult for weeks. Vulnerabilities range from major fiber lines running underground and over those damned bridges to wireless antennas sitting on liquefaction soils or on buildings that will collapse or be unusable. According to the Oregon Resiliency Plan’s analysis, restoring full communications will take up to three months.

What we’ve done The city has established a network of 50 Basic Earthquake Emergency Communication Nodes that will be deployed in red tents in parks and open spaces throughout the city to receive shortwave radio transmissions.

What we should do Get to know your neighbors, so when the shaking stops you have the beginnings of a cohesive community. Figure out the planned site of the nearest emergency node—find maps here. Designate a family contact outside the western states.

And join the safety net!

Portland’s population: 640,000. Professional emergency responders: 2,100. Do the math.

“You shouldn’t expect the knight in shining armor to come in and rescue you,” says Marcel Rodriguez. “If you’re going to be rescued, it’s going to be by your neighbors.” Rodriguez, a 51-year-old mergers and acquisitions specialist, joined the Riverdale–Tryon Creek Neighborhood Emergency Team (NET) over a decade ago. Trained by the city-run program in basic first aid, fire suppression, rescue, and other handy skills, he and the 1,514 other local NET members covering 74 neighborhoods plan to offer cohesion amid chaos. Yet according to Merlo, we still need more—way more. San Francisco, she points out, has 29,000 trained volunteers.

Anyone 14 or older can join a NET by completing an online training course of 17 introductory videos and undergoing a mandatory background check. Then comes a seven-session course, culminating in a four-hour exercise in the field. There is also an intensive version, given in three, all-day Saturday sessions.

“We don’t need everyone to be a ‘doomsday prepper,’” says Rodriguez. “Just tackle the small scale: make sure your family is safe, then your neighbors, then your neighbors’ neighbors, and go from there. Having a basic plan and some basic skills gets you a foothold.”

And, er, this tsunami?

The Japanese earthquake in 2011 generated tsunami waves up to 33 feet high, washing over roughly 217 square miles. The Northwest’s wave could reach heights of up to 100 feet in the case of a 9.1 magnitude quake. The 33,000 full-time residents who live in the areas the tsunami will flood—plus tourists—will have just 15–20 minutes to get themselves to higher ground. Consider Seaside, where 86 percent of the population and almost 100 percent of the city’s critical facilities are in the tsunami zone. (The state geology department offers a trove of maps and other information.) For people in the inundation zone, any possessions not on their backs (or in storage outside the flooded zone) will be gone. And, thanks to crumbling bridges and landslides, they will be cut off from the east side of the Coast Range for weeks—maybe months.

In other words, if you’re on the coast when the Big One hits, your stay may prove longer than you planned.

What we’ve done Lincoln City, Seaside, and Cannon Beach have moved their schools out of the tsunami zone.

What we should do Relocate all of the coast’s critical facilities outside the tsunami zone and make at least some of them tsunami-resistant. Use hotel room–tax funding to bankroll education campaigns and evacuation plans for tourists. And for you weekenders: pack a lightweight survival kit for your next coastal vacation.