Two Types of Quakes Bigger Than the Big One

Apocalypse Someday: the Big One. (More likely screening here first, however: two types of earthquakes with far lower ratings.)

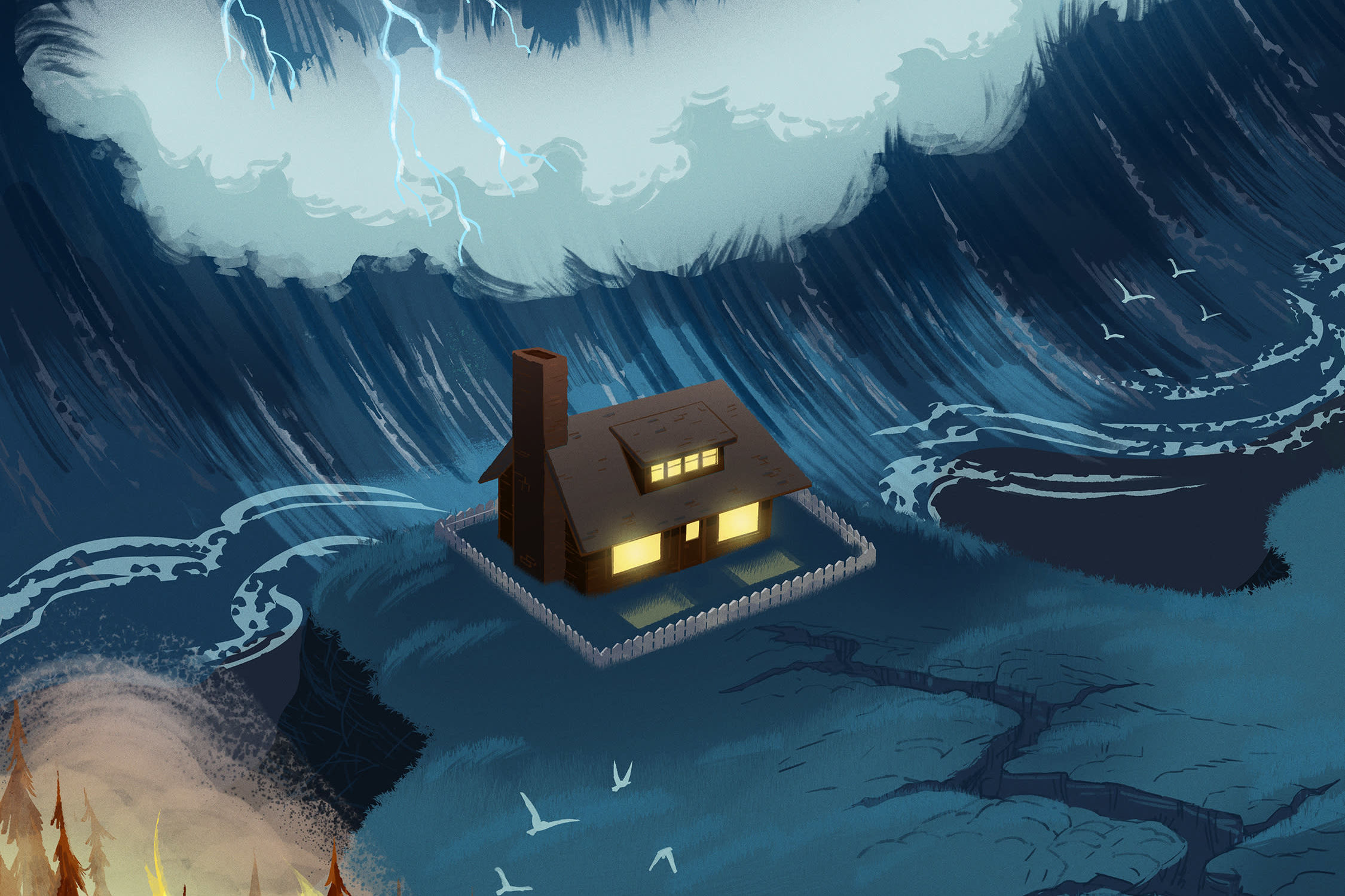

From the New Yorker to this very publication, “The Big One”—shorthand for the epic earthquake that will someday rattle the Cascadia subduction zone for a whopping four minutes—is the Pacific Northwest seismic event that gets the most press. Potentially clocking in at a bridge-crumbling, tsunami-triggering magnitude nine, it’s no wonder this future event has our attention.

But if you really want to prepare yourself for the inevitable, consider listening to retired University of Portland professor Robert Butler. The environmental science expert urges us to broaden our focus to two other types of PNW earthquakes—quakes that occur every decade, rather than the Big One's 243-year-average.) One type, referred to as a "shallow crustal" earthquake, ranges from magnitude three to seven; the other type, a "deep" earthquake, registers between six and seven.

Why should people care about these lesser-magnitude temblors? “What they are missing there is that a shallow magnitude-seven earthquake running across densely populated areas can be devastating,” says Butler. Look to the San Francisco World Series Earthquake (Loma Prieta) in 1989, he says, or 1995's Japanese Kobe Earthquake. Both of these quakes measured a magnitude 6.9, and both resulted in multiple fatalities and billions in damages.

“We know there are two faults [in the metro area]," says Butler, "one on the Portland side and one on the Beaverton side.” Right now, geologists are trying to determine whether or not those fault lines are active (meaning they've moved in the last thousand years) to determine the risk of another quake.

“I grew up in Vancouver, Washington, and remember feeling earthquakes as a kid, but we had this naiveté of not understanding the full measure of our earthquake risk,” Butler says. “When I was an undergraduate student at OSU, half of the faculty in the geology department did not believe in plate tectonics.” In the last 25 years, new information has led the scientific community to accept as fact that great Cascadian subduction zone earthquakes have occurred in the past and will again in the future.

“If we are smart," says Butler, "we can use what’s been learned in Japan and California about building and engineering practices, and build an earthquake resilient Pacific Northwest.” He suggests focusing our energy on constructing building codes that can withstand all three earthquake types, and also giving economic incentives to real estate owners to accelerate updates to the 100,000+ buildings that are not earthquake ready.

To pull an example from our own past, Butler cites Oregon’s shallow “Spring Break Quake” in 1993, which resulted in damages to K–12 schools in Scotts Mills. “Had school been in session when that earthquake occurred,” Butler says, “there almost certainly would have been significant injuries to students in those school, if not fatalities.” This scare provoked statewide upgrades to Oregon building codes, meaning that schools built in the last 20 years or so can now withstand significant shaking. Unfortunately, as Butler points out, there's still much work to be done, with children across the state attending hundreds of schools built prior to 1990. To address that, Butler says, the second part of his May 25 lecture should also prove useful. It's on emergency preparedness, and it's led by Susan Romanski, Mercy Corps' US Director of Disaster Preparedness and Community Resilience.