Strangers on a Train

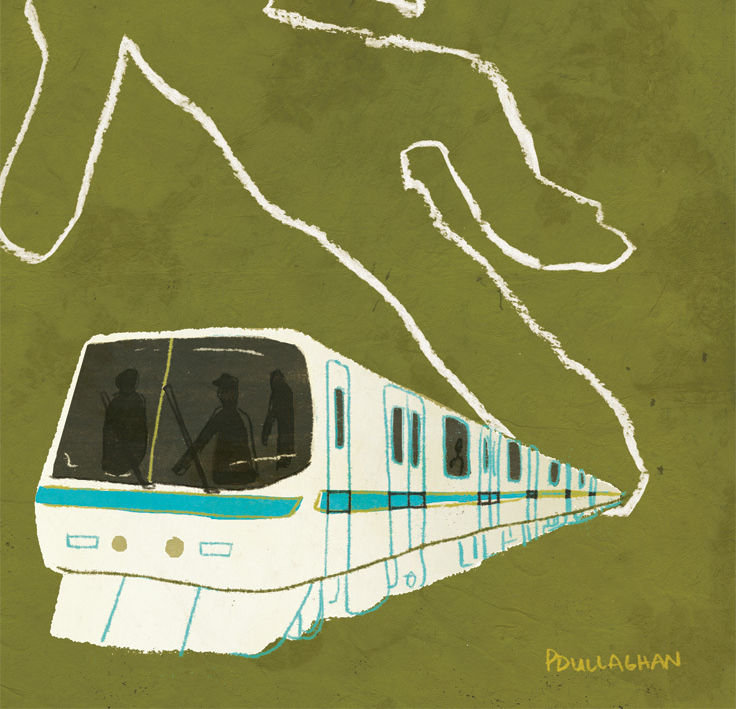

Image: Penelope Dullaghan

THE TRAIN ARRIVES like an angel—an almost empty Blue Line, its warmth a mercy after I’ve been shivering in the November night at Pioneer Courthouse Square. I snuggle into a seat, turn on my iPod and pull out the latest New Yorker—my preferred reading for the daily commute home. The train is only going to Gateway; even so, by the time we reach SW Oak Street, it’s filled to capacity, and I feel that same combination of smugness and guilt that always hits me when I’ve managed to snag a place to sit and am surrounded by people who haven’t.

Later, I will be glad I was seated. A lot of people fell when it happened.

Enough passengers get off at Rose Quarter to create a little breathing room, but it’s still a fairly full car as we glide toward Lloyd Center, then 42nd, then 60th. We’re slipping below the overpass just before the NE 82nd Ave station when the train jerks violently backward, sending people careening against each other. From below us comes a wailing scream of metal wheels on metal rails.

Several people around me scream too. And then the train is still. A minute passes, and then the driver’s voice comes over the speakers: “Ladies and gentlemen, I’m sorry, but the train has hit a trespasser, and I’m afraid we have to stay here for a while. I’m also going to have to turn the train’s power off, so the lights are going to go out.”

We all gasp in unison, as if we shared the same lungs—except the young Asian man sitting next to me. In halting English he asks me what’s happened, and I explain. His brow creases momentarily, and then his expression softens toward patience.

A momentary silence falls over the train, followed by murmurs of “Oh my God,” and then the inevitable speculation. Provided with no information, many of us make wild guesses. “We must have hit his shoulder … It must have been someone who was trying to see if the train was coming… unless he’s under us…”

My neighbor settles into a game of solitaire on his PDA. I stare out the window and become a speculator myself, pondering the term “trespasser.” It makes me think of the sleeping bags I’ve seen along the rail line. A homeless man, maybe, walking along the tracks, hoping to find a dry spot for the night, blinded by the train’s bright lights—and then he’s hurtling through the air, his body already limp as he hits the ground. I blink, watching men in yellow vests walk by outside, and my brain skitters obsessively after them. Are they medics? Coroners?

When the interior lights go out, the darkness triggers in us an urge to speak softly, as if in a movie theater—even those people opening their cell phones to call friends and family keep their voices down. My own phone needs charging, and returning to the art rock on my iPod seems somehow disrespectful, so I eavesdrop on a woman nearby telling her daughter the news over her cell phone: “Stay in the Fred Meyer. Stay together. Don’t let him go off by himself. Go check out CDs.”

Many passengers who’d been standing now sit on the train’s floor, normal rules of propriety having lost their relevance. It’s hard to know how to feel (let alone react) when the train you’re riding hits a person. Should you feel guilty? Hardly. You weren’t driving. (I feel a sudden wave of gratitude toward the train operator, for shouldering that guilt.) But you do feel… involved.

I hear it in the way each cell-phone conversation begins: “I’m going to be late. We hit someone.” Never “the train hit someone” or “the driver hit someone.” Always “we.”

I wonder again about the victim. Was he injured? Dead? Did he see the train coming? We’re near the station—“spitting distance,” as one passenger puts it. I imagine a businessman, briefcase in hand, dinner on his mind. He sees the train pulling in and breaks into a run, overcoat flapping, wind ruffling his thinning hair. I can make it, he thinks, his body feeling suddenly young as he propels it forward in an attempt to cross the tracks before his train arrives.

It takes just a quarter of an hour for the lights to come back on, but it feels longer in the dark. Heat begins pumping up from the baseboards again. I’d picked up milk on my way home, and I find myself worrying that it will go bad.

Finally, the conductor’s voice: “One moment and I’ll have you off the train. As soon as you get off, we’re gonna need to have you make some statements.” A collective groan follows.

Half an hour after the accident, we’re filing onto the NE 82nd Ave platform. The police officers’ questions are perfunctory: name, date of birth, did you see anything? No, of course not. What would we see? What would we want to see? Nevertheless, I find myself staring at the train tracks as I walk upstairs to the street. There is no blood, no body, no chalk line.

At the top of the stairs I pass more officers, then turn. “Is the person okay?” I ask.

“Excuse me?” asks one of them.

“Did—did the person live?”

“No.”

We wait on the overpass for a bus to take us to Gateway, TV cameras harshly illuminating our weary faces. I will myself to be invisible, and the reporters pass me by. Not everyone shares my urge. “Wow, just think: They might put us on TV together!” exclaims a young woman to a matronly woman nearby.

“I kind of hope they don’t,” says the older woman. “I look fat on the screen.”

“Yeah, I’m not wearing enough makeup,” says the first woman.

I don’t want to listen, but I can’t stop. I’ve only lived in Portland for two months, and riding the MAX with my fellow Portlanders was the first thing I’d found to make me feel connected to my new home. But now I don’t feel connected at all. Instead the only person with whom I feel any connection wasn’t even on the train.

In the days to come, I scour the news for coverage and learn that my imaginary vagrant/businessman was, in fact, 48-year-old Susan Dorsey. For a while, anonymous Internet commentators theorize that she was distracted by a cell phone (she didn’t own one), or that she was drunk (she wasn’t), or even that she deserved her fate (yes, someone really did write that). Eventually, an Oregonian obituary portrays her as a kind woman with a long history of volunteer work—and of epilepsy, which rendered her unable to drive. No one will ever know why she jumped that barrier and began walking on the tracks, but her family suspects she was having a seizure.

How should you feel when the train you’re riding hits someone? I still don’t know. I assume none of us do. For the first week after the accident, whenever we slid under that overpass, I paused to look up from whatever I was reading—a moment of silence for a woman I never knew. Now, months later, I rarely do even that. Occasionally I wonder if I’ll recognize someone from that night, but I wouldn’t say anything if I did. After all, no one wants to remember a night like that, the night we—always we—hit a woman on the tracks.