The $150,000 Question

Image: Basil Childers,Basil Childers

TOMORROW, AT NOON on August 15, 2007, Pete Seda will be arrested. Minutes after he steps off a Lufthansa Airbus at Portland International Airport, federal agents will surround him. One, clutching an arrest warrant, will verify Seda’s identity and recite the charges pending against him. Another will ratchet handcuffs around his wrists. Then he will be taken to an unmarked federal van and spirited off to jail.

Pete Seda knows this will happen, yet he still wants to come home.

Since a United States District Court judge in Eugene signed that warrant on February 17 two and a half years ago, Seda, a 50-year-old Iranian-born American whose given name is Pirouz Sedaghaty, has been living as a fugitive in Iran and, most recently, Syria.

Although he does not regret the day in 2003 that he left the United States amid a brewing criminal investigation, Seda deeply misses his life in Oregon. He wants to return to Ashland, where he lived for nearly 30 years, and settle into a house and a routine with his young wife, Summer Rife, a 27-year-old Alaskan whom he met while giving a talk about Islam at Rogue Community College and married while he was in exile. He wants to visit with his two sons (from a previous marriage), 20-year-old Joseph and 23-year-old Jonah, both practicing Muslims who are now living on their own in Portland, where they’ve grown into men without him.

Before he fled the country, Seda made a living as an arborist, pruning trees for the city and wealthy Ashlanders. Every so often his clients might look out their windows to see this hale and bearded woodsman silence his chain saw, face Mecca and bow his head in prayer. This overt display of faith charmed many of them. As one of maybe two dozen devout, practicing Muslims in a community primarily composed of Christians and New Age spiritual devotées, Seda was also charmed by Ashland. Its liberal politics and diversity-embracing ethos allowed him to practice his religion openly and without fear.

So when he chartered the Ashland chapter of the nonprofit al Haramain Islamic Foundation in 1997, no one in town questioned it. After all, Seda was a respected, hardworking member of the community, an upright citizen who was often asked to speak from a Muslim point of view at local schools, churches and synagogues and at public events, including a peace rally that was held in the commons at Southern Oregon University on the first anniversary of the September 11 terrorist attacks. And the mission of al Haramain, as stated in the articles of incorporation Seda filed with the state of Oregon and the IRS, was simply to peacefully advance Islam, just as any church might dedicate itself to advancing Christianity. Al Haramain even went one step further, explicitly opposing “terrorism, injustice or subversive activities in any form.” It provided a place for area Muslims to worship. It sent Korans to prison inmates.

What few Ashlanders realized at the time, however, was that Seda’s house of worship, situated on four and a half bucolic acres near the city’s southern border, also had direct ties to the Middle East. And that the chapter’s parent organization, once one of the largest nonprofits in Saudi Arabia, would eventually be fingered by the U.S. Treasury Department as a fundraising apparatus for al Qaeda.

This they would learn well after Seda skipped town. And after federal agents stormed his home and hauled away more than 60 boxes of evidence. And after Justice Department officials issued a 17-page indictment, charging Seda with conspiracy to defraud the United States government, the filing of a false tax return, failure to report “the international transportation of currency or monetary instruments” and helping a Saudi national named Soliman al Buthe launder a $150,000 donation for al Qaeda’s mujahideen, or Muslim holy warriors, fighting in Chechnya.

Now Seda is penniless and tired of running. And so on August 14, 2007, he has boarded a plane in Damascus, Syria, with a one-way ticket to Portland, via Frankfurt, where he’ll spend his last day as a (relatively) free man.

Image: Basil Childers,Basil Childers

To escort him from Frankfurt, get his bags through customs and bear witness to what inevitably will occur, Pete Seda has enlisted Tom Nelson, a 63-year-old semiretired lawyer who became a Muslim 15 years ago and keeps a small office in a strip mall off Highway 26 in Welches. As one of the few Oregonians who practice both law and Islam, Nelson has become a kind of legal first-responder to those Oregon Muslims who have become swept up in the Bush administration’s war on terrorism. When FBI agents imprisoned Portland lawyer Brandon Mayfield for two weeks and falsely accused him of masterminding the Madrid bombings in 2004 based on a botched fingerprint analysis, Mayfield sought Nelson’s legal advice.

Nelson and Seda meet each other in person for the first time in the international arrivals terminal at Flughafen Frankfurt am Main. Seda, a svelte middle-aged man, 5 feet 8 inches tall and at most 150 pounds, sports a trim, gray-frosted black beard and a disarming grin so broad it creases the crow’s-feet around his eyes. He’s dressed like the laborer he used to be, in canvas pants and work shirt, and pushes a cart laden with three enormous suitcases that contain most of his worldly possessions. Nelson is a white-bearded grandfather in snakeskin cowboy boots and too-large blue jeans that are held above his waist with a braided Indian belt, a “Democracy Now!” baseball cap jammed over his receding gray hair. They clap each other on the back, touch cheeks—first right, then left—in the Muslim gesture of welcome.

“As-salaamu alaikum, brother!”

“Alaikum as-salaam!”

On the plane to Portland, Seda is seated between Nelson and a U.S. soldier returning home from a tour in Iraq. Over the next 11 hours, as the plane crosses the Atlantic and then the United States, the wanted man and the man decked out in combat boots and desert camouflage bond. Seda talks about getting back into the business of pruning trees. The soldier, a minesweeping specialist, pulls out a laptop and shows Seda videos of the roadside bombs he detonated before they could do any harm.

Soon after they touch down in Portland, Nelson and Seda file down the gangway and follow the exodus into immigration, a brightly lit room where bleary-eyed passengers shuffle through a maze of nylon barriers. When Seda hands his passport to the immigration agent, he expects federal officers to swoop down on him. Instead, the agent waves him on.

There’s hope.

Nelson helps Seda collect his suitcases from the luggage carousel, and together they file into the customs queue. It’s beginning to look like Seda just may walk out into Portland a free man. Nelson steps up to the customs officer first, announces he has nothing to declare, and is ordered out of the area when he tries to linger. Arguing that he’s an attorney accompanying a fugitive, Nelson searches for his friend among the sea of passengers’ faces. But it’s already happened.

“Pirouz Sedaghaty? I have a warrant for your arrest…”

Image: Basil Childers,Basil Childers

Who is Pete Seda? To his family and friends in Ashland, Seda’s an innocent man who’s being wrongly persecuted by an administration desperate to legitimize its war on terrorism. Other friends believe he’s a naïve do-gooder who was manipulated by Saudi extremists. To the Saudis he worked for, Seda was merely spreading the peaceful word of Islam. For civil rights activists, Seda’s case represents our government’s willingness to sacrifice constitutionally protected rights in order to safeguard the nation from another September 11-style attack. Experts at counterterrorism think tanks believe Seda’s a legitimate threat—not a bomb-throwing jihadist, per se, but someone who, by knowingly or unknowingly filing a doctored tax return, knowingly or unknowingly funded overseas acts of terror.

It’ll be a jury’s job to sort out these conflicting profiles of Seda, but even after a decision is rendered, we may never know the whole truth. Who is Pete Seda? In many ways, he’s whomever we want him to be.

What most will agree on, though, is that Seda’s story represents a shift in the government’s anti-terrorism tactics—instead of catching terrorists committing acts of violence, you trip them up on financial crimes and starve them of the funds they need to wield power. On that front, the government’s main weapon is Executive Order 13224, a presidential decree that George W. Bush enacted a few days after September 11. This order gives the Secretary of the Treasury Department unilateral authority to blacklist any individual or organization as a “specially designated global terrorist.” Those named to the Treasury’s list—without judicial review, and usually on the basis of secret evidence—have their financial assets seized and have no practical means to appeal the decision. Names are then forwarded to the United Nations al Qaeda and Taliban Sanctions Committee, which summarily globalizes the ban, and requires member nations to likewise freeze the accounts of, and prohibit financial transactions with, these individuals and organizations.

Although Seda himself is not on the Treasury Department’s terrorism list, the Ashland chapter of al Haramain is one of seven domestic Muslim charities that is. All have been shuttered since being added. (Last August, Tom Nelson, who represents al Buthe and the now defunct Ashland chapter of al Haramain, sued the Treasury Department, the Justice Department and former Attorney General Alberto Gonzales in U.S. District Court in Oregon, seeking to have the charity delisted and its assets unfrozen, arguing that the designation process violates the First and Fifth Amendments of the U.S. Constitution.) However, according to David Cole, a constitutional scholar at Georgetown University Law Center, none of the seven U.S. charities nor any individual associated with them has ever been convicted of a terror-related crime. Last October, the government’s case against the Texas-based Holy Land Foundation, which faced 197 terror-related charges for allegedly funding Hamas, ended in a mistrial without a single conviction, an event one former U.S. attorney quoted in the New York Times deemed “a stunning setback for the government.”

Two years ago the government decided not to pursue a court case against the Ashland chapter of al Haramain, but it is intent on going after Seda. To do so, it has resurrected the same antiracketeering tactics it once employed to clamp down on Mob figures like Al Capone, explains Jeffrey Breinholt, the former deputy chief of the counterterrorism section at the Justice Department, where he built the government’s case against al Haramain, al Buthe and Seda. By nabbing suspects on regulatory slipups—like improperly filing tax forms—the government hopes to slow down terrorist activity without having to build blockbuster cases.

“It’s the next phase of our law enforcement efforts against terrorism,” Breinholt says. “We’re not going after them for financing terrorism but for the lies that are associated with it.”

Seda, who pleaded not guilty at his arraignment in August 2007 and vehemently denies that he has any links to terrorism, will face this apparatus at his criminal trial in October 2008. And those who know him say he’s steeled himself for the fight.

“He came back to confront the government with the fact that they are persecuting people who are innocent of any wrongdoing,” says Seda’s longtime friend Paul Copeland, an Ashland civil rights activist. “It’s part of a pattern that’s pretty well documented. The government wants to prosecute and destroy the fundraising capacity of Muslim charities in the U.S. and worldwide. That Pete Seda is a critical piece in that puzzle is preposterous.”

In 1997 Pete Seda was known around Ashland as “the Arborist,” the name he also gave his tree-care service, a thriving business with a half-dozen or more employees and a fleet of trucks. He tended the trees in the city’s signature greenspace, Lithia Park, and elsewhere took pride in saving century-old heritage trees from developers’ chain saws, voluntarily uprooting them with a specialized excavator and then donating them to homeowners for replanting. In 1989, six years before he incorporated The Arborist, Seda also started the Qur’an Foundation. The primary purpose of his home-based nonprofit was to give away copies of the Koran to U.S. and Canadian prisoners, and generally to promote Islam in the Rogue River Valley, where, like most places in Oregon, Muslims make up one-tenth of one percent of the population. (In Jackson County, population 197,000, that’s 197 Muslims.)

Well into the 1990s, Seda’s home, a modest ranch house on acreage near the golf course, served as a gathering place for local Muslims, who came to pray in a spare room on Friday afternoons. One of those worshippers was David Rogers, an Ashland-raised convert who in 1997 spent a summer studying Arabic in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. While there, Rogers met Soliman al Buthe, a Saudi landscape engineer who volunteered at the al Haramain Islamic Foundation, fulfilling requests for Korans from American Muslims. Sure that the two tree-hugging, Koran-donating Muslims would get along, Rogers encouraged al Buthe to pay Seda a visit.

In October of that year, after the two men spoke on the phone, al Buthe flew to Seattle. He rented a car and drove eight hours straight to Ashland, where he booked a motel room. The next morning he met Seda at his home for coffee. Being of similar ages (al Buthe was 35 at the time, Seda was 39) and pursuing similar professions, they also proved to be kindred spirits. By the end of the day, al Buthe had a business proposition: Al Haramain was looking for a partner in the United States to serve as an Islamic-literature distribution hub. It would be far cheaper for al Haramain to send Korans in bulk to Oregon than to send them individually from Saudi Arabia, al Buthe argued.

Unbeknownst to Seda, as early as 1996 the U.S. government had begun investigating allegations that certain international branches of al Haramain were involved in financing terrorist activity. To the Muslim-American arborist, who was inundated with as many as 30 Koran requests a day from U.S. prisoners—orders he had dutifully filled and funded with his own modest income—al Haramain, and al Buthe, must have seemed like a godsend. His mind raced with the possibilities, and over the next few weeks he telephoned al Buthe in Riyadh almost daily. Why stop with literature? Why not open a fully fledged branch of al Haramain that also would serve as a gathering place for Muslims in the Rogue River Valley? No longer would Ashland’s Muslims be relegated to a spare room in the back of his home. With the seemingly unlimited resources of deep-pocketed al Haramain, Seda reasoned that he could make a name for himself by doing good deeds as a Muslim on a much grander scale.

Al Buthe received speedy approval from al Haramain in Riyadh for the project, which by now included not just a distribution center and an unlimited supply of Korans, but also a house—one that would serve as Seda’s residence, al Haramain’s U.S. headquarters and a place of worship for the valley’s Muslim community. From Riyadh, al Buthe would act as treasurer; Riyadh-based al Haramain director general Aqeel Abdul Aziz al Aqil would be listed as president; al Aqil’s deputy, Mansour al Kadi, vice-president. From Ashland, Seda would act as secretary, in charge of managing day-to-day operations. The cash-flush Saudi charity would bankroll everything. (Al Haramain’s worldwide annual operations budget ranged from $30 million to $80 million, depending on the year, and the Ashland chapter would receive $15,000 a month in support.) Soon Seda located a decrepit 4,157-square-foot, 1970s-era split-level on a rolling piece of land just south of town. It had a leaky roof and bad plumbing, but the price was good, only $190,000. Al Buthe returned in December with $206,000 in traveler’s checks for the purchase.

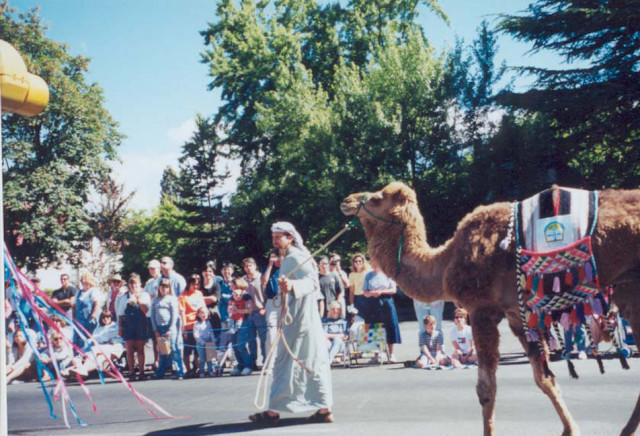

Korans began arriving at al Haramain’s Oregon headquarters by the shipping container. Al Buthe also sent plush blue carpets for the prayer rooms, plus furniture, cushions and a Bedouin tent, which was erected on a hillside above the house. To evoke the Saudi Arabian landscape, Seda planted palm trees and even bought an aging camel from a Portland-area petting zoo for $7,000. He named it Mandub (Arabic for “ambassador”), and the camel, led by an al Haramain volunteer in flowing white Saudi robe and headdress, soon became the star of Ashland’s Fourth of July parade. Schoolkids came to al Haramain by the busload to sit in the prayer house and learn about Islam; their parents came to a similar event, held in the Bedouin tent in the evening, that Seda dubbed “Arabian Nights.” Al Buthe became a regular guest of Seda’s, and Cadillacs loaded with visiting Arabs were a common sight in downtown Ashland, as well as at the Costco in Medford, where al Buthe and his Saudi friends liked to shop.

Bank records show that, over the course of nine trips between 1997 and 2001, al Buthe deposited a total of $778,845 into the Ashland branch of Bank of America, where al Haramain maintained a business account. Al Buthe only withdrew money and took it back with him to Saudi Arabia once, a transaction that has become the basis of the government’s charges.

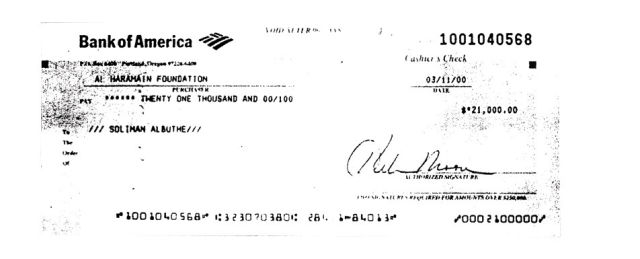

The chronology of events, according to the federal indictment and other court records, began on February 24, 2000, when an Egyptian physician named Mahmoud Talaat El Fiki wired $149,985 (in “support to our Muslim brothers in Chychnia”) from the National Bank of Kuwait in London to al Haramain’s Bank of America account in Ashland. During a trip that al Buthe made to Oregon two weeks later, he and Seda walked into the Bank of America and withdrew $131,300, which they used to buy 130 traveler’s checks worth $1,000 each. Seda then returned to the bank the next day and purchased a $21,000 cashier’s check, which was issued in al Buthe’s name. On March 12, al Buthe left the United States carrying the checks in a laptop briefcase, but at the airport failed to fill out a customs form that’s required of anyone leaving the country with more than $10,000 in cash.

Image: Basil Childers

On the nonprofit’s 2000 federal tax return, Seda indicated that the $130,000 in traveler’s checks that al Buthe had taken back to Riyadh instead had been used to purchase a mosque in Springfield, Mo. The cashier’s check, according to the same return, was refunded to the Egyptian donor.

The IRS contends that the pair conspired to launder the original donation, with al Buthe purposely concealing the money from customs officials and Seda attempting to cover his friend’s tracks by lying on his al Haramain tax return.

Soon after al Buthe returned to Riyadh with the money, Seda and his family joined him in Saudi Arabia for hajj, the annual pilgrimage to Mecca. Al Buthe drove the group in a van to Mecca, where for 11 days the men and boys spent their days in prayer and their nights in tents. They made circuits around the Kaaba—the sacred building that all Muslims face to pray—drank holy water from the Zamzam well and cast stones off the Jamarat Bridge to ward off the devil. By this point, al Buthe was like an uncle to Seda’s children, then ages 12 and 16, and had become a best friend to Seda, who called his benefactor halwa (an Arabic term of endearment that roughly translates as “sweets”).

Pete Seda’s world began to unravel on September 11. Anonymous callers left threatening messages on the answering machine at his prayer house (“You better leave the country while you’re still alive”). Soon after, to demonstrate his personal opposition to the attacks, Seda called the FBI and invited agents to his house, offering to answer whatever questions they might have. David Berger, an Ashland attorney who handled some of the chapter’s legal affairs, attended the meeting. According to Berger, on September 15 two plainclothes agents, one from Medford and another from San Francisco, sat in Seda’s living room.

“Pete offered to make anything they wanted available to them, and they seemed satisfied,” says Berger. But a couple of months later, Seda called Berger to the house and led him down to the end of the driveway and across the road. There he pulled back the branches of some bushes to reveal a hidden video camera that he’d discovered, its lens aiming straight up his drive. “It was upsetting to him that he didn’t have the privacy he was entitled to as a U.S. citizen,” says Berger. “Pete became quite paranoid. He would call and come over, but he wouldn’t talk inside my house. He was convinced it was wired.” Not long after that, Mandub died of kidney failure. Seda believed the animal had been poisoned.

Image: Basil Childers

In August 2002, relatives of the victims of the September 11 attacks filed a $100 trillion lawsuit in U.S. District Court in Alexandria, Va., against more than 80 individuals and organizations they deemed responsible for financing the attacks. Seda and al Buthe were among those named as defendants. The basis for their inclusion in the suit? Investigators hired by the plaintiffs claimed that the business card of al Haramain-Riyadh’s deputy general director, Mansour al Kadi, had been found in the home of a Kenyan al Qaeda operative who had been Osama bin Laden’s personal secretary. Since al Kadi also was listed as vice president of the Ashland chapter of al Haramain, the suit named all four of the Ashland chapter’s directors.

Word leaked. Soon after, a lone protestor began staking out the Mail Stop in downtown Ashland, where Seda rented a post-office box that served as the chapter’s business address. “ALL ARABS MUST DIE,” read the man’s sign. It was too much for Seda.

One day in February 2003, with his tree-pruning business in ruins, Seda knocked on the bedroom door of his oldest son, Jonah. Suitcase in hand, Seda told his son that he was leaving for Saudi Arabia for hajj and was taking Joseph, Jonah’s 15-year-old brother, with him. “I said, ‘Cool, see you in a couple of weeks,’” recalls Jonah, who that month had turned 19 and relished the prospect of living on his own for a short time. As it turned out, he would not see his father on U.S. soil for four and a half years.

At 7 in the morning nearly a year later—February 18, 2004—with his father and little brother now living in the United Arab Emirates, Jonah was in his bedroom at the prayer house, knotting his tie in preparation for an interview for a teller position at a local bank, when the doorbell rang. He opened the front door and stared, mouth agape, at more than two dozen FBI and IRS agents, as well as officers from the Jackson County Sheriff’s Office and Oregon State Police. Some of them wore body armor and had their guns drawn. Colleen Anderson, an IRS special agent, handed Seda’s son a search warrant allowing her team to seize evidence pertaining to the investigation into whether his father and al Buthe had committed tax fraud and conspired to smuggle money out of the United States. Jonah frantically dialed Berger; over the next six hours, the two men watched as agents ransacked the house, filling an unmarked utility truck parked in the driveway with evidence and leaving behind red-clay footprints on the prayer room’s blue plush rugs.

Less than three months later, on May 6, the FBI arrested Brandon Mayfield and charged him with the Madrid bombings. Evidence used to justify his arrest included a phone call someone—neither he nor his wife remembers making the call—placed to Seda using Mayfield’s wife’s cell phone. Four months later, the Treasury Department froze the assets of the Ashland chapter of al Haramain and of al Buthe, naming both him and the nonprofit to its “specially designated global terrorist” list.

Soon after that announcement, Charles Carreon, a public defender who once tutored Seda as a fellow student at Southern Oregon State College in the 1980s (Seda’s dyslexia was so bad, Carreon says, that he ended up just typing Seda’s term papers while Seda dictated) and did legal work for Seda’s arborist business, staged a silent protest in Ashland’s main public square. The sign he held was labeled “TERRORIST LIST,” with a photograph of Brandon Mayfield, another of Seda, and a silhouette labeled “YOUR NAME HERE.”

At Pete Seda’s detention hearing at the Wayne Lyman Morse United States Courthouse in Eugene on August 22, 2007, a week after his surrender, a jangling of leg shackles announces the returned fugitive’s entrance into the main courtroom, a cove-lit ultramodern parabolic chamber with walls of terraced cherrywood. Dressed in loose-fitting prison greens stenciled with the words “LANE COUNTY JAIL,” Seda grins effusively and waves at his sons, who are seated in the front row. The gallery’s packed, even though this isn’t a trial. It’s just a hearing to determine whether or not Seda will be released while he awaits his October 2008 jury trial. Typically, a detention hearing involving charges of irregularities on federal tax and customs forms is a nonevent: The judge sets conditions of release and the date of trial, and then frees the prisoner, a process that more often than not is over in a matter of minutes. Today’s hearing, however, will last more than five hours.

The government has staked out territory on the left side of the room, where the pewlike benches are packed with FBI and IRS agents, many of whom participated in the prayer-house raid. Nearby sits U.S. Attorney Karin Immergut, the ranking Justice Department official in Oregon, who made the two-hour drive from her office in the Hatfield Federal Building in downtown Portland. Police detectives in Portland call Immergut “the Stalker,” for the tenacity with which she pursues an investigation, although most people remember her as the woman who grilled Monica Lewinsky before the grand jury investigating Bill Clinton (impassively asking questions like “And on that occasion, did you perform oral sex on the President?”) Although Immergut says she’s in the gallery as a boss observing her staff at work, her presence in the courtroom sends a clear signal that the Justice Department deems Seda’s case to be a high priority.

On the right side sit Seda’s family and supporters, mostly a motley array of hippyish, middle-aged Ashlanders, but not without their own celebrities: Brandon Mayfield and his wife, Mona, walk in at the last minute. Although Mayfield has never met Seda, he says he came to show his support to a Muslim brother, “another one of those unlucky people who’s probably been falsely accused,” as he later put it.

With his bushy salt-and-pepper moustache and rumpled charcoal suit, Portland defense attorney Larry Matasar is the man who will try to convince Judge John Coffin that Seda is not a flight risk or a threat, and should be released on his own recognizance. The job of U.S. Assistant Attorney Christopher Cardani—who sports a military—style crew cut, designer eyeglasses and an immaculately pressed suit—is to convince him that Seda is a danger to the community and thus should remain behind bars until the full trial.

Talk to any of Seda’s supporters in the courtroom, or to the many others following the case, and they’ll tell you that Seda is the last person any Ashlander would deem a threat to the community. “Not only was he personally opposed to violence,” says Ashland attorney David Berger, “he believed terrorism was inconsistent with Islam.”

The picture Berger and others paint is of a man who started his life at a disadvantage: an Iranian-born teenager who fled persecution in the Shah’s Iran in 1976 to live with one of his brothers in Ashland, where he came of age during the height of the Iranian hostage crisis, when Iranians were vilified and he was one of the only ones in town. In response to the prejudice leveled at him when he was an undergraduate at Ashland-based Southern Oregon State College (now Southern Oregon University), Seda convened a public forum and attempted to explain the actions of his countrymen during the 444-day U.S. embassy takeover, which began in 1979. “He was trying to defuse some of the hatred leveled against Iranian-Americans, and challenge people to overcome their hostility,” says his friend Paul Copeland, who notes that Seda played a similar role on the first anniversary of the September 11 terrorist attacks, speaking as a Muslim emissary at an antiwar protest. “That’s Pete Seda: always trying to settle a dispute.”

With al Haramain’s resources, Seda tried to take his mediation skills onto the world stage. David Zaslow, the rabbi of Ashland’s Havurah Shir Hadash synagogue, still laughs at the chutzpah of an ill-conceived plan Seda hatched to end the Palestinian-Israeli conflict in the summer of 2002. He’d hoped to hire Jewish truck-drivers and lead a convoy of trucks laden with food from Jerusalem across the border into Palestine, where he’d distribute the goods to refugees. “It’s an anecdote that speaks to his sincerity, and perhaps his naïveté,” says Zaslow.

Seda flew to Jordan and tried to talk his way through the Israeli checkpoint, a Muslim with only a letter of support from Rabbi Zaslow in his pocket. He was turned away after hours of interrogation.

One thing makes the rabbi wonder, though: According to Zaslow, Seda said he would be taking $150,000 with him to buy the food. “I wasn’t surprised by the indictment, because I knew Pete had made at least one attempt to give away $150,000,” says Zaslow. “I was surprised that he got himself into trouble trying to give it to Chechen rebels. That’s not a group you want to be giving money to. If I gave money to Hamas because Hamas is running a hospital, it would be naïve for me to think that I wasn’t giving to a terrorist organization. I can believe Pete may have been naïve and I can believe he made a terrible mistake, but I cannot believe that he was one person in public and another in private.”

Glenn Thatcher, a friend from Coos Bay who considers Seda to be “like a brother,” says Seda’s dyslexia often made him “stupid with money” and believes his friend may have been used unwittingly by al Haramain. “An honest person gets taken advantage of by a crook, because an honest person doesn’t think like a crook,” says Thatcher. “The real world shoots you in the back of the head and leaves you in a ditch. Pete doesn’t want to believe the world’s this way.”

The shoot-you-in-the-back-of-the-head real world walks into the Eugene courtroom that day, in the person of Daveed Gartenstein-Ross. If attorney Christopher Cardani wants to portray Pete Seda as a menace to society, he couldn’t have asked for a better witness than Gartenstein-Ross, whose 2007 memoir, My Year Inside Radical Islam, portrays Seda as “the ultimate con man,” a Muslim extremist hiding behind the public façade of a pacifist.

Gartenstein-Ross grew up in Ashland and spent a year between college and law school in 1999 working as Seda’s “deputy administrator” at al Haramain. His responsibilities included everything from filing weekly dispatches to the head office in Riyadh to mailing copies of the Saudi Arabian Noble Qur’an to U.S. prisoners. The FBI informant (who converted to Christianity in 2000 after leaving al Haramain and is now a research analyst at a Washington. D.C.-based counterterrorism think tank) looks nothing like the bearded radical of his Ashland days. He’s as polished as the prosecution, and walks stiff-legged to the witness stand.

His testimony lasts nearly an hour, much of it taken to explain Wahhabism, a conservative strain of Islam that’s prevalent in Saudi Arabia and that, he says, formed the basis of the literature he distributed on behalf of al Haramain. Wahhabism is distinguished by a controversial interpretation of the concept of jihad (holy war) that some believe requires Muslims to spread their faith by force. At one point, Cardani hands Gartenstein-Ross an excerpt from the appendix in one of the Noble Qur’ans he mailed out while working for Seda.

“‘Allah made the fighting obligatory,’” Gartenstein-Ross reads. “‘To get ready for jihad involves various kinds of preparations and weapons. Tanks, missiles, artillery, airplanes…’”

To underscore the notion that Seda actually participated in the spread of the violence he advocated, Cardani asks Gartenstein-Ross to tell the court about a speech that Seda delivered at the Ashland prayer house upon returning from hajj in the spring of 1999, at the height of the conflict in Kosovo, when the mujahideen’s Kosovo Liberation Army was battling forces loyal to Serbian dictator Slobodan Milosevic.

“Pete said he knew a couple of individuals who were going to go over to fight against the Serbs,” says Gartenstein-Ross. “He encouraged us to give money for this.”

Cardani, referring to “Exhibit K,” a receipt for a $2,000 wire transfer from Seda’s business account to the bank account of the al Haramain branch office in Tirane, Albania, declares: “That office was later designated by the United States, and as well by the United Nations, as a terrorist-supporting organization.”

To reiterate that all of this is connected to what Seda’s actually being charged with, Cardani asks Gartenstein-Ross to testify about Seda’s pro-Chechen sentiments, bringing up Egyptian Mahmoud El Fiki’s $150,000 donation in support of “Muslim brothers in Chychnia.”

After the final arguments, Judge Coffin sighs: “Well, to say the least, this has been a most unusual detention hearing.”

On September 10, two weeks later, Judge Coffin is expected to announce whether he will release Seda on bail. This time there are fewer people in the courtroom: It’s just Seda’s boys sitting in the front, along with their stepmother, Summer Rife, who’s wearing a hijab and burka; Seda’s two brothers, who live in Oregon; lawyer Tom Nelson in a yellow-and-white-striped tie and dark suit; and a few friends, including Copeland and Thatcher. Seda looks hopeful.

Judge Coffin lectures Cardani and says that after hearing testimony from Seda’s friends in Ashland, he doesn’t believe the government’s argument. He orders Seda’s release. Out in the hallway, there’s hugging and congratulations. But the celebration proves to be short-lived. Two hours later, the court reconvenes, and Cardani approaches the bench.

“With all due respect, I have never appealed an adverse decision in this court in the 15 years I’ve been here,” says the Department of Justice prosecutor. “I’ve had consultations with my direct supervisor and with the U.S. Attorney. And respectfully, it’s the government’s desire to seek a review by Judge Hogan.”

Judge Coffin harshly reiterates his ruling for the record, but despite his opposition, judicial process requires him to allow the case to be reviewed by the court’s senior judicial official, chief Judge Michael Hogan, a conservative U.S. District Court judge. Seda is led out of the courtroom and returned to his cell at the Lane County Jail, where he’ll remain behind bars for nearly four months, until Hogan, in agreement with Coffin, finally signs his release on the last day of November.

Meanwhile, back in Portland, his sons are dejected. At the Stumptown coffee shop in the bottom of the Ace Hotel, Jonah, a goateed auto-repair student at Portland Community College shrouded in Mountain Hardware fleece, says he’d struggled to keep his composure when he went to visit his father in jail, speaking to him on a telephone, separated by bullet-proof glass.

“It makes me so sad—someone who’s dedicated his life to helping others, and I have to see him like that through a glass pane,” says Jonah. On the other side of the window, he says, his father smiled back at him, saying, “I love you. Everything will work out.”

In Riyadh, Soliman al Buthe has endured his own share of hardships. Not long after the September 11 attacks, he was summoned to the Saudi Ministry of the Interior, where he was interrogated about his travels to Ashland and the money he brought in and out of the country. In the spring of 2002, he resigned his volunteer position at al Haramain, because, he says, he wanted to spend time with his family after his 4 1/2-year-old son, Muhammad, died of a heart defect.

Al Buthe says he read about the Ashland prayer-house raid in the newspaper but dismissed it as a scripted Hollywood drama. It was his Washington lawyer who sent him an e-mail link to the Treasury Department’s September 9, 2004 press release naming him to the global terrorism list. When he read that the United States intended to, as the release stated, “excommunicate [him] from the worldwide financial community,” al Buthe laughed out loud and deemed the act an election-year political ploy designed to boost President Bush’s approval rating. The only fallout, al Buthe says, was that he had to collect his $4,000-per-month salary in cash, since his bank account was frozen. The Saudi government has also forbidden him from traveling abroad, for his own protection. He cannot answer the charges levied against him, he says, because in the United States, he can’t get a fair trial.

Given that al Buthe can’t travel to Oregon, I decide to travel to al Buthe. I want to hear his side of the story, but what I’m really looking for is a deeper understanding of the alleged global terrorist who set in motion the course of events that put Seda where he is today. And so on a warm October night in Riyadh, after an introduction by Nelson, I call on al Buthe at his favorite hangout, a Bedouin tent he’s erected in a walled compound just behind one of the city’s soccer stadiums.

Bright fluorescent light spills onto the patchy lawn outside (which doubles as a soccer field), and a neat row of men’s sandals line the grass near an open flap that serves as the entrance. Inside, it’s carpeted with luxurious Persian rugs. Lining the interior walls are a water cooler, a brick fireplace and a refrigerator stocked with Sprite and bottled water. Several couches and recliners and chairs are arranged around the perimeter of the room. Sitting on them is al Buthe’s posse, a half-dozen middle-aged men, all dressed in floor-length robes. There’s Adel (an electrical engineer for the Saudi Electricity Company), Saleh (a colonel in the Saudi army), Achmed (a general at the Saudi military academy), Abdul (an executive at Saudi Aramco, the Kingdom’s largest oil company) and Muhammad (a linguist at the Arabic Languages Institute). Some are reading Arabic newspapers or English books, among them Dead Certain: The Presidency of George W. Bush and The Looming Tower: Al Qaeda and the Road to 9/11. Others have laptops and are surfing the Internet, and everybody has at least one eye on the wide-screen satellite TV. There’s also a butler, Babuna, a scrawny Filipino in his 20s who makes coffee spiked with sugar and cardamom for the men, and keeps everybody’s little porcelain cup filled.

Sitting on a gilded, velvet armchair, like a prince on his throne, is al Buthe. Like everyone else, he’s wearing the traditional Saudi flowing white robes and red-and-white checkered headdress. He’s athletic enough that he played on the Saudi national basketball team in his college days, and the rangy, middle-aged civil servant, who sports a long, wiry salt-and-pepper beard, still competes in a weekly citywide tournament, where crowds cheer for “Speedy Soliman.” Since his designation as a terrorist, al Buthe has been twice promoted by the City of Riyadh, and now the former landscape engineer serves as general director of its environmental health department, where he oversees a staff of 500—on the day I arrived, he personally led a raid on a Mr. Crispy hot-dog vendor for reusing the oil in a deep-fat fryer. His sense of humor might best be described as wry. “We have power; we have Internet as well,” al Buthe shrugs. “It is a high-tech tent.”

This isn’t just a tent. Given the wattage of the characters in the room, it feels more like a think tank. And it’s obvious, considering the reading material and the TV (which switches between CNN, C-SPAN and MSNBC), that these Saudi elite know more about American politics than most Americans do.

There’s a Knicks game on at the moment, but during a commercial, one of the men flips through the channels, and President Bush briefly appears on the screen. “Wait! Go back!” someone yells. It’s a White House press conference on MSNBC, and Bush is rebuking the press corps for recent coverage criticizing the CIA’s methods of interrogating terror suspects. Bush notes that information gleaned from these practices helped thwart terrorist attacks abroad and at home. “Despite the fact that our professionals use lawful techniques, the CIA program has come under renewed criticism in recent weeks,” says Bush.

A chorus of jeers erupts from the couches.

“Those who oppose the war on terror need to answer this simple question: Which of the attacks I have just described would they prefer we had not stopped?” Bush adds.

Al Buthe rummages around and finds an “IMPEACH” bumper sticker that Tom Nelson, who’s also here, has brought from a Portland anti-Bush rally. “By the way, this is very important. I’m not anti-American,” al Buthe says. “I don’t have a problem with American culture or freedom or American way of life. But I do have a problem with the Bush administration. I’m anti-Bush.”

What I’ve brought al Buthe is a satchel containing photocopies of all of the government’s exhibits from Seda’s hearing. Since he’s a co-defendant, I ask if he can speak to the charges. He invites me to sit down on a chair across from him and pulls a file at random. It’s the excerpt from the Noble Qur’an and the “Call to Jihad” appendix that Gartenstein-Ross had recited to the court.

“What does the American Constitution say?” asks al Buthe. “That Congress cannot interfere with the free exercise of religion. What does Mr. Cardani know about the call to jihad? This doesn’t mean you wage a war. The West and America have this phobia, fear of jihad, fear of mujahideen. They don’t know what’s the jihad. It’s the service struggle, the internal struggle between doing good or evil. Mr. Cardani cannot judge these things.”

I continue to push him, but more often than not, his answers depend on mere degrees of interpretation. When I ask him flat-out if he’s a terrorist, he asks, “Do you think if I’m a terrorist, my government will let me live a happy life?” Then he notes that his government wouldn’t have hired him to police the environmental health of some 5 million people in Riyadh if he were a terrorist: “If I want to do something, I can damage the whole city.” When I point out that the Noble Qur’an’s militaristic interpretation of jihad—which calls for “tanks, missiles, artillery, airplanes”—can hardly be deemed as an internal struggle of conscience, al Buthe claims he didn’t know about that passage at first, and that in 2001, he replaced the Noble Qur’ans that al Haramain was distributing with a more mainstream translation.

As for the conspiracy and money-laundering charges, al Buthe tells me that as treasurer, he felt it was his responsibility to collect the donation, given its size, and to personally bring it back to Riyadh, where he deposited the checks into his own bank account and then handed the money off to al Haramain’s financial director, Khalid bin Obaid Azzahri, who forwarded the Egyptian’s donation to a Russian agency set up to distribute aid to refugees in Chechnya.

Al Buthe hands me an affidavit signed by Azzahri and a copy of the agreement establishing the Russian aid agency signed by the Saudi Kingdom’s deputy prime minister, but I have no way of gauging the authenticity of the documents—or, for that matter, verifying anything he has to say in his defense. Much like the U.S. government’s case against al Buthe and Seda, everything al Buthe says sounds plausible, but there’s little in the way of actual proof. As for failing to declare the money, he says it was an honest mistake—that he wasn’t even aware that he was supposed to fill out the customs form, since the documents aren’t distributed prior to boarding.

And that botched tax return Seda filed? Al Buthe attributes the error to an honest mistake as well. “He is a very simple man,” says al Buthe. “That guy, he have a clean heart. He can sit down with anyone and joke. He doesn’t have any problem with anybody. If you know Pete, you love him.”

I ask al Buthe how well he knows Aqeel Abdul Aziz al Aqil, al Haramain’s founder and general director, who also served as president of Seda’s chapter and was added to the terrorism blacklist, for allegedly using al Haramain to benefit himself and al Qaeda.

“I used to spend only one or two hours a day with him,” al Buthe says. “If you want to know somebody, you have to travel with him. You have to eat with him.”

Over the course of four days in Riyadh, I do just that with al Buthe. We hang out at coffee shops and restaurants, drive into the desert and onto rust-red sand dunes. I watch him play basketball in a city tournament on a court that’s still owned by the family of Osama bin Laden, and each day ends with a feast in his tent, where we stay up until 2 in the morning, high on sweet Arabic coffee, debating religion and politics and watching CNN and the Arabic news network al Jazeera. I’ve traveled with Soliman al Buthe. I’ve eaten with Soliman al Buthe. But still, I don’t know him.

I know someone in the United States who thinks he does: Jeffrey Breinholt, the Justice Department official who’s on sabbatical as a senior fellow at the International Assessment and Strategy Center, another Washington, D.C., counterterrorism think tank. Later, when I mention to Breinholt that I’ve met with al Buthe, and note that the guy seems honest and not necessarily dangerous, Breinholt tells me that I’ve failed to grasp a fundamental tenet of counterterrorism. “Not every person who is designated as a terrorist is a bomb-thrower,” he says. “Some occupy a position within the al Qaeda world that aren’t your traditional jihadists with masks and guns. That’s not what they do. They’re financial types. White-collar guys.”

Still, during my time in Riyadh, I grow genuinely fond of al Buthe. I understand how Seda could have fallen in with him, especially when, just before I leave al Buthe’s tent for the airport, I ask if he feels personally responsible for what has happened to his friend.

“I feel sorry for him,” al Buthe answers quietly. “He is a good man and he is going back to prove that he is a man of peace. Sometimes, when you face such calamities, God is testing you, like he tested the prophets, to see if you have the patience. It increases the faith and brings you closer to God.”

On a December afternoon, more than 15 weeks after Pete Seda’s arrest at the Portland International Airport, my photographer and I board a plane at PDX that’s headed to Medford. The night before, Judge Hogan had finally relented and released Seda from the Lane County jail in Eugene on $58,981 bail. He was under house arrest at the home of Paul Copeland, who lives in a tightly packed subdivision tucked into the hills above Lithia Park. I knock on the Copelands’ door and there he is, the man I’ve been waiting to meet for some four months.

“Hello, I’m Pete.”

He stands in the hallway smiling warmly, arm and hand extended, eyes crinkling. His voice is soft; his chinos conceal his leg monitor. Our photographer wants to shoot Seda’s portrait in the yard, to catch the twilight, but Seda refuses to step outside.

“So many reporters were sitting here last night when I arrived,” he says. “All the [camera] flashes were going off.”

Instead, he sits for his portrait at the dining room table while I talk to his wife, who gushes, “Just look at that guy!” Rife had been living in Portland, but now is a guest at the Copelands’ and hopes to stay in Ashland. But that all hinges on the outcome of the jury trial in October.

I ask Rife how Seda’s return and subsequent hearings have affected her.

“It makes me care more about justice and rights,” she says. “I think most people, myself included—and I’m ashamed to say it, because I never knew it until recently—but most people don’t care unless it happens to them. I’d like to say I’m the kind of person who would care no matter what, but it took…”

Her voice breaks and she looks away.

Defense attorney Larry Matasar has forbidden me to interview Seda. I can’t ask him about his views of jihad. Or if he ever questioned al Haramain’s motives. Or if he knows precisely where the $150,000 donation ended up. We’re only reluctantly allowed a photograph, and then I’m told it’s time to leave.

While the photographer packs his things, I ask Seda how it feels to be free. He thinks for a moment.

“It feels good,” he says. “To have some semblance of humanity again. In there, it’s kind of a cuckoo’s nest.”

Rife’s cell phone rings—the tone is an Arabic dirge that she says reminds her of a cab ride she took while visiting her husband when he was still a fugitive living in Damascus, Syria. It’s Tom Nelson calling, wondering how the photo shoot’s going.

Probing the limits of my visit, I ask Seda to tell me what it was like to walk out of jail. His response takes the form of a well-folded scrap of paper, a worried copy of the prepared statement he’d distributed to the reporters and photographers who had mobbed him earlier. It says, “I apologize but I cannot make comments about my case during the period preceding the trial. I voluntarily returned to the U.S. to face my accusers. I hope that I will have a fair chance to prove my innocence.”

Seda smiles wanly.

“I wish I could be of more help; please forgive me,” he says. “The thing is, I want to tell you; I love to talk. My attorney tells me I’m a loose cannon and right now there is more at stake than opening everything up to the world. I wish I could be a better host. I wish we could have a good time. When all this is over, we are going to do some fun stuff together, inshallah.”

God willing.

The Photographer and I drive down from the hills and head south out of town on the Siskiyou Highway, a narrow strip of asphalt that parallels the interstate. The road opens onto rangeland, and soon we come to a mailbox with the address I have on a copy of IRS special agent Colleen Anderson’s 2005 search warrant affidavit. Up the hill from the mailbox I see it: the former al Haramain prayer house, which turns out to be a rather ugly wedge-shaped ranch jutting out of the hillside above a fenced pasture. We grind up the long, sloped asphalt drive and park next to the garage. Nobody’s home, but a few minutes later, a car pulls up and out steps Martha Feil, a pretty 60-year-old woman wearing a knee-length leather coat over a hoodie and sweatpants. Her friend Margot Schmidt, a woman in her 50s, pulls up the drive next, towing an overloaded trailer. Schmidt begins shuttling boxes into the garage. It’s moving day. They’re renting until May, when they take ownership of the property.

I ask Feil if she’s aware of the history behind this place. She laughs and tells me of course, everybody does—that most people believe there’s a stash of gold coins buried somewhere on the property and have been urging her to buy a metal detector.

“I have a strange interest in this because I’m a retired flight attendant who flew for United for 32 years,” Feil says, noting that she was so affected by September 11 that she asked to be grounded and worked for a while as a counselor for other attendants too afraid to fly. Eventually she quit altogether. “I flew Flight 175 all the time, the one that was flown into the World Trade Center on 9/11.”

Feil points uphill.

“That’s a Bedouin tent. Do you want to go see it? It’s really neat! We call it the camel house.” She scrambles up the hillside, where there’s a miniature circus tent, much like al Buthe’s, perched atop a wooden platform; inside, the plush carpeting’s damp and smells of mildew. She’s planning on using the space as a yoga studio.

Then Feil ducks outside and points to a dead palm tree with a rope tied around it. “That’s the camel’s bridle right there, attached to that palm tree.”

She takes us inside the house and shows us the former prayer room, a sunken living room with a massive pane of glass overlooking the pasture and the Cascades; and the master bathroom, which Seda retrofitted with six washbasins for wudu, the before-prayer cleansing ritual.

Feil stands in the living room with her hands in her pockets. I ask her what the mood is in town, whether folks are sympathetic toward Seda or not.

“I hear more people saying they don’t believe the government,” she says, but notes that that’s partly because Ashland, like Portland, tends to be liberal-leaning. “I’m not that way, because of my connection to 9/11. I just, I just don’t know. I think about [the situation] a lot and it kind of bothers me.”

She shows us outside and stands in the driveway, regarding the withered palm tree and the dead camel’s bridle. “But it is kind of neat that it all came together like this. The day we move in is the day he gets out of jail? I don’t ever want to meet Pete Seda. I mean, if he really had anything to do with the terrorist activities…. It’s gone from him to a United flight attendant who used to work on one of the planes that flew into the World Trade Center. We figure it’s full circle now.”

On our way out, we drive past the bushes that concealed the mysterious camera and out onto the interstate, north to Medford, retracing the route Soliman al Buthe drove so many times in his rented Cadillac. At Medford’s one-gangway airport, our photographer’s camera bag tests positive for explosives as it goes through the scanner. After hand-inspecting the camera, sending the bag through the scanner again and patting down the photographer, the security officer sheepishly apologizes that he’s just doing his job, that the darned machine often gives off false positives.

Once we find our seats on the commuter plane, its turboprops thrum the fuselage, and we’re hurtled through the nighttime sky on the last flight out of Medford bound for PDX, where this story began. A story that—in my mind, at least—never really ends.