Made In Portland

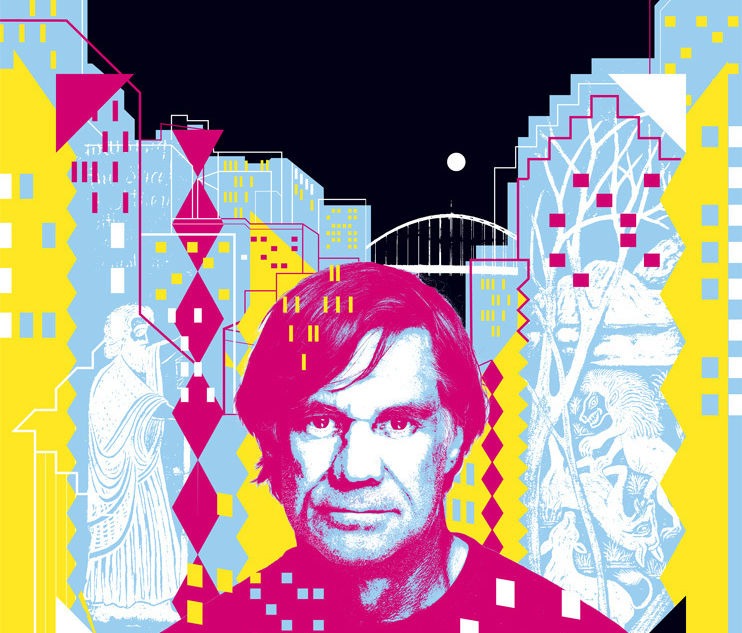

Image: Thomas Cobb

Why Gus Van Sant insists on living in the Pearl District, I haven’t a clue.

The director who made junkiedom an aspirational vocation and made heartthrobs of male prostitutes doesn’t seem to belong among the well-coiffed, caramel macchiato–addicted nouveaux riches of Portland’s most polished neighborhood.

And yet here he comes. Head down, hands shoved into his pockets, briskly crossing the street from his high-rise apartment to the glassed-in minimalism of Isabel’s, an upscale cantina on NW Tenth Avenue. At fifty-six, Van Sant looks like a best-case-scenario incarnation of your dad, with a lightly lined face and the build of a man ten years younger, scuffed red sneakers adding a touch of panache.

The director du jour—in the spotlight for his latest movie, Milk—looks unexpectedly normal. Each time he forks up a bite of his avocado scramble, he tediously breaks up the cheese strands with his fingers and piles them back on top of the utensil. The sight tempts me to make something of the fact that even though most folks know Van Sant as the director of mainstream fare like the Academy Award–winning Good Will Hunting and Sean Connery’s turn as a reclusive author in Finding Forrester, his twenty-four-year, fifteen-film career has been mostly about the messy, sticky bits. I’m talking about hustlers, murderous news anchors, suicidal rock stars. And now, with Milk generating Oscar talk, Van Sant once again submits to being hauled shrugging and mumbling from his home and into the limelight, something he seems to enjoy about as much as passing a kidney stone.

Portland Monthly: Do you have any trepidation about Milk being nominated for an Oscar?

Gus Van Sant: What does “trepidation” mean?

PM: You know, are you concerned about it at all? Being nominated or having to make a speech? Parties?

VS: I’m not an awards person. It can be fun, but I’m not a great winner. If I win, I don’t celebrate. I feel bad for the people I beat. In fact, if I don’t win I feel better. I really don’t like those things, those banquets and honors.

PM: Because you’re foisted into the spotlight?

VS: No. It’s more that you’re just sitting there at this banquet table. Somehow that forum isn’t that exciting. They should change it up.

PM: You moved to Portland twenty-seven years ago, when you started working on your first feature, Mala Noche. I know you moved here with your family in your teens, but why come back?

VS: I lived in New York for three years, LA for six years. I never got anything going there, and it was just easier to do a low-budget film here. I knew places where I could find help and equipment. Also, the Mala Noche story was set here. I wasn’t made to work in a big studio. Besides, I wanted to spend more time here. [Portland is] the first and only city I’ve lived in that had a sort of world unto itself, where, you know, the great-grandparents, grandparents, and kids all live in the same place—the whole universe is here for those people.

PM: What kind of reaction did you get from your industry friends when you moved here?

VS: They thought it was weird. One guy asked me, “What’re you gonna do, take acid?” That’s all people knew about Portland then: Ken Kesey.

PM: Has the art scene changed much since the mid-’80s?

VS: Back then there was the Storefront Theater. It was very radical, sort of antiestablishment. Ric Young was one of the directors, and he was very outrageous. Hank Pander, a painter who’s still around. I was never on the inside of that, though. I always felt I missed the cool circles. I went to the Rhode Island School of Design with David Byrne. I saw his first show with his classmate Chris Frantz. It was a school dance on Valentine’s Day. Then they went to New York and became the Talking Heads. I was in England in 1975, living in a warehouse where the Sex Pistols played their first show—after I left. I lived on Hollywood Boulevard, right down the block from where the LA punk scene was happening. But I wasn’t a punk rocker; I was more of a non-clubgoer. Here in the Northwest all these things were happening with Nike and Microsoft. I remember in like ’71 or ’72 I saw this guy I knew named Mike Slade wearing a pair of Nikes. I said, “Cool, you have your name on your shoe.” He was like, “No, these say Nike. Not Mike.” He became an early Microsoft employee and went on to run things for Paul Allen. He knew early on that something like that was worthwhile.

PM: And you think you lack that foresight?

VS: Yeah, I do.

PM: But you’re still in Portland, which seems like a forward-thinking move.

VS: Yeah, and I go to places like this [Isabel’s]. I’m very uncool. I live in the Pearl. That’s not cool, either. It’s a created community. Originally everybody who lived here were people whose kids had grown up or were divorced. In my building recently a lady got off the elevator—she’d just seen someone with a baby in their arms—and remarked, “I didn’t know we had any babies in the building.” We have three hundred units, and she was unaware any babies existed.

PM: You wore a Mary’s Club jacket for your cameo on the season finale of Entourage. Were you giving them a shout-out?

VS: When I’m in LA, I wear it. I knew it might get on camera, but usually when you wear something intending it to be on camera it never happens. In this case, it did.

PM: So many of your movies are filmed here. Do you ever feel like you had a hand in giving Portland its “cool” status and that you are therefore responsible for the traffic piling up on I-5?

VS: I wouldn’t say I’m arty or involved in any certain scene. I think maybe some of the kids that come, it may have started with some of the films I made. But after a while I think people want to come here because Sleater-Kinney is here, or Stephen Malkmus—the bands have really started bringing people in. Besides, I hear Madison, Wisconsin, is the new film center of the world.