The Parents’ Survival Guide

WHEN YOU FIRST reluctantly handed him over to his kindergarten teacher, your heart pounded as you wondered: Will he make friends? Should I remind the teacher about his peanut allergy and tell her that he’s left-handed? But years from now, when he strides across a garland-strung stage, graduation cap atop his much older, wiser head, you’ll wipe the sweat off your brow for the first time in 18 years. You’ll breathe a sigh of relief. And you may even tear up a little. After all, the fact that your child is standing there, diploma in hand, is largely because of you.

Research shows that when parents are actively involved in their children’s learning, kids will do better in school and will be more successful in life. But as every parent knows, raising a child is sometimes fraught with fear, moments of helplessness and occasionally downright panic. What are you supposed to do, for instance, when they fail a test, want their own credit card or start posting personal information on the Internet?

We spoke to teachers, administrators and psychology experts across the state who delivered the tips and guidance you need on topics from negotiating the school transfer system to applying for colleges—and yes, even having “the big talk” about dating and sex.

So as your child matures from “little Jimmy” into college-bound James, keep this step-by-step survival guide handy. Because you never know when you might find yourself facing a worst-case scenario. But don’t worry—if you do, we’ve got you covered.

{page break}

How to make peace with MySpace

AFTER WATCHING ONE episode of NBC Dateline’s “To Catch a Predator,” even a reasonable parent can succumb to full-on paranoia: The Internet, goes the investigative show’s underlying message, is a trolling ground for perverts—and your child could be the next victim. But unless you feel your child is in real danger (i.e., someone she doesn’t know is trying to arrange a meeting), installing Big Brother-style software, such as Net Nanny or WebWatcher, on the family’s computers can erode trust between parent and child, says Nancy Willard, executive director of the Eugene-based Center for Safe and Responsible Internet Use.

Such devices are also poor replacements for the guidance teens need on issues that inevitably arise when they chat and post profiles on social networking sites such as MySpace and Friendster. (According to a Pew Internet study, some 55 percent of online kids aged 12 to 17 use them.) An Internet monitor, for example, won’t explain to your teenage daughter why posting a picture of herself in a bikini on MySpace is inappropriate or what to do if someone asks her, “Are you a prude?”

No matter what situations your teen encounters online, freaking out about it is never a good idea. “If they do get into trouble, whether the problem is cyberbullying (in which kids harass others online) or sexual solicitation by a stranger, they will not come to you if they think you will overreact, blame them and ultimately take their Internet privileges away,” says Willard. And that’s the last thing you want. Here are some MySpace ground rules that Willard sets for her teens, modified from her book Cyber-Safe Kids, Cyber-Savvy Teens. —Jill Davis

1. Do not let your teenager use MySpace until you are ready to discuss what she should do if she encounters sexual imagery or sexual predators.

2. Before she joins MySpace, make your child understand that information posted is public and permanent—even if a website’s privacy controls are enabled. Posting personal information such as addresses, reputation-damaging material and private information about other people is never appropriate.

3. Tell your teen that you will check her MySpace page on occasion (it’s public, after all), but don’t take the tone of an officer. Tell her that you’re interested in her online life just as you’re interested in her school life.

4. Employ “the friend rule.” Every friend your child accepts on MySpace should be a friend known to her or a friend of a friend. “That way, if there is a problem, you can track it down to an actual person,” Willard says.

5. Create your own MySpace profile and communicate with your child about soccer games and scheduling through e-mail. Get other parents to join, as well. Information sharing need not be the purview of your progeny alone.

{page break}

Kindergarten: Timing it right

TODAY, 62 PERCENT of children in the United States attend full-day kindergarten (versus half-day), but 28 years ago, that number was closer to 25 percent. While research shows that kids in full-day programs often outperform their half-day counterparts in reading and math, Oregon is one of the few states that does not fund a full-day option. Still, 45 out of the state’s 198 school districts offer the longer day—though sometimes parents must fork over a portion of the cost. Susan Castillo, superintendent of the Oregon Department of Education, hopes to change that with her “Ready for School” initiative, which would fund full-day K in every district by 2011. To find out which schools currently offer a full-day option, turn to our Progress Report (p. 93), and to figure out whether full- or half-day school is right for your kindergartner, heed the following advice from ODE’s chief policy officer, Patrick Burk. —Sally Powers

FULL-DAY K VS. HALF-DAY K

“Additional time is not about longer naps and snacks,” says Burk. A full day allows teachers to delve deeper into academics. David Douglas School District released a report last year that found full-day students—regardless of ethnicity, income level or English proficiency—outperformed half-day kids in every subject on state assessments through the first grade.

“Many parents consider having a half day with their child to be a real gift,” Burk points out. “It’s a key part of children’s development, because parents are the most important teachers in their lives.” But parents need to use that time working on developmental needs, he advises, like reading to their child or taking him or her to the zoo to learn about the natural world.

{page break}

How to navigate the transfer system

WHEN YOU FIRST spied that adorable Victorian with the garden in the back and storybook front porch, you instantly fell in love. The only problem? Your dream home was outside the boundaries of the school you wanted your child to attend. But since Portland Public Schools has a transfer option, you figured you could make it work, and you can: After all, about a third of all PPS students don’t attend their neighborhood school. Still, you have to know how to navigate the somewhat complicated, multitiered system. Enter Judy Brennan, program director for PPS’s enrollment and transfer center (www.enrollment.pps.k12.or.us). She gave us the tips you’ll need to cruise through the process worry-free. —Kasey Cordell

STUDY UP. On Feb 2 at the Expo Center, PPS hosts Celebrate, where parents can meet with representatives from every school in the district. Stop by your local school’s booth even if you’re hoping to send your child elsewhere, because it doesn’t always work out: Last year, 22 percent of applicants stayed put.

TURN IN YOUR HOMEWORK ON TIME. PPS accepts applications for high school transfers from Jan 25 through Feb 22, and K-8 from Feb 2 until Mar 7. Don’t worry about submitting your application on the last day; it has no bearing on your child’s chances for getting into the school of his choice.

TAKE A FIELD TRIP. Some schools, like Sunnyside Environmental (K-8), require parents to attend mandatory meetings about the curriculum in order for a child’s transfer application to be considered. Check with PPS to find out if your school of choice is one of them—because if you miss these, you’ll miss out.

PPS accepts transfers based on a priority system. Here’s how the district decides who gets in:

First: Students transferring from Title 1 schools that did not meet the federal academic standards of No Child Left Behind for three years in a row.

Second: Students who come from a school that has been reconfigured into smaller school (such as those at Marshall High).

Third: Students from schools with special circumstances: Those at a certain elementary may have priority to alleviate overcrowding at a middle or high school.

Fourth: Students with a sibling already attending the school they want to transfer into.

Fifth: Those living inside the district are prioritized over those living outside of it. If there are still more applicants than slots, names are randomly selected.

{page break}

How to raise a millionaire

MANY OF US grew up in households where it was taboo to talk about money—or at least considered impolite. But according to Ted Scheinman, center director for the Oregon Council on Economic Education (www.oreconcouncil.org), a nonprofit that trains educators how to teach finances in the classroom, it’s one of the greatest disservices we can do to our children. Today the nation’s roughly 33 million teens spend $176 billion a year on items like clothes and video games. But according to the DC-based Jumpstart Coalition for Financial Literacy, only about 10 percent of high schoolers report learning about managing money in school. Although seven states require high school students to take a personal finance course before graduating, Oregon is not one of them. And thus the task falls to parents. Kari McClellan, co-founder of Financial Beginnings (www.financialbeginnings.org), a Portland nonprofit that teaches financial literacy in area schools, offers these guidelines for teaching kids to appreciate the power of money. —Sally Powers

ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

HAND OVER THE DOUGH

Allow your child to handle and exchange money. In a world of debit cards and online banking, money is an abstract concept to children.

Put her on the family payroll. Start with a $1-a-week allowance. If she wants to buy a toy at the store, explain to her how many of her dollars it will cost.

Involve her in real family discussions about money. Let her see what a bag of groceries costs at the store and then sit down with you as you balance your checkbook afterward.

MIDDLE SCHOOL

BANK ON IT

Open a savings account for your child. It’s time she understands banking in the real world. Bring her to the bank and encourage her to ask the banker questions like, “What’s a percentage rate?”

Teach bargain shopping. Give her a total sum, such as $25 a week, for her grooming products and entertainment, so she can begin to buy wisely.

Don’t criticize her for mistakes, or she may fear making decisions. For example, if she chooses a lower-priced shirt of poor quality, and the shirt fades after one wash, you’ll have the opportunity to speak to her about value. And if she overspends, work out a loan that she can take out from you.

HIGH SCHOOL

ESTABLISH CREDIT

Allow your 15-year-old to handle most of her own expenses (beyond food, shelter and essential clothing), based on a monthly number you work out.

Encourage her to get a part-time job. Paychecks provide the opportunity to explain to her taxes and long-term savings, and she’ll have a stake in her own budgeting.

Get her plastic. Scary? Sure, but on average, universities lose more students to credit card debt than academic failure. And even upon graduating, the average student has racked up $2,000 in credit card debt. Giving her a card early provides you with the opportunity to teach her how to use it responsibly.

Teach her how to read a credit card contract. McClellan points out that college students are one of the most likely groups to be victims of predatory lending, such as those offered by payday lenders and credit card companies. Explain to her how interest rates work and the importance of making more than the minimum payment.

{page break}

How to handle your moody adolescent

IF YOU’VE EVER perused the funny pages, you may have noticed Zits, the comic detailing the angst-ridden life of 15-year-old Jeremy Duncan and his bumbling parents. Depending on your kid’s age, Zits may seem less like a cartoon and more like your nightmarish reality. Jeff Sprague, a professor at the University of Oregon’s Institute on Violence and Destructive Behavior, says that with the onset of puberty, which can be as early as age 10, an influx of stress and sex hormones begins to inhibit the calming effects of the hormone serotonin. The result? Kids may act grumpy or aggressive for no apparent reason. Furthermore, those hormonal imbalances tend to make them less receptive to punishment and praise, because the part of their brains that associates consequences with behaviors is out of tune. Sprague offers these tips for cultivating a new attitude. —Brian Barker

1. Dish out discipline in small doses.

Sprague suggests that frequent, mild punishments are much more powerful than hefty ones. Try taking Halo 3 or a similar privilege away for an hour each night as opposed to nixing the game for a whole week. By doing so, you’re reminding your child that a particular rule violation results in a specific consequence.

2. Stay connected.

He’d probably rather mow the lawn than sit down for a bonding session with Mom and Dad, but it’s crucial to spend at least five minutes every day talking with your child. Sprague suggests asking the following: What went well today? Were there any problems? This gives you key opportunities to praise him for good behavior and to help him rethink things he could have handled better. It might sound simple, but it can go a long way toward preventing unhealthy antisocial behavior—even if he already seems like he’s from another planet.

When it’s more than a mood

IN OREGON, some 25 percent of girls and 12 percent of boys experience at least one major depressive episode between the ages of 12 and 17, but how do you know if your child is just experiencing run-of-the-mill adolescent turmoil or if there might be a real mental health issue? Drew McWilliams, the director of disorder services at Morrison Child and Family Services, says that if your child’s behavior or mood raises even a small worry flag, you should talk to a school counselor. “But remember,” he adds, “while some counselors may have a mental health background, most are going to refer you and your child to a professional outside the school.” Depending on your child’s insurance situation, there could be hundreds of options. If you feel comfortable exploring those with a school counselor, you should. But while the Portland School Board recently approved more than $2 million for school counseling positions that have been left unfilled for over a decade, there are plenty of schools that still lack counselors. If your school is one of them and you’re setting out on your own to find your child the help he needs, these agencies can help. —Camas Davis

{page break}

How to have "The Big Talk"

IF YOU’RE ONE of those people who turns red in the face just reading the word “testicle,” then you may be tempted to leave your child’s sexual education to the school system. That, however, would be a bad idea. A survey conducted by the National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy (NCPTP) reports that some 45 percent of kids aged 12 to 19 said that their parents are the No. 1 influence on their sexual decisions, while 31 percent said their friends are. Only 6 percent named their teachers and educators. In other words, teens want you to help them define their values and boundaries, even if you stutter while trying to wax eloquent about the miracles of baby-making and even if your teen looks at you like you’re an embarrassment to humanity (and he will). —Jill Davis

Half of parents of sexually active eighth graders are unaware that their kids are having sex.

Another reason not to rely solely on the schools is that the in-class curriculum can be spotty: Although Portland Public Schools does incorporate age-appropriate sexuality information into its health curriculum beginning in the fifth grade—covering topics from menstruation to HIV to safe dating—there are inequities across the district in the quality of the sexuality education kids receive, thanks partly to the district’s infamous funding problems. In some schools, kids may not receive sexuality education at all.

The reality is that, though your child may get medically accurate information in school, his attitudes and behaviors will primarily be shaped by you or, if you stay mum on the topic, by his teenaged pals. So how do you have The Big Talk? First of all, it is no longer de rigueur to have a Big Talk at all. Instead, have numerous small ones beginning when your kids are elementary-aged. These tips will help you work up your courage.

- “Bring the topic up casually and often,” says Lisa Cline, an education specialist for Planned Parenthood of the Columbia/Willamette. Use what the popular psych parlance of the day terms “teaching moments.” If your teen has gone gaga for MTV’s The Real World, ask her what she thinks about the contestants’ riskier behaviors.

- Talk to your sons, too. According to one NCPTP study, six out of ten teens think that the old double standard that asks girls to abstain, while boys get the wink and the nod, is alive and well.

- Don’t be afraid to say, “I don’t know.” If your child asks questions you can’t answer, look them up online together (www.teenpregnancy.org).

-

Teaching both abstinence and safe sex does not send mixed messages. Eight out of ten teens view discussing both as sending a “clear and specific” message, according to NCPTP.

h2. How to deal with a risk-taker

SOMETIMES TEENS TAKE such downright harmful risks that it seems there’s something seriously wrong with their heads. In fact, something is—sort of. In recent years, a spate of neurological research has found that the prefrontal cortex—that region of the brain that governs sound judgment and is key to impulse control*212;doesn’t finish maturing until a person’s 20s.

“This is the executive part of the brain,” says Amy Ruona-Banister, Portland Public Schools’ parent education coordinator. “Because it’s underdeveloped, teens are inclined to use emotion rather than logic to make quick decisions.” Which also explains why many teens are prone to experimenting with drugs. (The 2007 Oregon Healthy Teens Survey found that 39 percent of 11th graders reported having used marijuana.)

However, if you help to stimulate their brains in positive ways, they won’t be as apt to try dangerous feats for a quick rush. “The real goal is to get them out of their comfort zone,” says Ruona-Banister, whose team also leads parent-education workshops in area schools. These ideas will give your teens the buzz they’re looking for.

{page break}

h2. How to swallow your pride (and help your kid)

THERE YOU ARE at a parent-teacher conference, sitting confidently atop your third grader’s plastic school chair, waiting to hear the teacher say what a genius she is at math and what a pure joy it is to have her in the classroom. So you’re shocked when instead he delivers a bombshell: “Suzy’s math scores have plummeted, and last week she put earthworms in my desk.”

Karen O’Brien, a school psychologist and member of the Oregon School Psychologists Association, says that with only 20 minutes to discuss these issues with a teacher, there’s not a lot of time to let it all sink in. So it’s vital that you’re as positive as possible. The National Parent Teacher Association outlines the following steps for a smooth conference, and O’Brien shares tips for taking it all in stride. —Sally Powers

1. Don’t take the news personally. O’Brien warns against two common mistakes parents make: denying there is an issue and being overly defensive. Remember that the teacher is delivering this news so that the two of you can team up to help your child do better. Likewise, there’s no need to be overly apologetic—this is about the student and not an attack on your parenting skills.

2. Listen up and ask questions. Hear everything the teacher has to say first. Then ask specific questions about how long the problem has been observed, how often it occurs and when it happens. If it’s an academic issue, you should ask the teacher to compare examples of your child’s work against classmates’ so that you have a reference point. O’Brien notes that it’s also crucial to disclose anything going on at home—from a divorce to a recent move. This is information that will help the teacher understand what’s going on inside your child’s head.

3. Set an “action plan.” This will outline how you and the teacher will work together to help your child improve. It may be as simple as creating a memory device so your child remembers to turn in her math homework, but it can be as involved as bringing in counselors, tutors, etc. If you run out of time with the teacher, set up another appointment to decide what that plan will be.

4. Talk to your child. Don’t wait to go over what you and the teacher discussed—that can cause your child more anxiety. So begin with the positives: “Children need to hear what they’re doing well and that you’re proud of them,” says O’Brien. Then outline the action plan so that the child is clear on what is expected. Use language like “we” so children know that you and the teacher are a united front. And make sure to follow up with the teacher on how the action plan is or isn’t working.

{page break}

h2. How to school a prodigy

AS PROUD AS you may be to learn that your child is one of the 11 percent deemed gifted by Portland Public Schools, it is not a pass for you to put your child’s education on autopilot. “Being talented and gifted isn’t sufficient for success,” says Jeffrey Sosne, a psychologist with Portland-based mental health clinic The Children’s Program. In fact, gifted children who aren’t sufficiently challenged actually may end up falling behind their peers at school, so finding out the apple of your eye is a pint-sized whiz comes with unique responsibilities. To help your brainiac reach his full potential, consider the following.

IN THE CLASSROOM: At Portland Public Schools, students who score at or above the 97th percentile on a national test (such as the Iowa Test of Basic Skills) and who have been evaluated on other performance and behavioral criteria have the option of being identified as “talented and gifted” (TAG). Educators are required by state law to teach to these students’ elevated abilities. Andrea Morgan of the Oregon Department of Education recommends that parents first talk to the child’s classroom teacher about what strategies he’ll use to instruct your child, such as flexible grouping (in which the class may work on sixth-grade math while a TAG kid works on seventh-grade math). Contact the district’s Office of Talented and Gifted (www.tag.pps.k12.or.us) to find out about more in-class options.

OUT IN THE WORLD: Your child may have the brainpower to ace his tests, but Sosne says that “you need to have activities to instill a child’s passion.” That means parents may need to seek other resources in the community to ensure their child is being properly challenged and motivated. Enrolling your kids in programs like Saturday Academy (www.saturdayacademy.org) and OMSI Science Camps (www.omsi.edu) can often help meet the demands of a gifted child. (Both offer scholarships.) —Brian Barker

h2. How to ease your test anxiety

WHEN PRESIDENT BUSH signed the No Child Left Behind Act into law in 2002, student test scores became the primary evaluation tool for gauging the performance of schools—prompting a nationwide testing craze. But just how important and accurate are test scores in determining your child’s real abilities? Wilsonville-based W. James Popham, author of Testing! Testing!: What Every Parent Should Know about School Tests, sets the record straight when he says, “Tests just aren’t as accurate as you think.” Here’s why. —Sally Powers

CLASSROOM TESTS: Most teachers aren’t required to take a preparatory course on test construction, so the subject tests your child takes in school will vary greatly in quality.

STANDARDIZED TESTS: “They’re far better, but parents should not bow down to the ‘experts,’” Popham says, noting that every test carries with it a certain margin of error. And even reputable firms sometimes fail to be as spot-on as they’d like.

ACT & SAT: “Research suggests that aptitude tests are far less predictive of a student’s ability than people think,” says Popham. A better predictor are things like study habits.

The bottom line? Don’t ascribe too much significance to any one test. Just because your child brings home a single low score, that doesn’t mean he’s destined for mediocrity. “The big message is that effort is a far greater measure of success in life and college than tests [are],” Popham says.

{page break}

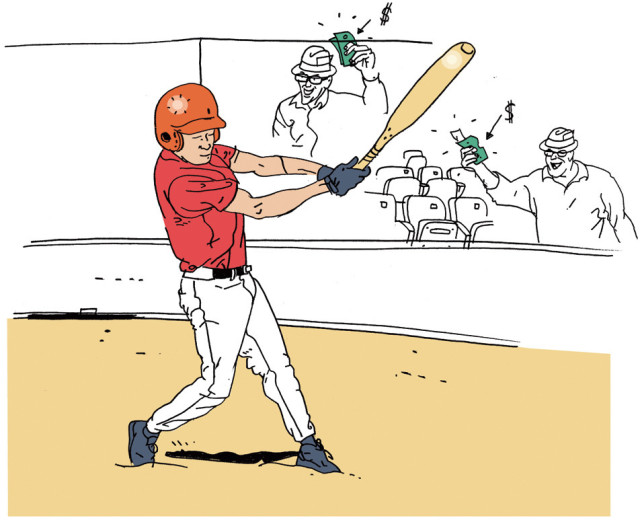

h2. How to turn athletic talent into cold, hard cash

JOHNNY JUST DUMPED the school carnival clown in the dunk tank for the 10th straight time, and you’re convinced he’s a future starting pitcher for the Oregon State Beavers. Given that the average in-state tuition at a public university has jumped to $5,836 a year, it’s hard not to get excited about the prospect of a free ride courtesy of a blistering fastball. However, securing a college sports scholarship takes more than natural talent: It requires patience, paperwork and, ironically, some financial investment. We talked to coaches, athletic directors and even sports agents to get the dirt on how to give your kid the best shot at scoring big. —Kasey Cordell

h3. 1. WARM UP

Get them involved in club sports, suggests Mike Hughes, the athletic director at Beaverton’s Jesuit High School, which last year sent 18 graduates to Division I programs on full or partial scholarships. Unlike standard school teams, club sports attract the best athletes in a given region and offer kids the chance to travel and compete at ages as young as 11. Plus, a club season gives your all-star additional months to improve his skills. And once your child hits high school, club tournaments are where the college coaches flock to scout. “College coaches typically don’t go to a high school to see one athlete,” says Hughes, who’s also the parent of a Division I volleyball player. “They go to club tournaments, where they can watch 10,000.” Note that this exposure may not come cheap: Fees at one of the metro area’s premier club volleyball programs, Nike Northwest Juniors, creep close to $3,000 per year, per athlete for the elite 18-and-under division.

h3. 2. PLAY THE GAME

Johnny’s junior year is the time to send an introductory letter, a stats sheet and even video footage to coaches at the colleges he wants to attend. Pay attention to the rules set out by the National Collegiate Athletic Association about how to protect his amateur status, like not taking prize money at competitions (visit www.ncaa.org for details). Agencies like Global Sports & Entertainment can also build and distribute his packet, but be prepared to shell out up to $6,000.

h3. 3. PICK A WINNER

The NCAA offers a list of helpful questions for him to ask during campus visits, like “What other players are competing for my position?” and “How would you describe your coaching style?” But the most important question is the one he’ll have to ask himself: “Is this the right school for me?” Because if he blows out his knee during his freshman year, you still want him to thrive academically—which is, after all, the point of college.

{page break}

h2. Secrets of college admissions gurus

OF COURSE YOU know how fantastic your child is, but colleges will only see and judge her by what she presents on paper. So we interviewed the admission gurus at a state school; a small, private liberal arts college; and one of the most storied Ivies back East to give us the scoop on what they’re really looking for. Grades, it turns out, will only get your kid so far. —Maura Flaherty

h3. THE IN-STATE SCHOOL

UNIVERSITY OF OREGON

$6,174/YEAR

If your kid wants to be among this Eugene-based university’s 4,748 freshman (65 percent of whom come from within the state), interim director of admissions Brian Henley says she’ll need to have at least a 3.25 GPA and 16 college-prep classes under her belt for automatic admission (see p. 94 to learn about AP and IB courses). If her grades don’t hit the benchmark, don’t despair: The admissions staff will also consider standardized test scores (SAT scores above 1103 beat the average here) and extracurricular activities. A must-do before sending in the application? Proofread it. Henley says he has to laugh when essays tout, “I would love to be a student at the University of Colorado-Boulder!” from applicants who have cut and pasted a generic mission statement into the application body.

h3. THE LIBERAL ARTS COLLEGE

UNIVERSITY OF PUGET SOUND

$31,700/YEAR

About 675 freshmen with an average GPA of 3.6 enter this small, private college in Tacoma, Wash., each fall to pursue a liberal arts curriculum that “encourages critical thinking, discussion and writing.” Assistant director of admissions Carolyn Johnson says that grades are looked at contextually here. If your child doesn’t have A’s, he should emphasize that he chose to take challenging classes. As for the essay, Johnson warns against making the admissions staff groan with another clichéd version of “My Mission Trip to Mexico.” Instead, help your child brainstorm an essay topic that he can make original. And encourage him to be communicative during his required interview—admissions officers want to know if the reason his GPA dropped one semester was due to a bout with mono.

h3. THE IVY LEAGUE COLLEGE

HARVARD UNIVERSITY

$31,456/YEAR

A paltry 9 percent of the roughly 23,000 annual applicants are invited to enroll at this elite institution. Though director of admissions Marlyn McGrath says there is no GPA minimum and no magic way to get accepted, it’s true that perfect SAT scores are not uncommon here and that children of alums get a second glance. However, if your family bloodline isn’t quite that crimson, make sure your child has taken a rigorous four years of the same foreign language (as opposed to the standard two). And while you’ve heard the term “well-rounded,” Harvard notes that they love “well-lopsided” students. So if your child’s obsession with the violin has taken him to the concert halls of Europe for international music competitions, it might also take him to Cambridge, Mass.

h2. SPECIAL ED: What to know

IF AT SOME point in your parental career one of your children is tested for a disability that could affect her learning (you would have consented to the testing ahead of time), you’ll be asked to attend what is called an Individualized Education Program (IEP) meeting—regardless of the outcome of the test. You may find out during this conference that your child does not require special education, but if she does, the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act requires schools to create an IEP that dictates accommodations the child will need (such as longer time to take tests) in order to level the playing field. “Many parents find the process confusing and intimidating,” says Janice Richards, the executive director of the Oregon Parent Training and Information Center, a Salem-based nonprofit that offers free assistance to parents of children with disabilities across the state. If you’re scheduled to attend an IEP meeting, Richards offers the following advice. —Brian Barker

DON’T GO ALONE. Finding out your child has a disability can be heartbreaking, says Richards, so it’s easy to understand why parents can be distracted during an IEP meeting. Meetings can also pack in more than a dozen participants, including your child’s teacher, school psychologists, special education teachers and behavior therapists. Fortunately, the Oregon Parent Training and Information Center will provide, at no charge, a trained advocate to counsel you beforehand and attend the meeting with you, and even take notes so that you can focus on the discussion (888-891-6784; www.orpti.org).

EDUCATE YOURSELF. You are your child’s No. 1 advocate, and to be effective, you must connect with resources. Talk to other parents, and openly communicate with your child’s teacher. And without fail, you need to understand the federal laws that protect your child. According to Richards, if you read just one thing about the laws, this 36-page special-education bible had better be it: the Oregon Department of Education Procedural Safeguards Notice (handed out at IEP meetings and available online at www.ode.state.or.us).