The Underdog

Image: Angela Cash

History, so the saying goes, is typically written by the winners, and in no arena is that more true than in the race between two candidates. Possessed of outsized ambition, the person who emerges victorious is, more often than not, the one with fat coffers, a well-honed message and a high degree of political savoir faire. This is not that kind of story.

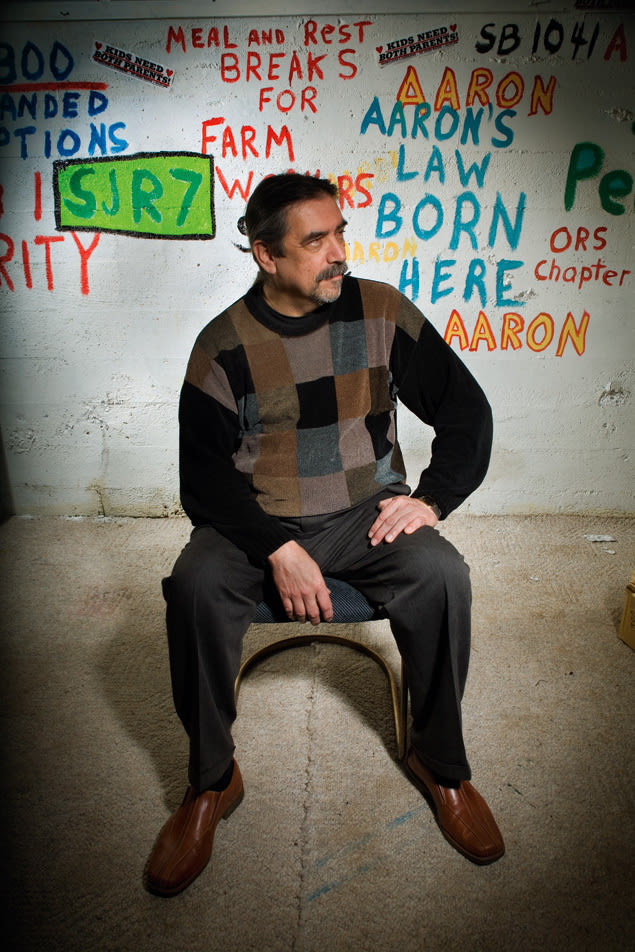

Instead, this is the story of an underdog, a long shot, someone who, by most predictors, is going to lose his race. A Portland man who dreams not of Washington, D.C., but of a modest office in Salem, his name upon the door: State Senator Sean Cruz, District 23.

Should Cruz, 59, beat the considerable odds stacked against him, he will pull in barely $20,000 per year, the current salary of an Oregon state senator. A meager wage, perhaps—but a small fortune to someone who once lived in a two-door Datsun B210, and who, until three years ago, was unable to afford health insurance. Cruz is the sort of candidate who will tell you, straight up, that he takes Zoloft for depression and is a proud member of the National Alliance on Mental Illness. Press him, and he’ll admit that, yes, his late son, who died while enlisted in the Army National Guard, was addicted to OxyContin and heroin. Cruz, fledgling politician, is a man whose handlers—if he had them, which he does not—would be rushing the stage to shut him up.

Yet this is only one way to spin the narrative of his life, for in 2002, after nearly six years of homelessness, Cruz became chief of staff for District 23 State Senator Avel Gordly, whose constituents live in Northeast and Southeast Portland. As chief of staff, Cruz has managed Gordly’s schedule, written drafts and revisions of bills and, increasingly, made policy recommendations. When Gordly heads to the senate floor, Cruz is usually beside her, watching debates unfold among legislators. Gordly has been so impressed with Cruz in his capacity as advisor that when she announced her intention to retire at the end of her term in January 2009, she encouraged him to run.

Cruz, a first-generation Mexican-American, now owns a home in District 23’s Parkrose neighborhood, a fact that also lends his story a certain pulled-himself-up-by-the-bootstraps appeal. That he’s experienced firsthand the issues that plague the district—racism, economic disparity, a lack of health insurance—makes him, he feels, uniquely qualified for the seat. On his blog, BlogoliticalSean.blogspot.com, he writes that he is not a “career politician” but a citizen, one whose story reflects “the issues Oregonians care most deeply about,” and not the issues “of those who are efficient campaigners.”

Image: Angela Cash

This last statement is a subtle dig at his opponent, four-term state representative Jackie Dingfelder, a 47-year-old environmental planner who political pundits say will be nearly impossible to beat. Not only is she chair of the House Energy and Environment Committee—a powerful post that she’d give up to become a freshman state senator—but the list of 100-plus people and groups that have endorsed her campaign, from City Commissioner Sam Adams to Attorney General Hardy Myers to the American Federation of Teachers, reads like a who’s who of Portland political insiders.

Still, Cruz has what Dingfelder does not: a story, one that he hopes will resonate with constituents, several dozen of whom showed up in January for his fundraising kickoff at Greg’s Backyard Grill & Bar, a family-style restaurant on SE 82nd Ave. Standing beneath a TV screen flashing Keno numbers, Cruz—his face resembling a weather-beaten Gregory Peck’s—divulges the details of his life. How he came from little and wound up with less. How in 1988 he lived with his wife and four kids in a tent in his in-laws’ backyard in Battleground, Washington, and had to work a temporary job as a rigger at Portland’s Northwest Marine Ironworks, “something I didn’t know a damn thing about but took anyway, because it paid 13 dollars an hour.”

That was before things really went into the crapper.

Cruz no longer has a wife, nor contact with his three surviving children. In mid-January, four months before the Democratic primary in which he’ll face Dingfelder, he also lacks a campaign manager, a war chest and any more endorsements than can be counted on one hand. Yet, if any of this bothers him, if he notices the people leaving empty “Support Sean Cruz” envelopes alongside their empty beer bottles after he concludes his 35-minute speech, he doesn’t show it.

Cruz looks elated, if a little like a man who, having waded into a swift-moving river, realizes he’s in for a very hard swim. “Going from homelessness to a Senate seat in six years—yeah, that’s a great story,” he says.

It would seem axiomatic that each district votes into office the contender it feels best represents the interests of the community. But District 23 is not one community; it’s dozens, combining Northeast Portland’s House District 45 (where Dingfelder has been representative since 2001) with Southeast’s House District 46. Bordered by NE Marine Dr to the north, NE 143rd Ave to the east, NE 21st Ave to the west and SE Knight Dr to the south, it claims (like all state senate districts) roughly 114,000 constituents. Unlike more homogenous state senate districts, however, the constituents of District 23 live in neighborhoods as disparate as verdant Mount Tabor and less-than-verdant Lents; upscale Laurelhurst and struggling Concordia.

Local governance must give equal attention to the business needs of environmentally friendly pet-food stores in Beaumont-Alameda and discount mattress warehouses in Foster-Powell. They must heed the concerns of those who own million-dollar homes around Grant Park and those who live in trailer parks on NE Killingsworth St. This part of the city also happens to be home to large populations of recent immigrants, many from Mexico, Somalia, Vietnam and China, nearly all of whom must navigate a new language and culture to find jobs, housing and schools for their kids. While similar “in-migration” trends are occurring in other parts of Oregon, they are taking place more rapidly in District 23, which makes the area both tremendously fertile and tremendously challenging to govern.

Since 1996, the district has been represented by Avel Gordly, who two years ago, disgusted with what she considered extreme partisan politics in the Oregon legislature, left the Democratic Party and became an Independent. The first African-American woman senator in Oregon’s history, Gordly is known for speaking her mind while being, in the words of Peter Wong, political reporter for Salem’s Statesman Journal, “a voice for procedural fairness and for the rights of minorities.” Her accomplishments include winning support for Measure 14, which removed all racist language from the Oregon Constitution; petitioning successfully to increase Oregon’s minimum wage; and pushing through the Expanded Options bill, which requires school districts to offer college-credit classes to high school juniors and seniors (and pay for them) in the hopes of getting more underserved kids on the college track.

The economic divisions within District 23, evident during Gordly’s tenure—a 2000 census shows the median family income in Alameda-Irvington to be $84,347, and in Parkrose, $34,092—are only widening. According to Gordly, between the time that the Oregon Health Plan Standard began to purge its rosters in 1995 and the time it closed enrollment in 2004, some 43,000 people in District 23 lost their health insurance—more than in any other district in the state. Gentrification, she says, continues to price some residents, notably African-Americans, out of the area. In other words, District 23 is a kind of microcosm for Portland’s most intractable problems.

These are among the issues facing whomever is elected in November, a race that—with 54 percent of the district registered as Democrats (and as yet no Republican contenders)—will in all probability be decided two months from now, in the May primary. It would seem a tough first gig for any politician, let alone an untested one like Cruz, but Gordly, who for five years has watched Cruz grow into his role in Salem, thinks he is ready. “He has a heart for public service,” she says.

Image: Angela Cash

Gordly initially met Cruz in the late 1990s, when he was volunteering for organizations like the Oregon chapter of Weed and Seed, which works to reduce drug abuse and gang activity in urban neighborhoods. “His worldview was very much in sync with mine,” she says, so much so that in 2003 she asked him to become her chief of staff. Gordly wanted someone who understood how the district’s rapid growth was affecting people’s lives, and Cruz’s experiences helped remind her every day who among her constituents needed her most. “We never, ever, ever want to forget,” she says, “that the people we serve are also the people at the bottom.”

Cruz, in Gordly’s mind, is the kind of person whom not only the district needs, but whom the Oregon Senate needs: “The person who is willing to question conventional wisdom. The person who’s not going to just march to the drummer, meaning the party mantra.”

Someone, in other words, a lot like herself.

It’s noon on Sunday, and Cruz is the only customer in Tupelo Joe’s, the barbecue joint and blues club on NE 107th Ave & Sandy that he refers to as his “semiofficial campaign headquarters.” After warmly shaking my hand, the six-foot Cruz, for no apparent reason, breaks into a rippling laugh. “I am the only candidate who drives a hand-painted car!” he says of the royal blue 1994 Nissan Sentra parked across the street. “I Indianized it!”

With his dark ponytail and Western shirt, Cruz could easily pass for Native American, though his father was Mexican and his mother was Irish. Mostly ignoring a plate of rib tips, he spends the afternoon going over his past: Born in 1948, he grew up in Fairfield, California, the son of a farm-worker father who became a deputy sheriff, until a car accident ended his father’s career. His mother was a legal secretary. Until his late 20s, when he finally decided to get serious about his education, Cruz lived the life of a “starving musician—I mean starving.” He graduated from Sonoma State University with a degree in political science and aspired to become a political writer.

Those dreams were deferred when Cruz met 21-year-old Gina Micheletti during her shift tending a bar in San Francisco. They were married, but soon after their first child was born—and after a short separation—his wife decided to rejoin the Mormon Church, the faith she’d grown up in. Religious differences (“I’ve never been one for dogma,” says Cruz) were a source of constant tension, as were the couple’s declining fortunes: A Bay Area start-up where Cruz found work as an editor went bust; ditto, a business he launched to develop software for the residential real estate industry. By 1988, now with four children, “we were totally broke,” says Cruz, which is how they ended up in a tent behind Gina’s parents’ house. His in-laws were less than impressed with Cruz’s potential. Work, again, was tenuous: After the rigging job, he lost a job with computer manufacturer Tandy, when it downsized. Whether due to the financial pressures or, to Cruz’s mind, his wife’s indoctrination by the church, or both, in 1991, he and Gina divorced, though a joint-custody agreement allowed Cruz to see his kids, he says, “an average of 180 days a year for five years.”

Image: Angela Cash,Angela Cash

The arrangement ended on February 12, 1996, when Cruz’s ex-wife left Oregon, taking the four children, then ages 7 to 17, with her. For three weeks, Cruz had no idea where they were, until a lawyer he hired finally located them in a Mormon community outside of Ogden, Utah. Cruz has never again had any substantial contact with his family—though he insists he’s tried. Over the years, the wound of the loss has festered into obsession: Nearly every story he tells begins and ends with his need to reconnect with his kids.

Following their disappearance, Cruz sank into depression and fell months behind on his rent. He took a job at El Hispanic News, but clashed with the publisher and was fired. He moved over to the Portland Observer, the city’s nearly four-decade-old African-American newspaper, where he helped launch a Hispanic section called El Observador de Portland. According to publisher Charles Washington, Cruz was a good editor and even headed up a special election edition in 1996—during which Cruz first learned about and endorsed Gordly—but the Observador didn’t generate enough revenue for the paper. Cruz was let go.

“I had lost all hope,” Cruz says. Late one night, at a New Year’s Eve party in a riverfront home near the Sellwood Bridge, he found himself staring at the water and contemplating suicide. “I was just thinking about walking out into the Willamette,” he says. Before he could, a woman came up beside him, put her hand on his shoulder and started to pray. “And I thought, ‘If I don’t go to a church,’” says Cruz, “‘I am going to die.’”

Cruz ended up at Victory Outreach on NE Alberta St, a nondenominational ministry that he had written about for the Observer several months earlier. Max Garza, Victory’s pastor, remembers Cruz looking “handsome and clean-cut” during that first newspaper interview. But when Cruz showed up at the church the next time, Garza says, “he was distraught, emotionally dysfunctional—I would say, almost suicidal.”

Victory Outreach typically helps people who’ve been incarcerated, addicted to drugs, or working as prostitutes. Though Cruz met none of these criteria, Garza made an exception.

“Pastor Max said, ‘Sean, I don’t know what your issues are, but if you need a place to stay, we’ve got a bunk bed for you,’” recalls Cruz. He wound up staying five years.

This is the narrative Cruz tells, in a somewhat shorter version, at the fund-raiser at Greg’s Backyard Grill. He talks, too, of his climb out of those depressive depths: volunteering with the Portland Police Bureau’s Crisis Response Team; getting his real estate license in 2000; starting to take antidepressants, thanks to the Oregon Health Plan Standard (from whose rolls he was later cut).

After his speech, during which he also touches briefly on his political platform—expanding health coverage, opening homes for the mentally ill and improving care for veterans—Cruz chats with a few of his constituents. Alice Andersen, owner of Bob & Alice’s Tavern on SE Foster Rd, tells him that she needs to work a second full-time job at an electronics plant in order to pay her bills. “The politicians care more about the spotted owl than they do about people and their livelihoods,” she says of candidates like Dingfelder. “I may never be able to retire–I’m 62 now, my God.” Adds John Feuerstein, the liquor-store owner who arranged the evening’s event, “Take a look at the district. You’d be hard-pressed to find any wetlands here. We’re more interested in our businesses.” When I ask George Kuppler, another liquor-store owner, why he supports Cruz, he says, “Sean has a depth of life experience; he wears his heart on his sleeve.”

If Cruz relies on heart and the power of his story, Dingfelder uses old-fashioned shoe leather, going door to door, as she has for seven years, to meet her constituents and listen to their concerns.

“I really do feel that I truly represent Northeast and now I’d like to represent central Southeast Portland,” says Dingfelder, a petite woman in a tidy Tyrolean jacket, who checks in several times with her twentysomething campaign manager during a one-hour Saturday morning coffee on NE Broadway. Dingfelder has an impressive résumé, from which she quotes liberally. “The Oregon League of Conservation Voters puts out a scorecard,” she says, of the organization on whose board she’s served. “I won Environmental Champion of the Year last year, and I’ve gotten 100 percent every time on my voting record.” She also sits on the board of Planned Parenthood and champions both electronic-waste recycling (House Bill 2626, passed in 2007) and salmon recovery (she’s worked for both the Tualatin River Watershed Council and For the Sake of the Salmon).

Dingfelder, who lives in the Rose City Park neighborhood with her husband, is a model Portland politician: She cycles to work—a point driven home by a campaign flyer photo of her on a mountain bike. She works to restore the Willamette River. Her wish list—tax reform, living-wage jobs, better access for all to health care—is unassailable.

These credentials certainly will resonate with some in the district, but when I tell Dingfelder about Alice Andersen’s assertion that lawmakers care more about wildlife than about people, she is quick to counter: “The environment is not a special interest; it’s a human interest. If we don’t have clean air and clean water, we can’t survive.”

Still, Dingfelder doesn’t necessarily need Anderson’s support to win. Of the 114,000 or so people in District 23, only about 20,000—maybe—will cast a ballot in the primary, according to Bill Lunch, an Oregon State University professor of political science and regular on-air political analyst for OPB. And the issues that Dingfelder champions are precisely the sort that resonate with many voters. People who vote “tend to have higher incomes, be better educated, and are going to tend to care about more abstract issues: the environment or women’s rights,” Lunch notes. “But if you ask a typical citizen what his or her number one concern is, the likely answer is economic problems.”

On the chances of Cruz’s hardscrabble story winning votes by appealing to people like himself—those who are struggling or below the poverty line—Lunch is less than optimistic. “These are not the people who typically show up at the polls,” he says. “To do what Cruz is doing requires getting attention—it’s a huge, if not insurmountable hurdle…. Cruz may have a powerful story, but even the most powerful story has to be communicated to people who aren’t really paying attention.”

It’s Friday afternoon, and Cruz has just returned from a day of work in the capital. Still in coat and tie, he programs his TiVo to record his favorite show, The McLaughlin Group, and then settles into a wicker chair in the living room.

“I think it’s just a matter of [me] being a better match for the district,” he says of his candidacy. “I’m no slouch on the environment, and I’m committed to bringing the salmon back, but geez, that is not the chief issue in the race.” He repeats his concerns about access to health care, illustrating the point with an account of how he nearly died of the flu in January 2005, a time during which he was uninsured.

Cruz’s habit of turning the personal into a public platform may be an asset to Gordly, but to others, it is his Achilles’ heel. “Sean’s doings in the last legislative session bugged me,” says Jack Bogdanski, a professor of law at Lewis & Clark Law School and the author of the acerbic Jack Bog’s Blog. “He got his car towed unjustly from a private lot, and that sent him into a tizzy that led to Avel’s crusade against predatory towing.”

To some, a more egregious example of Cruz allowing passion to dictate politics occurred after the 2005 death of his 23-year-old son, Aaron, an Army National Guardsman who also had a long history of drug addiction. After having a severe seizure, Aaron ended up in a Utah hospital in a coma and died five days later, his father by his side. Soon after Cruz returned to Oregon, he began railing vehemently against President Bush, the war in Iraq and the dismal state of veteran’s care, though none of these things played a clear role in Aaron’s death. He also drafted a state bill that makes the crime of parental abductions a civil liability, giving Cruz and parents like him the right to sue the abductor without having to press criminal charges. By recounting the story of his children’s disappearance back in 1996, he successfully pushed the bill through the Oregon legislature. Now called Aaron’s Law, Senate Bill 1041 was signed by Governor Kulongoski in 2005.

When I ask Cruz whether he is using politics as a means to fix publicly what he could not personally, and whether he thinks becoming a senator might be the thing that moves his surviving children to rekindle a relationship with him, Cruz says, “I don’t know. Right now, they can find me on my blog.”

Just before Christmas, Cruz posted a couple dozen pictures of his kids to his website under the heading “My Well-Loved Children.” In them, they are riding tricycles, trick-or-treating and playing at the beach. His youngest, 7 when he last saw her, turned 20 this year.

Cruz finally found himself a campaign manager, a goateed 25-year-old named David Linn, in early February. Around the same time, he began e-mailing regular dispatches of his plans should he be elected, efforts that seemed to indicate that his campaign was finally amping up. If he loses his race, Cruz says, he’ll finish his duties at the legislature until Gordly retires, “and then I will retire from it, too.”

It may not sound like the statement of a man gunning to win, but in the context of Cruz’s life, winning may not be the point. No matter the outcome on election day, even if he finds himself a senator, the happy ending to Sean Cruz’s story may remain unwritten, for what defines him has less to do with all that he’s accomplished than with what he knows is still missing.