Game On!

Image: Michael Novak

Three years ago, the Portland Trail Blazers seemed broken beyond repair. Since then, the team has been reinvented—reimagined, you might say—with some of the most youthful, talented, and flat-out lovable players in the NBA. Its potential is explosive—and entirely unpredictable. As these superheroes in sneakers power up for the new season, we take a close look at the five characters most likely to answer the call of “Rip City” and lead the Blazers to succeed in their ultimate mission: a world title.

Image: Michael Novak

Kevin Pritchard

GENERAL MANAGER

Façonnable dress shirt. Robust handshake. Sustained eye contact that’s as eerie as it is magnetic. Friendly, not-quite-patronizing speech littered with polished spin. A distinguished-looking sedan parked in the lot. By any measure and every detail, Kevin Pritchard is the epitome of upper management.

Under Pritchard’s three-year reign as the Trail Blazers’ general manager, the team has enjoyed the biggest turnaround in its 40-year history. In 2006, Portland was moribund, bouncing through the motions in front of an empty Rose Garden. Last year, the Blazers won 54 games, made the playoffs, and turned the Rose Garden into the hottest ticket in town. It’s an ideal business-school case study. Think about it: clean-cut executive takes control of much-beloved business, cleans house, preaches community values and outreach, handpicks talent throughout the organization, and creates opportunities for the team to succeed. Most impressively, though, Pritchard has lifted the spirits of a franchise that had become accustomed to losing and has helped rekindle the fans’ throaty chants of “Rip City.”

But Pritchard’s golden touch, and the leaguewide envy it’s generated, have also changed him. As the national media has tried to figure out how this Svengali works his magic, Pritchard has evolved from fresh and hungry to entrenched and guarded. The fiery former point guard who used to yell or wag a finger in disgust has now taken to out-of-body self-reflection.

When his right-hand man, Tom Penn, was offered a promotion by a rival organization, Pritchard greeted the potential departure wistfully: the attempted poaching was, he said, a reaffirmation of the Blazers’ new culture. To no one’s great surprise, Penn ended up staying put. After big-name free agent Hedo Turkoglu spurned Portland by signing with the Toronto Raptors, Pritchard offered only token disappointment (“We want players who want to be here,” he said), brushing off a $50 million offer and franchise-transforming move as if they were wayward insects. In August, he publicly announced Brandon Roy’s massive $80 million contract extension. But privately, Pritchard issued a challenge to his new superstar: “What is your destiny going to be?” Pritchard treated this moment, one of the most significant in his tenure, with existential examination.

Now comes the hard part: trusting his vision and hard work to pay off in the present. Pritchard’s fondness for poring over statistical analysis and his card shark’s gift for fleecing other owners out of talent have earned him the spotlight, but ultimately, the probabilities and random chance of the game will be his judge.

Image: Michael Novak

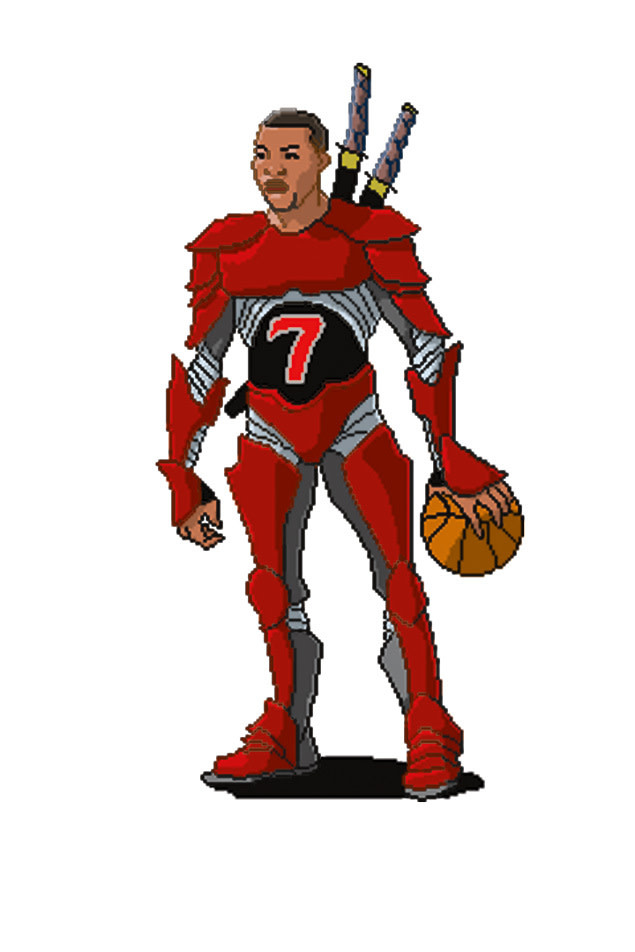

Brandon Roy

GUARD, TEAM CAPTAIN

Brandon Roy could be the poster child for Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink. Watching Roy, the athlete, play for a quarter; hearing Roy, the person, answer questions after a game; and observing Roy, the father, play with his two young children, is to know instantly and intimately that this gritty shooting guard is, as basketball scouts like to say, something special. Commentators call him an “old soul.” And his improvisational drives to the hoop have been compared to jazz.

His domination of an opponent might start with a slow-motion back-and-forth dribble, as he waits, waits, waits for the slightest shift in balance to exploit before exploding to the basket. An interview might begin with a chess master’s deconstruction of his own strengths and weaknesses. On the court and off, Roy’s talent puts him on a plane apart from his teammates. He knows this. When he first put up the hand-scrawled sticky-note reminder in his locker that read “Be humble,” it was a message meant solely for him. Now it’s a commandment for the entire Blazers team.

Staying grounded can’t be easy. In three seasons he’s been voted the Rookie of the Year and played in two All-Star games. Last season he earned a spot on the All-NBA Second Team. This year, Roy will likely be in the mix for the league’s Most Valuable Player.

Roy, the brand, is coming along nicely as well. The smiling assassin has appeared on the cover of Dime magazine and on the front of the NBA 10: The Inside video game. He sells sneakers for Nike in prime time, and with his freshly signed contract (five years, $80 million), he is the rare NBA creature to hold a prestigious “max contract”: the Blazers can’t legally pay him any more than that.

Naturally, great salaries beget great expectations, especially from the man cutting those checks, Paul Allen. The Microsoft co-founder and owner of pro football and soccer franchises is one of the world’s richest men, but so far he’s been unable to buy a championship. Putting his trust in Roy’s hands seems like the savviest of moves. Roy’s late-game calm recalls Jordan. His basketball intelligence earns him comparisons to Magic. His popularity in Portland rivals that of Clyde the Glide. But before this old soul can ascend to the realm of those legends, he must deliver the grail: an NBA championship.

Image: Michael Novak

Greg Oden

CENTER

When things go wrong for a cash-heavy man-child like Blazers center Greg Oden, everyone has a different explanation. Ask 10 people how the seven-foot-tall, 285-pound 2007 top draft pick can finally live up to expectations, and you’ll get 10 different answers. Play defense without fouling out. Figure out how to turn left with the ball. Hone a hook shot. Increase his vertical leap. Toughen up. Get mean. Improve his footwork. Set better picks. Get in shape. And, oh yeah … settle down and just Be. Greg. Oden.

That last bit of advice is the one you’ll most often hear coming from the Blazers. Publicly, the team brushes off Oden’s slow acclimation to the NBA, attributing it to his recovery from the microfracture knee surgery that grounded him for the entire 2007—08 season. But the real reasons lie about five feet higher. Professional athletes endure two rehabilitation processes after an injury: the physical and the mental. Oden’s body has healed. But his mind seems tethered to a dark cloud that, last year, followed him everywhere. He seemed sullen and adrift from his teammates. When cornered by microphones he offered thudding, monotone answers that recalled Eeyore.

So this summer Oden retreated from the scrutiny. He spent months in Columbus, Ohio, where he’d played his one year of college ball for Ohio State. There, he did low-key workouts with Blazers staffers, according to Portland strength and conditioning coach Bobby Medina. In August, while participating in a camp for Team USA Basketball, Oden admitted that he had been speaking with a sports psychologist, generating his only headlines of the summer. In the alpha-dog world of the NBA, where toughness is worn like armor, it was a startling confession. Oden was finally starting to open up.

That’s a positive sign. Last season, the Blazers were hands-off with the 21-year-old. Upon season’s end, the weather changed. Nate McMillan pointedly stated that he expected Oden to have a “big summer.” Kevin Pritchard, a former player himself, was more direct in challenging his big man: “I’ve been in locker rooms,” he told a reporter. “I’m not afraid to challenge guys.”

Even though Oden’s played only a hundred games, roughly, since graduating from high school, it’s fair to say this is his moment of truth. If he fails to become a backboard-shattering brute, the whispers of draft-day bust will increase in volume. But if he can Be. Greg. Oden? If he can fulfill the dreams of those who packed Pioneer Courthouse Square before he played a single game? A team with that guy in the middle could contend for a title. And soon. Which may be the only outcome that will silence his critics.

Image: Michael Novak

LaMarcus Aldridge

POWER FORWARD

To teammates, analysts, and fans alike, LaMarcus Aldridge is a conundrum. At 6-foot-11, he towers over almost everyone he comes in contact with, yet when conversing he has a tendency to look down. Not at the wee folks he’s talking to, but past them, all the way to the ground. To his feet. In the rare print-media profile—there have been only two—he comes off as shy and uncomfortable with the attention. In person, it’s clear that his lack of eye contact and his navel-gazing are less a nervous tic, and more of a self-defense mechanism for blocking any perceived judgment.

It makes sense. Since Aldridge entered the league after his sophomore year at the University of Texas, his unique game has drawn both gawkers and detractors. His tattooed arms, loping stride, and penchant for drifting away from the hoop instead of barreling toward it made him an easy target for those who believe that power forwards should be, first and foremost, powerful. Despite solidifying himself as the Blazers’ second most valuable player—behind Brandon Roy—a perceived lack of toughness dogged him every time a feathery fadeaway jumper missed its mark.

Until this past February, that is, when the ballet dancer began transforming into a bull. Where once Aldridge relied on his freakish athleticism and seven-foot, five-inch wingspan to avoid contact, he was now banging, inflicting psychological and physical damage on his opponents. The kid who used to dart gracefully through the lane for an open shot started charging and dunking violently on anyone who got in his way. And instead of shrinking in the face of on-court skirmishes, Aldridge now stoked the fire, gesticulating at opponents’ benches after big plays. Yet as he unleashed his inner beast, he lost none of his agility or refinement. He even became a coach-on-the-floor leader.

Aldridge is perhaps best understood as a benefactor—and propagator—of a leaguewide revolution that has swept the power forward position. He shoots 20-foot jumpers like a marksman. He possesses the foot speed to stay with much smaller guards, but also has sufficient bulk to do a passable defensive job against the league’s centers. He’s encouraged to be as active as possible in disrupting passing lanes and gathering rebounds. A similar player in the 1980s would have languished under the basket, tasked solely with bumping and bruising.

Of this new model of Swiss Army knife power forward, there isn’t a better example than Aldridge. General manager Kevin Pritchard is touting him as a future All-Star. His raw skill means his coach, Nate McMillan, draws up the first play of most games for him, hoping a hot start from Aldridge will crush the opposing players’ spirits. But those eyes remain humbly focused on the ground, his nose to the grind. While Blazers fans may never fully understand Aldridge, this season they will come to fully appreciate him.

Image: Michael Novak

Nate McMillan

COACH

Blazers head coach Nate McMillan patrols practice with his arms crossed and his face set blankly. His eyes pan from side to side, scanning for any trace of imperfection amid the sneaker squeaks and sweat of the on-court melee. He wears his shorts high on his waist, and his hair is precisely buzzed in military style. Everything about his appearance screams old school. Yet despite his predilection for rigidity, he knows that to succeed as a coach in the NBA—a horribly cutthroat milieu where players get the praise, upper management calls the shots, and the coach just gets fired—you have to remain flexible.

It’s a delicate dance. It means balancing strategy and tactics, emotional appeal and stone-cold discipline. One must stick to a core philosophy while constantly adapting to advances in game play. But above all, a coach has to be able to connect with and motivate players immersed in the ADD era of hip-hop and Twitter. Even at the age of 45, McMillan finds this balance through sheer authenticity. He’s been there and done that as a player, and he isn’t shy in the slightest about telling his young squad about it.

McMillan’s knowledge, and his unquenchable thirst for more of it, are his greatest weapons. He watches opponents’ game tapes endlessly, rewinding plays over and over in search of the slightest weakness. He’s been known to pull all-nighters in his office, mulling over prospects in the days before the NBA’s annual draft. He speaks fondly of four-hour dinners in China during the Olympics, arguing strategy with his fellow coaches on the US National Team. He spent the four-day All-Star break—his only extended respite between September and May—in a gym watching his son play basketball for Arizona State University. Asked how it went upon his return, McMillan began breaking down the play that decided the game.

If there’s been a knock on McMillan, it’s that maybe he’s too hard on a squad that is still one of the most baby-faced in the league. Some say he stifles the development of young players by being too unyielding, too unwilling to cede control to anyone who’s actually on the court. Only the sheer force of Brandon Roy’s All-Star talent forced McMillan to loosen his grip a tad last year. He turned late-game play-calling duties over to Roy, the team captain. Yet that trust never extended to the rest of the squad. McMillan—a key cog in the well-balanced Seattle SuperSonics teams of the mid-1990s—knows that a coach alone can’t win a championship. But will he be able to believe in his players enough to let them make the Blazers their own?

This September, when a group of fans toured the team’s practice facility, McMillan excitedly began shaking hands, not as a team marketeer, but as a fellow fan of the game. Many photos from that day found their way onto Facebook walls and web forums; McMillan’s grin was the widest of anyone’s.

It’s a relaxed side rarely seen in public. But if his maturing team continues to earn his respect—and if McMillan in turn loosens his hold on the reins long enough to let his players play their game—that smile could become a permanent fixture, perfect for a victory parade through the middle of Pioneer Courthouse Square.