Right Turn

Tuesday, 10 A.M. in the quiet lull following the geriatric early-bird stampede at Shari’s restaurant in Garden Home, a bouncy Mexican waitress is circling the hunched man at the counter like a gnat wearing an apron. Bzzzzzz. Coffee refill. Bzzzzzz. Water refill. Bzzzzzz. Ketchup. Chipper blasts of staccato Spanish choke the airspace behind her.

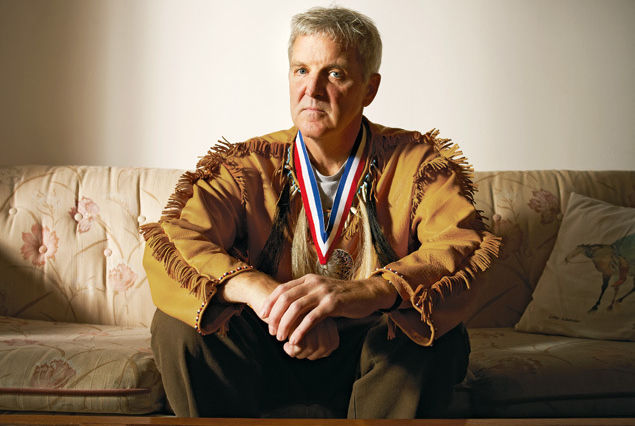

Sandwiched on his stool between the foreign chatter of the kitchen staff and a clearly disturbed man involved in a deep conversation with his scrambled eggs, 57-year-old ex-Marine William Krause leans heavily into the bar. He is a man apart. Not quite agitated. Not yet fed up. He’s just … tired. Tired of often feeling like the odd man out in the neighborhood he’s spent almost his entire life in.

As the banter from the waitress and the cooks swirls around him like vapor trails, Krause cements his elbow firmly between the syrup dispenser and a saucer of single-serve creamers and begins reeling off a calm, measured diatribe.

“I don’t think illegal aliens deserve health care,” he says, not exactly yelling, but also not bothering to lower his volume for the audience members, who may, themselves, be illegal aliens. “I don’t think they deserve to be here at all. They’re breaking the law. My adopted family were Jewish immigrants, and they had to go to Canada and then come here. They did it the right way.”

There is no white spittle of hate hanging off his rhetoric. Krause—white-haired, fit, and conversational—delivers his diatribe in an almost-sleepy drawl. As his story unspools over breakfast, it’s hard to argue that he hasn’t earned the right to his opinion. “I’m a patriot,” he says nonchalantly. He begins reciting a particularly valorous lineage. His father was killed fighting in Korea. His stepfather was stationed at Pearl Harbor during World War II, and his namesake uncle was a fighter pilot in that war. Krause himself served six years in the US Marines and another five as a machinist on a nuclear submarine. He also spent time as an explosives operator at the Army’s Umatilla Chemical Depot in Hermiston. When his service ended, he volunteered with the state police in the Columbia River Gorge, where he eventually discovered and named Metasequoia Creek. Then came a stint helping with disaster preparedness on the Portland Neighborhood Emergency Team, or NET. (Krause fears a devastating subduction earthquake is inevitable.) Six months ago, he signed up for yet another call of duty: membership in the Oregon State Defense Force, a volunteer squad that backs up the state’s National Guard during emergencies.

“I love my country,” he says. “And I love my state.”

But over the past few years, things have begun to unravel for Krause. A steelworker by trade, he was recently laid off from his job repairing pipe coating. State funding cuts put a stop to his work in the Gorge. He’s now only loosely involved with the NET team due to what he calls mismanagement. And then there is the perilous path he believes the country is on: A socialist in office. Defense being weakened overseas. An erosion of personal liberties. The country his father died for and that he himself has spent his adult life defending is slipping away.

So when a friend on one of Krause’s disaster-preparedness websites told him about a group called the Liberty Guard, a militia group based in Missouri, he signed on. A national “unorganized” (i.e., unofficial) militia, the Liberty Guard shares Krause’s distaste with the current shape of the nation. Plus, the group didn’t seem extreme in its views on race and religion, which was even more appealing to Krause. “There’s a lot of wackos out there, and I’ve dealt with some of them,” he says. “I told the LG I believed in a Creator and not one God, and they said they were cool with that.”

And unlike other groups Krause had been in contact with over the years, the Liberty Guard was doing more than just talking. It had a constitution. A liberty proclamation. A flag. It offered military training. More importantly, unlike militias that tend to clump together regionally, the guard’s membership stretches across the country.

“We believe in the Bill of Rights so much that we are forming defensive forces for secession, if that is what it takes,” says a Liberty Guard spokesman, who wishes to remain anonymous. “We see that we are living in the downfall of the current Republic.”

As the columns of freedom collapse around it, the Liberty Guard has taken the hard-line position to “defend ourselves to the last man, woman, and child.” Read one way, this is benign chest-beating. Read another way, it’s the beginning of a chilling endgame. Of course, it’s not like the group doesn’t have a sense of humor. “I got an e-mail from the Liberty Guard last weekend,” Krause says. “It was titled ‘Customer Service,’ and it had this operator sitting there, and somebody’s calling in and he’s telling them: ‘Press one for English. Press two if you need to learn English.’” Krause stifles his chuckle with another strip of bacon. Another slug of coffee. And a request to our waitress. “Excuse me,” he says in subdued tones. “Can I get some cha-pot -lay?” This last word he sounds out phonetically. “ Gracias.”

A local conservative organized the “Can You Hear Us Now” protest against media bias in October 2009. It spawned 53 similar rallies across the country.

Image: Michael Cogliantry

We live in a state with a sharply divided identity. There’s the Oregon of the I-5 corridor, the Portland-Salem-Eugene trinity with its über-green living, its abortion clinics, bicycles, indie rock, and gay mayors. This is the Oregon most people know: a liberal, increasingly insular biodome constantly replenishing itself with creative transplants from California and New York City. But outside of this crunchy little ventricle, the rest of the state runs various shades of red. Barack Obama may have crushed John McCain in the 2008 presidential election by 1,037,291 to 738,475 total votes, but when you break Oregon down by county, McCain steamrollered the future president 23–13, with most of those outposts of Republicanism lying in the state’s eastern and southern reaches.

It’s in towns like Ontario and Baker City and Lakeview, where wide-open swaths of rugged land spread out like the backdrop of a Peckinpah Western, that the militia movement first took hold in the Northwest in the early 2000s. And while it never died out completely, now, nearly a decade later, the sometimes sardonic, sometimes bitter, sometimes militant antigovernment sentiment that spawns such groups is once again on the rise in Oregon. And buoyed by the mobilizing power of the Internet, the white-hot rhetoric of Fox News, and, potentially more important, the galvanizing public protests of the nebulous antigovernment Tea Party movement, the anger and frustration of a newly disempowered Right could shatter the seals on the liberal biodome like never before.

There may be only around 70,000 registered Republicans in Multnomah County (compared to 250,000 Democrats), but they’re proving their ability to mobilize en masse. When local conservative radio host Victoria Taft exhorted listeners of her eponymous KPAM show to show up in droves for last year’s Tea Party tax-day protest at Pioneer Courthouse Square, Portland answered with a crowd that Taft estimated to be between 5,000 and 7,000 people—the fifth-largest gathering in the country that day (the Oregonian reported a crowd of approximately 1,000).

Such gatherings, of course, are part of a long American tradition of venting political dissatisfaction. But the rising anger over our country’s direction also has more ominous edges. This past August, the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), a nonprofit legal organization, issued a report titled “Return of the Militias” that documents the recent and sudden surge in antigovernment militia activity across the country. During the past two years, one law enforcement agency has documented the creation of at least 50 new militia groups, ranging from individuals spewing hatred about the government in general and the president in particular, to friends on private websites, to far more imposing armed bands made up of present and former police officers and soldiers. Over that same period of time, the bureau’s National Instant Criminal Background Check System (a prerequisite for a legal gun purchase) has reported well over 12 million checks—more than in any year since background verification went into effect in 1998.

The SPLC identified six local organizations with militia or antigovernment leanings: the Oregon Militia Corps, a seemingly web-based entity in Portland; Emissary Publications in Colton, which specializes in books and tapes about the New World Order; the Southern Oregon Militia, which boasts a membership of 800 based in and around Eagle Point; Freedom Bound International, which runs web- and podcasts on topics of individual freedom from Klamath Falls; the Constitution Party in Aurora, whose platform urges citizens to arm themselves “for the public safety”; and the Stayton-based Embassy of Heaven, a “Christian patriot” outfit based solely on a God-centric rule of law. Only two states—California and Texas—had a larger number of such groups.

Mike Caputo, a supervisory special agent with the FBI, is aware of the SPLC report, but, at least so far, categorizes the groups as simple acts of assembly and free speech. “[We’re] very interested in any kind of intelligence to better understand the threat [of domestic terrorism],” he says. “However, I can’t give any concrete examples of increased militia activities in Oregon. The reality is that we’re talking about First Amendment–protected activity, which means we do not track it.”

But while the means and methods of the growing Tea Party and militia movements may differ, the revolutionary rhetoric coming from both camps is increasingly similar.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the feelings of disenfranchisement that seed some militia groups find more traction in those pockets of Oregon where unemployment and poverty rates are high. Klamath County, home of Freedom Bound, is suffering a galling 13.9 percent unemployment rate, while 17.4 percent of its population lives below the poverty line—the second-highest number in the state. Crook County, which voted for McCain in 2008 and has a Tea Party headquarters in Prineville, has the state’s highest unemployment rate at 17.4 percent. Harney County—home of the High Desert 9-12 Patriots, another Tea Party offshoot—is number two at 16.8 percent.

These groups aren’t just about banding together and railing against Washington, DC, though. For Krause, joining up with a militia is less about situational frustration and more about going to the nth degree of preparedness in case the worst-of-the-worst conspiracy theories he and his fellow members believe in actually come to pass (for instance, a United Nations takeover of the United States). For Carl F. Worden, a liaison officer for the Southern Oregon Militia, taking a stance with a bit more teeth is about maintaining a last line of defense for “we the people”—even if that means defying the local government.

“Alabama Governor George Wallace found this out the hard way when he wanted to enforce segregation in schools,” Worden posted in September on the website for the Federal Observer, whose stated goal is to “keep watch over the continual indiscretions of our ‘beloved’ Federal Government.” Worden’s post continues: “The National Guard soldiers who reported for duty stood against [Wallace’s] wishes and in support of federal policy. We do not support racism in any form, mind you, but that lesson in loyalty did not escape us. Only the volunteer citizen militia is a true state citizen militia, and the State of Oregon refuses to acknowledge us. So be it.”

David Neiwert, the Seattle-based author of the 1999 book In God’s Country: The Patriot Movement and the Pacific Northwest, pinpoints the flowering of Oregon militias to the Klamath River controversy of 2002. That year, during a severe drought, the water that fed a quarter-million acres of farmland in the basin had been shut off by the Bureau of Reclamation in favor of maintaining the health of the region’s suckerfish and the coho salmon runs. According to a 2007 Washington Post article, “Farmers and their families, furious and fearing for their livelihoods, formed a symbolic 10,000-person bucket brigade. Then they took saws and blowtorches to dam gates, clashing with US marshals as water streamed into the canals that fed their withering fields, before the government stopped the flow again.” Eventually, then Interior Secretary Gale Norton—with ample prodding from Vice President Dick Cheney—used a report from the National Academy of Sciences that said the fish wouldn’t be affected by lake levels to justify resuming water service to the farmers. Neiwert says these rallies and protests, filled with members of a disenfranchised populace, became a recruiting ground for the patriot movement, a fevered call-and-response that’s now being repeated on a national level in the burgeoning Tea Party movement.

“There’s no doubt that militia members are part of the Tea Party crowds,” says Charles Johnson, editor of the influential Right-leaning blog Little Green Footballs. Johnson made national headlines when, in November, he publicly disassociated himself from the Right with a 10-point manifesto. One of his reasons? The Right’s support of “antigovernment lunacy,” including militias and Tea Parties. “I’ve published photos of people holding militia signs at the 9/12 Tea Party in Washington, DC, for example.” Johnson points out that some meetings are even being infiltrated by neo-Nazi groups. One such group, Stormfront, has even posted advice on its website about how not to look like a white supremacist in order to lure more people into accepting their handouts. Tips include: “Cover up your tattoos” and “Leave the Dixie flag at home.”

Image: Michael Cogliantry

Eight years ago, tales about FEMA concentration camps, President Obama’s forged birth certificate, and grandpa-killing death panels (some of the more popular conspiracy theories in the Tea Party universe) would have been relegated to the most ill-lit hollows of the political spectrum or considered plotlines worthy of The X-Files, but they are now treated as legitimate talking points. Far-right-wing radio has given them a voice, and thanks to constant regurgitation in prime time (mostly on Fox News), the idea that something like the successful Cash for Clunkers program was really a government plot to infiltrate our private computers now has legs. Enter Glenn Beck, the white-haired wonder boy from Mount Vernon, Washington, whose red-faced, tearful pontificating about love of America and fears of a socialist takeover has become the defacto PR machine for Tea Party gatherings. Nothing better illustrates Beck’s growing influence than his successful promotion of the Taxpayer March on Washington, DC, in September 2009. It drew a staggering crowd of at least 75,000.

Even someone as mild mannered and well intentioned as Krause, who fancies himself more of a Mark Levin man (a conservative radio host and author who’s described by Krause as “semi-caustic and funnier than shit”), subliminally sprinkles his political conversation with Beck-isms. “[This country] is like a frog in a pot of water,” he says, echoing one of Beck’s infamous analogies. “The heat’s being turned up, and people aren’t jumping out.”

“I’m hearing Glenn Beck say things to his audience of millions that I used to hear Bo Gritz and John Trochmann tell small crowds of maybe a hundred,” Neiwert says, referring to two of the most well-known and controversial militia leaders of the 1990s. “It’s a toxic environment, and it’s creating a toxic response.”

For the most part, the extreme Right’s anger gurgles up relatively harmlessly on the Internet as virtual trash talk. The MySpace site of the Rogue Nation Eternal Militia, Oregon Chapter, serves as a typical example: videos of armed training exercises, antigovernment screeds, members posing with their guns, quotes from the Founding Fathers, and, of course, the perfunctory staple of many of these sites, chicks in bikinis. The Western Oregon Militia’s site has all of those things, as well as a doctored photo of President Obama dressed as a witch doctor—complete with a bone through his nose.

But in other cases, the rising anger has taken more ominous forms. In April, a man in Pittsburgh opened fire on police officers, killing three. His friends said he feared that Obama would take his rights and his guns away. In September, Newsmax, which bills itself as one of the nation’s leading independent news sites—former vice presidential candidate Sarah Palin cited it as one of her preferred news outlets—posted and then quickly pulled a column suggesting a military coup against Obama was in order. In October, a group identifying itself as the National Militia, Soldiers for Freedom posted a video warning the president to leave the country immediately. “If you stay,” read the video message, “‘we the people’ will systematically dismantle you, destroy you, and reclaim what is rightfully ours.”

Most of the people behind these tactics are “incompetent bumblers,” Neiwert says. “But they have the capability to attract people who are competent—usually people with military training. That’s when they become dangerous.”

Of course, the best-known example of such fevered hate meeting ice-cold skill might be Timothy McVeigh—the decorated veteran of the Gulf War with a fierce antigovernment bent who killed 168 fellow Americans in Oklahoma City in 1995. Just six months earlier, the Southern Poverty Law Center had contacted then Attorney General Janet Reno with concerns very much like those the group raised this past August—that the rise of armed groups and those who hate was a “recipe for disaster.”

Victoria Taft’s conservative talk show on KPAM now has 176,000 listeners in Portland. “People have a general caricature of who a conservative is–an intolerant, gay-bashing nutball. We’re not,” she says.

Image: Michael Cogliantry

"Militias?" Victoria Taft winces, like the word is causing her a molten fit of indigestion. “They’re dumb. I have no use for them.”

Sitting inside a Peet’s Coffee in Southeast Portland, Taft, sporting a black blazer and a blonde bob as sharp as her air of authority, expresses her frustration with government both national (“Do you want the government to run your life, cradle to grave?”) and local (“one-party rule”; “corruption”; “Kulongoski kissing up to labor unions”; a city hall that doesn’t “want you to buy a car”). A dreadlocked girl sitting nearby puts down her copy of Bob Woodward’s Plan of Attack and begins blatantly eavesdropping with a look of mock horror on her face. Taft is used to the reaction.

“I don’t walk with a swagger,” she says, cordially ignoring her ever-buzzing BlackBerry. “But I’m not afraid of it, either. People have a general caricature of who a conservative is—an intolerant, gay-bashing, pro-death-penalty nutball. We’re not.”

Portland’s appetite for Taft’s brand of punditry seems insatiable. And with liberal holdout Air America’s recent bankruptcy, conservatives now own the radio dial. Rush Limbaugh holds down the top-rated AM station, KEX 1190. KXL-AM—number two in AM ratings—is home to Lars Larson, Glenn Beck, and Michael Savage. And Taft’s own KPAM pulled down a solid 2.5 rating in December, meaning that more than 176,000 Portlanders were listening to her. The competition for red radio is so intense that this past September, 970 AM changed its name to the more patriot-baiting moniker “Freedom” 970. The station plans to roll out programming from A-list right-wing talkers Sean Hannity, Mark Levin, and Laura Ingraham.

“We just need people digging and finding out what is really going on with our government and saying it out loud,” Taft says. “Once they know, they’re usually pissed off because they’ve been lied to.”

The biodome’s growing conservative movement also has quieter, less visible, but no less effective, faces. Bob (who asked that we not use his real name) sits high up on the food chain of one of the city’s biggest and most well-known employers, where he works with international clients. The 37-year-old says that while coming out as a conservative might not get him fired, it would make relations at the office awkward. “Part of me would love to be able to get into political discussions at work,” he says. “But I’d take so much crap.”

That hasn’t stopped him from becoming a firebrand among Portland’s virtual activists. Flush with pride after hearing friends’ reports of the 75,000 like-minded people at the Taxpayer March on DC (what he calls the “Conservative Woodstock”), Bob flipped on the television to see news reports saying that only a few thousand protestors had shown up on the National Mall. “That was a crescendo for me,” Bob says. “We’re doing the right things to be heard, we’re not attacking, we’re generally positive, and unlike, say, a G-20 protest, we cleaned up our mess. It was a punch to the gut.”

So Bob started a Facebook page to voice his frustration. He tossed out the idea of picketing the local Portland media, which he felt had an obvious liberal bias. Within an hour, he was getting requests from other people around the state who liked the plan and wanted to do the same thing in their towns. Two weeks later, 7,200 fed-up conservatives had joined his page and his brainchild—a “Can You Hear Us Now” march on the media. Here in Portland, a mere 100 people showed up to parade from the offices of the Oregonian to KGW studios at Pioneer Courthouse Square. But Bob’s effort spawned 53 similarly loud but peaceful events all across the country.

These are the kinds of gatherings that Neiwert calls a breeding ground for militias. Maybe there’s something vaguely menacing in the handful of protesters carrying “Where’s the Birth Certificate?” signs and yellow “Don’t Tread on Me” flags. But mostly, watching the protesters lug their handmade posters up SW Sixth Avenue, some with their kids in tow, one doesn’t feel especially threatened. “Environmentalists aren’t compared to eco-terrorists, so why do we all get thrown in with the McVeigh-militia people?” Bob asks. “I see these protests as a positive. They help give voice to lots of frustration. We’re helping people get it out of their system. We are not all wingnuts.”

And in fact, in a sign of the rapid maturation of the Tea Party movement, it’s already held its first national convention in Nashville this year (with Sarah Palin as the keynote speaker), while in Florida, Marco Rubio—a rising star on his state’s Tea Party circuit—will duke it out in the Republican primary for the right to a spot in the US Senate. So far, Oregon’s Tea Party is holding to a policy of not endorsing candidates. But three Republicans—Doug Keller, Rob Cornilles, and John Kuzmanich—running for Oregon’s 1st Congressional district seat (now occupied by a vulnerable Democrat, David Wu) have aggressively courted the partiers’ audience. All three spoke at the Labor Day Tea Party. Last September, when Keller announced his intention to run, his reasoning typified the movement: “Instead of just complaining, I decided that it was time to step up and do something.” Tucked underneath his campaign logo—a “Don’t Tread on Me” flag—is his motto: “Join the resistance.”

Somewhere in Garden Home, William Krause must be smiling at Keller’s moxie. “A lot of the general public is willing to live in a socialist society and have the government run everything,” he says. “But America is supposed to be ‘by the people, for the people’—not by the government, for the government.”