Becoming Nicole

It’s an utterly dreary January night, and inside a community meeting room at First United Methodist Church in Southwest Portland, members of the local chapter of Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays (PFLAG) are settling into folding chairs for their monthly get-together. A modest crowd of around 30 waits beneath the glaring ceiling lights for the evening’s two keynote speakers. Tonight’s topic: “Transitioning on the Job”—or, perhaps more to the point, how to come out as transgender in the workplace without losing your mind.

The crowd is made up of a few older gay men, gay teens paired up with their parents, and a smattering of men and women in various states of gender transition. More than a few of the burly, formerly male physiques are draped in anachronistic dresses from the early 1980s, clangy arm bangles, and costumey wigs (one recalling the muumuu-and-pearls-wearing title character played by Vicki Lawrence on the sitcom Mama’s Family). One female-to-male attendee is dressed in a green T-shirt and Carhartt work pants. She later tells the group that she’s worried about coming out as transgender to her boss—though it’s hard to imagine it will come as much of a shock.

Around 7 p.m., one of the speakers, Nicole Kintz, enters through the side door. She’s all smiles in a cropped khaki blazer and knee-length black skirt, red plaid scarf and slip-on black flats. Thin and trim, her formerly muscular baseball-player’s body has assumed a more lithe form. Her blue eyes are accented by dark eyeliner and light lipstick, and her brunette bobbed wig appears to be unfazed by the rain outside. Kintz exchanges some handshakes and hugs and, after introductions, assumes a teacherly stance at the front of the room.

“Wow,” she jokes, “this really is a church. No one is in the front row.” She’s instantly at ease, pacing back and forth, her French manicure highlighted by her expressive hand gestures. Seeing her up there is a little weird for me, not only because the last time I saw Kintz teach, she was a man, but also because of how familiar the whole thing feels. Her movements, her cadence, her corny jokes—they’re all Nick Kintz, my senior-year high school math teacher. It’s still him—but it’s not—but it is.

Kintz speaks for 30 minutes, then opens the floor for questions. Nothing is off-limits. Her childhood obsession with twirly dresses, her clandestine dress-up sessions, how she still loves her now ex-wife and her three kids, the pain of her divorce, her hormone regime, her penis (yup, she still has it), and, most important, what it was like to tell her boss last year that she’d be coming back from summer break to teach math as a woman.

“So … did anyone at work suspect you? Like, your students?” asks a straight-looking fellow in his 40s.

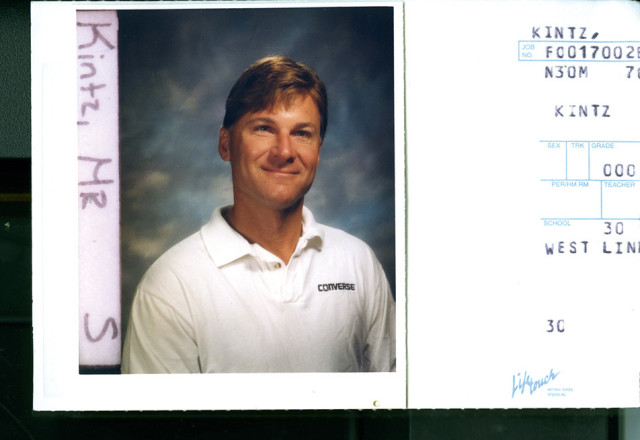

Kintz as a West Linn faculty member.

Image: Michael Cogliantry

Kintz smiles. “Well, maybe Stacey can answer that.”

There’s an awkward silence, and then I realize she’s talking about me. “Oh, well … no,” I say, stammering. The floor squeaks with the shuffling of folding-chair legs. Everyone in the room has turned to look at me. “I can safely tell you,” I finally begin, “we didn’t suspect Mr. Kintz of being a woman. We thought he was a bit on the nerdy side. But a woman? No.” The line earns me a laugh from the crowd.

Kintz has time for one more question from the group. A small woman with close-cropped hair and thin-rimmed glasses stands up. She’s wearing a 1950s-style Western shirt and a name tag that reads “Probably Andrew.” “I want to say thank you so much for doing this,” she says. “I just wondered if you had any advice on coming out to relatives. I have to tell my in-laws and just don’t know how to bring it up.”

Kintz smiles again, and, with the same ease with which she ushered my recalcitrant brain through precalculus, says, “Just sit them down and tell them the truth. There’s really no other way to do it.”

{page break}

I wasn’t necessarily bad at math; in fact, I pulled in mostly As and Bs all through high school. It’s just that I hated it. So by the time my senior year at West Linn High School rolled around and I’d already decided I wanted to become a writer, my patience for multivariable equations was pretty much nil.

With his tucked-in polo shirts, khaki pants, tennis shoes, prematurely balding head, and innocent church-boy demeanor, Mr. Kintz was the perfect foil to my math-averse class clown persona. My friend Wisa and I loved to crack him up, and I could tell he loved us for making one of his five class periods less of a bore.

It had been 17 years since I’d seen Mr. Kintz when Wisa called last summer to say she had “some very big news about our math teacher.” The news—that he’d come out as a transwoman—left me emotional. I pondered how miserable he must have been all those years, and worried, like a protective sibling, that kids would be mean to him.

Turns out that Nick Kintz had been secretly living as Nicole outside of school for three years, but it wasn’t public knowledge until last summer. On August 20, parents and students received a carefully worded letter from West Linn High School principal Lou Bailey that said Nick would be returning to school in the fall as Nicole. “While understanding the complexity of the situation, we fully believe that this presents the opportunity for a teachable moment for our students, this community, and ourselves” Bailey wrote. “As educators, we stand for tolerance, authenticity, honoring diversity, and developing character.”

Kintz in the expansive walk-in closet of her Milwaukie home.

Image: Michael Cogliantry

For Kintz, this wasn’t about realizing some kinky hobby in public view. Unlike drag queens and kings, who often dress as women and men for fun or fetish, transgender people like Kintz not only want to dress this way, they want to live and ultimately function in society as the opposite gender. Transgender people typically struggle with a feeling that their biologically assigned gender fails to describe who they really are—what the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) currently describes as “gender identity disorder.” This has little or nothing to do with sexual preference. Recent findings suggest there may be structural differences in the hypothalami of transgender people, meaning that the misalignment of physical appearance and gender identity may start in the womb. Scientists theorize that for some people, that sex-differentiated area of the brain develops to more closely resemble that of the opposite sex.

While the biology of gender continues to crystallize, experts can offer only vague estimates of how many among us are transgender. It might be as rare as 1 in 2,000. Or it might be 1 in 100.

By the spring of 2009, Kintz’s need to go public had become urgent. After a four-year regimen of oral hormone therapy (spironolactone, a testosterone blocker, and estradiol, an estrogen that promotes breast growth), her A-cup breasts were beginning to defy the camouflage of baggy sweatshirts. She was also finding it increasingly difficult to curb feminine mannerisms, like saying “honey” in class. “I’d catch myself doing that a few times a day,” Kintz recalls. “It really stressed me out.”

Lucky for her, the law was on her side by then. Effective January 1, 2008, the Oregon Equality Act added protection for sexual orientation, which includes gender identity, making it illegal for the district to fire her. The bill put Oregon on a short list of only 13 states (plus Washington, DC) where gender identity discrimination is illegal. “It helped make my decision,” Kintz says. “I don’t think I would have risked losing my job had that law not been in place.”

Comforting as this progressive bit of legislation might have been, Kintz was still “scared shitless” at the thought of going public. And for good reason. She’d heard horror stories of transgender teachers being forced to change schools, or losing work. Take the story of William McBeth, a beloved substitute teacher in Eagleswood Township, New Jersey, who became a woman in 2005 and was forced to retire due to a sudden dearth of gigs. And then there’s the community outrage. In 2008, in Vacaville, California, parents pulled their kids from an elementary school music class after the teacher transitioned from female to male. “Understandably, a lot of teachers go stealth,” Kintz says. “But I wasn’t going to do that. How is anybody going to learn? If not me, who? If not now, when? Besides, I’d already put in 20 years at the school. I didn’t want to start over somewhere else.”

Kintz’s coming-out process began officially in June 2009, when she alerted her union representative from the Oregon Education Association (OEA), Karen Spies, of her plans to go public. Spies then set in motion a series of meetings with the district to make sure this revelation was handled as prudently as possible.

Spies explains that there was no union precedent for advising transgender teachers, nor do they keep records of teachers in Oregon who have transitioned on the job. “You don’t want to get into profiling,” she says. “These are handled case by case.” As far as Kintz knows, she’s the first teacher in Oregon to transition in the workplace. At the very least, she’s been the most public about it—though that wasn’t exactly her call.

Spies and district officials all agreed that to protect Kintz—and to minimize disruption to students—media coverage should be limited or, ideally, avoided. Kintz was happy to oblige. But on August 27, as Kintz enjoyed the last remnants of summer vacation at home, her friend Sara called to say that her husband had been listening to Lars Larson’s KXL show and there was talk of a transgender teacher in West Linn who had apparently come out in a letter sent to parents. Kintz flipped on the radio, and what she heard made her heart sink. For two days, she was the subject of an aggressive discussion about whether a transgender person should be allowed to teach kids.

“Most callers agreed with me that someone with that kind of psychological malady shouldn’t be teaching at all, let alone [teaching] impressionable teenage kids,” Larson tells me over the phone in March, seven months after the show. He reads me the entry on gender identity disorder from the DSM-IV, punctuating it with a question: “How can we allow someone who is making chemical and surgical alterations to their body to teach our kids?”

“What about teachers who take medication for depression, or who have had nose jobs or breast augmentation surgery?” I counter.

“It’s about an agenda to make decisions about our children’s sexual health,” he continues, going on to compare Kintz’s situation to that of a convicted murderer being allowed to teach kids after leaving prison. “If my daughter were in that class,” Larson says, “I’d strongly suggest she leave it.”

{page break}

Larson’s show dissolved Kintz’s hopes of laying low. But instead of cowering, she decided to “put a face on the story,” and with the school’s blessing, she agreed to one interview with KATU, which broadcast a short piece on the evening of August 27. Interviewed in her home, she explained why she was making her identity public. Kintz felt the story was concise, fair, and framed her as she hoped it would: a teacher who wanted to get on with her life and do her job. Stories followed in the Oregonian and the West Linn Tidings, but without any official comment from either Kintz or district officials.

On the morning of September 8, Kintz prepared as she always did for the first day of school, but this time she wore a wig, carefully applied lipstick and mascara, and walked out the door as Nicole, wearing capri pants, flats, a blouse, and a blazer. Kintz admits now that it took her three months to feel comfortable and unguarded. And aside from the occasional “he/she” pronoun confusion, she’s been amazed at how students have reacted (or not reacted) to Nicole. “I’ve never had ‘the conversation’ with them,” she says, “but I do hope at some point I can answer some of their questions, whatever they are.”

Kintz’s colleagues are relieved that her transition has been mostly a non-event. “She is so exuberant now, but also works hard at keeping a low profile,” says Lynn Pass, a close friend of Kintz’s who teaches art at West Linn. “She did what she needed to do, but understands there are people who aren’t comfortable with it.” Another colleague, science teacher Jim Hartmann, who has known Kintz for almost 20 years, admits to being “shocked” by how well students have adjusted. “I was very worried for her and her safety,” he says. “But this has gone so well that when a teacher from another school asked me recently how ‘that whole situation turned out,’ I honestly didn’t know what they were talking about.”

How can we allow someone who is making chemical surgical alterations to their body to teach our kids?

—Lars Larson

Despite what could rightly be dubbed a rousing PR success, the district is still skittish about media coverage. While Kintz has been open and honest about her experience, administrators wouldn’t allow her to be observed in class or condone any on-campus interviews with faculty, all to “protect Nicole’s rights.” Kathe Monroe, the district’s director of human resources, says it’s simply not in her job description to “have an opinion about any of this,” but that she’s “proud of how we all came together.”

Amanda Christy is a graduating senior who switched into Kintz’s class at the beginning of the year, not to experience the novelty of having a transgender teacher, but because she liked Kintz’s teaching methods. “She goes way beyond what is expected,” Christy says. She cites a section on Kintz’s website where students can watch videos if they missed class, and the way Kintz encourages students to rate homework assignments on a scale of 1 to 6 to help gauge the efficacy of certain lessons. “She genuinely cares,” Christy says, “which makes me try harder. I want her to feel like her efforts are noticed.”

Another graduating senior, Natalie Snyder, is a devout Catholic headed to the very Catholic University of Portland (Kintz’s alma mater) next year. She confesses to having been “a little close-minded about this stuff.” Last September, as school halls first filled with clanging lockers and gossip, she recalls whispers of, “Have you seen her? Is the rumor true? Does she still look like a dude?”

“Yes, I was nervous about how the rest of the year would play out,” Snyder says. “But I realized the only difference was her clothes; she is the same person. I also think our generation—we’ve been exposed to so much more diversity, it just wasn’t a big deal.”

It’s November 2009, two months before the PFLAG meeting, and I’m waiting for Kintz at the Blue Moon Tavern & Grill on NW 21st Avenue. I haven’t seen my former math teacher since December 1992, when I stopped in for a chat on winter break from college. For some reason, I feel nervous—like I’m going on a blind date.

Through the window I can see her cross the street and open the door. She’s wearing a black skirt, blazer, and brown bobbed wig with bangs. And you know what? She looks pretty damn good. I don’t remember Nick having such pretty blue eyes.

{page break}

We order drinks, settle into a booth, and she tells me her story from the beginning. Kintz grew up one of 11 children in a “loving home” in the tiny town of Sublimity, Oregon, dutifully attending Catholic mass every day. She tells a story about how, when she was 5, she and her younger brother tried on some of their sisters’ clothes, just for fun. “I had on the prettiest flower dress that twirled when I spun around,” she remembers. “The next day, when my brother said ‘No way’ to doing it again, I realized, ‘Oh shit, this probably isn’t good.’” As Nick matured, so did his desire to feel more feminine. The daily internal war between how wrong he felt in his skin and the “eternal damnation” his Catholic upbringing told him he’d face if he ever came clean was in full roar.

Despite his emotional turmoil, while in college Nick met and fell in love with Kim, a nursing student from Pendleton. She was his first serious girlfriend, and the two married on September 29, 1979. Confident in his heterosexuality, Kintz hoped that marriage and children (the couple had two sons and a daughter, now ages 26, 23, and 19, respectively) would “cure” him of his urges to live his life as a woman. But it only made the lies deeper and more painful. Kintz says he cried himself to sleep most nights. Seventeen years would pass before finally, in 1996, he confessed to Kim the secret he had never uttered to another human being.

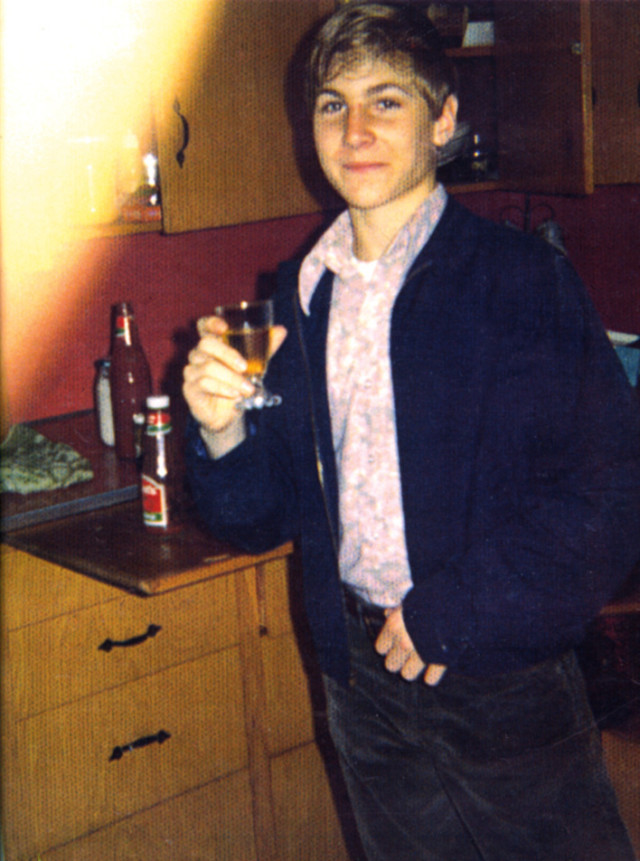

Kintz, 15, stands in the kitchen of his family’s home in Sublimity, Oregon.

“Kim’s response was, ‘That’s all?’” Kintz remembers. “We really thought our love for each other was bigger than this thing.” The resolution seemed simple: Nick would dress as Nicole when he needed to, and the marriage would continue as planned.

It worked. For a while. The years that followed brought some highs—keeping the family together—but a lot of lows. As Kintz remembers it, Kim tried, but she could never really compete with Nicole for Nick’s time and attention. There were a lot of close calls, too, like the time their younger son came home early and, in a panic, Nick forgot to remove the earrings from his ears. (He kept fishing line in the holes to prevent them from closing up.) The charade was exhausting, and in 2006, after 10 years of trying to negotiate an impossible situation, Nick moved out. In January 2008, the divorce was final. “I think Kim got tired of my mood swings,” says Kintz. “She was the one who decided to end it. I never wanted to divorce.” Kintz says the pain of losing Kim, “the love of my life,” has been at times unbearable.

Kim declined to comment for this story, but wrote via e-mail: “It has been a difficult transition for our family … a very personal situation to me. I choose to keep it private.” The Kintzes’ daughter, Kendra, who’s studying industrial engineering at Oregon State University (all three kids are engineers), says her mom is doing “exponentially better now.” “I’m also a lot closer with both my parents after all this,” says Kendra, who still refers to Nicole as “Dad.” “He is so happy now. He was never really emotional before, and now it’s just pouring out of him. All it takes is five minutes to see how genuine he is. I mean, how could you not want to support that?”

Back at the Blue Moon, we’re on hour three, and we’ve tackled every topic except, well: “My bottom surgery?” Kintz says. “Yes, I hope to do it. When I get dressed in the morning, there’s a sense of ‘Which one of these things doesn’t belong?’ I do feel very incongruous, but I’m not in a huge hurry.” And she can’t be: protocol that’s known in the medical field as the Harry Benjamin Standards of Care (named for the Berlin-born physician who, in the 1950s, was one of the first doctors to treat and write about transsexuals) advises transgender people to live openly and consistently in the desired gender role for at least a year (for Kintz, that would be this July) before undergoing sexual reassignment surgery. And it’s not cheap. The procedure can cost upward of $26,000, and it’s not covered by most insurance policies.

By 10 p.m., we’ve been gabbing for nearly three hours, and I tell Kintz it’s probably time to wrap up. It’s a school night, after all. “I’m telling you,” she says, “this is the riches of life, sitting here reconnecting with my past as the person I always wanted to be. It’s like Christmas every day.”

{page break}

Oregon has earned headlines more than once on the transgender news front. The tabloids went nuts in March 2008 after a Bend man named Thomas Beatie announced via the Advocate that he was—drumroll, please—a Pregnant Man. Born a woman, Beatie transitioned from female to male, but kept his reproductive organs so he could give birth. He is currently pregnant with his third child and due to give birth again sometime this year.

In November 2008, the former lumber-mill town of Silverton elected the nation’s first transgender mayor, Stu Rasmussen, who trounced his opponent by 13 points. “I’d always wanted cleavage, so I went out and acquired some,” he told KGW after his victory. Despite being criticized for dressing a bit too revealingly in low-cut dresses and miniskirts, Rasmussen, who identifies as male and female, has been lauded for his fiscally conservative, no-nonsense mayoral style.

Kintz’s transition has been far less publicized, but its effects are still reverberating throughout the Portland community. She’s received an outpouring of support from students, parents, colleagues, and former pupils, some of whom have come out to her as gay or transgender themselves. She’s also aligned herself with various advocacy groups in Portland, which she says have embraced her for being a “warrior,” and she’s started a part-time gig of sharing her story in public forums. “I finally realize what I’m doing now is a higher cause,” she says. “I’m thankful I finally know this.”

Kintz has also made peace with “the whole church thing,” which is to say she hasn’t set foot inside one in over a decade. “If God knows everything, and he knew what I was going through, why would I be born if I was just going to go to hell?” she wonders. “If church brings peace to people, that’s great. It just didn’t do that for me.”

While Kintz has gone through the fire to reach a peaceful point in her life, there are some in the transgender community who feel that such public transformations lead people to believe that transitioning between sexes is merely something to gawk at.

“We just want to go the grocery store and get on with our lives,” says Laura Calvo, a transgender woman (and former Josephine County deputy sheriff) who was elected treasurer of the Democratic Party of Oregon in 2009. She is a frequent sounding board for transgender issues in Portland. Calvo commends the school district for how it handled Kintz’s transition, but she’s quick to point out that Kintz isn’t the first teacher to do this, nor will she be the last. Transgender people, she says, are everywhere.

“We are in Obama’s government and corporate America. We drive buses and police cars,” Calvo says. “The more we make of each person’s transition, the more we continue highlighting how ‘different’ we are. It’s a constant battle between our privacy and ‘bravery.’ But as I constantly remind people, it’s not brave what we do; we simply have no choice.”

For the first time in her life, Kintz lives by herself, and she’s been dying to show off her Milwaukie bachelorette pad. I can tell she’s relishing her independence as she leads me on a tour of the spacious walk-in closet—one of her favorite parts of the house. Hangers fill every inch of rack space, each one draped with blouses and skirts bought at thrift stores (creating a whole new wardrobe on a teacher’s wages isn’t easy). These days, she rarely wears pants. “It reminds me too much of the guy thing,” she says. Below the racks are a small makeup table, a mirror, and two styrofoam heads topped with the wigs her male-pattern baldness make essential. “I love sitting here, just being in here,” she says. “I wasted money on cheap wigs that never did look very good. Now I buy quality, and it is so worth it!”

Back in the family room, Kintz kicks off her flats and relaxes into a leather recliner. She wants to show me a DVD someone made of her giving a lecture the week before to a human sexuality class at Portland State University. A crossed leg reveals a run in her stockings as she cracks open a Heineken Light. She may be new to womanhood, but she’s already got the whole calorie-consciousness thing down.

The wall-mounted plasma screen lights up with the image of Kintz standing in front of a chalkboard inside a packed college lecture hall. “I get such a kick out of seeing myself in this,” Kintz says, taking a swig of her beer and chuckling. “It’s so wild! God, I’m such a teacher, aren’t I?”

As I watch her watching herself—her pacing, her hand gestures, her charm, her self-deprecation—the fear for her well-being that overcame me last summer when I first heard about her transition from Mr. to Ms. Kintz is replaced by an overwhelming sense of gratitude. I was just one of Kintz’s many students from just one of his many math classes so many years ago, and yet here I am witnessing firsthand the anatomy of a second chance.