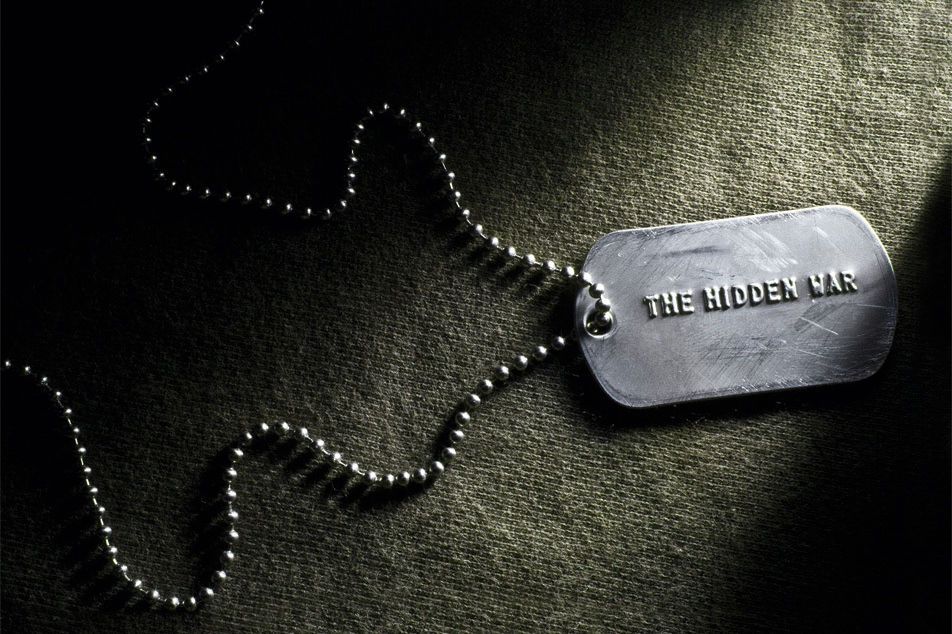

The Hidden War

DRENCHED BY 30 INCHES OF RAIN A YEAR, Roseburg’s rolling, fir-covered hills wrap around 59-year-old Carrie Jones’s home like a berm protecting her against memories of desolate, sun-scorched texas, where she spent her short military career in the 1970s.

The desert, for Jones, holds the danger.

It’s where fellow US Army soldiers drilled holes in the bathroom walls to watch Jones shower; where her commanding officer locked her in his quarters and forced her to watch pornography with him; where a group of pilots on a training exercise took turns raping her. It’s where soldiers put a pillowcase over Jones’s head, took her to an isolated barn, strung her up by her hands, cut her clothes off, and assaulted her, calling it “Prisoner of War” training; where they left her hanging for so long she had to have tendon surgery and was never able to play her beloved clarinet again. It’s where, a few months before her enlistment ended, Jones’s commanding officer drove her to a remote area of Fort Hood and raped her in the middle of the day.

Jones (who prefers her real name not be used) entered the army in 1974 at age 21 and rode a wave of post-Vietnam military gender integration into the First Cavalry Division. When she enlisted, Jones says she was a “happy person,” a confident practical jokester who, in training, once installed a speaker in a fire hydrant to surprise passersby.

“I came back a different person,” she recalls during a conversation inside a suburban Starbucks, her right hand nervously rubbing her thigh. “And it was our side that did it to me.”

Nearly 40 years later, Jones is still living with the effects of the attacks she suffered while wearing the United States’ uniform. Today, she figures as an early—if perhaps extreme—example of a hidden plague within the US armed forces: an epidemic of sexual assault against servicewomen.

For decades, veterans like Jones survived largely in silence, but that’s slowly changing. In 1992, the Senate Veterans Affairs Committee recognized a new medical term: military sexual trauma, or MST. The definition: “psychological trauma, which in the judgment of a VA mental health professional, resulted from a physical assault of a sexual nature, battery of a sexual nature, or sexual harassment which occurred while the Veteran was serving on active duty or active duty for training.”

The VA estimates that roughly 20–30 percent of women who have served in the military report experiencing some form of military sexual trauma. The Department of Defense reported that in 2010 alone, current military personnel filed 3,158 reports of sexual assault on both men and women. (MST affects a larger percentage of females in the armed forces, but it remains a concern for men, too.) Moreover, a study published by the DOD estimates that as many as 85 percent of sexual abuses go unreported.

In recent years, with the US embroiled in conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere, the numbers, visibility, and importance of women in the military have increased. They currently make up 14 percent of the armed forces, a number that is projected to grow to 20 percent by 2020. In 2008, Ann Dunwoody became the nation’s first female four-star general. And this past winter, the Military Leadership Diversity Commission recommended that the military end its ban on allowing women to serve in direct combat roles. Yet the military and government are only now coming to grips with the pervasive problems caused by MST.

“There’s more shame, secrecy, and stigma attached to post-traumatic stress disorder associated with military sexual trauma than with combat-related PTSD,” says Marcia Hall, a counselor and Women’s Health Program manager at the Roseburg VA. “It’s a hidden war.”

As servicemen and women return from conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, stories abound about the injuries suffered in combat: about the improvements in medical technology that spare lives when roadside bombs take limbs. About the post-traumatic stress disorder that comes with watching a best friend’s Humvee disintegrate into a fiery metal pulp 10 feet away. About how this generation of vets compare with their Vietnam-era counterparts. But we hear less frequently about the injuries female soldiers, specifically, suffer—sometimes at the hands of their male comrades.

“Every year the rates of MST have risen,” says Sonja Fry, a social worker and MST counselor at the Eugene Behavioral Health Recovery and Reintegration Services office. “This generation is a lot more open; they’re allowed to talk about it more. The problem is not going away anytime soon.”

Oregon finds itself on the battle lines. Despite not having an active military base, our state is home to more than 25,000 female veterans, 7,000 of whom are enrolled in the Portland VA’s Women Veterans Health Program. Last September, Portland’s VA opened the Women Veterans Health Care Facility, the first female-only VA clinic in the state and one of few in the country. This spring, Oregon lawmakers passed legislation calling for improvements in both the scope and quality of health care available to veterans affected by MST. (see Codifying Care) Nationally, Congress’s 2010 Caregivers and Veterans Omnibus Health Services Act included a provision specifically asking for better care and treatment of MST. In February, spitfire DC attorney Susan L. Burke—whose clients include victims of torture at Abu Ghraib—filed a lawsuit on behalf of 17 former and active duty service members, including two men and two Washington state women, alleging the Department of Defense, namely Secretaries of Defense Robert Gates and Donald Rumsfeld, failed to prevent, investigate, and prosecute the perpetrators of rape and sexual assaults.

The health consequences of military sexual trauma are severe: insomnia, depression, substance abuse, and even death. A 2010 study by researchers at Oregon Health & Science University and Portland State University found that male veterans are twice as likely as nonveterans to take their own life, while young female veterans are three times as likely. And according to a 2009 study in Clinical Psychology Review, sexual trauma is actually more likely to result in stress-related physical and psychological ailments than combat trauma.

In other words, psychologically, you might be better off seeing your buddy blown up than being raped.

The Department of Defense has created new programs to raise awareness, from annual sexual assault summits for high-ranking officers to a recent social marketing campaign—“Hurts One. Affects All”—aimed at encouraging soldiers to help prevent the sexual abuse of their colleagues. A recent report from the DOD showed that sexual assaults against women on active duty dropped by 2.4 percent between 2005 and 2009. But the full impacts of military sexual trauma on individual soldiers are still being understood. Like Jones, a growing number of veterans are only now coming forward years, even decades, later to report past abuses, many of them unaware until recently that any service in the military (not just war) qualifies them as a veteran.

Jones’s story and those of the two other Oregon women that follow offer a glimpse of the lingering scars—as painful and life-altering as those acquired on the battlefield—MST can leave on a life.

Krista Shultz

KRISTA SHULTZ GREW UP a hundred miles east of Los Angeles, in the overcooked Yucca Valley, listening to her father tell stories about his time as an army linguist in the 1950s. To Shultz, the military was the stuff of fantasies—promising adventure, excitement, and escape from the flat-ironed stretch of highway she called home.

“After high school, like a lot of small-town kids, I wanted out the fastest way possible,” Shultz recalls. “Being a linguist seemed kind of fun, and I thought I could work for the UN or something afterwards and travel.”

After basic training in South Carolina, Shultz aced her language aptitude exam, sending her on a path to learn one of the toughest languages: Arabic. It seemed useless. This was, after all, 1987. The US military’s chief focus was on remnant Cold War animosities, not the Persian Gulf. For the next year and a half, Shultz found herself among the army’s intellectual elite, many of them women. She completed her training as an army interrogator just weeks before Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990. Then Shultz was assigned to an “air assault unit” (specialists inserted into battle zones by helicopter) based at Fort Campbell, Kentucky.

“It was the first time I’d been with a big army group,” Shultz recalls. “That was the first time I realized that the military was made up of mostly men…and, you know, those kind of men.”

Taunts peppered her evening runs around the base: “Hey baby!” “Nice tits!” During a training exercise for exposure to chemical weapons, her instructor jeered, “I hope I get to scrub you down.” Within weeks of Shultz’s deployment in the Saudi Arabian desert, the catcalls gained an ominous edge when a female soldier was raped by one of her colleagues.

“After that we couldn’t go by ourselves anywhere,” Shultz recalls, “and at night we had to have a male escort.”

Soon after, “Sergeant Scrub Down” (Shultz can’t remember his name) led 30 military intelligence infantrymen into a remote section of the desert for a training exercise. They needed an interpreter. He requested Shultz.

“I was really freaked out,” says Shultz. “We were going to be out there—on the side of a sand dune in the middle of nowhere—for three or four days, and I was the only woman.”

The first night, Shultz’s fears were confirmed. When the unit gathered around a campfire, the sergeant said in a clear voice loud enough for the entire infantry to hear, “The only reason we brought you out here was so we could rape you.”

Shultz’s survival instincts kicked in. She told him she’d shoot anyone who came near her. The soldiers laughed. And the sergeant retorted, “You have to sleep sometime.”

40% of homeless women veterans report having

experienced sexual assault during their time in the military.

With that, Shultz headed to the big tent where she and the 30 men slept, the only buffer the few feet more separation her cot had from the others. “I could see everyone, I could hear everyone, and they could see me,” she remembers. Shultz picked up her M16, methodically loaded a magazine, laid the gun across her lap and waited. For three days, she didn’t sleep; the gun was always with her, even behind the dunes that served as the latrine.

“I had this feeling of being pressed between two dangers—my people and the enemy—and neither one was safe. They could rape me and kill me and say an Arab did it and nobody would witness it,” she says. “Nothing happened to me, though, and to this day I believe it’s because I didn’t sleep.”

Shultz still doesn’t sleep—not without pills. At the end of her enlistment, only 10 months after being deployed, she could sleep only by turning on all the lights. She took a night job at a convenience store to make her upside-down schedule work.

Insomnia, according to the Roseburg VA’s Hall, is one of the most common symptoms of PTSD. But the diagnosis surprised Shultz. “I thought PTSD was what Vietnam vets had,” she recalls. “I never saw combat. I didn’t see people getting shot. I just couldn’t sleep.”

In war zones, Hall says, sexual trauma can be especially harmful because soldiers are always under threat mentally and emotionally. Often, when the victim isn’t fearful of an external enemy lurking behind a sand dune, she is afraid of her fellow soldiers. The resulting psychological trauma is akin to that experienced by children who are bullied at school and abused at home: there’s no escape and no relief. But the serviceperson’s situation is further complicated by the need for “unit cohesion”—the notion that welfare of the group, the team, must take precedence over the individual. It often precludes victims of MST from reporting assaults at all. “If you’re in a war zone, no matter what else, staying alive is most important,” Hall explains. “For MST victims, there’s the idea that if you tell anyone, you’re going destroy the unit.”

Shultz never turned the sergeant in. There was already enough resentment toward women in the Gulf, she says. But more than a decade later, after moving to Eugene, Shultz sought help from the VA. The VA screens soldiers for military sexual trauma by asking them two questions: In the military, did you ever receive uninvited or unwanted sexual attention? Did anyone ever use force or the threat of force to have sex against your will? A yes to either question qualified Shultz to receive health care for issues related to MST. It’s a relatively new standard created to ensure veterans receive treatment without having to relive or “prove” the trauma, a change that has sent the caseloads soaring for MST counselors like Sonja Fry, whose patient list hovers around 165—three times more than the recommended limit. The heavy caseloads prompted Oregon lawmakers to a pass a House Joint Memorial this spring urging Congress to mandate VA mental health counselors’ caseloads be limited to 60.

A few months after first visiting the VA, Shultz read a Register-Guard article about a soldier arrested for refusing to return to Iraq because she’d been coerced into having sex while she was there. Shultz became incensed. For the first time she revealed her own Gulf experience publicly. “I went willingly to participate in that war believing that the dangers I would face would come from the opposing side,” she wrote in a 2006 letter to the editor. “This changed the moment I was sexually harassed by a soldier who outranked me and had quite a bit of control over me. I became more afraid of the soldiers on my side of the war than I was of the enemy.”

Shultz’s path to treatment proved to be rocky. Originally, she was assigned to a male counselor, but she stopped going because she found she couldn’t confide her experiences in him. Moreover, his waiting room, which was filled with men and military décor, “triggered” her PTSD (a common concern for female veterans, according to Fry). Shultz started seeing Fry this spring and finds the Eugene counselor’s feminine office puts her at ease.

“I just started seeing her, but I’m like, where have you been all my life?” says Shultz.

Toward the end of our conversation, Shultz pulls out a tattered journal.

“I wrote about it,” she says, thumbing through the worn, tidily inked pages. “If I hadn’t written, I think I would have revised it all in my memories. So to me, this is like my 21-year-old self talking to my 41-year-old self and saying this really did happen, and it really was hard for you.”

Heather Smith

AT AGE 23, the only female Air Force jet engine mechanic in a shop run by a supervisor who blithely announced that women belong at home, Heather Smith recalls hearing the first murmurs of trouble: “They’d say, ‘We know how to tell if you’re a real redhead, you know….’”

It was 1983. Smith (who agreed to be interviewed under a pseudonym) felt her only choice was to keep quiet about the remarks. Keep her head down. Do her work. But she needed a friend, so she went out with one of her colleagues, a fellow mechanic she had met at tech school in Illinois. He seemed safe.

“I didn’t expect it,” Smith says, looking at her hands and pursing her lips. She leaves the “it”—the date rape—hanging.

In 2009, Clinical Psychology Review published a study confirming that many women who experience military sexual trauma are more likely to become victims of domestic violence as well. The study called for further research to confirm the finding. Smith could stand as evidence.

Within four months of the rape, Smith married a different airman from another shop. She didn’t talk to him about the rape or the harassment. “You just suck it up and act like it doesn’t bother you, or they’ll really get you,” she explains. Three weeks after their nuptials, Smith’s husband started shoving her around. He threatened to kill her if she told anyone. Smith got a brief reprieve when her husband was transferred to Ramstein Air Base in Germany, but a few months later she received orders to join him. She arrived in the fall of 1984, and it was only a matter of days before the pushing escalated to violent attacks.

“He’d take a hammer to me, choke me, kick me, rape me, lock me in one of the rooms in the house so I couldn’t leave,” Smith remembers, her voice trembling. “I told the guys in the shop if I didn’t show up one day, it was because he’d killed me.”

By October, almost all of Smith’s long, thick locks had fallen out.

The couple lived in Germany for five years. MPs were called to their house at least a dozen times, sometimes by Heather, sometimes by neighboring military couples concerned about the violence. But her husband was never charged with anything.

“They didn’t take any disciplinary action because they said it would hurt his military career,” Smith explains. “His supervisor even told me that basically they looked at it as if I was the problem because I turned him in.”

Eventually, Smith packed up the kids and left. Like many domestic violence stories, it wasn’t a clean break; it would take years and a move to Oregon before she fully split from her husband. But her new world came crashing down in 1997 when the cumulative effect of a decade of abuse sent her tailspinning into a nervous breakdown.

“I was just functioning less and less,” Smith says. “I’d go to work, get the kids, come home, figured I’d survived the day, and just go to bed.”

Smith checked into an outpatient mental health program through Providence that ultimately led her to be treated for PTSD at the VA. The Portland VA Medical Center prefers two treatments for PTSD: cognitive processing therapy, the talking method most people associate with counseling; and prolonged exposure therapy, a method pioneered (partly in Portland) by noted psychologists Paula Schnurr and Matthew Friedman in the early 2000s. The treatment is based on the premise that avoidance keeps PTSD going. “You get relief when you avoid the cues that remind you of the horrific event,” explains Irene Powch, a VA psychologist who specializes in PTSD. “So you stay away even more.” Prolonged exposure therapy gradually introduces PTSD sufferers to cues that might set them off in a safe environment, so they can learn a new response. For example, if a patient avoids crowds due to memories of an Iraqi marketplace where he or she saw a horrific bombing, Schnurr and Friedman’s therapy would send the patient into a crowded mall.

“You have to learn that it’s safe,” says Ashlee Whitehead, the military sexual trauma coordinator at the Portland VA Medical Center. “I have not had a veteran go through the therapy completely who hasn’t gotten something huge from it.”

But the treatment is expensive, both to administer and to train therapists in, which results in a lack of providers. This shortage was part of the motivation for the passage of SB 276 (see Codifying Care) , which encourages the VA to share specialized knowledge (like PTSD treatment) outside the VA, thus creating a larger pool of practitioners from which veterans like Smith can receive treatment.

Today, Smith lives in Southeast with her oldest daughter and still gets weekly individual and group counseling through the VA. The sessions haven’t taken away the hurt caused by 10 years of abuse, but they have helped her contend with her ongoing reactions to it.

“I guess I always felt like I was on the outside of a chain-link fence looking in at the other people. They were OK, but I wasn’t,” she says. “In group we understand each other and where we come from.”

Carrie Jones

CARRIE JONES IS POOR. In the past, she’s been homeless. She’s getting by today in Roseburg on $2,000 per month. But the army veteran can’t shop in secondhand stores. No Goodwill. No Salvation Army.

“As soon as I walk in there, I can smell that, you know, that musky man smell, and I have to get out,” she says. “It just brings it all back.”

Following the first assaults in Texas—the showers and the pornography—Jones talked first to other women (military police) on the base. They discouraged her from reporting the abuse. Women who spoke up, they warned, were shipped off to other bases or out of the military altogether. Jones feared losing her military career. (A 2003 study in the American Journal of Industrial Medicine confirms her fears, finding sexual assault often affected—and sometimes ended—women’s military careers because the victims transferred units or bases as a result, or gave up on the military altogether.) But she wasn’t deterred.

“I went to my sergeant, to the first sergeant, to the company commander, and they were very blunt,” she recalls. “They told me I’d make it harder for the women that came behind me.”

After the gang rape, Jones asked for a transfer. A gifted musician with a degree in music, she was shipped off to the First Cavalry band. But a year later, the discovery of a Russian tank with chemical weapons prompted her transfer back to her original unit for a potential mission. The assaults began anew. Even after the attack in the barn, Jones remained determined to stay in the army, believing that if she needed to, she could report the abuse to the III (Third) Corps, a kind of oversight body for the base. But that required alerting her CO.

“So when he raped me,” she recalls, “I knew they had me.”

Today every military base appoints a sexual assault response coordinator (SARC), who arranges treatment and support for victims without notifying their command. But the victim’s command must be informed to initiate an investigation. In 2010, 2,554 service members were investigated for sexual assault; though not all cases have been decided, so far 801 have received some kind of disciplinary action.

“The single factor that keeps coming up from these stories is that it really seems dependent on leadership,” says Hall. “If they have a strong leader who doesn’t tolerate it, there won’t be any tolerance in the unit.”

Broken, Jones used up her leave and quietly left the job. Three binders of paperwork, each three inches thick, documenting her hospital stays from various assaults went with her.

54% of active duty women who refrained from reporting

sexual assault cited being afraid of retaliation or reprisals

from he perpetrator.

“But if I could have found someone that could have helped me, I would have stayed for 20 years,” she says. “[The work] was very self-satisfying, like you were doing something that meant something.”

Instead, Jones spent the next 35 years wandering between Reno, Las Vegas, and Utah, changing homes every year. She stopped talking to her siblings, picked fights with her coworkers, and went on capricious spending sprees. She didn’t date, maintained very few friendships, and flew into violent rages, once throwing her furniture out of a second-story window. She never told anyone about what happened in the army. It was a far cry from the ebullient 20-something who’d joined the military. But isolating behavior is one of the hallmarks of PTSD.

“It affects the victims socially and occupationally,” MST counselor Fry explains. “On the job, they look like they’re very competent, but when they leave the job, how has life been? What kind of relationships are they having? Can they connect with a significant other?”

Jones wants to believe that the abuse she experienced in the army would not happen to the young people serving today, that officers in charge would no longer tolerate the behaviors that caused her post-traumatic stress disorder. But the stories she hears—some from women who have served in current conflicts—in her Roseburg VA support group tell her otherwise.

“I know that women in the military are still sexually abused,” she says. “And I still think if it’s officers who do it, it just gets swept under the rug.”

Sharing her own experience with military sexual abuse is, for Jones, both therapy and advocacy. She can’t go back and change the events that unfolded in the Texas desert. But if she could talk to that scared, shaken 21-year-old, she would tell her one thing, the same thing she tells young servicewomen and veterans today: “Say something. Do not keep quiet.”

Additional reporting by Eleanor R. Brown