Tilting at Landfills

Image: William Anthony

In the heart of Oregon’s picturesque farm and wine country, an 18-story mountain of trash rises next to the Yamhill River.

For two decades, Fifth-generation farmer Ramsey McPhillips and a motley crew of neighbors have waged a quixotic battle to stop north america’s largest garbage company from growing even bigger.

Who wins matters.

•••••••••••••••

Farmer and anti-landfill crusader Ramsey McPhillips

Image: William Anthony

FOUR MILES past McMinnville on Highway 18, a couple of ramshackle barns and two rusting silos stand amid wheat and grass that glows golden-green in a setting spring sun. In one of the smaller buildings, Ramsey McPhillips feeds his five bearded Toggenburg goats before locking them up for the night.

“Hello everyone, who’s hungry?” he asks, swinging the stall door open. Bernadette, one of the three babies (alongside Bernardo and Bridgett—next year all the names will begin with “C”), bounds into his arms.

Locking the stall door, McPhillips steps out. To the east, Mount Hood shimmers above the trees. To the west, Coast Range foothills roll gently beneath a cape of vineyards. And to the southwest rises a mountain of garbage that sprawls over 85 acres and towers 135 feet tall.

McPhillips wears his customary flannel, corduroy jacket, and the battered felt Pendleton hat he’s rarely without. (Even in a suit, he has the hat.) His wild, untrimmed mustache looks like a marmot clinging to the bottom of his nose. He’s the fifth generation of the McPhillips family to operate the farm, which turned 150 this year; nevertheless, his life has been far from pastoral. McPhillips, now 54, has wandered widely, working as everything from a Central Park ranger on a horse named Devo to a combination horticulturist/therapist for the COO of the World Bank.

Looming above a nearby stand of Oregon white ash trees that separates his farm from the dump, the Riverbend Landfill is also closing up for the night—the machinery shutting down and the birds, racoons, and coyotes arriving for what McPhillips and neighbors call “the moonlight buffet.” Started as a small mom-and-pop dump in 1982, it has grown into one of the largest man-made structures in the state, owned by North America’s biggest garbage company, Waste Management Inc.

Municipal solid-waste landfills pose a general conundrum in a state that prides itself on its environmental standards and farmland preservation practices. Among other things, dumps are Oregon’s number one source of climate-warming methane emissions. But Riverbend is particularly troublesome, starting with the location: a bend in the Yamhill River that’s in hazardous proximity to the entire region’s water supply. Within three miles—and easy sight and smell—sit 500 family farms that grow everything from apples to wheat to hazelnuts. Within four miles, there are half a dozen vineyards and award-winning wineries, including the area’s oldest, Eyrie Vineyards, and the state’s largest biodynamic vineyard, Momtazi.

“Why do Yamhill County farmers have to host garbage from urban centers forever?” asks McPhillips, pointing out the fact that half the landfill’s garbage comes from the Portland Metro area. “We’re not a wasteland. We’re some of the best farmland in the world.”

Nobody has watched the landfill grow—and fought it—for longer than McPhillips. His great-great-grandfather homesteaded the farm in 1862. His grandfather was the first head of Oregon’s Environmental Quality Commission. Having long dreamed of transforming the farm into a horticultural school, McPhillips originally planned to simply wait out the endless caravans of garbage trucks: the landfill was originally scheduled to close in 2014. But in 2008, Waste Management announced a plan to double Riverbend’s size and extend its life by 30 years.

So he decided to fight.

“Basically, my family has always been a steward of the environment and agriculture in Oregon,” he says. “We’ve been here 150 years and want to be here another 150 years. This is really about whether or not Oregon values old, traditional farming on great soil and clean rivers, or whether it wants to export its garbage to the wine country and destroy farmland.”

What has unfolded since is one of the Willamette Valley’s strangest, longest, and most expensive political battles. McPhillips may have started out as an eccentric Don Quixote NIMBY farmer tilting at landfills, but his efforts have brought together a rare coalition of farmers, environmentalists, land use advocates, and vineyard owners who have fought the landfill’s expansion at the ballot box, in the Yamhill County Commission, and all the way through the Oregon land use system. Yet even as the fertile land surrounding the dump has come to epitomize the national farm-to-table movement and become the toast of international oenophiles, Waste Management has unrelentingly pushed to expand.

Now the battle has entered a new stage. One of the landfill’s early engineers has joined McPhillips’ coalition with allegations and evidence that Riverbend Landfill has violated its permits and is possibly leaking toxins into the water table. Other engineers and scientists believe that an earthquake—even a 7.0 on the Richter scale, a quake much weaker than the 9.0 often forecast for Oregon—could turn Riverbend into an environmental catastrophe. Meanwhile, the $13.4 billion Fortune 500 trash corporation has brought in one of its top troubleshooters to soothe the opposition and unveil a smaller, ostensibly more environmentally friendly expansion—but an expansion nonetheless.

“This is what the country’s going through: corporations versus the small guy,” says McPhillips. “It’s very rare in the history of giant corporations that they don’t get their way. But we still think we have achance. We’re not throwing spaghetti against the wall.”

{page break}

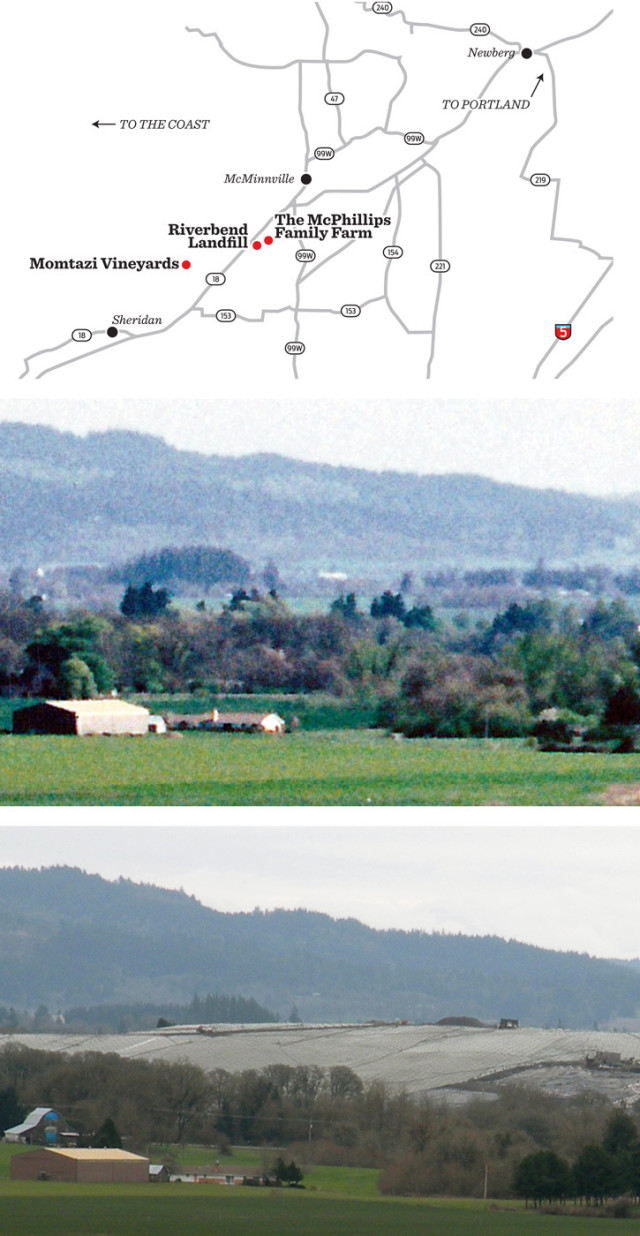

A map of the area and contrasting photos from 1991 (above) and 2012 show the landfill’s incredible growth over 21 years

Image: Courtesy Greg Perezselsky

In 1854, Bernard McPhillips drove a herd of cattle from California to Oregon, eventually becoming a leading farmer in McMinnville. His son started the US Bank of McMinnville and cofounded First Federal Savings and Loan. His grandson, Ramsey’s grandfather, pioneered Oregon’s model environmental system, serving under nine governors as a member of the State Sanitary Authority and then as the first chairman of the Environmental Quality Commission. Among many gifts to the city and state, the family donated its beachfront property—a little stretch now known as Cape Kiwanda State Park.

Ramsey intended to carry the family banner by taking on stewardship of the farm upon his grandfather’s passing. Until then, he hopscotched around the world, living what amounted to a Kerouac novel—from stints as a mounted ranger and performance artist in New York, to cultivating Hollywood celebrities’ gardens as a self-described “hortivangelist,” to amassing an array of big-name art world friends. (Pink Martini bandleader Thomas Lauderdale has organized a number of anti-Riverbend fundraising concerts.) But all his paths, McPhillips says, led back home: “This was just preparation for McMinnville.”

When his grandfather died in 1991, he returned with the intention of starting a horticultural school. Instead, he discovered that the small-town dump next door, run by his grandfather’s friends, had been bought by a national company and was growing into a regional landfill that accepted garbage from the Portland area and coastal towns. The change at Riverbend and other small garbage dumps grew out of a new federal regulation adopted in 1991 known as Subtitle D, which strongly tightened environmental standards and pushed many small landfills to become regional operations in order to afford required upgrades.

A year later, McPhillips’s neighbor, Lillian Frease, spearheaded an anti-landfill ballot initiative to prohibit landfills within 500 feet of a floodway and limit the importation of trash from beyond Yamhill County. It won by a 2-to-1 margin. But the landfill’s owner, Sanifill, and Yamhill County successfully appealed to the courts that the ballot measure violated interstate commerce laws. McPhillips went back on the road, deferring his future school until the landfill’s slated close in 2014.

Waste Management Inc, a publicly traded, Houston-based corporation, acquired Riverbend in 1998, and in 2008 applied to double its footprint from 85 acres to 172 and increase the height of its hill of trash from 140 to well over 250 feet—about the 18-story height of the iconically remodeled Edith Green-Wendell Wyatt Federal Building in downtown Portland. McPhillips and Frease quickly drafted a new initiative (written by incoming Portland city commissioner Steve Novick) to prevent the expansion of Riverbend and, this time, to ban any new landfills within 2,000 feet of a floodplain.

“We eliminated the commerce laws and went back to what won, assuming it would win again,” he recalls. But Waste Management wasn’t Sanifill, and McPhillips and Frease were hardly prepared for the titan they’d just awoken with a spitball.

Waste Management took the two to court four times over the placement of a comma in the initiative. The litigation cut the campaign’s available time to gather several thousand signatures necessary to qualify for the ballot from several months to two weeks, but McPhillips and Frease succeeded. Then Waste Management hired a leading Salem corporate lobbyist, set up a political action committee called Neighbors Against Higher Garbage Bills, and bankrolled a barrage of ads, commercials, and mailers. Among the claims: “local ‘hortivangelist’ Ramsey McPhillips” wanted to shut down Riverbend, which would “significantly increase garbage bills for ... residents and businesses.” Quoting a Willamette Week profile, the mailers portrayed McPhillips as an elite Portland-raised globe-trotter with no link to Yamhill County. A number of people complained to the local paper, the Yamhill Valley News-Register, about so-called “push-polls,” a political tactic that involves calling voters and asking them loaded questions to shape the results. A Linfield College professor told the paper that “he eventually hung up in anger because ‘they clearly were trying to push me to a position that I did not hold.’”

“It was an endless blitz of misinformation that polarized the county so much,” says McMinnville city councilor Kevin Jeffries, recalling that some ads predicted rates would more than double, despite legal limits on increases. “It freaked out businesses, thinking their trash rates were going to go up.”

The initiative went before voters on November 4, 2008—and plummeted to defeat by a 60/40 margin. Waste Management’s PAC raised almost a million dollars (and spent about $6 per voter) for its campaign, according to Oregon’s Elections Division. “Waste Management has the deepest pockets you can imagine,” says Ilsa Perse, a local land use advocate and gallery owner who joined McPhillips to collect signatures. “We don’t have a PR firm messaging for us, and consequently we don’t always do the best job.”

Waste Management, according to Jackie Lang, the company’s communications director for Oregon, saw the “resounding rejection” of the measure as “the kind of majority that sends a strong message.”

But for McPhillips, the loss, however lopsided, signaled the beginnings of a movement. “That initiative beat the bushes,” he says, “and everybody came out.”

{page break}

During moderate flooding this year, the South Yamhill River covered much of McPhillips’s farm (foreground) and lapped against the landfill and its leachate evaporation pond (background).

Image: Courtesy Peter Ovington

In the picturesque postcards and social-media snapshots from the Willamette Valley’s wine country, the Riverbend Landfill rarely makes an appearance. Yet it rises like a fortress next to the coastal thoroughfare of Highway 18, and the mountainous, plastic-covered heap glows brightly in the morning sun. For vintner Moe Momtazi, the landfill has become an equally looming problem on his ledger sheet.

Momtazi Vineyards sprawls across seven foothills just north of Highway 18. On a late spring day, a battalion of wild turkeys parades between the vines. Momtazi, his thinning black hair graying at the temples, pushes a handful of dried stinging nettles, cut from down the hill, into a large tub of simmering water. He’ll inject the resulting tea into the irrigation system for its medicinal and nutritional properties, part of the holistic biodynamic farming practice.

An engineer by training, Momtazi escaped from Iran in 1982, crossing Pakistan on a motorcycle with his wife, eight months pregnant at the time. He eventually settled in the Willamette Valley, where he’s strived, with the help of his three daughters, to create the largest biodynamic vineyard in the state. Momtazi makes his own wine under the label “Maysara,” but sells half of his fruit to other winemakers to make into their respective wines. “We’ve really tried to take care of the land and grow things holistically,” he says of the biodynamic philosophy, which prizes careful cultivation of the natural properties of a given site. “We don’t import any fertilizer or minerals; we make everything here.”

When Waste Management applied to expand the landfill in 2008, the impact on Momtazi’s business was immediate. His biggest fruit customer, Scott Paul Wines, whose contract was worth over $150,000, dumped him explicitly because of Riverbend’s proximity. Other departing customers implied that it was their reason, too.

“We were selling fruit to 32 different wineries, and right now it’s not even 10,” he says. “I have worked on this project since 1997, putting everything—money, time, and pretty much my soul into it. And then for a big company to destroy that dream for you—it was difficult.”

Even though Yamhill County voters spurned the proposed ban on Waste Management’s expansion, McPhillips and Frease’s nascent group attracted support for stopping the dump’s growth that transcended the valley’s normally rigid lines between farmers, vineyard owners, and environmentalists. They renamed their group Waste Not of Yamhill County, and easily rallied Willamette Riverkeeper, the Yamhill County Soil and Water Conservation District, and the Yamhill County Farm Bureau to their coalition.

“It really became an issue when they wanted to expand,” says David Cruickshank, a Farm Bureau board member and former president, as well as a Republican. “The bureau was pretty unanimous against it, because eventually the county is going to be stuck with this puppy and sooner or later, we believe, something negative’s going to happen. Do you want to eat food that’s being irrigated by leachate and all kinds of heavy metals?”

Momtazi and nearly all of the 180 members of the Willamette Valley Wineries Association also joined. As one of the industry’s most respected vintners, Jason Lett, put it at a county hearing, the growing visibility of the landfill undermines the association’s message: “We grow grapes that taste of the ground.”

For all of the near-revolutionary laws Oregon passed in the ’70s to protect farmland, the fight over Riverbend’s expansion quickly turned to political and legal trench warfare. The anti-dump alliance won an early vote from the county planning commission, but hearings before the Yamhill County Commission itself became long and arduous—one lasted 16 straight hours, until 4 a.m. In the end, Waste Management won a 2-0 vote, with the third commissioner abstaining because, she said, her husband worked for the county’s other trash company. (He was soon hired by Waste Management.)

The neighbors appealed to the state’s powerful land use board, and won. Waste Management then filed a court appeal of its own, and lost. Game over? Waste Management pressed on, applying for an interim fix: build an earthen berm out of rock and wires around the landfill’s perimeter so that its edges can rise high as the middle—allowing an additional 2.9 million cubic yards of capacity, or some six more years’ worth of garbage—while it worked with the county on a new expansion plan.

Dump opponents like McPhillips and Frease see the county government going to great lengths to help Waste Management—and point to the $762,000 in fees the county collected from the company in 2011. “Yamhill County is getting money back per ton,” says Frease. “What’s the incentive for people who’re being funded by the dump to put it out of business?”

For Michael Brandt, director of Yamhill County’s planning department for over 20 years, the battles and legal ins and outs are a simple—if lengthy—procedural story. “What we’re talking about is a private business on private property making a private application,” he says. “When you look at it in the whole scope of things, would I have [originally built a landfill here]? No. Does it make sense now? Unfortunately, yeah it does.”

{page break}

Along with his wife and three daughters, Moe Momtazi runs Maysara Winery and Momtazi Vineyards, Oregon’s largest biodynamic vineyard.

Image: William Anthony

At the spring meeting of the Yamhill County Solid Waste Advisory Committee in the basement of the county courthouse, official business turns to complaints. “We’re still getting odor issues, noise, gas,” says Sherrie Mathison, the county’s solid waste coordinator. “We’re getting new complaints about the sign: four phone complaints, all about the word ‘farting.’”

Mathison refers to a 16-foot-long sign McPhillips erected last year in one of his fields alongside Highway 18: “Welcome to Yamhill County’s Farting Landfill Ghetto.”

“All of the property value has dropped, trailers are abandoned—it’s a ghetto,” McPhillips chirps from his seat in the audience. “Why spend money on something that’s being destroyed? I’m not usually a vulgar guy.”

Then the tenor of the afternoon changes as a new Waste Not ally, Leonard Rydell, steps before the committee with his arms full of rolled maps and stapled documents. “I’ve got about 40 years of engineering experience, and I used to be the engineer of record at Riverbend,” he says as he spreads out the original plans for the landfill and the dyke shielding it from the floodway. Rydell quit in 1985, he says, because the landfill’s original owners consistently refused to follow his plans or the environmental specifications to prevent leakage.

Rydell stayed silent for the next 27 years out of respect for client confidentiality, he says. He’s also a self-avowed small-government Republican who’s never been keen on landfill opponents or the restrictive Oregon land use system. But in November of last year, when Waste Management proposed its stopgap earthen berm, Rydell had to speak up.

“We don’t build a big corral and fill it full of garbage,” says Rydell. “Most landfills are not in a floodway. What happens when the wires rust out and the walls fall down? I thought to myself, this is ridiculous. I’ve kept quiet too long.”

So he spent the next three weeks poring over his original documents and comparing them to the current maps. A licensed pilot, he flew over the landfill and took photos to compare its current activities to its permitted ones. Things were amiss: Waste Management, he believes, has been building over property and zoning lines, digging dirt out of the river’s floodway to cover the garbage each night without proper permitting, and failing to comply with numerous other permitting conditions.

“What’s out there now was never anticipated,” Rydell tells the committee, his voice growing more excited as he delivers his final blow: spreadsheets from DEQ (finally acquired by McPhillips after four years of requests) showing that monitoring wells around the landfill reveal toxic compounds. In short: the landfill is leaking.

In response, Jennifer Redmond-Noble, an advisory committee member representing the landfill’s neighbors, insists they need to hear from a neutral party, like the Army Corps of Engineers. “The real story is the county is doing nothing,” she says sternly, shortly before the meeting adjourns with no plans for further action.

Since that meeting, other experts have joined Rydell in opposing the landfill’s growth. Richard McJunkin, a professional hydrogeologist who’s worked on over 150 hazardous waste sites, says, “I’m not an arm-waving environmentalist who wants everything shut down. We need landfills. But you wouldn’t want to live downgradient from this site. What you can’t see, touch, or smell could very much hurt you.”

Most alarming to McJunkin and others is the prospect of an earthquake. “This puppy is going to liquefy,” he says. “And from my interpretation, it’s going to be the largest environmental disaster in the history of Oregon.”

Yamhill County’s planning department and representatives of Waste Management flatly state that the landfill is in accord with all permits and environmental regulations. “Rydell and the landfill’s opponents are taking snapshots of information at moments in time, and they’re not looking at everything,” says Brandt, in the planning office.

But Waste Not hopes the new information will force state regulators to reject both plans for an earthen wall and larger expansions. “We basically kept them at bay for four years, which no one thought we’d be able to do,” says McPhillips. “Now we have to fire our last guns and hope there’s some smoke.”

{page break}

Paul Burns, Waste Managment’s Pacific Northwest director of disposal operations, stands in the landfill’s grove of poplars.

Image: William Anthony

In the thick of its battles with angry farmers and environmentalists, Waste Management brought in its own expert: Paul Burns, a 54-year-old engineer who has worked for the company for 23 years, smoothing over political controversies surrounding landfills from Maine to Hawaii. Burns arrived on the Yamhill scene in 2009. Members of the anti-dump coalition say that he’s freely told them that Waste Management sends him to solve its problems. “I used to think of myself as an engineer,” says the ever amiable Burns, “but now I’m a teacher.”

One summer day, Burns offers a tour of the grove of poplars that partly screens Riverbend Landfill from Highway 18. Standing between rows of trees as straight as church columns, Burns explains that the thin black tubes running through the undergrowth irrigate the roots with diluted leachate—the potentially toxic stew created from rain and other liquids that seep through the landfill’s decomposing matter and pool at the bottom—the stuff opponents fear is leaking. But in the grove, which won an award from the American Academy of Environmental Engineers, the tree roots absorb the leachate before it enters the water table. The company then periodically harvests the trees to sell for pulp.

Burns points to this green-design element as evidence of fundamental goodwill.

“I’ve worked on controversial sites before, and the key is communication,” Burns says. “We want to hear what people are saying, change what we can change, and be the best neighbors we can be.”

Beginning earlier this year, Waste Management has held monthly community meetings to give presentations and discuss topics one by one with its hired experts, from water quality and the well-monitoring system to whether the landfill is in the South Yamhill River floodway. And the company, Burns points out, is making concessions, starting with the announcement at a May community meeting that Riverbend would no longer seek an additional 10 feet of height. To McPhillips’s “Thank you,” Burns gave his customary response: “We listen.”

“Paul’s done an amazing job of communication,” McPhillips acknowledges. “The way he’s treated the community has been far more respectful. We really appreciate that they’ve come to the table to inform us what they’re doing, but it’s only furthered our resolve that what they’re doing is not good for the community.”

Each meeting between Waste Management and its opponents is a tensely cordial affair: shared pizza, the occasional release valve of humor. “There is a long way to go with several important Riverbend issues,” says hydrogeologist McJunkin, who tends to be the most aggressive in his technical challenges of Waste Management’s experts. “Waste Management will send as many Ph.D.’s as needed to attack the issues being raised.”

For his part, Burns sees the future of trash in more technology and recycling. In North Portland, he notes, Waste Management is building the first commercial-scale plant devoted to a new process: turning hard-to-recycle and contaminated plastics into synthetic fuels. He points to a site he worked on in Rochester, New Hampshire, as his example for Riverbend: substantial community involvement that produced a landfill replete with parks, wetlands, and even a golf course, plus a gas-to-energy plant.

“Long-term expansion is still where we plan to go,” Burns says flatly of the mountain of trash in Oregon’s farm and wine country. “But it won’t be the expansion everyone saw before, where the idea was to fit as much as we can.”

Meanwhile, the dump’s opponents have convinced state regulators to take a closer look at floodway and seismic issues. DEQ permit engineer Bob Schwarz has asked Waste Management for further data to prove that the landfill is not in the floodway and is not on soil that might liquefy in an earthquake. “If those things can be addressed satisfactorily,” he says, “I don’t believe the regulations regarding a landfill would allow us to prevent it from expanding.”

McPhillips has taken down his “farting landfill” sign. He’s moved into the 1860s caretaker’s house right next to the dump, renting out the family farmhouse to pay legal bills arising from his fight. And he vows to keep fighting.

“My grandfather worked harder than anyone in this state to fight for clean rivers and air,” McPhillips says. “On his deathbed, he told me, ‘Nothing great is ever achieved without Uncle Controversy in control.’ I’m not going to let this be the final chapter in the McPhillips story.”