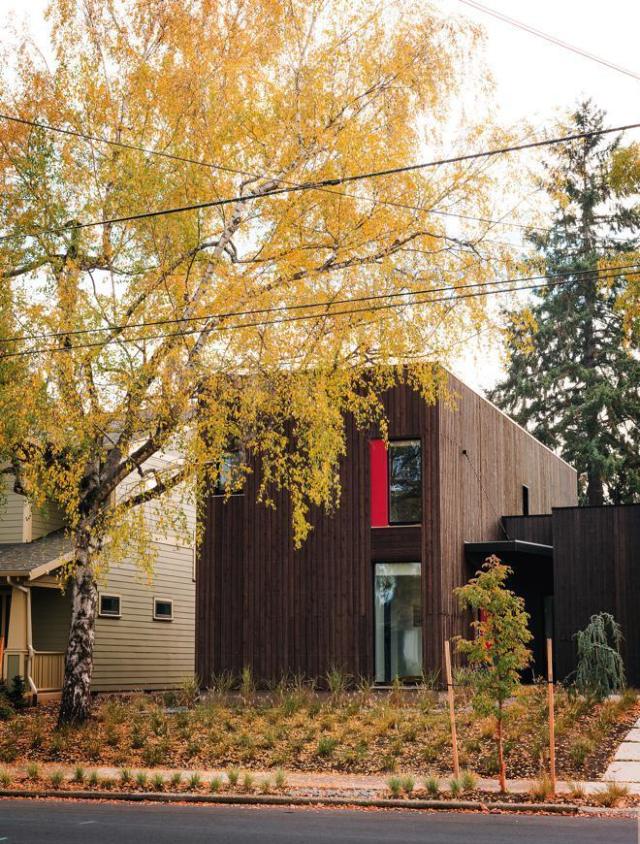

An Eco-Chic Passive House

The home is a study in clean design, from the folded-steel stairs to the midcentury furniture to the exterior (below), scaled to echo the adjacent houses without mimicking them.

Image: Bruce Wolf

Artist Karen Thurman imagines that in a past life she was “probably a lizard.” Even in a room where others are overheating, she is often chilly. “I’m only really happy,” she says, “when it’s really hot.”

Image: Bruce Wolf

Her husband, architect Jeff Stern, has worked for top Portland firms, helping to pioneer bold, complicated, and often expensive new systems for energy efficiency in large buildings. So when Stern set out to design a house for himself, four conflicting goals tugged on his ambitions: simple design, low energy consumption, affordability, and comfort.

On his larger projects, Stern routinely relied on mechanical engineers’ elaborate computer models to predict how technologies like radiant heating and natural ventilation would perform. But for his own home, Stern turned to a simpler blend of low-tech and high-performance building used in Europe for two decades but only now making inroads in the US: “Passive House.” The basic idea, according to Ryan Shanahan of Earth Advantage, a Portland-based sustainable building consultancy, is to design a house that is “like a thermos,” with the air warmed by both the sun and the occupants, and cooled only by opening the lid.

“I realize now,” Stern says, looking back at his more complicated designs, “it’s just a matter of simple physics.”

Since their spring move-in, Stern and Thurman’s Northeast Portland house has “stayed a steady 70 degrees.” Last summer’s warmest days required only opening the windows. “Visitors thought we had air conditioning,” Stern says. So far this winter, they’ve rarely turned on the four small convection heaters standing at the ready for Portland’s occasional cold snaps.

The techniques behind the Passive House concept have been around since the 1970s. But in the mid-’90s, researcher Wolfgang Feist in Darmstadt, Germany, developed official standards and promoted them through his Passivhaus Institute. Feist also developed software for calculating the efficiencies of insulation, window sizes, renewable energy production, and other features, all easily adjusted for any climate. (Soon, Passivhaus plans to release 3-D modeling software.) Today more than 15,000 buildings have earned the institute’s rating, most of them houses, but also hotels in the Alps and a 20-story office tower in Vienna. Architect Katrin Klingenberg completed the first Passivhaus-rated home in the US in Illinois in 2006, and a year later cofounded the Passive House Institute US, which held its annual conference in Portland in 2010. According to Shanahan, about 12 Passive House–rated buildings have been completed in the Portland area, with eight more under way, ranging from a retrofitted 1990s house in Southeast to a 57-unit apartment complex called “The Orchards” in Orenco by Reach Community Development, slated to be built in 2014.

Alameda Metalworks crafted the prominent, folded-steel stairway.

Image: Bruce Wolf

Stern estimates that his home, with its 4.32 kW solar array, will be near “net-zero” in its draw from the power grid. But beyond energy savings, the simple, physics-driven technology helped him to evolve an equally elegant simplicity in the design. “With Passive House Planning Package software, I can do the energy modeling myself,” he says. “So it allowed me to ask, ‘Well, what if I put a window here? Or make this one smaller, or add insulation here?’ I got instant feedback. I could really tune the design.”

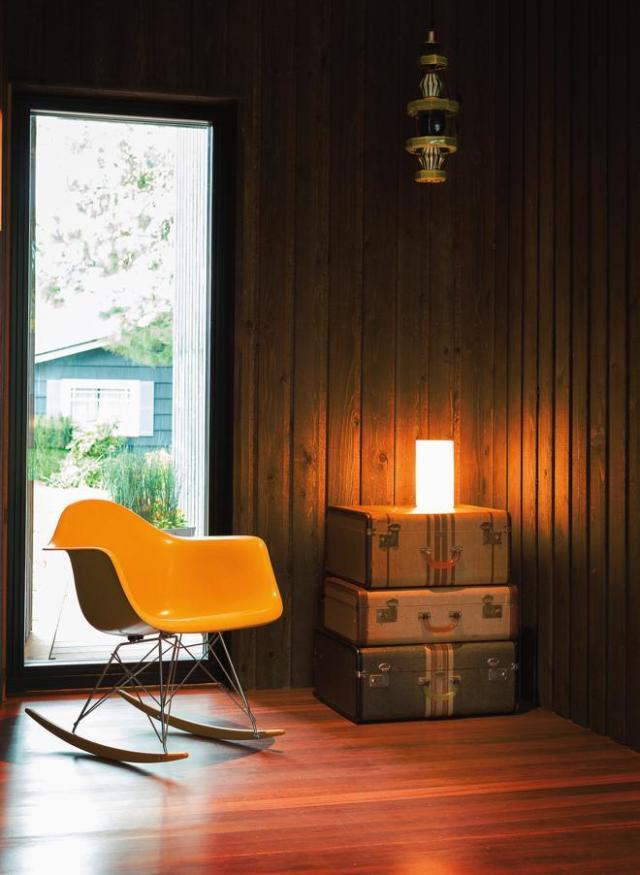

An Eames rocker and vintage suitcases anchor the breezeway.

Image: Bruce Wolf

Indeed, the environs are a seemingly effortless architectural melody of light and space. The house features a low-ceilinged entry and breezeway that opens into two wings—one for living, one for work. The living room expands with a soaring, 17-foot-tall ceiling and two south-facing windows (one a sliding glass door) that, together, shape a 15-by-11-foot expanse of glass quickly covered by elegant, motor-operated Hella exterior shades when “solar gain” becomes overwhelming. There are only 10 other windows, mostly small, in the rest of the house. A mezzanine contains the bedroom, bathroom, and an 80-square-foot closet. (In a home that otherwise expresses the couple’s minimalist lifestyle, Thurman concedes that clothes are “my weakest point of self-control.”) The workspace wing has two rooms: Stern’s cozy office and Thurman’s studio, where windows overlook a backyard garden and bathe her in southern light (and warmth) as she crafts her celebrated colorful felt scarves, sweaters, pillowcases, and table runners.

Early on, the couple focused their splurges: wood-framed windows (which, in the high-performance, triple-glazed variety Passive House standards demand, could be found only in Poland, shipped with a princely customs surcharge) and a raw steel stairway to the second floor. Even on the less precious elements, nothing went to waste: Stern designed nightstands from scraps of the inexpensive plywood cabinets and plastic laminate countertops.

Thurman’s art studio features warming southern light, copious storage, and an ideal space in which to enjoy her chosen background noise: Turner Classic Movies.

Image: Bruce Wolf

With décor largely comprising modernist classics—George Nelson clock, Modernica dining table, Emeco Norman Foster stools, Heywood Wakefield table—the home isn’t lacking in stylish, design-savvy accoutrements.

And it is uncannily comfortable, fed by another Passive House standard: a high-efficiency heat exchange ventilator that propels one full interchange of fresh air every three hours (see “Passive Principles,” below).

Stern, who now has his own small practice and is a certified Passive House consultant, shakes his head at the complexity of the sustainable buildings he once designed. Meantime, Thurman’s lizard-like yearnings are satisfied, both for warmth and for peace. “The house is so quiet,” she says of an unexpected benefit of the tight insulation. “We barely hear the outside world at all.”

Passive Principles

Earth Advantage consultant Ryan Shanahan outlines the tenets of Passive House design.

←Insulation Oregon’s energy codes typically require six inches of insulation. Passive House pushes designers to use twice that—not just in a building’s walls, but beneath the floors and roof. Windows must be triple-paned with high-performance glass, with insulation even in the frames.

Seals→ Shanahan likens the design to “adding a rain shell over a sweater on a windy day.” Because most buildings lose 30 percent of their energy through leaks, the “envelopes” must be sealed tight. Instead of sliding windows, Passive House designs often feature tilt-and-turn windows with three different locks to assure a tight seal.

A recirculating range hood assures venting won’t break the tight Passive House seal.

Image: Bruce Wolf

Air Exchange All Passive House designs feature a heat recovery ventilator, which trades stale air for fresh air while recycling the energy typically lost in the transfer. Not only does this create a comfortable environment, it reduces dust and allergens while preventing the kind of condensation that can cause mold or rot in wood-framed construction. (Homeowners can hit a booster switch to propel the circulating air if they choose.)

Cost A first-time builder trying Passive House standards might spend 20 percent more over conventional construction. Experienced builders who have already strived to exceed energy codes on projects through other means can see as little as a 5 percent increase.

For more information, visit Earth Advantage, Passivhaus Institute, or Passive House Institute US.

A tin horse and bird sculptures from Dou Dou Studio contrast with the home’s minimalist aesthetic.

Image: Bruce Wolf