To Save or Not to Save: Is the Portland Building Better in Person or the Pictures?

Like a civic version of dyspepsia, the perennial debate over the fate of Portland’s most famous work of architecture—the Portland Building—is gurgling again.

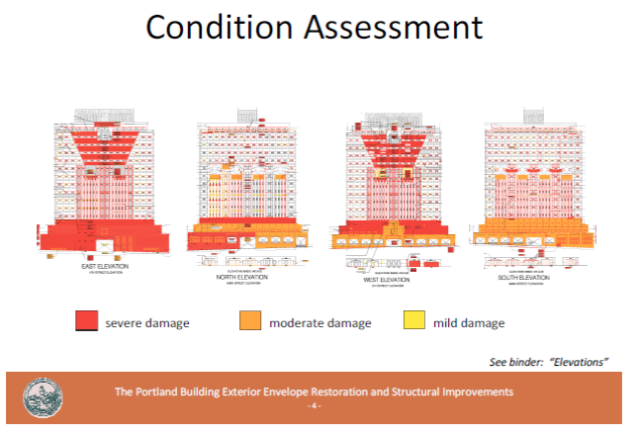

Sixteen years after the city spent $9 million to fix the 1982 postmodernist icon’s sagging 14th and 15th floor, it’s now facing a $95-million top-to-bottom overhaul because virtually every joint in the building is leaking. But as haters of the building call for its demolition and preservationists wail to save it, I’d like to pose a simple question that ought to be asked before spending millions of dollars to save any historic building: is the real thing better than the pictures?

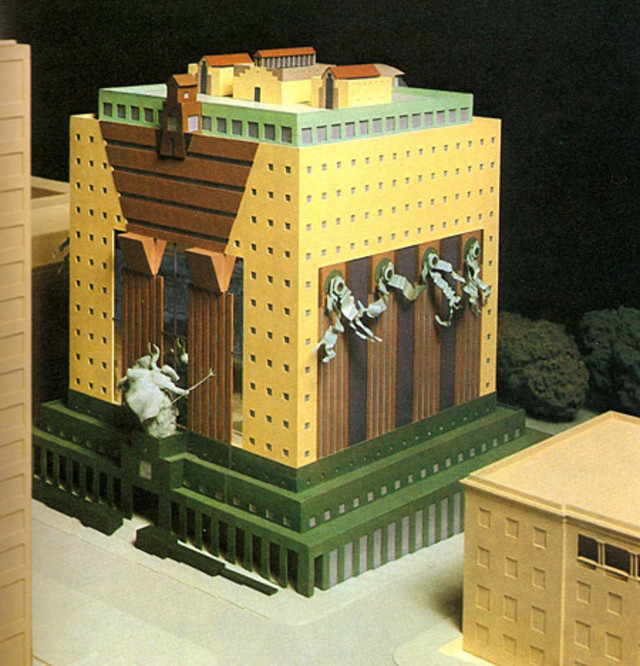

For sure, the real thing has its problems. Completed in 1982 in for $51/square foot—less than a decent house would have cost to build at the time—it stands as a living, leaking monument to what the late historian E. Kimbark MacColl liked to quip was Portland’s habit of expecting “first-class passage on a steerage ticket.” Then-mayor Frank Ivancie wanted an architectural landmark for his new city office building, so he hired famed architect/tastemaker Philip Johnson to get him one. Johnson set up a design competition, but wired the point system to favor the architect he wanted to win—Michael Graves—by offering what Ivancie and his cronies wanted even more than an icon: the largest, cheapest building possible. In his mid-40s, with scarcely a built project to his name, Graves beat out far more experienced architects like Arthur Erickson and Mitchell-Giurgolaon on cost alone.

Click to see the Portland Building's condition assessment

The city even pioneered an entirely new, cheaper way of constructing the building: “design/build,” a fast-track technique that puts the contractor in the lead role with the architect and engineers as subcontractors. Surprise: there were glitches, from the structural problems that plagued the building in the mid-‘90s years ago (It didn’t even meet the seismic codes of its day) to an undersized heating and ventilation system to the leaky seals that now plague nearly every window and tile.

Yet the construction problems are only one part of the Portland Building’s sadness. Graves’ original, garland-festooned confection was value-engineered to a graphic study of color and pattern. The interior is a miserable place to work: the tiny windows yield little natural light (Johnson’s Arab-Oil-Embargo-era competition prized energy efficiency which, with the technology of the time, was a building with no windows.) And then there’s the building’s urban design: city officials wanted the main entrance to face the then-new transit mall, but ironically, still wanted parking in the building for themselves—thus, a cavernous garage door faces a city park. As one architecture critic wryly put it: “Where you expect dignity, you get the building's anus.”

But does all of this add up to an argument for tearing the building down?

My guess is the numbers will save it. (Burrow into the city’s cost estimates, and the actual renovation runs $30 million in hard construction costs; a new building could easily run three times that). For enviros calling for a new, uber-eco building, most credible sustainability advocates will rightly point out that, in terms of embodied energy and environmental impact, the greenest the building is the one that’s already there. And then there’s habit: Portland has a long record of spending millions on buildings that were far more lost causes than the Portland Building (Wieden & Kennedy’s and Ecotrusts rehabs of old paint warehouses, Portland Center Stage’s redo of an ancient armory, the city’s and county’s redos of Portland City Hall and Multnomah County Library.)

The original model of the Portland Building

But, that aside, let’s ask, Does the Portland Building deserve to live on its architectural and historical merits alone? Does actually seeing and experiencing the building matter?

One the one hand, no. There are many, far more successful landmarks postmodernism, several of them by Graves (the San Juan de Capistrano Library in Puerto Rico or the Humana Building in Atlanta, for instance). For the historical record, photos of the Portland Building could be just fine.

But there are two good reasons why we should save it. The first stands mere steps away in the form of the Commonwealth Building, a 1948 modernist masterpiece by Pietro Belluschi. One of the first two aluminum-and-glass curtain-wall buildings in the world—and an uncommonly beautiful version of the genre—it ushered in the very era of otherwise drab, monochromatic buildings that Philip Johnson and Michael Graves wanted architecture to break free of. However much a lesser of work of architecture the Portland Building is, it gives one city—Portland—the bookends to a historic era.

The second reason has nothing to do with history, but everything to do with our experience of the city: color. Drive into downtown over one of our bridges or scan the skyline from the West Hills, and out of the collage of white, grays, and blacks of the architecture and the greens of the trees, only three buildings stand out—the US Bancorp Tower, 1000 Broadway, and the Portland Building—two because they’re big and pink, the other because it’s a pattern of salmon, blue, and beige. Do we really want to lose that?