The Road to Legal Gay Marriage in Oregon

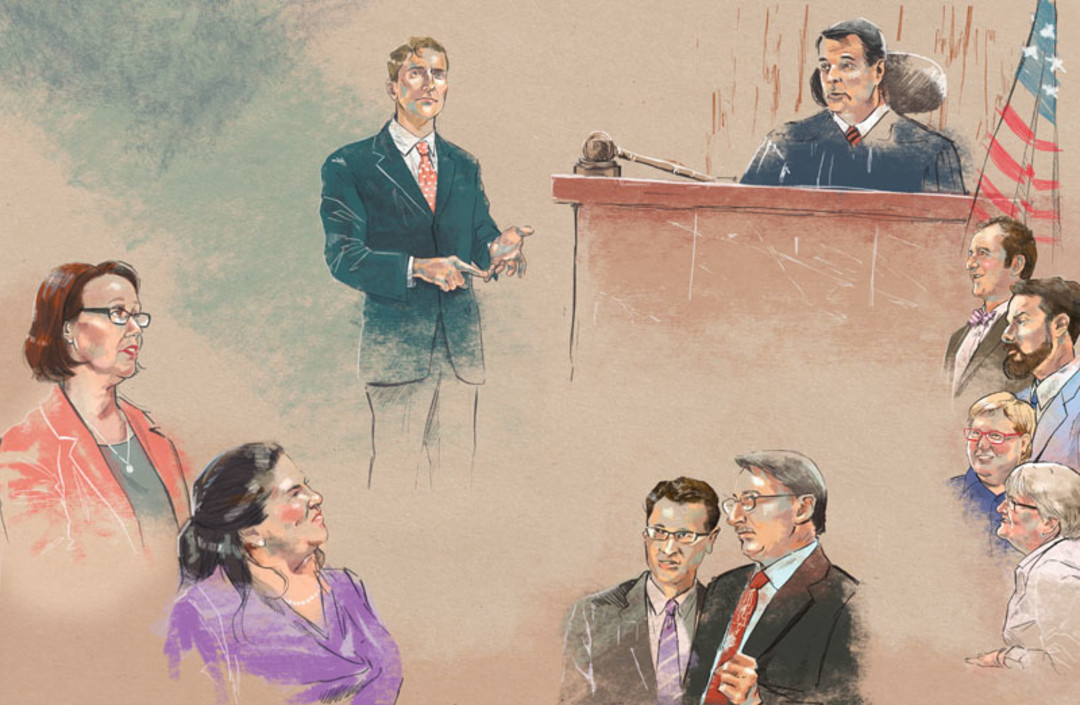

Counterclockwise from Top Left: Lake Perriguey, Ellen Rosenblum, Jeana Frazzini, Misha Isaak, David Fidanque, Deanna Geiger, Janine Nelson, Paul Rummell, Benjamin West, Judge Michael McShane

When a federal judge ruled Oregon’s same-sex-marriage ban unconstitutional in May, the decision sparked jubilation, but also a few shrugs: with gay marriage already legal in states like Iowa and New Mexico, and bans teetering in the likes of Idaho and Arkansas, Oregon seemed a foregone conclusion. The truth is, Michael McShane’s decision might never have happened if not for two rogue attorneys who bucked the gay political establishment, setting in motion an unusual legal battle in which everyone was on the same side (with one frustrated exception).

1. Lake Perriguey

Citing the Constitution’s principle of equal protection, the US Supreme Court ruled last summer that the national government must recognize same-sex marriages from states where such unions are legal, igniting a brush fire of court cases in states where they weren’t. Perriguey, an outspoken Portland attorney with a track record of representing LGBT clients in discrimination suits, filed a federal lawsuit on behalf of two same-sex couples in October, along with fellow local lawyer Lea Ann Easton. Basic Rights Oregon (BRO), the state’s leading gay-rights organization, was gearing up for a campaign to qualify a marriage-equality initiative for the ballot, but Perriguey’s clients didn’t think an expensive and potentially vitriolic ballot fight was the best path. “The notion that gay people’s rights are subject to a popularity contest is outrageous,” says Perriguey.

2. Ellen Rosenblum

As soon as Perriguey launched his offensive, the state’s Democratic attorney general essentially waved a white flag. The day after he filed suit, Rosenblum directed state agencies to recognize same-sex marriages performed outside Oregon. Then, in February, she announced she wouldn’t defend the state’s ban, writing that it “cannot withstand a federal constitutional challenge.” At the key April hearing in the case, attorneys from Rosenblum’s office argued that they couldn’t mount a defense consistent with Oregon’s eloquent domestic-partnership statutes, which declare the state’s “strong interest in promoting stable and lasting families, including the families of same-sex couples.”

3. Jeana Frazzini

The executive director of BRO since 2008, Frazzini had overseen the powerful group’s long-game marriage-equality strategy: years of painstaking outreach to sway public opinion, planned to culminate in a 2014 initiative. After the Supreme Court’s decision, the organization weighed a parallel legal strategy. But when Perriguey brought his challenge, BRO found its own plaintiffs and filed a case in December with a motion to consolidate—against the wishes of Perriguey’s clients. “Litigation was happening,” Frazzini says, “whether or not the timing or approach was how we would have approached it.”

4. Judge Michael McShane

McShane had been a federal judge for only a few months when the case landed in his court—made all the more visible by the fact that he is one of only nine openly gay members of the federal judiciary. Some argued he might be a beneficiary of the case and therefore unfit to rule—among them, National Organization for Marriage Chairman John Eastman, who sought belatedly to intervene. (As of press time, NOM had until August 25 to argue that it has standing to appeal the case.) McShane tackled his sexuality head-on, both in court—pointing out that he had as much in common with Eastman (age, race, field of law) as with the plaintiffs—and in his uncommonly personal ruling, in which he recalls growing up in a time when homosexuality was considered immoral and peers played “smear the queer.” “It is not surprising then that many of us raised with such a world view would wish to protect our beliefs,” McShane writes. But, he continues, “I believe that if we can look for a moment past gender and sexuality, we can see in these plaintiffs nothing more or less than our own families.” (Interestingly, McShane almost exclusively uses the term “same-gender marriage” instead of “same-sex,” a thus far nationally unique distinction that possibly includes transgender people in the decision, says Perriguey.)

5. David Fidanque

Oregon’s ACLU chapter, under Fidanque’s direction, contributed flame-forged experience and legal talent. At the April hearing, ACLU/BRO counsel Misha Isaak—who celebrated his 10-year anniversary with his husband the same week McShane issued his decision—performed so formidably that, at times, McShane’s questioning felt like the judge was soliciting advice from Isaak on how to structure a ruling that would withstand any future appeals.

6. The Plaintiffs

The original case included Robert Duehmig and William Griesar, who married in Canada in 2003 and are the fathers of a pair of teens, and Janine Nelson and Deanna Geiger, who became the first same-sex couple to marry in Oregon following McShane’s decision. They have been together for more than three decades. Paul Rummell (top right), an air force vet, and Benjamin West, a nursing student, met at Portland Pride eight years ago and recently adopted an 8-year-old boy. Lisa Chickadonz and Chris Tanner have been engaged for 29 years and have two grown kids.