The Mad Science Behind OMSI's Greatest Exhibits

Image: OMSI

On a summer day at OMSI, children and parents explore Roots of Wisdom, a new exhibit in the museum’s Earth Hall. The 2,000- square-foot display, funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation, examines how centuries-old Native American knowledge remains relevant. Kids try their hands at basket weaving, while adults marvel that everything from chewing gum to aspirin traces back to indigenous know-how.

One kiosk invites visitors to consider the importance of river cane to a healthy watershed. Inside a glass box, two opposing surfaces slope down toward a trough, representing a river and its banks. One “bank” is adorned with miniature river cane; the other is bare. A visitor turns a crank on the mechanism’s side, causing plastic balls representing water to “flow” down both banks.

Holes perforate each of the model’s banks. On the side with river cane, the balls move slowly, frequently dropping through the holes to mimic the absorption of real water into soil. On the bare side, balls roll quickly to the “river.” Visitors instantly see how river cane reduces runoff and erosion.

If you (with or without your kids, nieces, nephews, or protégés) visit a major American science museum, you’re likely to see work like this—perhaps a display demonstrating special effects on TV shows in Dexter’s Laboratory, or a series of logic games and brain teasers called Mindbender Mansion—that was designed and built at OMSI’s Central Eastside campus. The museum’s team of about 40 writers, engineers, programmers, 2- and 3-D designers, and builders constitutes one of the country’s most prolific exhibition design and building programs.

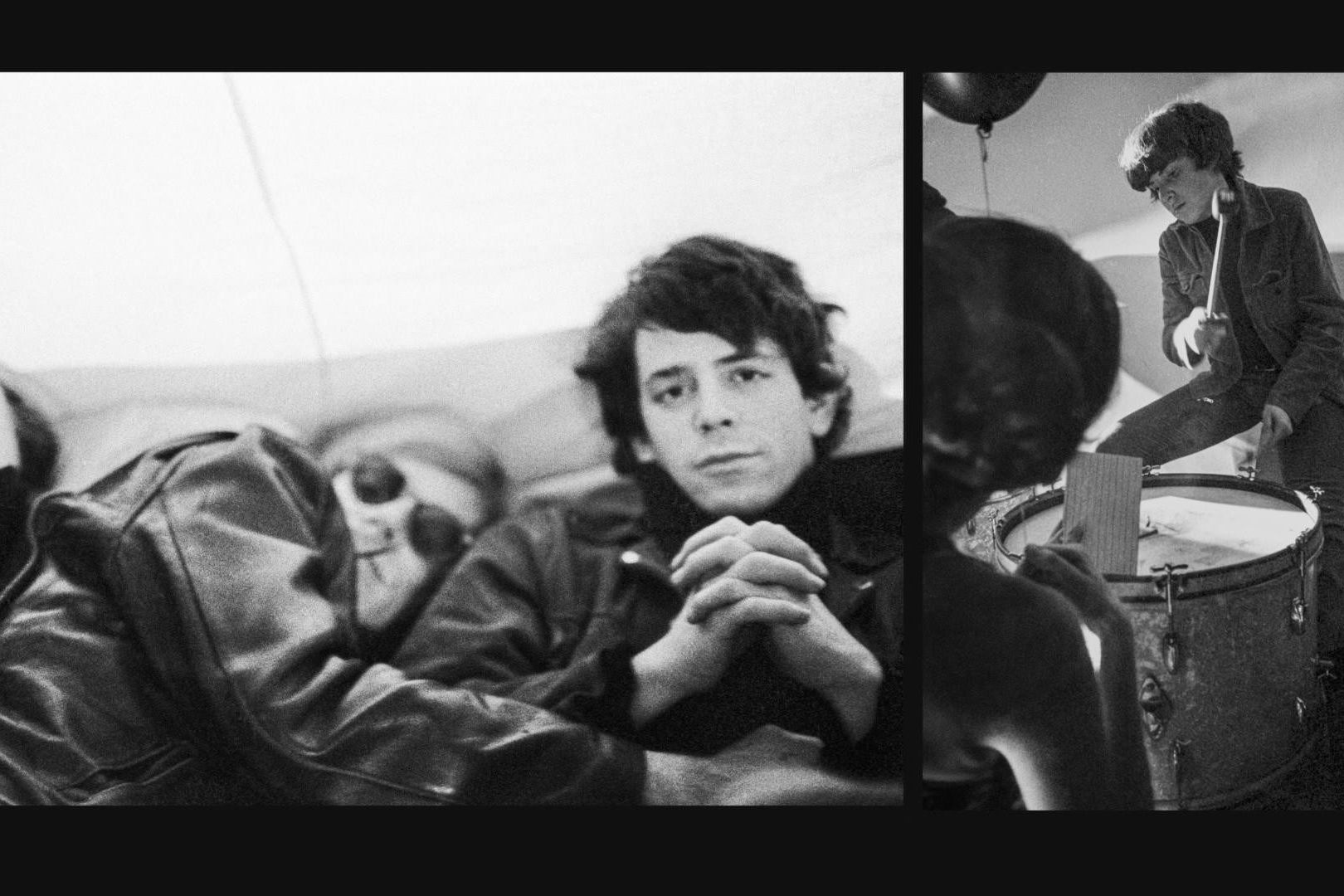

OMSI designers (from left) Cecilia Nguyen, Kate Sams, Kari Jensen, Kevin Kearns, Todd Kehoe, Jaclyn Barber, Ivel Gontan, Matt Reineck, Kirby Jones, and Owen Premore

Image: William Anthony

With this team, OMSI creates major touring shows and smaller permanent installations for museums around the country, all of which can be packed up, shipped, and reassembled. Some shows stay on the road for more than a decade, as OMSI teaches America’s youth some odd and interesting things. Animation, a 6,000-square-foot collaboration with Cartoon Network, explores the math, science, and history behind popular cartoons. Visitors experiment with early tools like a pantograph—a simple mechanism used to trace and transfer images—but also interactive, digital animation tools. The show has toured in great demand since it debuted at OMSI in 2005. A View from Space, a smaller, bilingual exhibit produced in collaboration with NASA, offers kids the chance to track hurricanes and simulate launching a satellite into orbit.

OMSI's Animal Secrets

Image: OMSI

While seldom considered among the mass media, successful science-museum exhibits reach huge audiences. The International Exhibition of Sherlock Holmes, for example, drew about 70,000 visitors during its world-premiere run at OMSI last fall, and is booked through the next two years at museums around the country. The field of exhibition design is dominated by for-profit companies, whose work tends to emphasize visual stimulation, sometimes, an observer could argue, at education’s expense. Dinosaurs Unearthed, created by a private Canadian company of the same name, lures viewers with moving dinosaur models but few hands-on learning activities. Not many museums compete at this scale; the Exploratorium in San Francisco, for example, employs an exhibit design staff about half the size of OMSI’s.

The 26,000-square-foot workshop at OMSI bears the marks of the untidy side of the creative process: scattered wood scraps and worn blueprints cover the surfaces, a line of screeching table saws and other woodworking tools flank one side of the room. A scrim of sawdust carpets the floor, while relics from past exhibits adorn the walls; rejects and mock-ups from Animation peek out from behind pipes.

OMSI's submarine

Image: OMSI

During my visit, the primary focus is on the shop’s next big traveling exhibition, an NSF-funded exploration of the human microbiome called The Zoo in You. Components lie around in various states of completion, some half-painted with protruding wiring, others still an unrecognizable amalgam of wood and nails.

Todd Kehoe, the production manager, hands me the blueprint for a display called “Baby’s First Microbes,” intended to demonstrate how infants acquire microorganisms. At the moment, the sketch looks like the skeleton of a wooden table. But the finished product will be mounted with handles, allowing visitors to roll a large metal ball around the table’s surface and over various targets representing events in an infant’s life. “The ball will pass over a magnetic sensor that’s buried under the targets, and as it passes it will light up a little ring of LEDs,” Kehoe explains. The plan suggests a much larger version of the little wristwatch games that used to come in McDonald’s Happy Meals: hit all the targets, collect all the microbes. Kids will love it.

OMSI's Earth Hall

Image: OMSI

Museums across the country trust OMSI’s work. “They design a great show that travels well and provides our guests with a cool hands-on experience,” says Josh Kessler of Columbus, Ohio’s Center of Science and Industry, where many OMSI exhibits have appeared. To reach distant crowds, exhibits must be both easily transportable and durable enough for life on the road. Assembly and disassembly must be possible with minimal remote support. “The design challenge is to make sure the exhibits don’t look like they’re made to fit on carts,” Kehoe jokes. But communicating the educational message in a way that visitors will retain is still the priority.

This is where OMSI excels: creating the visual and tactile excitement to grab visitors, along with the intellectual depth to actually teach them something. It’s what Kevin Kerns, vice president of exhibits, calls “free-choice learning,” a crucial design challenge for the organization. “We don’t get to force you to sit down and listen to us,” he says.

OMSI's Renewable Energy Exhibit

Image: OMSI

Out on OMSI’s floor, a mother and daughter turn the cranks on the river-cane simulation, watching the balls roll through the cane and counting the few that make it all the way to the river. An older girl sits at the basket-weaving station, brow furrowed, trying to emulate the patterns on display with the cloth strands provided for visitors to try their hand at the ancient Native American craft. A video of salmon sizzling on skewers draws visitors to a section of the exhibit about traditional fishing practices.

Looking on, Kehoe notices room for improvement. At the river-cane exhibit, the trough in which the balls fall is too high, obscuring the view for shorter children. The crank returns balls to the top too slowly; the gear ratio needs to be higher to ensure no one gets bored. He makes mental notes that will lead to an on-the-fly revision of this particular display. “Even though it’s been sitting in the shop for a couple months being built, you’re going to miss these kind of things,” he says.

OMSI itself is making a larger adjustment. The museum hopes to direct its expertise beyond its own walls, including addressing challenges faced by Portland and other cities, turning its riverside headquarters into a teaching laboratory on urban infrastructure. A materials lab housed in the exhibit-design workshop already hosts students and researchers from Portland State University, who design welds and alloys for complex structures like bridges.

Kearns gestures toward a small exhibit in the back as he walks into Turbine Hall, the museum’s bright, echoing expanse of displays named after the retired steam turbine dating to the building’s early days as a PGE plant. It’s a simple mechanism one might find in any science museum: a round, metal surface with a slowly steepening grade toward the center, where it drops off entirely into a hole. Kids roll balls around and around, watching as they slowly circle the hole in the center, illustrating planetary orbits and gravity.

Kearns envisions it as something else entirely. “This could help explore aspects of transportation,” he says. “There could be rubber balls, metal balls, and wood balls. It could look at why railroads are effective, [comparing] metal, which has the lowest friction, versus rubber, which has the highest friction.”

It’s this attention to both the detail and the greater scheme—ensuring that every component contributes to the big picture—that puts this exhibit team on the map. By playing to its own strength in this esoteric aspect of design, OMSI hopes to help shape change in the wider world.