Is This the Best Way to Educate Children with Autism?

Students from Victory Academy’s “Sellwood” class await a bus for a field trip: Bailey (from left), Faith, Jamie, Shane, and instructor Molly Smith.

Image: Leah Nash

Miles Pollock has the round, welcoming face of a young Benjamin Franklin. His eyes shine over glasses that often slip to the tip of his nose. On a cloudy May morning at Victory Academy, Oregon’s only year-round school for autistic kids, the 11-year-old works to master three phonetic sounds: the “cuh” of car, the “luh” of yellow, and the “yuh” of you.

After a few drills, Victory speech therapist Anna Cox invites Miles to test-drive his partially mastered “luh” in a full sentence. Miles meets her encouragement (“Won’t it be fun!”) with a dryly adult chuckle: “Heh. Heh. Heh.”

Victory Academy student Miles Pollack

Image: Leah Nash

“Say it slowly, Miles: ‘I ... love ... you.’”

“I... luh-uv... yuh,” he attempts, stalling.

Then: “I... luh-uhv... yyyyuhh,” he says, momentum building.

And then: “I luh-uhv YOOOO!” he says, rising out of his chair. “I luh-uhv YOO!”

“That was awesome,” Cox says, clapping.

“Phee-uew!” Miles gusts with the relief of a driver who’s just narrowly steered clear of a car wreck.

A year before, Miles’s inability to communicate simple things could lead to fits of screaming, or to blank resignation. Often lost in an inner world, he would stroll ahead of his teachers and, unless they intervened, blithely wander into busy streets. He scorned typing, a tool often deployed to help those with autism communicate. But thanks to Victory’s regimen of lessons, therapies, cheers, and hugs, Miles now marks many successes, ranging from mastering an expression of affection to the now-routine three- and four-sentence e-mails he sends to his mom, recounting the lessons of the day.

After discovering Miles’s autism when he was 18 months old, his parents immersed him in a cycle of rigorous behavioral therapies. A team of five or six therapists rotated in two-hour shifts, seven days a week. The family installed a two-way mirror so that therapists and parents could observe one another and share feedback during weekly meetings. Yet Miles didn’t start talking until he was 4 years old. By the time he entered Victory Academy at age 7, his utterances could only rarely be understood. His independence stretched little beyond going to the bathroom alone.

“At Victory, he’s made leaps and bounds,” his mother, Gayle Woodruff, says. “He’s so much more independent about things like getting something out of the refrigerator. It may sound strange, but when he does something naughty, in the background I’m going, ‘Yay!’ It means he’s being a normal kid.”

Victory Academy is developing with similar velocity itself. Founded in 2009 by two mothers of autistic children, Tricia Hasbrook and Thea Schreiber, the private school began with eight students in a single rented classroom in Wilsonville. Five years later, the academy now employs 28 full-time and five part-time teachers, teaching 38 students.

As if that growth arc were not ambitious enough, Hasbrook and Schreiber recently broke ground on a new 18,000-square-foot building on the outskirts of Wilsonville—after raising only 65 percent of its $5.5 million price tag. Their deadline for opening: September 2015. The newly housed school will be one of the only facilities on the West Coast specifically designed—from the floor plan to the LED lighting—to educate children on the autism spectrum. And everyone from the project’s architects to members of Portland band the Decemberists are pitching in to make sure the new Victory gets built.

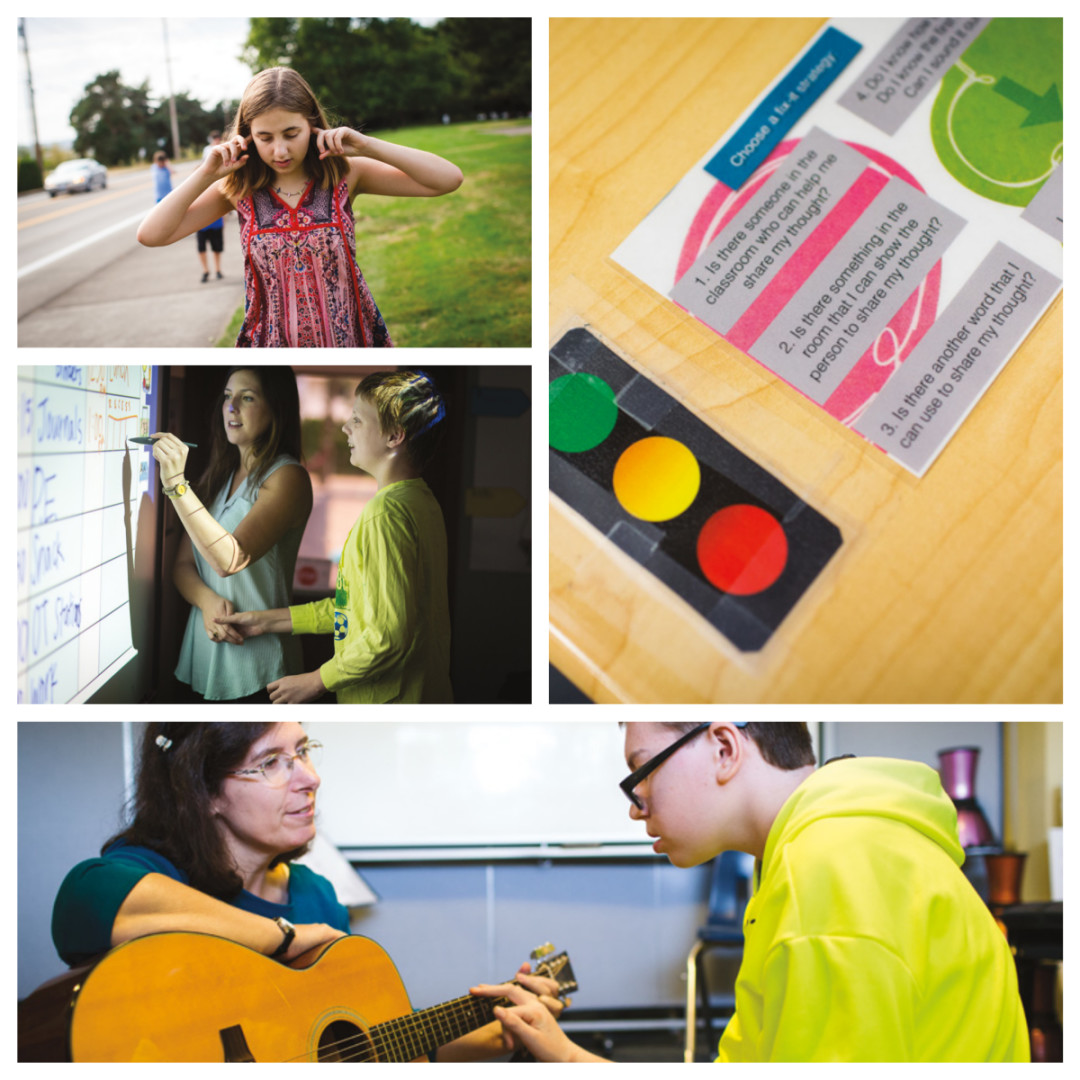

Clockwise from top left: Faith; Miles’s desk, offering reminders on how to sidestep communication obstacles; Emily Ross, a music therapist, gives A.J. a guitar lesson; teacher Molly Smith with Jamie.

Image: Leah Nash

No one yet fully understands why autism spectrum disorder occurs. Those with it often exhibit indifference to social engagements, an intent focus on a single object or subject, repetitive motions like rocking and biting themselves, and difficulty with verbal communication, among other traits. But every child on the spectrum—1 in 68 children, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—is also distinctly different: some are math geniuses or speed readers, others are unable to utter more than groans.

A.J., Hasbrook’s son, remains on the more severe end of the spectrum. Hasbrook and her husband, Bill, homeschooled him with behavioral therapies, between 40 and 50 hours a week, beginning when he was 18 months old and continuing until he was 7. His inability to speak or perform basic physical functions (a condition known as motor and verbal dyspraxia) led them to try exotic treatments like hyperbaric oxygen, horseback rides, even swimming with dolphins. (All of these approaches are embraced by many, and all are also clinically unproven as therapies for autism.) A.J. learned to read, but communication with his parents was limited at first to answering three- and four-part multiple-choice questions. He gradually learned to write.

Hasbrook remembers one of the first sentences A.J. scribbled, at age 8: “I’m so grateful that you all know that I’m in here.”

A.J. wanted to be around other kids, so his parents enrolled him in a private school. But at a 2003 Portland autism conference, Hasbrook met Schreiber, another Tualatin mother whose son, Zach, was on the spectrum. Their shared dissatisfactions with their education options quickly surfaced. The intensive homeschooling they had both provided their children could cost more than $65,000 per year. And dealing with autism requires time: hours and hours spent in therapies at home, hours and hours spent driving across the region for treatments. Private schools cost less, but parents still often had to contract with speech, physical, and occupational therapists not covered by tuition.

Hasbrook had worked as a teacher. Schreiber had a background in marketing. Together, they saw a niche to be filled. “We dreamed of this magical place where everything we wanted our kids to have would be in one place,” Schreiber says. The idea of doing it themselves was Hasbrook’s. They hatched their plan in the summer of 2008 and then proceeded at breakneck speed, opening Victory in fall 2009.

As the two women filed the necessary paperwork and raised capital, Schreiber’s son offered another source of inspiration. Zach transitioned off the autism spectrum after years of the combined therapies, becoming one of very few children to do so. “If you met him, you would not know his history,” Schreiber says. But she never considered dropping the school effort. “Autism had changed our lives, our roles as parents. It was our whole life. I did not want to walk away.”

Currently located in a rented annex of the New Life Church in Wilsonville, Victory draws students from five Oregon counties. Parents pay an annual tuition of $22,860, and the school raises an additional $7,000 per student to fund therapy services. The founders hope to begin offering scholarships after completing the new building, though Schreiber thinks that a summertime regulatory ruling requiring Oregon insurance companies to cover certain therapies for autistic children could trickle into financial help for some parents.

The kids are organized into five classrooms, not just by age but also by social cognition. The Fremont classroom is for high-needs kids, ages 5 to 8; the Hawthorne room has students, ages 10 to 14, who have often been mainstreamed for their elementary years but hit challenges in middle school. In the Sellwood classroom—which Hasbrook describes as the “hodgepodge class”—Miles and A.J. join other eclectically gifted and challenged students; Molly Smith, the 27-year-old teacher; and three aides. To an outsider, the ambience can seem one step short of chaos. But over a few weeks of observation,

successes emerge, like a conductor drawing separate melodies from the clatter of free-improv jazz musicians.

Image: Leah Nash

“Hey!” Miles calls with a wide inflection reminiscent of the Southern-fried 1960s TV character Gomer Pyle. Bailey, a 10-year-old student new to Victory, steps forward, bows, and extends her left hand like a friendly queen. Faith, 14, pays close attention to her nails, breaking for the occasional dancerly lap around the room. Ezra, an 11-year-old with a mop of hair and a Minecraft T-shirt, drums on his desk with a pair of plastic dinosaurs. A.J. practices balancing on an exercise device. Haley, the school’s therapy dog, wanders in and out, placidly accepting rough hugs. Their teacher, Smith, steps up to a large touch-screen in front of the class. The morning’s lesson begins: creating a shopping list for the weekly community-based learning field trip, which usually takes the class to a local store.

Smith is dark-haired and lightly freckled. She’s taught at Victory for three years and, like many of the teachers and aides at the school, exhibits a wry serenity. Using her large eyes like spotlights, she rotates her attention to the students one at a time, going through the shopping list, which is a collection of ingredients for dishes from countries competing in the World Cup. Each entry includes the name of an item, its price, and how many dollars it will take to buy it. She repeats her questions over and over. Math, logic, and focus are the goals.

Taped to the top of each desk is a list of reminders: “Ask my teachers to go outside when I need to move my body in a big way,” reads one of Faith’s. “Is there someone in the classroom who can help me share my thought?” reads Miles’s.

Bailey in class; Miles gets a shoe-tying lesson; Jamie, Miles, and Faith head out on a field trip.

Image: Leah Nash

Victory’s instruction is based on a regimen known as applied behavior analysis, or ABA, a technique that breaks both academics and basic tasks of communication down into small learning units, which teachers repeat until students master them. Early on, one such unit might involve striving to lengthen eye contact by a matter of seconds, or to shorten how long it takes for a student to respond when a teacher calls her name. In the Sellwood classroom, the ABA goals might include stretching Bailey’s ability to sit still in the class’s opening meeting, fostering A.J.’s purchase of a Frappuccino at Starbucks using his iPad, or encouraging Ezra to say, “Hi, Miles,” as he passes his classmate.

At other schools, weekly trips to stores, plus Friday outings to the bowling alley, might seem indulgent. At Victory, Smith explains, those trips impart academic, social, and physical lessons: asking for shoes, putting on shoes, tying shoelaces, sitting and waiting, typing names into bowling alley scoreboards, referencing the scoreboard to see whose turn it is, telling a friend it’s his turn, going into the correct bathroom.

“It’s not bowling,” Smith says. “It’s skill-building.”

Smith carefully logs each achievement. She also sends out a running log of posts and pictures of positive moments on a Facebook page accessible only to parents: A.J. smiling in the rain; Bailey, hand-in-hand with Ezra and Miles, leading them to the swing set; the entire class sitting still and looking at their teacher; Ezra recognizing himself on the Fred Meyer security cameras and breaking into a dance that the other students join.

Among autism educators, there are many theories and divides, but a big one concerns integration. Do kids on the autism spectrum learn better in separate classes, or among regular students? The arguments are partly behavioral: Will being around other autistic children reinforce behaviors not accepted by society, or do kids benefit more from positive peer reinforcement? But they are also partly political, and can echo the civil rights movement.

Ari Ne’eman, who heads the Autistic Self Advocacy Network and is one of the most strident voices for inclusion, has bluntly stated, “Segregated schools lead to segregated societies.” In contrast to Victory’s all-autistic student body, Portland Public Schools’ policy is pro-inclusion. “As a department,” reads the first page of its special-education web page, “we are committed to reversing the trend of isolation and segregation of students with disabilities....”

Hasbrook contends that Victory’s frequent trips offer the lessons of integration without cliques and bullying that often isolate kids on the playground, if not the classroom. Weekly visits to Victory by students from local high schools offer a two-way educational street: autistic kids learn from nonautistic kids, and vice versa. “These kids get plenty of integration at home with their families,” Hasbrook adds.

Colin Meloy, lead singer of the Decemberists, and his wife, artist Carson Ellis, illustrator of the couple’s best-selling Wildwood youth fantasy novels, tried enrolling their son Hank in PPS at first. A handsome child with a bloom of curly locks, Hank was devouring encyclopedias at 3 years old. But by preschool, he faced challenges, such as mastering throwing a ball, or the socialization necessary to sit with other students in a circle. Unexpected chaos in a classroom coat closet could trigger a tantrum.

“We wanted to give inclusion a shot because we are supporters of the idea,” Meloy says. “Plus, it’s PPS’s legal obligation to educate these kids.”

Hank started in a mainstream preschool and moved on to kindergarten at Skyline Elementary. But the school had no dedicated classroom for special-ed kids. The nearest of these classrooms, which PPS sprinkles through the district, was a 30-minute drive from their home, and it extended only to second grade. And the specialized classrooms, Meloy and Ellis believed, were too crowded, with teachers overwhelmed by the range of special needs—from autism to Down syndrome to other kinds of developmental differences. When Hank moved on, he would leave friends, teachers, and social continuity.

Jen Thessin and Gavin at Victory Academy

Image: Leah Nash

But Meloy was equally troubled by what he calls “a lack of real commitment to inclusion.” Hank, he recalls, was invited only to watch a winter choral concert—not to participate. On field trips, all the kids had name tags, except for those in special ed. On one art field trip, special-ed kids didn’t receive the same supplies other students did. “These are little oversights, but they attest to a lack of inclusiveness,” Meloy says. “It has to be something everybody is into.”

Meloy and Ellis could live anywhere. They investigated schools from the Bay Area to New York. Though newer and scrappier than many, Victory showed just as much promise, without the risk of a disruptive relocation. “What if you moved to San Jose,” says Meloy, of a city with a number of autism-oriented schools, “and things didn’t work out?”

Hank is now in his second year at Victory. There have been “bumps in the road,” such as a change in teachers. But Meloy believes the school’s wider focus on simple social behaviors and the more integrated regimen of therapies has benefited his son hugely. “Hank’s so smart, but around other kids he knows he’s the odd man out,” he says. “Focusing on things other than academics, like ‘Hey, you had a great day hanging out with Max. That was awesome,’ is as important as math. There are several people at Victory who really get him and understand this incredible gift of how hilarious he is. You have to have an appreciation of the autistic mind.”

With only a low-key mention of Victory Academy, Meloy and his band, the Decemberists, played a benefit for the school’s new building at the Crystal Ballroom in May. The performance netted $165,000. Hasbrook and J. B. Handley, cochair of the school’s capital campaign (and parent of a student), are inching toward their $5.5 million goal. The largest individual contributions so far have been an anonymous $400,000, and $100,000 from a foundation. Yet in a move that would leave any professional fundraiser stunned, Victory started its building before getting even close to finishing the capital campaign. “We have to,” Hasbrook says with a shrug. “Our lease is up on August 31 of next year.”

Hasbrook’s confidence is contagious. An April donors’ luncheon, at which she shared students’ stories and a choir of Victory students sang, brought in $395,000, mostly in $10,000 dollops. The Portland firm Opsis Architecture, along with a team of mechanical, structural, and environmental engineers, steeply discounted design fees. “It’s so compelling what Victory is doing,” says Opsis cofounder James Meyer. “But I also felt they could pull it off.”

Opsis designed the new facility specifically around students’ needs, as well as the school’s therapeutic curriculum. Light, color, chemicals, and noises can trigger behavioral issues in autistic kids. So natural, northern light will bathe Victory’s hallways. Mechanical systems will be quiet. Instead of buzzing fluorescent lights—known to be problematic—Victory will feature silent, flexible LEDs. Meyer’s team is even exploring apps that could allow the students and teachers to tune preferred light colors for their rooms.

Each classroom will adjoin “breakout” rooms to be used for therapies, or to let off steam in a meltdown. Speech and music therapy spaces have sharp acoustics. But the designers have been careful not to sanitize the building too much. Meyer recalls Hasbrook telling him that the old-school prank of yanking the fire alarm, “depending on which kid [does it], could actually be a good thing.” There will be laundry and kitchen facilities to teach basic home skills. Bathrooms will feature a variety of water faucets on the sinks: two-handled, one-handled, and motion-activated.

“In the real world, everything everywhere is different,” Hasbrook says. “It’s going to look like a mishmash, but I don’t care.”

“When I go to Victory, I just crawl back out, it’s so emotional,” Meyer says. “I’m stunned by the culture of patience and lack of judgment. These kids are bigger than life. They deserve a good building.”

On a hot July afternoon, the Sellwood class hops a bus for a trip. It’s Miles’s 11th birthday, so he gets to choose, and they are going to Target. Miles’s growing command of communication has revealed a deep interest in brands. (When Smith led the class in a study of the various World Cup countries’ cultures, Miles chose Argentina and began researching the country’s products.) “I love Target,” he says. His shopping list for the day includes Silk almond milk because he likes the TV commercial—“50 percent more calcium than regular milk,” he says, echoing the ad—and Yoplait yogurt “because it’s so good.” Ezra says he wants to give Miles Froot Loops for his birthday. Smith points out that this is significant: he’s expressing that he is thinking about his friend.

The class enters the store. A.J. wears a T-shirt that reads: “Not being able to speak is not the same thing as not having anything to say.” At the store’s entrance, Miles waves and gives his Gomer Pyle “Hey!” to a pair of scruffy kids with a dog, momentarily becomes distracted by displays of Clorox and DVDs, and then begins wheeling a cart toward the day’s choices. Bailey lurches ahead, wanting Miles’s cart. Smith leaps after her. “We’re practicing waiting,” Smith says as she steadies Bailey. She pulls out her phone and sets the timer for two minutes, the time when she’ll let Bailey have the cart—in ABA lingo, “delayed reinforcement.”

Breyers ice cream is on sale, three for one. “Should we get three?” Smith asks. Miles offers a mirthful scolding: “That’s just plain old silly.” He quickly transitions to a hunt for the cereal, his focus and ability to figure out the logic of the aisle markers’ color coding becoming one of the day’s measurable successes. “I love General Mills stuff,” he says. Ezra finds the Froot Loops, but the advertised special treat inside inspires him to rethink whether he wants to give them away.

Back at the school, Miles’s mom, Gayle, arrives with dairy-free ice cream sandwiches. Smith helps Miles open cards from the other students. “Miles makes me feel happy,” reads Faith’s, with a photo of them together. “I can REST with Miles.”

A student from the Hawthorne class next door wanders in and asks Miles, “How was Target?” Miles lifts his head to look through his glasses and offers his response: “Expect more, pay less.”