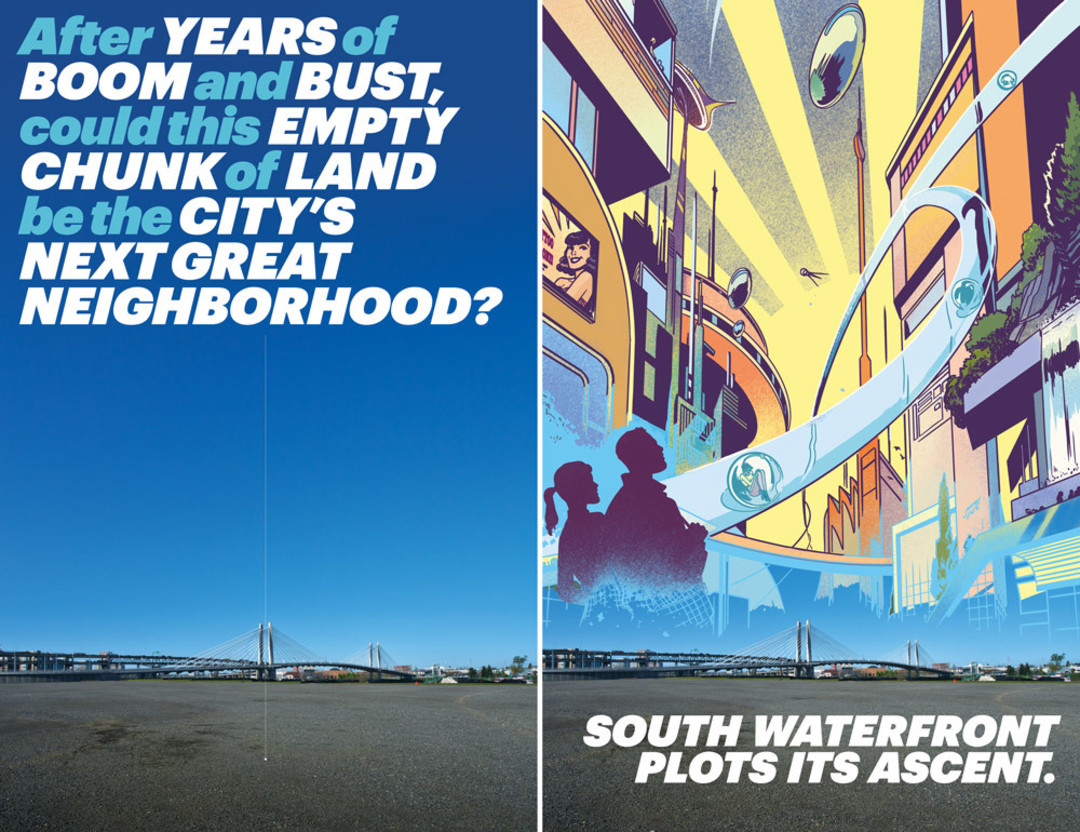

Is South Waterfront Portland's Next Great Neighborhood?

Image: Jonathan Case

One day last October, a pop-up tent in South Waterfront sold dahlias for $3 a stem. The tent was unstaffed, as was an adjacent full riverfront block planted with Halloween pumpkins. The honor system seemed perfectly suited to SW Curry Street’s mix of humanity that afternoon: runners with dogs in tow, elderly strollers, med students in scrubs catching some midday sun. Not that much sun reached the street. The skyscrapers of South Waterfront, a neighborhood that looks like a pocket metropolis along the Willamette River, kept the sidewalk in perpetual twilight, like the urban canyons of Manhattan and Vancouver, British Columbia. But a pumpkin field amid the glass-skinned high-rises suggested an all-Portland ethos—a hybrid of soil and steel, industry and urban pioneering.

South Waterfront first rose about a decade ago. The city, private developers, and Oregon Health & Science University, Portland’s largest employer, assembled a boggling combination of funding, zoning, ambition, and salesmanship to create a new high-rise neighborhood on old industrial land on the Willamette’s western bank. They wanted to emulate high-density urban districts elsewhere and provide growing room for OHSU, which aims to become one of the nation’s major research facilities.

The vision came packaged with aspirational trappings—luxury senior living, commanding penthouses—and the transformation proved both dramatic and controversial. Were glass towers and a space-pod tram to OHSU’s hilltop headquarters evolutionary, or antithetical to Portland’s modest psycho-geography? Or should these old questions even be asked of a new neighborhood?

The shimmering towers did feel a bit grand and, as a business venture, troubled. After the first rush of building, begun in 2004, South Waterfront stalled hard, most directly because the Great Recession deep-sixed the real estate market. (There aren’t many other ways to explain a penthouse originally listed for $4 million selling for $1.4 million.) Five years ago, the words “South Waterfront” and “boondoggle” often appeared in the same sentence. But in a deeper sense, the neighborhood didn’t spark. Tall buildings don’t make a city. A city needs enough sex appeal to lure people’s time and money and to kindle ideas.

In 2015, South Waterfront is getting sexed up. It’s also proving more flexible than its origins as an insta-neighborhood portended. That pumpkin field was never on any developer’s master plan, but there it was, briefly—and now it is gone. By next year the field will be a hard-hat zone for one of many new structures that will further transform the area as major players resume building—big, but also differently—in a changed economic and cultural era. Zidell Marine Corporation, a family business based in Portland for nearly a century and in South Waterfront since 1930, joined the area’s first major investors in 2012. The company controls 33 acres of undeveloped waterfront, central Portland’s last great tabula rasa for urban placemaking. The first Zidell-developed building, an apartment block called the Emery, launched in 2013; the family plans to develop 1.5 million more square feet of residences, offices, and shops over the next decade. OHSU will develop another million square feet in South Waterfront over the next four years. Construction is so rampant, the local charter school put a crane on its T-shirt.

What South Waterfront will look like in 10 years is not known, the model as yet elastic. What is being built there now is at an aesthetic pitch that Portland has not seen, oriented to the city’s great constant: the river.

“It’s Portland’s Brooklyn Bridge,” says Bob Hastings, admiring Tilikum Crossing from its west end. The cable-stayed bridge glows white in the moonlight, its twin crests rising like the wings of a giant egret. An architect with TriMet, which built the $135 million bridge, Hastings scrolls to a video on his phone, showing a test of the bridge’s dynamic lighting system, devised by a team of San Francisco designers.

“They figured out how to take the United States Geological Survey data of the Willamette by the Morrison Bridge and feed it into the lighting controls,” he says. The river itself—its height, speed, and temperature—will determine how the bridge looks from moment to moment. In Hastings’s video, the lighting shifts from aqua to pink to gold, what Hastings calls “an aurora borealis feeling.” When it opens in September, spectacle aside, Tilikum Crossing will be the first cross-river artery directly into South Waterfront, carrying the new MAX Orange Line, the Portland Streetcar, bicycles, pedestrians, and buses, but no private cars.

Hastings and his wife downsized from a Beaumont house to a South Waterfront condo in 2008. “We wanted to reduce our carbon footprint and get rid of one of our cars,” he says. They did. They also saw their anticipated urban experience burst along with the real estate bubble. Within months, the occupancy of their building dropped to 12.5 percent. Entire floors of the 23-story tower sat empty.

“It was eerie, but we weren’t there just for the short-term,” he says. “If there was a hiccup along the way, well, that’s Oregon.” Twenty-first-century homesteading meant creating a community garden with neighbors; watching developers turn condos into rentals and the demographic grow younger; seeing streets, “ghost towns at times,” sprout businesses, a slow vivification he found encouraging, if not quite what he’d imagined.

At the time, South Waterfront 1.0 abutted Zidell Marine’s barge-building operation, which included a brownfield where asbestos, lead, and other pollutants had been dumped for decades. “Lewis Mumford has this quote from the 1930s, when he challenged Portlanders,” Hastings says, paraphrasing the great urbanist. “He said, ‘You’ve got this beautiful place. Are you good enough for it?’ The short answer for Zidell was, no, they weren’t.”

And then, slowly, they were. In 2012, the company completed a voluntary $20 million cleanup and appointed Matt French, the then-29-year-old great-grandson of founder Sam Zidell, as managing director of the family’s new development arm, ZRZ Realty. He proceeded to travel to some of the world’s great river cities and set a small construction trailer in a gravel lot by the Willamette, inviting some early neighborhood residents, including Bob Hastings, to come visit.

“It was kind of a dream shack,” says Hastings. “Every wall was festooned with pictures they had taken from around the world. They were saying, ‘Here’s our vision to extend that original, incredible, bold move by developers. But we’re going to do it from our generation’s perspective.’”

On a sunny fall day, Matt French stands by an east-facing window in the Emery, a seven-story building that was the first completed ZRZ project. From here, he can see Tilikum Crossing and the latest barge built by Zidell, South Waterfront’s first high-rises and, beyond them, the Willamette itself.

“I was paddleboarding two nights ago,” he says. “The sun was setting. The bridge was awesome.”

French wears a crew-neck sweater and the sort of cream-colored stovepipe jeans one sees on a prep school kid—which the tall, doe-eyed 31-year-old could pass for. A Lincoln High graduate, he majored in business at the University of Southern California and worked for a Los Angeles hotel group before returning to Portland in 2010 to spearhead what he says his family long intended: development of its South Waterfront land. There was nothing on the newly branded Zidell Yards: no city street grid, no water or power. French could essentially draw a 33-acre neighborhood from scratch.

“That’s an opportunity for us—perhaps a challenge—to draw on other cities with world-class ambitions,” he says, adding that he takes particular inspiration from Copenhagen. “It has a really nice design sensibility around the public spaces. They definitely prioritize, for example, the waterfront. It just feels good.”

There was also legacy to consider. Much of OHSU’s South Waterfront development was slated for ex-industrial land donated by the Schnitzer family, who, like the Zidells, came from Russia in the early 1900s and started in scrap metal. Some of Portland’s largest civic institutions bear the Schnitzer name. How would history remember the Zidells, as old-economy polluters or as new-economy creators?

If ZRZ had visions of 20-plus new buildings, they needed to sell the dream. The family firm brought in Jelly Helm, a former Wieden & Kennedy creative director now running his own marketing studio. “Big visions and visionaries have always been attractive to me,” says Helm, whose clients include Wikipedia and the Portland Timbers. “I began the project with a lot of the same biases that other people have about South Waterfront. Wasn’t that a failed project? Empty condos? But it just took one visit to see the property as a special piece of land. Matt believes he can steward it toward becoming one of Portland’s great neighborhoods.” Helm created a 16-page, sepia-tinted broadsheet illustrating the family’s history on the property. One photo, taken from the air in the 1990s, showed a garbage-gray industrial waterfront. The climactic final rendering, however, showed the area as it might one day be: the land rehabilitated, the river slate blue.

Populating this vision requires buildings, certainly. But it also requires that Portlanders think of South Waterfront as a place they actually go—and so last summer Zidell Yards transformed into a temporary cultural hub. An improvised drive-in showed Purple Rain and Mean Streets; the Violent Femmes and Tears for Fears headlined a three-day concert series; and the food festival Feast’s Asian-inspired Night Market saw thousands eating and drinking under paper lanterns and the night sky. Soon many culturally attuned Portlanders who had never been to South Waterfront knew that it lies just 1.4 miles from downtown, with more distinct ways to get there (car, bus, streetcar, aerial tram, pedestrian bridge, bike, foot, kayak, etc.) than just about any place in Portland. Several thousand people shifted their thinking: South Waterfront was no longer a district of glass ghosts, populated by a few rich people wandering penthouses 300 feet in the sky. From French’s perspective, the whole penthouse idea seems 20th century.

“Companies want to be more democratic, less top-down, more flat, more connected, more open,” he says of his decision to plan long and low, along the campus model that tech companies have used for years, with the hope of luring major employers alongside residents. If verticality once imposed hierarchy, the horizontal now insinuates parity. Everyone wears jeans; everyone works on the same floor.

“It’s fascinating how real estate can support all of those things companies need and are looking for,” says French. “The game is changing.”

As one might expect of such a grand plan, the Zidells have encountered turbulence—there’s been considerable controversy over how (or whether) they’ll build affordable housing, for example. But their first foray into residential building does feel more egalitarian than the towers immediately next door. The Emery emphasizes communal on-site amenities and gathering spaces, and its ground-floor tenants, all local businesses, share a front porch.

“It’s just a mash-up of different kinds of people: workers and students and researchers and faculty,” French says.

For now, future and past rub against each other. The Zidell Barge Building, across from the Emery and just south of the Ross Island Bridge, could accommodate two jumbo jets parked end to end. This past November, the latest vessel built in this “barge shed”—a 422-foot petroleum hauler, six million pounds without its payload—floated nearby. Wind turbine lathes and rusted I-beams, anchors and lengths of chain with 45-pound links, did not appear poised for recommission. That bright Jelly Helm rendering, in fact, showed no barge shed, no iron detritus.

“It is more a suggestion of possibilities—a field of dreams, if you will,” says French. “We’re not going to replace the barge building right now.”

Heather Bayles, director of South Waterfront Community Relations, works from a table at Lovejoy Bakers on the Emery’s ground floor. Until recently, Bayles and the neighborhood association’s other employee had their pick of empty condos in which to set up shop.

“Donated space is a thing of the past—a wonderful problem,” she says, walking along River Parkway, which smells distinctly of that byproduct of city living: dog poop. She stops into a restaurant called the Groaning Board, where a server who might have had seven cups of coffee for breakfast reports: “We’re doing a hundred people a night! We’ve been open two weeks!” She passes the lot where Bob Hastings and his neighbors once planted their garden, now a six-story building under construction.

“There’s room for everything—until everything changes,” she says, continuing to the greenway by the river. She mentions 100 percent condo occupancy and a booming farmers market. It was all good news, and led inevitably to displacement. “Our first office, we could see the river and Ross Island,” she says, looking toward the river. In the half-burnt-off morning mist, the island looks like a painting of an unchanging, primordial landscape. Not so. “The island was always different,” she says, “always changing. The light, the trees. I loved it.”

On paper, the Collaborative Life Sciences Building and Skourtes Tower are impressive: LEED Platinum, $295 million, harnessing programs from OHSU, Portland State University, and Oregon State University. In person, the 12-story teaching and research facility, opened on South Waterfront’s north end in summer 2014, is arresting. A massive, asymmetrical silver cube set on support beams, the Life Sciences Building hovers like a ship from Battlestar Galactica. A vaulted interior at once suggests both Gothic cathedral and a beehive, with floating catwalks and platforms warmed by honeysuckle-colored LED lights that seem designed to keep seasonal affective disorder at bay for the medical and dental students who study here.

“We did not want brick and ivy,” says Brian Newman, OHSU’s associate vice president for planning and development. “We wanted a new campus. It’s a new century.” Standing on the terrace behind the new complex, Newman looks south to OHSU’s Center for Health and Healing, which opened in 2007. The billion-dollar Knight Cancer Research Center is on target to open to the north in 2018. To the southeast, the lot where the dahlia field once grew is slated to become a construction staging area for the school’s new ambulatory care center.

“When the bridge opens, that will be a big inflection point,” Newman says.

Tilikum Crossing and the Life Sciences Building seem like more than inflection points. Sitting astride the neighborhood’s north end, they make a bold statement: a billion-dollar bet on what can happen here. In 10 years or 20, will South Waterfront still feel like a faintly futuristic experiment, or will it be knit into the city as a whole, a neighborhood per se, dramatically different but just as loved as brick-clad Northwest or leafy Laurelhurst? And if the latter, what kind of neighborhood? Right now, the feeling is electric, the effect incandescent. And who will see it? Who will respond? World-class teams of scientists have already gravitated here, and there will be more. South Waterfront could be the next phase of Portland’s ascent in the nation’s estimation. Coffee and doughnuts are great; now, watch us help bring the world a cure for cancer.

And what will the world bring Portland? Looking at the Life Sciences Building or Tilikum Crossing, it’s not hard to imagine a suite of transformative buildings here. “The tram was a result of an international design competition,” Newman says. “And I think—I hope—there might be opportunities with specific projects.”

As for Matt French, he continues his regular trips to places like San Francisco and Victoria, New York and Amsterdam, gleaning from other cities what might best be done here. Could some provocative Dutch genius or future-forward Japanese visionary achieve their next important structure on the banks of the Willamette?

“That,” says French, “would be pretty cool.”

Editors' Note: The original text of this story was revised after publication to reflect Portland State University’s involvement in the Collaborative Life Sciences Building and Skourtes Tower.