Wendy Red Star Totally Conquers the Wild Frontier

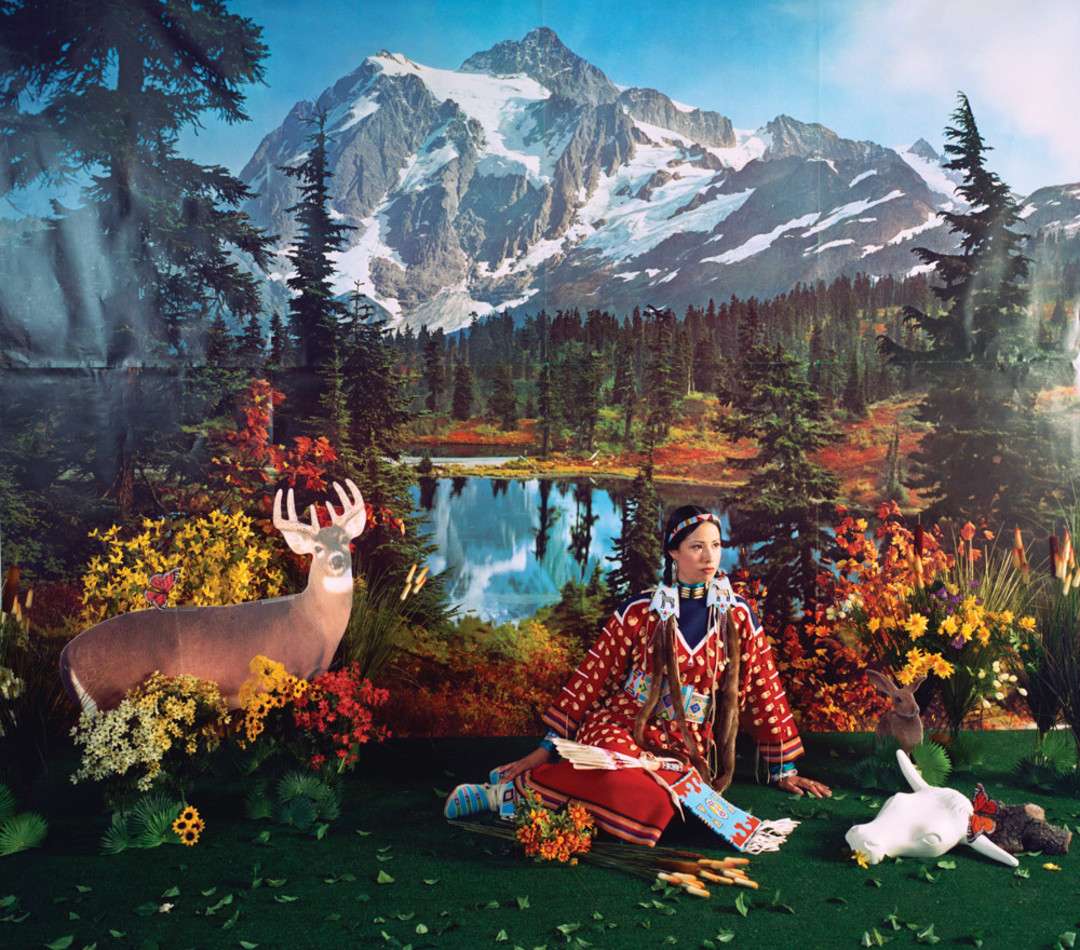

The photo series Four Seasons has become Wendy Red Star’s best-known work. In images like Indian Summer, Red Star poses as a Pocahontas-style “Indian maiden” in a Crow elk-tooth dress, traditionally a marker of a wealth. Her faux-naturalistic surroundings consist of cheap, mass-produced props, like inflatable animals and artificial turf.

A battery-powered miniature Lexus—one of those absurdly expensive plastic toys that little kids can actually drive—sits in the middle of the floor, ready to be decked out with flamboyant decorations, like the cars and trucks that parade during powwows on Montana’s Crow Reservation. A dressmaker’s form in the corner is draped with a dress patterned on a buckskin garment traditional to Crow Nation women, but made out of red vinyl, studded with rhinestones, and inspired by Michael Jackson’s gleaming ’80s jackets. To Wendy Red Star, whose Northeast Portland studio (also her living room) holds these objects, mash-ups of mass-market and Crow culture make perfect sense.

“I don’t ever do this,” she says, explaining the dress, “but I sat down with a tarot reader one day. She said, right now, you’ve gotta be Michael Jackson. Not crazy Michael Jackson, but Michael Jackson the artist: super-focused, totally in charge.

“There are definitely aspects of my art,” the 34-year-old adds, “that you’d never get if you didn’t grow up on the Crow Reservation.”

Even so, Red Star is enjoying a moment (her Michael moment?) in the wider art world. New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art includes her work in a current exhibit of Plains Indian art, and Dartmouth College’s Hood Museum is showing her self-portraiture alongside big names like Chuck Close, Cindy Sherman, and Bruce Nauman. Red Star will stage 15 separate exhibitions this year, on the heels of a late-2014 Portland Art Museum solo show.

“This last year has been an explosion,” she says. Or, as she posted to Facebook recently: “I understand why I feel batshit crazy.”

Red Star belongs to a generation of Native artists whose work can be funny, brash, and surreal. (To throw out a few names: a group show Red Star curated last year included Demian DinéYazhi’, a multimedia-inclined Portlander originally from New Mexico; Amelia Winger-Bearskin, a tech-oriented New York artist; and Skawennati, a Canadian whose work includes a project called Aboriginal Territories in Cyberspace.) These artists often don’t so much battle stereotypes of Native American art as gleefully flip them on their head.

“There’s a whole notion of being ‘authentic,’” Red Star says. “Your art is supposed to look like the 19th century, like we’re a dead culture that never evolved.”

In Hipster Headdress Warpath, Red Star and a model don low-budget Halloween costumes from Target. “This kitschy stuff is part of who we are now, too,” she says, “so we’re embracing it.” (The piece also comments on the unfortunate fashion vogue for pseudo-Native headdresses.)

Red Star’s work is many things: satirical, self-aware, and usually electric with saturated color, a quality she calls “totally a Crow thing.” Dead? Definitely not.

Red Star grew up on the 3,500-plus-square-mile reservation of the Apsaalooké Nation. (“Crow” is an English mistranslation of “Children of the Long-Beaked Bird.”) With fewer than 8,000 enrolled members on the reservation, Crow country is sparsely populated, but just 10 miles from Billings, Montana’s largest city. While poverty runs high, Crow land sits atop billions of tons of coal, making the tribe a major energy-politics player. Compared to many tribal languages, Crow remains in fairly broad use, and the summertime Crow Fair is one of the continent’s largest Native festivals.

Thus Red Star grew up in a rural community that’s also a sovereign nation and cultural powerhouse. She loved powwows and horses, and remembers her grandmother, Amy Bright Wings Red Star, creating traditional outfits—“sitting there, listening to powwow music, making beadwork.” Her father, a rancher and licensed pilot, once played in an all-Indian rock band called the Maniacs. Her sister, a Korean adoptee, spoke fluent Crow as a child, which Wendy herself did not. She describes her mother, an Irish-American public health nurse, as “a total white lady who’s more Crow than I’ll ever be.” (Red Star says her mother knows almost everyone on the reservation and encouraged her daughters’ Crow cultural pursuits: Wendy served as “princess” for the tribe’s Piegan clan, for example.) An uncle, Kevin Red Star, is a renowned painter.

At Montana State University, Red Star studied sculpture—in Bozeman, a pursuit low on theory and high on practicality. “You have to learn how to weld and use wood tools,” she recalls. “And you have to do everything yourself, or you’re not a real artist.” But she also began making conceptual statements. After she learned that a treaty once defined Bozeman as Crow territory, for example, she harvested pine poles from the reservation and built tipis across campus. She would go on to a master’s in fine art from UCLA, a program led by heady art stars like Charles Ray, whose work includes unsettling fiberglass nudes.

“I get really deep into research,” she says, “and I discovered that the best way for me to communicate what I learn is in a 3-D creation: let me make this really weird thing to show you.”

For the 2011 photo-tableau series Thunder Up Above, Red Star combined European and Victorian fashion motifs with ’70s silhouettes and Native American design. She photographed herself in her bedroom, then used Photoshop to create fantastical interplanetary landscapes. The sci-fi results evoke the intrigue and suspicion of “first contact” with an unknown people—or, as she put it in her artist’s statement, “someone you would not want to mess with.”

In 2006, her marriage to a Portland artist brought Red Star to Oregon. (They’ve since divorced.) Her 7-year-old daughter, Beatrice, now attends school in Portland, while Red Star works in Vancouver for a Native American arts nonprofit. She thus does her art at night and on weekends. True to her craft-oriented training, she stocks her home studio with smoked and bleached animal hides—deer, elk, and pig. While much of her work begins with riffs on Crow garments, her final pieces tend to be kinetic combos of handmade and high concept, executed in diverse media. For a June fashion show in Kansas City, for example, she plans dresses covered in bells and feather bustles, each supersized from one element of male “hot dance” costumes.

Clothes aside, Red Star unites political, comedic, even fantastical elements. For White Squaw, she superimposed her own goofy expressions onto the covers of racist 1980s paperbacks, keeping the sexpolitation text (“She sees what’s coming and blows her way out of trouble!”). For 2011’s Thunder Up Above, she constructed “futuristic powwow” costumes and sci-fi landscapes—a new frontier of her own, peopled by “fierce ambiguous beings.”

“Wendy’s work isn’t about being a victim, or bemoaning colonialism,” says Terrance Houle, a Canadian artist of Blood and Ojibwe ancestry with whom Red Star has collaborated. “It has a definite Indian sense of humor, and it’s bright and beautiful, and that’s an aspect of indigenous culture people don’t often see.”

Houle is one of Red Star’s art-world comrades whose work turns on Native identity. Her collaboration with him includes a role in his National Indian Leg Wrestling League of North America, a performance/installation/joke that mixes Native stereotypes with pro-wrestling theatrics. Similarly, much of Red Star’s work makes ironic use of Native Americans’ historic deployment as “exotic” performers. She titled her group show for Seattle’s Bumbershoot festival last year Wendy Red Star’s Wild West & Congress of Rough Riders of the World, appropriating branding from Buffalo Bill’s extravaganzas.

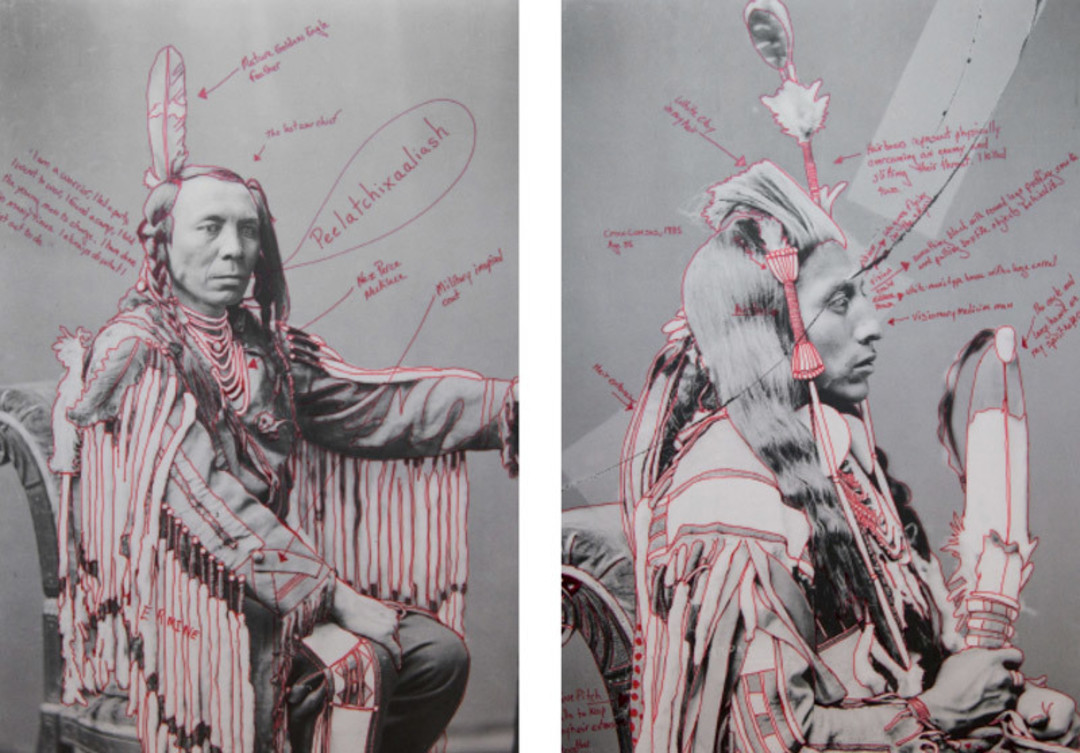

For her Portland Art Museum show in 2014, she revised photos of an 1880 delegation of Crow chiefs visiting Washington, DC, for treaty negotiations. C. M. Bell’s original portraits are beautiful, but became generic icons of “Indian warriors”—to Red Star, just another example of white culture treating Native Americans as human museum pieces. (Bell’s profile of the chief Medicine Crow was used as a tea company logo, for example.) Red Star annotated Bell’s photos, noting, for instance, that Medicine Crow’s hair bows signified that he had slit the throats of two enemies in battle.

For a 2014 solo show at Portland Art Museum, Red Star annotated 19th-century images of Crow chiefs.

“I get obsessed with the actual stories,” says Red Star. “That they went to the DC zoo, and Medicine Crow felt compelled to make up a Crow word for ‘giraffe.’ That they wore hair extenstions gathered from people in mourning. You can give people their identities back. Medicine Crow had this weird, wicked sense of humor. Years later, he and some other guys killed some horse thieves. He cut off one of their hands. He shook hands with the reservation’s federal Indian agent—with the dead horse thief’s hand. The fact that this one guy had this bizarre sense of humor—I want people to know that.” Medicine Crow becomes a real person, forging into a strange new world.

In March, Red Star went to see her work at the Met. On Facebook, she posted a Manhattan cityscape—the scene, of course, of the archetypal white/Native land heist—snapped from the 51st floor of Trump Tower. Using the traditional term for honor won in battle, she wrote: “Counting coup for the Piegan clan.”