Reflecting on the Past, Present, and Future of Portland's Pearl District

On a warm evening shortly after I arrived in Portland, an artist friend toured me around “places I should know about.” The year: 1990. The neighborhood: close-in Northwest. We savored the glittering, inner-city industrial spectacle of aluminum dunked at a galvanizing plant. We knocked back bourbons with the Radio Cab drivers at Yur’s. And then we wandered to the highlight: the decades-old, Greek-myth-inspired graffiti adorning the concrete columns holding up an elevated roadway then called the Lovejoy Ramp.

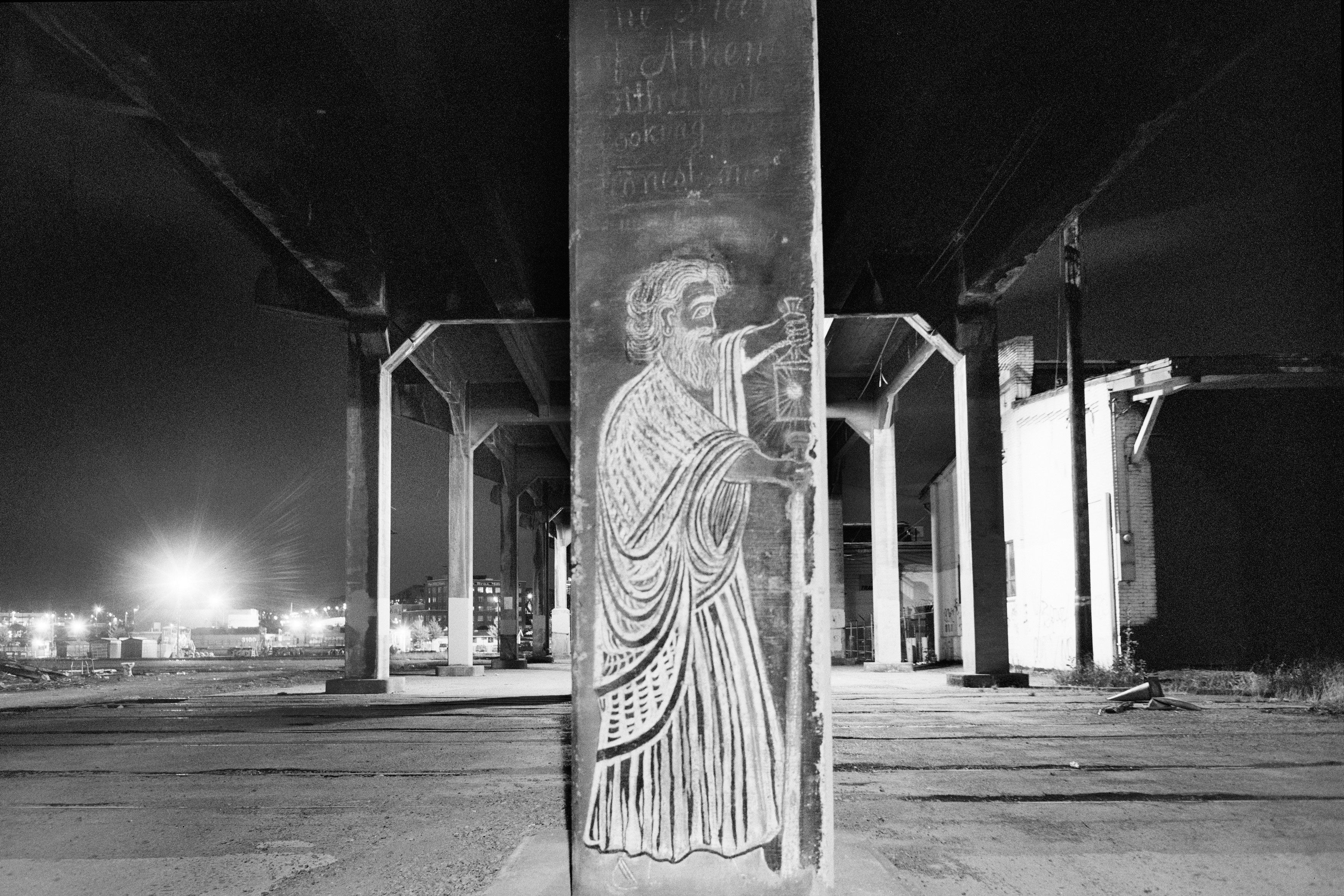

In hues of cerise, orange, and peacock blue, chalk lines and swabs of paint climbed the pillars like vines, conjuring mythical owls and beasts, fanciful flora, and a portrait of Diogenes, lantern hoisted high. Drawn circa 1950 by a classically trained Greek immigrant and night watchman, Tom Stefopoulos, the artworks had memorable cameos in Gus Van Sant’s Drugstore Cowboy in 1989 and would later appear with Elliott Smith in a short film called “Lucky 3.” Like some sort of hobo version of the Chauvet Cave, they seemed sacred. An introduction from a knowing local felt like a rite of Portland passage.

A few blocks away, a place we now call the Pearl District was germinating. Eventually, this new neighborhood was destined to displace the columns—along with most of that lost-city grit my friend and I toured—with a globally celebrated example of innovative urban redevelopment. Over the ensuing decades, as a journalist and critic covering architecture and development, I’d write about the neighborhood’s rapid transformation—and about the columns’ plight.

Today, as buildings rise on the last of the Pearl District’s empty land, and plans commence for 12 more blocks next door as the huge central US Postal Service facility prepares to move, it’s a good time for reflection—on the fate of Stefopoulos’s paintings and the quality of the gradually maturing neighborhood.

According to lore, the Pearl began as an artists’ district. That’s only sorta true. Sure, in the late ’70s, artist Tad Savinar, filmmaker Van Sant, and a handful of others had storefronts or lofts in the district. By the mid-1980s, galleries like Quartersaw, Blackfish, and NW Artists Workshop roosted there. On a rainy September night in 1986, the First Thursday gallery walk began, and a loquacious, rather kitschy gallerist invented a perky new neighborhood brand, the “Pearl District.”

But the real genesis story is a bit less romantic. Developers like John Gray and Al Solheim and former junk peddler Ken Unkeles bought up old industrial buildings in the wedge of land north of Burnside and east of I-405 and converted them to self-storage and Class C office space. A pivotal 1983 American Institute of Architects study of the district, “The Last Place in Downtown,” laid the groundwork for designating NW 13th Avenue as a National Historic District. The corresponding tax breaks proved a powerful fertilizer. In 1986, a group of investors bought 40 acres of largely empty railroad land stretching north of NW Hoyt Street for $6 million—about 30 cents per square foot. Two years later, Solheim and Gray pioneered the district’s first official residential conversion, the Irving Street Lofts, and a short walk north, Bridgeport Brewing Co opened its first brewpub.

Visions abounded. Some foresaw a new home for the Trail Blazers; others, a golf driving range. Influential urban designer Greg Baldwin pitched a huge, amphitheatrical bay carved out of the Willamette’s banks. What actually came to pass, however, was more a nuts-and-bolts collaboration between innovative, but hardened, realists.

By 1994, a new group of partners bought that 40 acres: Hoyt Street Properties, led by consummate dealmaker Homer Williams, who’d developed Forest Heights, and the deep-pocketed Joe Weston, one of the region’s largest apartment and office park developers. Meanwhile, ambitious urbanist Vera Katz sat in the mayor’s chair. The city’s powerful Portland Development Commission, still narrowly focused on urban renewal, employed a sharp negotiator named Bruce Allen. Slowly, this small group crafted a three-part pact to steer the creation of a new urban neighborhood that would become the densest in the region and the envy of developers, mayors, and urban planning wonks worldwide.

The first move: the city would tear down the Lovejoy Ramp, regarded as a barrier dividing the future neighborhood. For that, the developers agreed to build a minimum of 87 housing units per acre through the district. If the city built a streetcar, the developers would raise the ante to 133 units per acre. Three new city parks would net at least 150 units per acre. Thirty percent of the housing, the developers and city pledged, would be affordable.

And so the wrecking ball took aim at Stefopoulos’s columns.

In 2000, as the deal took shape on the ground, I pedaled my bike between the freshly laid streetcar tracks, past a fence protecting the newly cleaned-up railroad lands, and came face to face with the backlit visage of Joe Weston. Decked out in a three-piece ice cream suit, with a cane and a wide-brimmed straw hat, he surveyed his domain as proudly as a dandy frontier banker. Ambling by me, he chirped, “Good day!”

Those were the Pearl District’s Wild West days: big characters, big moves, and even bigger dreams. A group of artists and architects persuaded the city to save Stefopoulos’s paintings. In a procession led by an accordion-playing Alicia Rose and a pajama-clad James Harrison, a truck hauled 10 amputated pillars to a patch of nearby empty land to “sleep” beneath tarps, in hopes the “gods of commerce, cash flow, and capital” would one day awaken them.

Landscape architect Peter Walker—now best known as the codesigner of the National 9/11 Memorial’s plunging black fountains—laid out a plan for the three promised parks, connected by a wide, wood-planked boardwalk that he envisioned rising in a bridge over the railroad tracks to the upper stories of Centennial Mills, a rotting industrial hulk that preservationists hoped to be a historic icon at the Pearl’s northern edge. Walker also designed the neighborhood’s first park—Jamison Square—with a cascading fountain that, from its opening day in 2002, drew frolicking kids from throughout the city. Across the street, next to the streetcar, one of the earliest new buildings took shape: the Pearl Court, with 199 units of affordable housing.

Loft conversions came, and then “faux” lofts—new buildings like the Gregory and the Elizabeth. Instead of paving the area’s potholed roads in new asphalt, city crews replenished some streets’ original cobblestones. Homer Williams partnered with Paige Powell, Portland doyen and one-time Warhol Factory member, to start a private art foundation to sprinkle sculpture throughout the neighborhood. The first (and only) piece: ’80s graffiti artist Kenny Scharf’s playfully bright “Tikitotemoniki Totems” in Jamison Square. Stefopoulos’s champion, James Harrison, even hatched a plan to resurrect the Lovejoy Columns in a large traffic island (price tag: $1.5 million). Sure, it was a stretch. But hey—office developer Gerding Edlen had just converted a refrigeration building nearby into an architecturally stunning new headquarters for the global creative firm Wieden & Kennedy. Powell was busy luring Maya Lin to propose a park, and Williams coaxed Frank Gehry into considering designing affordable housing for the district. In the end, those big names ended up doing nothing, but, at the time, anything seemed possible.

In the early 2000s, opening days for the neighborhood’s new condos were like parties, with lines around the block. “Flipping”—buying early and selling soon at major profits—became a sport. Backed by financier Peter Stott, Gerding Edlen bought the five-block old Blitz Weinhard Brewery for $19.5 million. They transformed it with the neighborhood’s first supermarket (Whole Foods, of course), its first Class A office building, and the first LEED Gold condo tower in the country. The adjoining 1891 armory became the nation’s first LEED Platinum theater and historic renovation.

“It was an incredible period,” recalls Solheim, often called the “father of the Pearl.” “Everyone was local. The developers, investors, architects, and contractors were on the street, figuring it out, building by building. We were competing. But we were also reinforcing.”

Timing is everything. When the Great Recession rolled in, unlike so many cities (or other Portland neighborhoods—say, South Waterfront), the Pearl had comparatively few condos left unsold. Stott and his partners nicely timed the sale of three Brewery blocks for a local record of $292 million—in 2007, moments before the economy’s wheels spun off. Even the Lovejoy Columns enjoyed a little of the boom’s final months: developer John Carroll installed two of them in a plaza adjoining his sold-out condo development, the Elizabeth.

For the Pearl as a whole, the recession was less a crash than a historical dividing line between “Early” and “Late.” The two eras share a common DNA of parks and streetcar and Portland’s compact 200-foot blocks. Beyond that, they are increasingly distant cousins.

In the Early Pearl, some “streets” became landscaped pedestrian corridors threaded between residential buildings. In a market hungry for condos, architects refined a template that, on the tiny blocks, maximized sunlight into every unit: essentially a six-story version of the courtyard apartment. Aging baby boomers and well-heeled Gen X creatives came in droves. Writing in the Oregonian at the time, I noted that the developers had nicknamed the monoculture of buildings “the Pentagon,” and I raised doubts about failure to focus retail on single corridors to create more urban energy. But with 15 years of hindsight, I now think those buildings offer lovely, neutral backdrops to the lush gardens and tree-lined streets. The scattered retail creates a charming sense of discovery, like Parisian side streets. The Early Pearl is essentially a garden district, with a graceful coherence as distinct as the hexagonal apartment blocks of Barcelona’s Eixample district.

Stretching north of NW Pettygrove, the Late Pearl is rising in a different form. Gone are the green streets. The shorter buildings have grown bloated, the courtyards more pinched. Towers are rising, skinned in reflective glass. All but one of the new buildings recently finished or under way are rental apartments, meaning the residents (and in many cases, the developers) won’t be there for long. Retail has become more lonely than charming. Long envisioned as a chance to add some historical texture to the district’s gleaming newness, Centennial Mill has sadly been neglected by its owner, the PDC. With redevelopment plans stalled, parts of its decaying carcass will continue to be demolished this year.

Asked whether there were gods, Diogenes replied, “I do not know; only there ought to be gods.” The same might be said of city planners.

Stefopoulos’s portrayal of the philosopher now sits on a concrete column crowned by remnant rebar—a “place you should know about” for many organized history tours. The Pearl District, by most measures, particularly those of similar urban redevelopments of other American cities, is an enviable success. Since 1991, the district has gained more than 9,000 housing units. Hoyt Street Properties, thus far, has built 150 housing units per acre. But as in other cities, affordability is a problem. The first new condo building to rise since the crash is 80 percent sold, at an average $700 per square foot. Thus far, developers and the city have fallen short of the 30 percent affordability goal by 123 units.

On a recent summer evening, I walked the Pearl with the 1983 “Last Place in Downtown” study in hand. Most of the plan’s drawings of expansive office parks missed the future, by a lot. But NW 13th Avenue unfolded in renovated historic buildings with shops and restaurants spilling out on their loading docks and pedestrians freely walking in the street—just like the picture. Hopefully, the Late Pearl’s patina will mature to match its older cousin’s, and the dealmakers and architects who shape the old US Postal Service’s 12 blocks will plan and draw pictures—but also work it out, competing and reinforcing, on the ground.