Time Slip: Photographing Drag Races at Portland International Raceway

Veteran local photographer William Anthony spent much of summer 2016 documenting the Wednesday-night drag races at Portland International Raceway, where drivers run the one-eighth-mile track in every kind of vehicle. Anthony discovered a scene bonded by competition, certainly, but also community and a love of cars often shared across generations. There’s some serious speed, too—“a rich mix of gasoline and adrenaline,” as he says. Here’s Anthony’s telling of the story behind the resulting photo series, Time Slip. (Find more work on Instagram.)

I first took my cameras out to Portland International Raceway for the Beaches Cruise-In car show—a fellow photographer took me out there. I had just purchased an old vintage camera and wanted to test it out, and the nice thing about a car show is that the cars don’t move—you can take a bunch of static pictures and test the lens and the camera functions.

While we were at Beaches, I could hear the drag racers in the background. Before I knew it, I was wandering through the pits. Wednesday nights are a National Hot Rod Association event, and they have an open-pit policy. You can literally walk into the pits and talk to the drivers and the crews. On Wednesdays it’s grandpas and grandsons—it’s very community oriented, very mellow. You could often walk up and shake hands with someone and ask about a carburetor, or a paint color, because car people love talking about their cars.

For someone who has a camera around his neck and a million questions in his head, it was perfect.

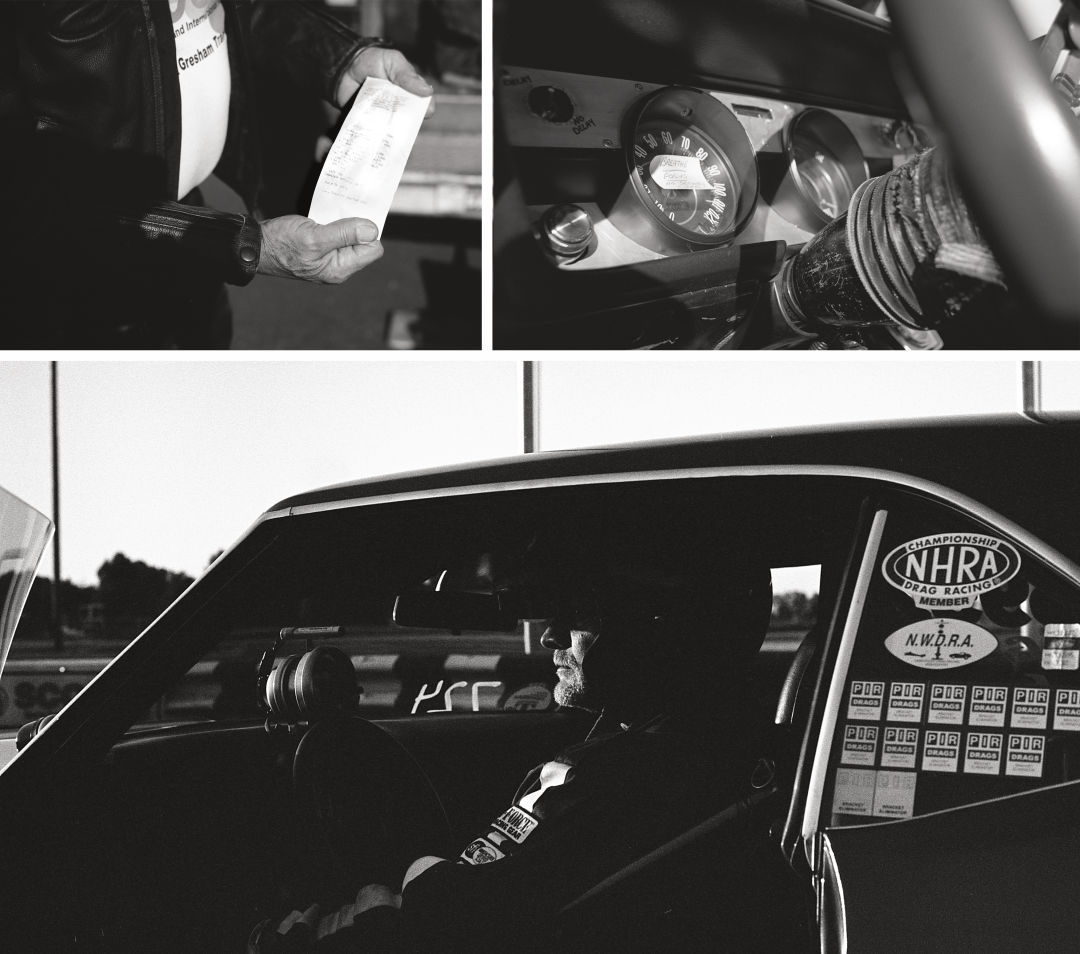

Clockwise from top left: a time slip recording a driver's performance; an inspirational dashboard Post-it; driver Greg Kielman

Image: William Anthony

I soon recognized that Wednesday brings out the same group of people over and over again. It’s their bowling night. They come week after week. The race format is called “elapsed time bracket”—an elimination tournament, set up like March Madness, with competitors weeding each other out little by little. The interesting thing is that they don’t race against each other head to head—you think of drag racing as someone waving a flag and two cars taking off, first to the line wins. On Wednesday nights, drivers race against their own estimated time. They write what they think they’re going to do on the eighth of a mile. If they go faster, they’re out of the tournament. They're striving to perfect their reaction time. (It’s a little hard to wrap your head around.)

I immediately met a couple of people who were integral to introducing me to the community, in particular a guy named Ed Peters, a former US Air Force recruiter and a good talker. He became my Rosetta Stone to the whole scene. By and large, it’s a blue-collar crowd—there’s a truck with “Carpentry” on the side, and you pop the back open and there’s a dragster inside. A lot of folks have been doing this since childhood. Generations race together.

There’s a junior class, these amazing little two-stroke dragsters that kids race—for those kids, this is Little League. There are muscle cars, alcohol burners, “sportsman” class, and “stock,” which basically means anything. I’ve seen guys drive in off the streets, take the regular wheels off their cars, put their racing slicks on, then race. I’ve seen Subarus out there. One guy shows up every week in a kind of Sanford and Son truck.

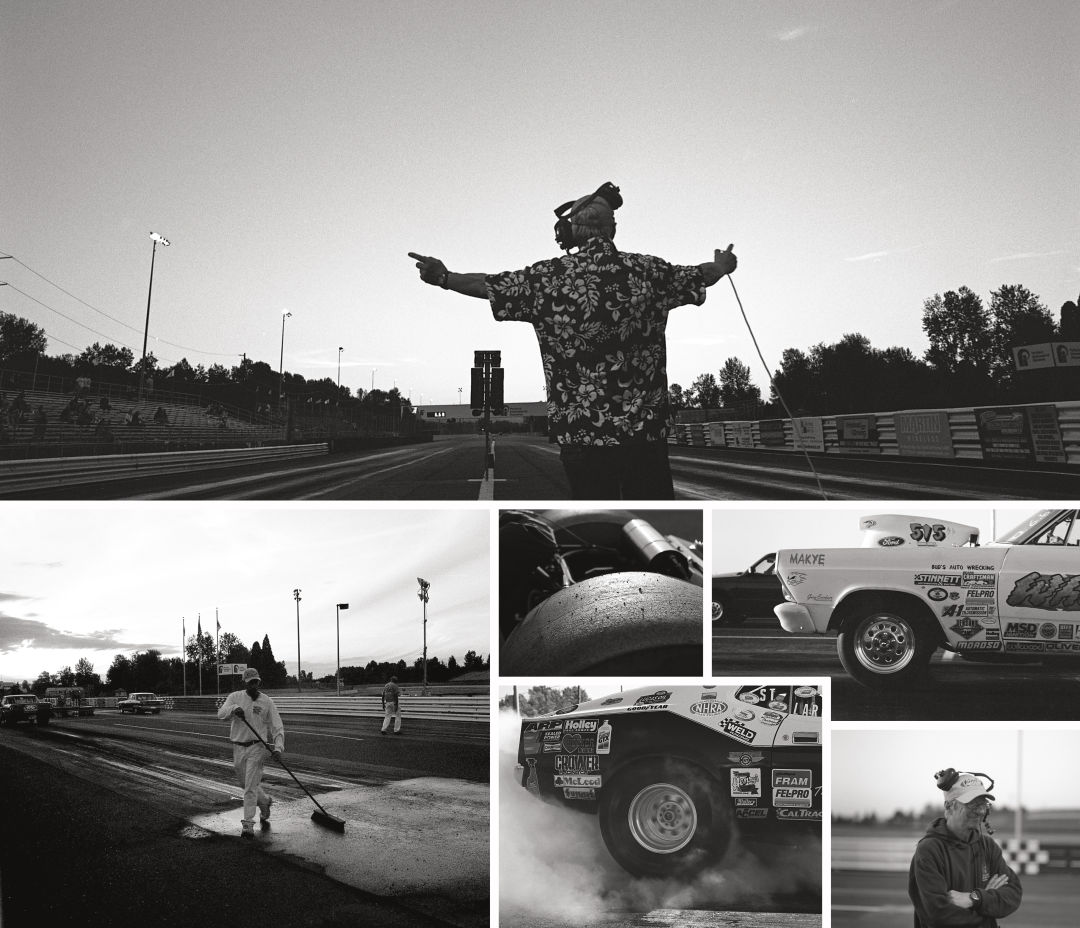

Clockwise from top: Starter Jim Vaughn calls dragsters to the starting beam; cars at the starting line; veteran PIR starter Jim Vaughn; specialized "drag slick" tires; sweeping the "burnout box"

Image: William Anthony

It’s more social than competitive, but there’s a core of drivers who are consistently competitive, and they are the ones who win. If you had the entrance fee, you could race on Wednesday nights. It’s open mic night. You might not win, you might get humiliated, but you could do it.

My initial impression of the people was that we just had a love of cars in common. And that ended up becoming a kind of theme for this project. I know it sounds trite, but it’s true—working on this has changed me on some level. I went in with preconceived notions about this community. And I’ve walked out with some of them being confirmed, but most of the experience has been enlightening to me.

It’s a relatively conservative crowd. Any time you deal with automotive stuff, for some reason, that seems to be the case. But I tried to find what we have in common. I love cars. I love the passion of doing something as intensely as they do. And because I was shooting with analog cameras—I had my Leica M3, which is from 1961 and has no light meter and no electronics, and my Canon AE-1, which was my first camera ever, and a Rolleiflex that I used for portraits, which is also all mechanical—this wrench-turning community immediately took to it. They respected that I was doing it the hard way—a very manual way. They’re driving vehicles that have all nonessential equipment stripped off of them. If something breaks, they have to fix it.

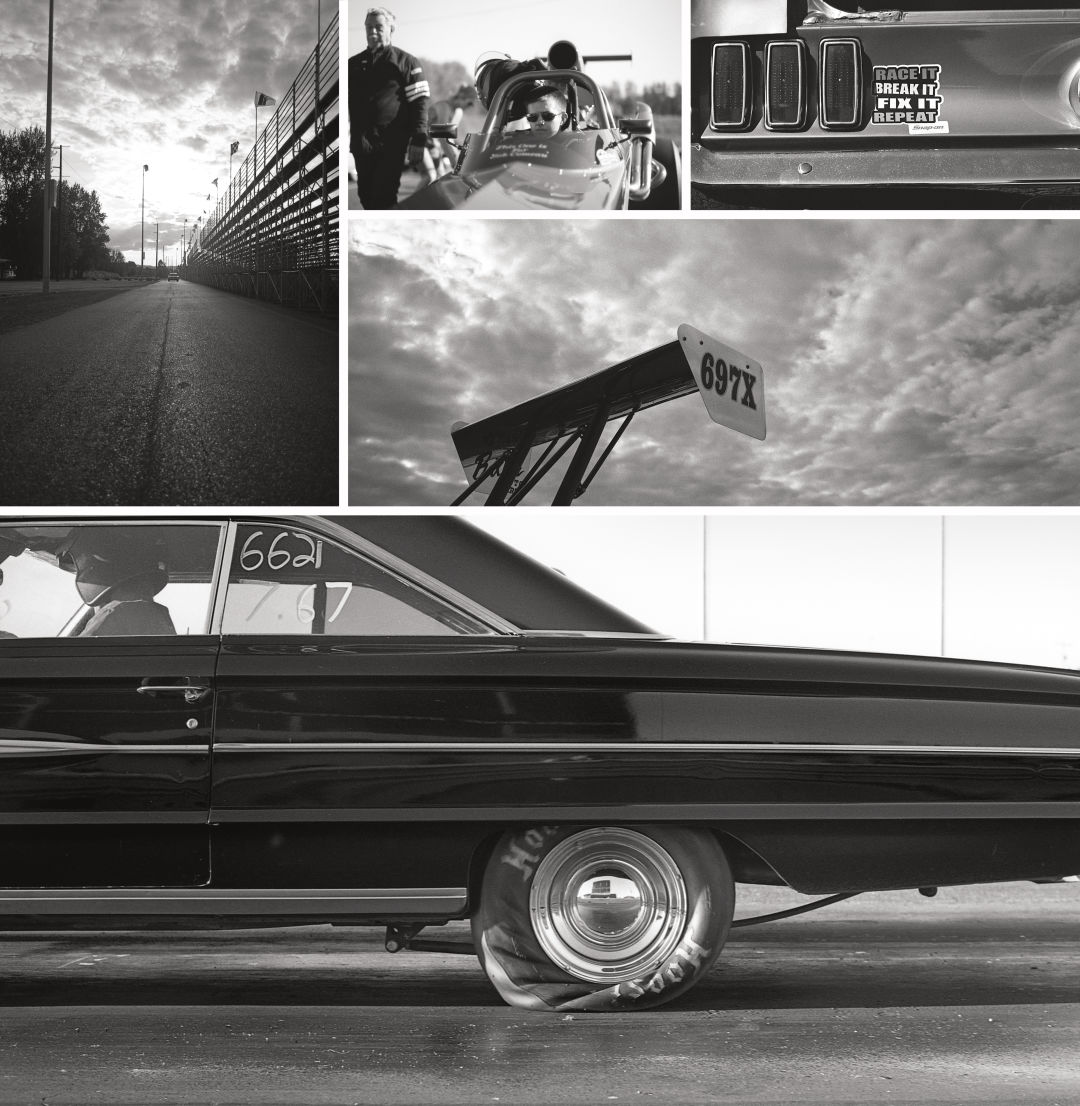

Clockwise from top left: The "return road" via which cars return to the pits; JD Cross walks past driver Charlie Dietrich; driver James Heriford tests his "wrinkle wall" tires

Image: William Anthony

Shooting all analog with black-and-white film put a different patina on the images and, in a way, brought me back to my roots. I think restrictions are good for creativity. I didn’t want to shoot drag racing like everyone else does. When I got there, there were five other guys, with modern DSLR lenses and monopods.

So I went the other direction and gave myself the quick-fire challenge—three ingredients and 15 minutes: black-and-white film, two film stocks. Your iPhone can shoot in almost complete darkness and things look pretty good. When you commit yourself to 400-speed film, that’s a challenge. You’re not going to shoot in really low light.

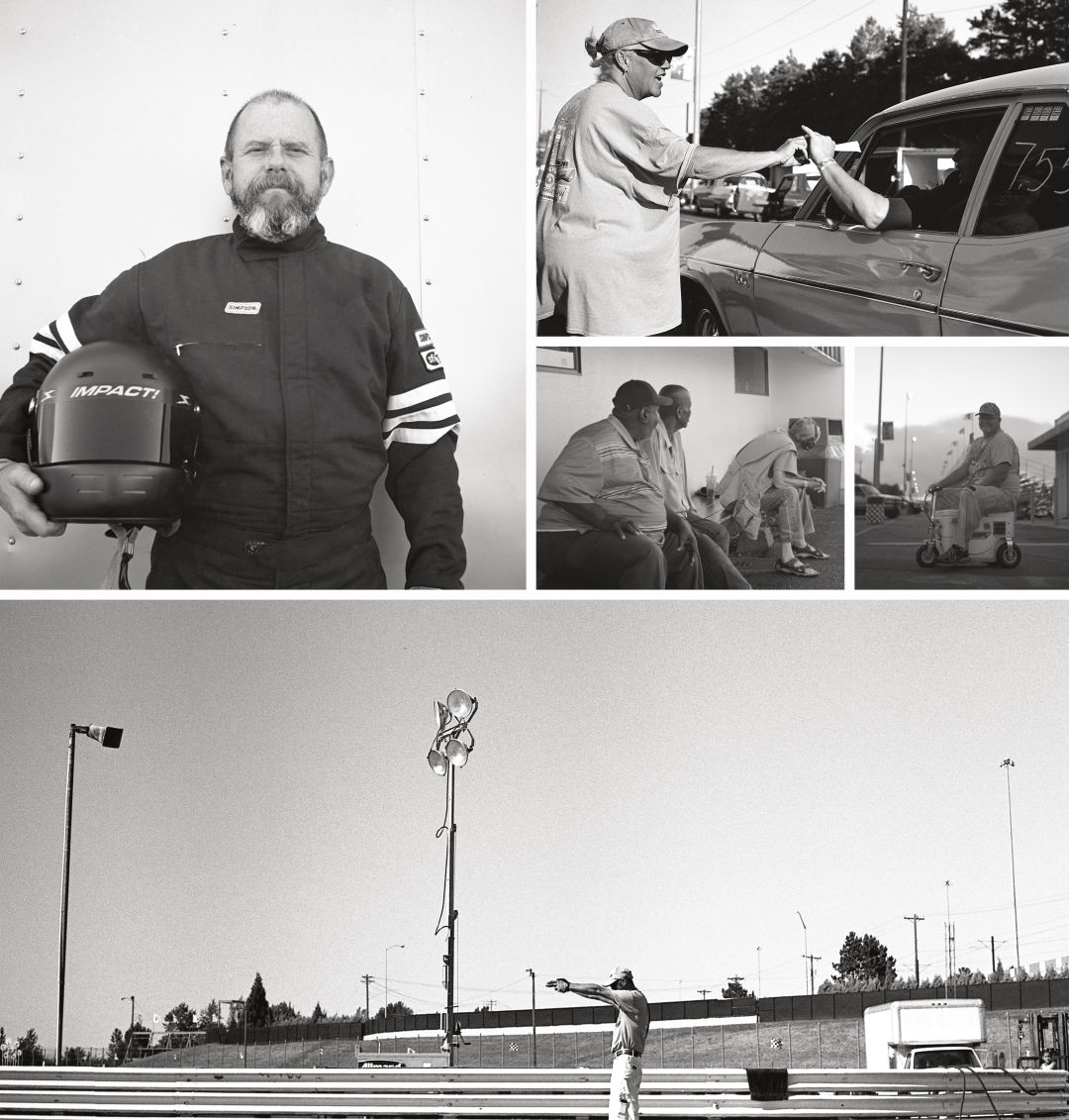

Clockwise from top left: Driver Ed Peters; Cathy Frasier hands a driver a time slip; driver Harry Cole on his electric beer cooler scooter; fans watch the dragsters; signaling for speed

Image: William Anthony

I didn’t want the series to be about the flashiness of the paint jobs and the stickers. Every driver tries to make their car stand out. Some cars look like old suitcases covered in travel badges. Shooting in black-and-white, what comes to the fore is the intensity of the racing, people getting into the zone, but also a documentary of the humanity behind it. Most of these cars are older than I am, and they’ve been personalized by every owner. I could literally go to one car and spend an entire day just shooting the tiny details—the Post-it notes on the speedometers, the scratches on the windows.

It was all worth it when I showed the work to the drivers, and having them thank me for seeing what others weren’t seeing.

Clockwise from top left: Dave Fountain and his old Ford step-side truck; Brian Overturf and a young fan; the public viewing area; race official Jack Russell enveloped by smoke in the burnout box; Charlie Dietrich in his Super Pro dragster; EMT Anthony Chavez

Image: William Anthony

Development and the shifting demographics in North Portland are putting new pressure on PIR, and there’s an awareness problem—people just don’t know that it exists. The future of this community is anyone’s guess.

Another advantage of shooting in black-and-white: in some shots, you have no idea what era this is. The cars are right out of the ’70s; the drivers look like they’re out of the ’70s. I decided to call the series Time Slip because the little pieces of paper on which drivers’ race times are recorded are called time slips, and every visit feels like a little fold in the space-time continuum.