Can a New Portland Museum Save Chinatown’s History?

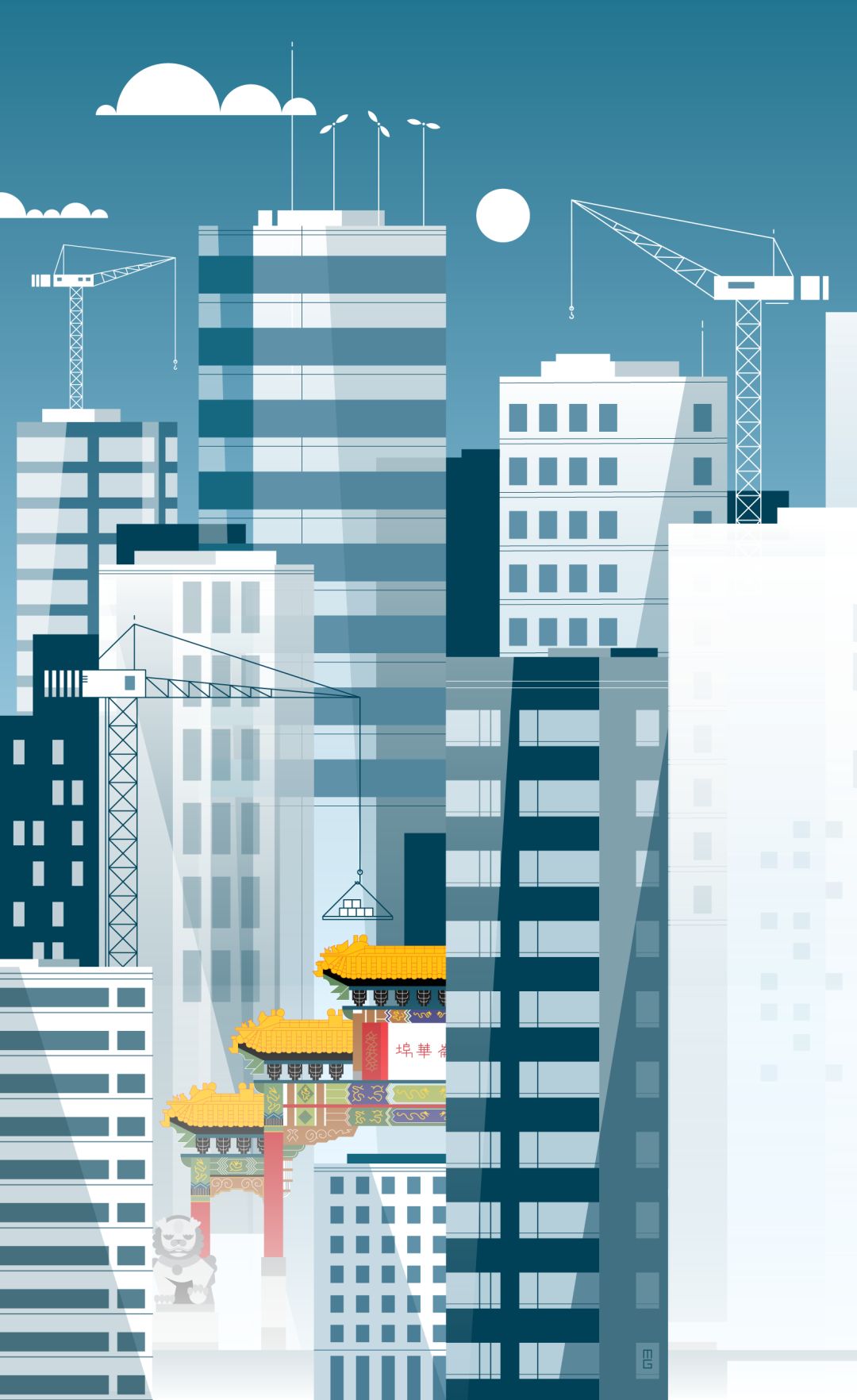

Image: Martin Gee

Even at 86, Gloria Wong is still discovering things about herself, and Portland.

Wong remembers visiting her father at Fong Chong Grocery, where he worked in the 1930s heyday of New Chinatown north of West Burnside. (Old Chinatown, south of Burnside, was forced north during an early-century population boom.) She knew the neighborhood as a friendly and lively place, home to Chinese Americans, African Americans, Japanese Americans, and Greek Americans. She did not know that in 1866, her maternal grandmother was the first documented Chinese American born in Portland. Wong discovered that fact only recently, from a 1906 affidavit that had been intended to challenge her own mother’s citizenship. “The older generation didn’t talk about how they grew up,” she says.

During the 1890s, Portland had the second-largest Chinatown in the United States. Today, its history stands in danger of disappearing altogether. While the iconic Hung Far Low sign, Fourth Avenue gate, and Lan Su Chinese Garden remain, the crackling neon signs of cherished dim sum restaurants have dimmed; family-owned grocery stores like Fong Chong are no more. According to Wong, from the beginning many Chinese immigrants viewed their buzzy downtown neighborhood as a ghetto. As soon as they could, families would leave for other parts of the city.

“The thing is, you worked so hard to get out of Chinatown that you really didn’t want to move back,” says Wong, who grew up in Ladd’s Addition herself.

In a neighborhood once filled with Chinese Americans—in 1900, they accounted for about 9 percent of the city’s population—a combination of neglect, an influx of social services for drug addiction and homelessness, and sporadic new developments transformed the neighborhood into a no-man’s land in search of an identity. Offices, apartment complexes, and the much-derided “Entertainment District” increasingly obscure the remaining landmarks. The danger: an area with deep links to the history of Portland and the West Coast could become a fringe of the Pearl.

“It’s not just the history of the Chinese; it’s the history of Portland’s development,” says Terry Chung, founding president of the Portland Chinatown History Foundation.

Opening in early 2018, the Portland Chinatown Museum aims to preserve at least some heritage by foregrounding stories of the city’s Chinese immigrants. After the Oregon Historical Society debuted its Beyond the Gate exhibit last spring, the new museum’s founders located a more permanent home with the help of 10 primary donors. They leased a single-story flat-roofed brick structure at NW Davis Street and Third Avenue, a polestar for the neighborhood’s polyglot communities, once home to a procession of restaurants, barbershops, dry goods stores, second-hand stores, and laundries. The 6,500-square-foot museum will focus on stories of the early Chinese immigrant experience, aided by visual installations from Portland artists Carey Wong and Rose Bond. The space will also provide a venue for rotating exhibits from local and regional Chinese American artists, including interdisciplinary artist Horatio Law and Seattle-born photographer Dean Wong. The museum plans a future expansion that would add long-term student housing.

“It is a way to engage the larger Asian community about the neighborhood’s changes and what it means to keep your culture and your language,” says historian Jackie Peterson-Loomis, one of the project’s leaders.

While development shows no signs of slowing—Prosper Portland’s five-year action plan for Old Town/Chinatown calls for significant new investment—the museum’s founders hope their efforts will open an inclusive, multicultural dialogue about Portland’s past.

“For a city that’s been dubbed ‘the whitest city in America,’ telling the history of this multiethnic neighborhood is important because it gives agency to these marginalized groups of people,” says the museum’s assistant director, Jennifer Fang.

Adds Chung: “This project is something that I want to see happen not only for myself, but also for my parents’ generation, and for future generations so they have a sense of who they are and where they came from.”