A Portland Journalist's New Book Ventures into Silicon Valley's Dark Side

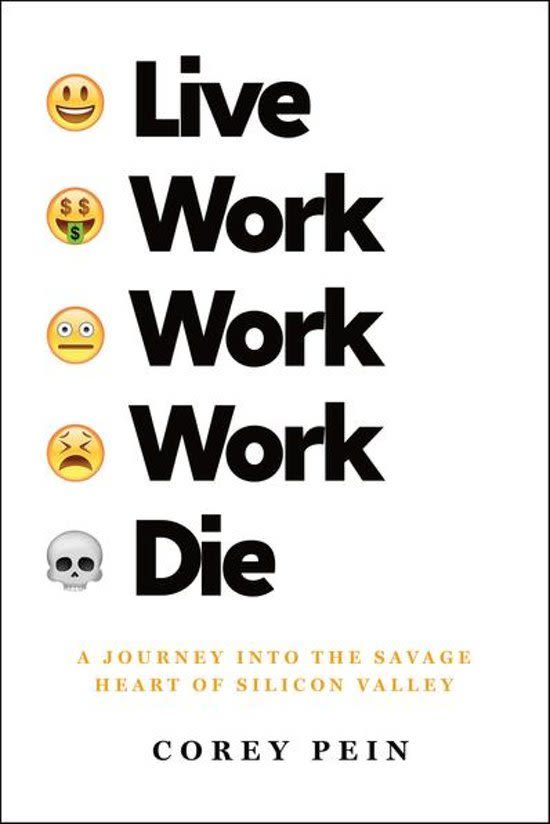

Corey Pein didn’t always distrust the digital. The author and former Willamette Week reporter, 36, grew up tinkering with code and helping friends troubleshoot computer problems. But after much blood, sweat, and toil at two doomed start-up ventures—a digital news site and a photojournalism database—Pein decided to report firsthand from the tech industry’s great California capital. What makes Silicon Valley tick? What draws people there? And, most important, what is this powerful force doing for (or to) humanity? Pein’s book, Live Work Work Work Die: A Journey into the Savage Heart of Silicon Valley, published this spring, documents a sprawling dystopia of shabby living conditions, casual fascism, and a deeply unhappy workforce. We sat down with the journalist to find out what he learned.

After two start-up flameouts, why move to Silicon Valley?

Tech is a subculture that prizes failing, right? The idea was, I’ve never failed in Silicon Valley, so I should go there and try.

Image: Courtesy Corey Pein

Your book chronicles your journey along the tech industry’s fringes: the awkward parties, the investor pitch meetings, the overhyped conferences that swirl around success stories like Google and Apple. Notably, your reporting features several passages about slum-like Airbnbs: group houses packed with tech industry hopefuls. (See excerpt, below.) Is that really how people live?

It’s so hard to break into the San Francisco housing market. I’d stay in these places with anywhere between eight and 20 people, mostly men, in a habitation designed for three or four, sleeping in bunks. In one place, I had a private room, but there were two bathrooms for more than 20 people. I mean, not up to code. A family of three would share one room—recent immigrants, it seemed to me. The next room would be me; the next, a Google intern.

So residents were, you could say, fresh off the boat.

There are a lot of what I call Internet Okies. The economic growth is in tech, so you pull up stakes and move to where the tech industry is. The result is just constant precarity. Not just in housing—in everything.

Did you expect it would be like this?

I knew the Valley proper would be suburban sprawl. San Francisco, I was fuzzier about, and in Portland, people would say, “Oh, you’ll love San Francisco.” I found the opposite. I mean, I guess I would have loved San Francisco 20 years ago.

Whom did you meet?

A mixed demographic, but only in certain ways. I didn’t see a lot of black people on the circuit. There were South Asians, East Asians, and white people. That ties into a new sort of reactionary politics—this new kind of Silicon Valley racism. It’s centered around these eugenics-like ideas: like, Chinese people are smarter just by virtue of their genes. You hear things very much like what railroad barons used to say about their labor force.

Pein’s book paints a grim picture of the tech industry’s effect on America’s culture and economy. In particular, he criticizes the philosophy that underlies many tech success stories.

You write about a lot of “disruptive” companies, à la Uber. What did you learn?

To paraphrase a union official I interviewed, the model is to push the cost of doing business onto the user or the worker. If you’re Uber, it’s your drivers—you call them independent contractors. If you’re Facebook or Twitter, it’s all of us. All of us on Twitter are basically writing for Twitter, for free. The users and workers create these companies’ value, and don’t get a piece of it.

TaskRabbit [a one-gig-at-a-time freelance connection service] was big in San Francisco. The no. 1 TaskRabbit job, when I was there, was standing in line for restaurants. You can totally see that taking off in Portland, right? This all requires almost a caste system, with involuntary entrepreneurs at the bottom. Elon Musk recently called them “barnacles.” So you have the whales, with their $200,000-a-year entry-level salaries, and you have the barnacle, who’s standing in line for them at Screen Door.

In Oregon, we often look to tech for economic salvation. What’s your perspective?

Realistically, we’re sandwiched between Seattle and San Francisco. We’re not going to compete with them on new companies or the workforce to feed them. The only thing we’ll compete with them on is housing price. That’s our relationship to the tech industry. We’re not going to be Silicon Valley 2, or anything like that. And would we want to be? Look at what Amazon has done to Seattle. It’s basically a company town now.

Portland has so many great things to offer. If we trade it for a bit part in a tech bubble, it’s an embarrassment to our collective leadership and imagination. One thing Oregonians have to offer over people from California and Washington—and I’m from Washington—is a healthy skepticism. I’d like to see that on display a little more when it comes to the tech industry.

A lot of people in Portland’s start-up scene are concerned with ethics, mission, and values. Do you think that ethos could change the industry?

I suppose it may be genuine in specific cases. But, generally, for the industry? No. It’s really hard to make money online unless you’re ripping someone off, or commodifying something that was once free. VCs [venture capitalists] are looking for ideas with revenue potential. Usually that means finding another industry to destroy.

There’s not much actual coding in the book. Do people need to know about ... computers?

Technical skill is definitely the last thing anyone looks at. Marketing is always first. Coding is important if you’re trying to get hired as a back-end developer, but even then, people bluff their way through. There’s a lot of online forum material about how to beat coding interviews—how to get that sweet job at Google or Facebook. There’s more copy-and-paste than people realize or want to admit.

Is coding a good career path? It’s touted as such.

I think it’s a difficult and painful job for a lot of people. The happiest people I met in Silicon Valley had boring, steady engineering gigs at old-line, Intel-type companies, clocking in and clocking out, like a job at Ford or GM back in the day. It’s the young people—going to hackathons and consuming nothing but Mountain Dew for three days so they can bang out a product and impress investors who are going to exploit them—who are really miserable.

Image: Amy Martin

Pein embedded in the Silicon Valley scene before the 2016 election and later revelations about Russian-funded social media advertising, Cambridge Analytica data harvesting, etc. Even then, he discovered much that troubled him about tech’s political tendencies and larger ambitions.

You write about right-wing, libertarian, even fascist politics bubbling up in the Valley—what did you find?

Mainly a lot of casual misogyny. I’m not breaking any news there. You also run into a lot of ideas about racial discrepancies. A lot of people in Silicon Valley really believe that libertarian capitalism is the natural order. Even a lot of people who call themselves liberals. What they really mean is they’re for gay marriage and legal weed.

Looking back post-2016, we can now see that social media was politically manipulated in all sorts of ways. What did you make of Mark Zuckerberg’s recent trip to Congress, for example?

He got off easy. I’ve never worked for any newspaper, magazine, book publisher, or broadcaster that would allow Nazi propaganda, even in ads. I really don’t think you’d have burning swastikas and torchlight rallies in American cities without Google, Facebook, and Twitter. The tech companies have an idea of free speech that takes all responsibility away from them. They did have a responsibility, and they blew it.

But it’s not just Facebook, right?

Sam Altman, one of the founders of [venture capital firm] Y Combinator, published an essay not too long ago about how the Bay Area has gotten too stifling. There’s no free speech here, he said, and where the real freedom in the world is now in places like China.

What could China offer US tech companies?

This might sound crazy, but my best guess is they want to do gene editing and brain-machine interface experiments. The only “free speech” China allows is experimenting on human embryos. I mean, that’s it. Google’s 23andMe [the at-home ancestry service] encourages genetic screening when there’s no compelling need. They want to normalize it. But if you give your DNA to Google, do they own your genetic code? It’s on their servers. That’s not sorted out yet. When companies talk about wanting space free of regulation, we should be very concerned.

Where might all this lead?

Somebody at MIT Media Lab came up with this thing that fits on your head and can read your mind. If you’re concentrating and thinking of a sentence or something, it’ll pick that up and translate it. The founders of Google have said since the beginning that they want to get Google inside your head. That seems very problematic and troubling. People don’t even want to believe it, but it’s there. They’ve been working on this stuff for a long time. And now Facebook is getting into dating apps—that should really concern people. They already know everything about you, your friends, and they’re building a profile of your personality and your habits. And now they want to suggest to you who you might hook up with?

Image: Amy Martin and Courtesy Northpix/Shutterstock

Pein’s conclusion? That the Internet, created by public agencies, has been hijacked for private profit—and that the people should take it back.

Is there any solution?

We’re in a bind. I don’t think there are technological solutions—primarily political solutions. People should do old-fashioned stuff, like call their congresspeople and ask what they’re doing about personal data protection, the proliferation of hate speech, the abuses of the gig economy. If that doesn’t work, take to the streets. I could foresee pickets at Facebook and Google. We should definitely look at new networking protocols that stay under public control.

What about your own use of technology? You’re still on Twitter, for example.

I just got a dumbphone, because, really, I have no self-control. The constant notifications were disrupting my ability to think and, like, enjoy my day. I’m conscious now of the addictive qualities of these platforms. I’d really like to travel back in time to 2002, I guess. When my friends hadn’t disappeared into this Facebook version of my friends, whom I rarely see in real life. It’s perverse, how we’re all sort of forced to become phony advertising versions of ourselves on this service, and we don’t even profit from it.

I think we’re all struggling, on a personal level, with what technology has done to our lives, and don’t really know how to talk about it. I guess the book has been my way of dealing with it.

Image: Courtesy Macmillan

An excerpt from Live Work Work Work Die

Lacking the financial stability required to secure a lease in San Francisco, my best hope was to find a “hacker house,” the product of disruptive innovation in urban real estate. The city was once riddled with small apartments and single-family homes that sheltered trifling handfuls of obsolete laborers and their unproductive children, often for decades at a stretch. But the tech boom let such so-called “family homes” reach their full potential as investment properties.

I had my eye on one special property in the Mission District. It was called 20Mission, and it had been designated San Francisco’s “best hacker hostel” in 2014 by local alternative newspaper SF Weekly, which reported that it had been founded by a “Bitcoin trader and entrepreneur.” It turned out 20Mission was so central to the San Francisco cryptocurrency scene that a blog nicknamed it Bitcoin’s Hogwarts.The website featured an array of appealing photographs. There was a sun-bathed deck covered in bright green AstroTurf and furnished with a large gas barbecue grill; a spotless, spacious lounge with an inviting plush leather couch; a hopping party in a high-ceilinged space; a rooftop yoga session; and a tidy, funkily furnished bedroom complete with a double-sized futon and hammock. I composed a flattering self-introduction and announced my interest in joining the 20Mission community. Soon enough, the manager, Steven Lombardi, replied with an invitation to “come by and chat.” It felt like a job interview.

In the meantime, I read up on the history of the city’s best hacker house. The neighbors, it seemed, were not thrilled. On the night before Halloween—which coincided with a World Series victory by the San Francisco Giants—riots had broken out around the city. In the Mission, windows were smashed and fires set, and 20Mission was besieged by an angry mob that threw garbage and bottles at the building and chanted “Techies! Techies!” The techies, for their part, seemed unperturbed. “We are the architects of the future!” one 20Mission resident proclaimed to a reporter.

When the day came for my appointment with Steven, I saw that the architecture of the future had its windows soaped over and its doors sealed shut. As it turned out, city code enforcers had shut down 20Mission’s vaunted coworking space over a lack of proper permits. I found another entrance around the side.

The place looked smaller than it had in the publicity photos—dumpier, too. The flooring wasn’t AstroTurf, as I thought, just a dirty length of wrinkled green carpet. The hallways were dark, but I could see that walls and doors were covered in posters and decals, like a student dorm. The smell of pot smoke permeated every corner. As I passed each door, I received an auditory tour of the private spaces inside—a little electronica in one room, a little orgasmic moaning in the next.

Stocky, dome-headed, and brusque, Steven led me on a perfunctory tour. The entire house, all forty-one units, shared two coed bathrooms. Small rooms—very small—cost $1,400 per month; mediums, $1,600; and the largest, $1,800—“just like McDonald’s,” he said. My face must have betrayed my honest reaction. Steven sensed my reticence. He said there were twelve or thirteen ahead of me on the waiting list, all ready to make long-term commitments and put up cash (or Bitcoin). “I’d prefer someone who stays at least six months. It makes my life easier. Nothing personal,” Stephen said. With that, he was gone, along with my hopes of moving into the city’s best Bitcoin playpen.