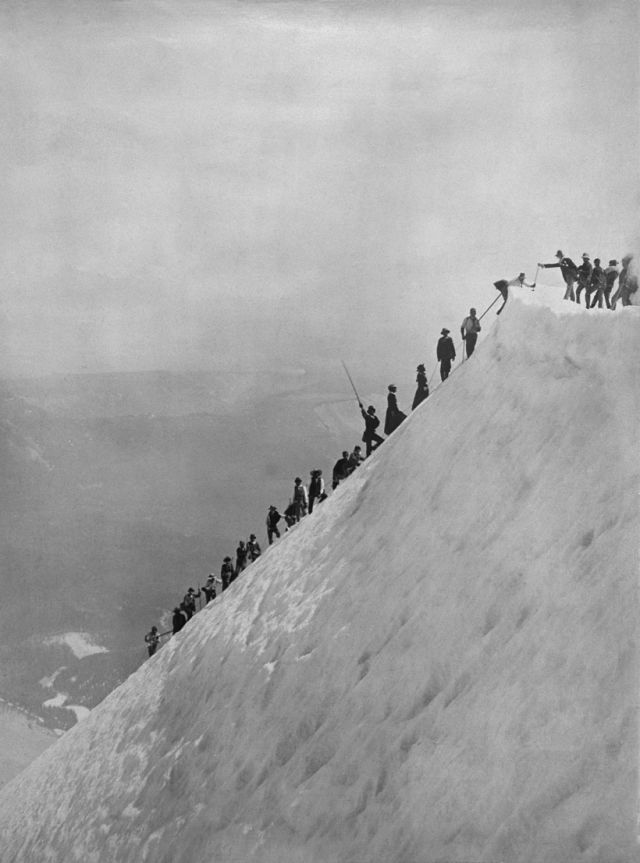

125 Years Ago, Hundreds of Climbers Undertook a Mass Ascent of Mount Hood

Hood's OG peak baggers, sporting burnt cork sunscreen and wooden alpenstocks

Image: Courtesy the Mazamas

At 2 a.m. on July 19, 1894, a bugle sounded “Reveille” on the slopes of Mount Hood. Around 300 hardy souls, who’d spent the cold night at tree line above Government Camp, shook off their blankets, built campfires, brewed coffee, and shared cans of corned beef. “All was bustle and excitement,” one group member, a 17-year-old named Frank Branch Riley, later wrote. By 3 a.m., the sky still dark, they began their march to the summit.

This wasn’t Hood’s first ascent, but it certainly enjoyed the most ballyhoo. A month prior, ads in the Oregonian and other Northwest newspapers called all “mountain-climbers and lovers of nature” to gather for a mass ascent would launch the Mazamas as one of America's earliest alpine societies. The climbers—many of whom would become Mazamas charter members—traveled to Oregon's highest peak by horse or mule or foot. An “old-fashioned bean-bake” was promised; at least one trekker brought a cornet.

Making the final summit push

Image: Courtesy the Mazamas

The climb itself was a long, strenuous plod in tempestuous weather. Shortly before sunrise, Riley’s party saw a blizzard roiling below. “It was like looking down on an embryo world frightened with the conduct of a baby storm,” he wrote. “We could see the lightening [sic] part the canopy of clouds and the thunder following would come to us faintly.” That blizzard soon engulfed the climbers. Fay Fuller, one of several dozen women on the ascent (and the club’s first historian), described its sudden arrival: “There was furious snow mixed with hail; while the piercing cold wind blew so strong as to make it necessary to hug the rocks closely, to escape being blown away.”

Nearly a hundred climbers turned back; most pushed on. Around 8 a.m., the first party made it to the top. “From then until half past two, straggling parties kept reaching the summit, on which there were at one point more than 50 persons,” Fuller wrote. All told, 155 men and 38 women stood at 11,250 feet that day, where, according to Riley, they feasted upon “flounder in snow-bank,” “snow-ball croquettes,” and “snow-crust pudding.” To announce their triumph, the summiteers released several carrier pigeons bearing lists of names under their tail feathers. One bird named Pickwick, the Oregonian reported, arrived in Portland the next day “so completely worn out that [he] was hardly able to stand.” (It’s unclear what became of Jane, Frances, and Grover.)

Another view atop Mount Hood

Image: Courtesy the Mazamas

One-hundred-twenty-five years later, summit selfies have supplanted carrier pigeons, and climbers smear on sunscreen rather than burnt cork.* The Mazamas society today tallies about 3,500 members, with Hood still exerting an irresistible draw for mountaineers. (Upward of 10,000 attempting its summit each year.) And while modern Portlanders, unlike our 1894 counterparts, don’t cluster on rooftops with telescopes hoping to glimpse climbers, Hood remains that same snowy symbol of aspiration, prompting us on clear days to shout: “The mountain is out!”

*There was also a terrible application of burnt cork: blackface, a practice that even found its way to a pre-climb feast at Government Camp.