Is Oregon Addicted to the Lottery?

The cashier at Ray’s Food Place in Jacksonville knows the man with the white Fu Manchu ’stache buying scratch-it tickets. Hope Brown comes into the grocery store a couple times a week, trying his hand at whatever big lottery draw is scrolling by on the ticker.

Right now, at 10 a.m. on a Thursday, it’s just Hope in this corner, feeding money into the squat box between the birthday cards and booze. But when the draw gets huge—like last July, when the Powerball jackpot topped $150 million, the line at Ray’s can stretch out the door.

“It’s like flirting with religion,” Hope says. He’s been playing the Lottery since “the beginning”—by which he means the early 1980s, when Pacific Northwest states got in on the game. “You got to play to win.”

For some, this is Oregon’s luckiest store in Oregon’s luckiest city. In Jacksonville, a onetime gold mining town five miles west of Medford, there are just a few places to play multistate draw games like Powerball, Mega Millions, and keno. One is the J’Ville Tavern—the Rogue Valley’s oldest watering hole, with a rifle above the bar and a slatted wood ceiling covered in crumpled dollar bills. This is where, last year, local Reggie Pearne bought the ticket he found himself staring at past 1 a.m., realizing he was a million dollars richer.

But if you want to win big in Jacksonville, playing at Ray’s Food Place is the retail equivalent of asking a slinky dame to bless your dice. In 2006, a couple visiting from Whidbey Island threw down $100 at Ray’s and landed a $7.4 million winning Megabucks ticket. (Branded “Oregon’s Game,” our local draw game is a simple six-number “quick pick.”) Then there was the week of the October 19, 2005, drawing. That’s when a local couple, the Zitzners, bought a sheaf of Powerball tickets here and won $853,000—the very same day a Medford family also shopping at Ray’s took the national jackpot: $340 million, then the biggest pot in American history.

Ray's Food Place in Jacksonville, also known as "Jackpotville"

Image: Ramona DeNies

When Oregon Lottery official Patrick Johnson stopped by the J’Ville last January with the bar’s $10,000 “selling bonus” (winning retailers, too, get a piece of the action), he talked up the hype with the local NBC affiliate.

“We always joke around because when the Powerball gets high, we start watching Southern Oregon,” Johnson told KOBI-TV. “And I start looking for my hotel down here.”

Ray's sole scratch-it dispenser

Image: Ramona DeNies

Excitement is key to the Oregon Lottery’s dream machine. There’s suspense in wondering who'll hit the jackpot, and vicarious thrill, later, when winners hoist their big checks. At a time when corporations rapaciously data-mine personal transactions—from our location to social status and spending habits—the Oregon Lottery is still pretty analog: cash-based paper tickets and off-network video lottery machines tucked away in dive bars. (As of press time, the state legislature was considering a bill to let Lottery winners keep their anonymity even in the face of a public records request.)

It’s fun to scratch off foil with quarters or tap screens blinking with krakens and parrots. And if you agree with the Lottery’s understated but omnipresent marketing, it’s almost wholesome, underwriting everything from veteran services to Outdoor School.

But lest we forget, the sole job of the Lottery—a government agency—is to find new and creative ways to manipulate us out of our own money: $12 billion last year alone. It should be controversial, conditional. And yet, 34 years in, few seem to be asking: should we—could we—ever cash out?

State of Play

“Ah, Jackpotville.” Matt Shelby was running through bar charts and numbers from his windowless office in Salem, but now the Oregon Lottery spokesperson smiles, if a bit wryly.

“There is no such thing as a lucky retailer,” Shelby says. “All of the games are completely random. But because they’re completely random, sometimes you have anomalies, and a little town in Southern Oregon ends up selling a number of large winning tickets.” (It’s also a matter of volume: When a place gets a rep, Shelby says, more people buying tickets there “increases the likelihood that a winning ticket is sold at that place.”)

Shelby affirms a truth: players might sometimes beat the algorithm—a $60 win playing Cheeky Lil Devil, or a “life-changing” jackpot. But in organized gambling, from the Vegas Strip to the video lottery gauntlet in downtown Portland’s Virginia Café, the house always wins.

Ever since the Oregon Lottery was floated to voters in 1984 (sold to us by a Georgia scratch-it company as a bailout for our ailing economy), the agency hasn’t kept close tabs on players, or even how many are playing. But it does know exactly how much money we forfeit against some very long odds. In 2018, we spent a net $314 per Oregon adult on draw games and—unique to Oregon—video lottery. (Beyond video poker, Vegas-style slot games are something other states don’t offer outside of casinos.) And while prizes returned 91.2 percent of that to players, most will never break even, to say nothing of winning the Powerball jackpot. (The odds there are roughly 1 in 300 million.)

The house, meanwhile, is guaranteed a take—to the tune of $1.3 billion in 2018, of which $725,087,401 was transferred to the Oregon Legislature. That take is so reliable that the state routinely leverages Lottery revenue for long-term bonds. That means future lottery money backs loans for big projects like seismic upgrades and levees. (If ever the word “giddy” could be applied to an Oregon Treasury report, try its January 2019 lottery debt capacity update.)

Lottery revenue is just 5 percent of the state’s $24 billion total budget for the 2019–2021 biennium. But for Salem politicians, these dollars are gold—walking-around money, in a sense, as long as certain percentages flow into voter-approved buckets. (About half goes to schools, and a quarter to economic development, with smaller pots for state parks, watershed enhancement, Outdoor School, and veteran services. One percent is transferred to the Oregon Health Authority to administer free treatment for problem gamblers.)

“The General Fund and the Lottery combined, that’s the revenue that the Legislature has the most discretion over,” says Josh Lehner, an economist with the state’s Office of Economic Analysis. “They can spend it however they see fit.”

Lehner’s office produces quarterly Lottery revenue forecasts that are plugged into all sorts of budgets. It’s as though Lottery money were like any other state revenue source: our gas tax, income tax, business tax. And for some, the Lottery is a tax: a “regressive” tax. Critics (among them tax lawyers, academics, and a healthy cadre of Methodist ministers) argue that state lotteries cull the most money from their poorest residents: those most vulnerable to the lure of life-changing cash, and those most likely to see games of chance as more than casual entertainment.

Oregon Lottery headquarters in Salem

Image: Ramona DeNies

There’s tension baked into the idea of a state agency persuading taxpayers to give government even more of their money. To do so, most Oregon Lottery ads hype one of two messages: either hearts and minds (the Oregon Lottery “does good things”) or wallets (have some fun, you could win big!). But the temptation is always there to try less ... restrained marketing campaigns.

If you want a comedian to break down that tension, try a 2014 episode of Last Week Tonight, in which John Oliver lambastes the Pennsylvania Lottery for a television spot that played like “an ad for a mutual fund,” encouraging Mega Millions players to visualize multigenerational college funds. “Crucially, the lottery is not an investment,” said Oliver, “because it’s worth mentioning that those mega dreams are mega unlikely to happen.”

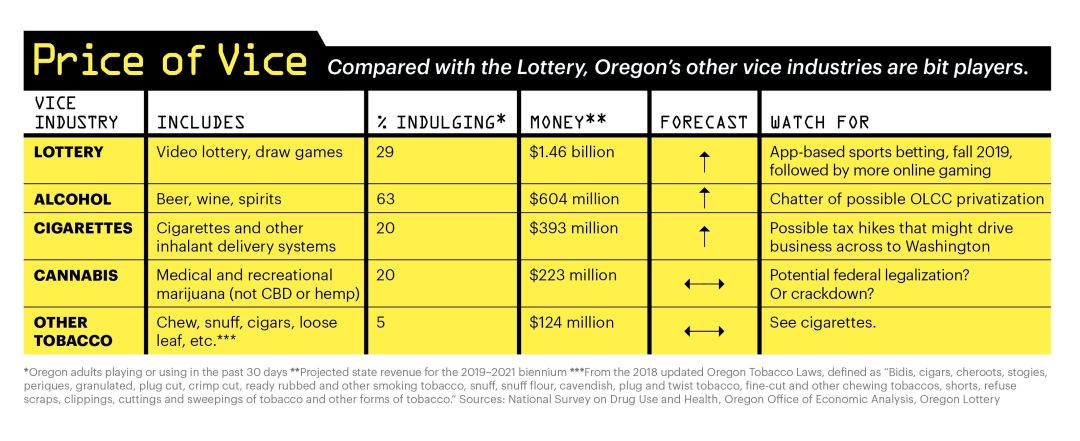

There’s an even more basic issue here: lotteries advertise. Gambling is considered a vice industry, much like drugs, booze, and prostitution: potentially destructive human activities we generally agree are here to stay. In Oregon, we’ve legalized some, and tasked the state to tax and regulate them. But you won’t see the Oregon Liquor Control Commission hawking schnapps and pot strains.

“Think about it this way,” said Oliver. “Gambling is a little like alcohol. Most people like it, some are addicted to it, and it’s not like the state can or should outlaw it altogether. But it would be strange if the state was in the liquor business, advertising it by claiming that every shot of vodka you drink helps schoolchildren learn.”

Another question we’re not asking? How far we’ll take it.Stranger still? In an era fueled by outrage, state-run gambling somehow chugs along without comment. There are hard questions here—like who literally pays for revenue shortfalls and corporate tax breaks. (Note that Oregon’s schools, despite all those decades of Lottery money, aren’t exactly flush.) Until we tackle them publicly, we’re operating in the moral gray. And we’ll be obligated to do so as long as the Lottery is leverage for our long-term debt.

Screen Time

“Some people, when we talk about mobile, get really concerned,” says Oregon Lottery spokesperson Shelby. “Other people ask, ‘Why has it taken this long?’ I have apps on my phone [to] buy just about anything in the world ... but I can’t buy a Lottery ticket.”

Shelby’s talking about the most dramatic change at the Oregon Lottery since the 1992 debut of video lottery (its biggest earner, bringing in some 70 percent of revenue). That development is sports betting—suddenly legal again at the state level, thanks to a 2018 US Supreme Court decision. And this time, the Lottery’s going online. Come NFL season this September, Shelby says, Oregonians with the Lottery’s new app will be able to wager on games from anywhere inside a statewide geofence.

“We’re a little late to the party, but we’re starting to catch up with customer demand in terms of mobile convenience,” Shelby says. The Oregon Lottery doesn’t move fast, and, in that, it likely resembles core players like Hope Brown: white, male, older, living near the I-5 corridor. At a 2017 legislative hearing, Lottery director Barry Pack shared recent, if vague, market research: “Our video lottery players generally represent the demographic population of Oregon—there’s no big, outstanding demographic difference.”

The Lottery’s data may be limited, but it’s clear its players are aging—as are the bars where they play. The Lottery maintains some 11,000 video lottery terminals, but lately, placing them in people-rich Portland is a challenge. Rising rents, Pack said, are forcing older metro-area dive bars to shutter; newer urban drinkeries are unable (or unwilling) to make space for the machines. Lehner, the state economist, says the Lottery is at a crossroads: if it can’t change up the game, it might lose its players.

“Right now, we know the baby boomers are [in] the peak gaming years,” Lehner says. “You have discretionary income ... and so you game to a larger degree than if you have little kids and you have to watch Nickelodeon all the time. [But] the millennials and the Gen Zs today, when they get older, will they game ... or choose other things, whether it’s just going to happy hour, breweries, skydiving, or sticking with Xboxes and PlayStations?”

Enter online sports betting. When Oregonians sign up for the Lottery’s as-yet-unnamed sportsbook app this fall, they’re also unwittingly enlisting in the first phase of a plan to attract and form lifetime gambling habits in a new generation of players.

According to Lehner, sports betting isn’t particularly lucrative for the house. This past winter, Rhode Island’s lottery lost money when the Patriots, predictably, won Super Bowl LIII. But black market sports betting—estimated at $150 billion annually by the American Gaming Association—is wildly popular among fans, a demographic that might not otherwise engage with Lottery products. The prospect of legally betting on a Seahawks game this coming season? Followed by all other major league sports, and, hell, maybe even competitive darts? That’s bound to appeal a number of (ostensibly younger) Oregonians, and then they’ll be in the system, along with their personal data, banking information, and betting preferences—a baseline for the Lottery to track their patterns.

Oregon’s politicians, including Gov. Kate Brown (whose office declined an interview request for this story) have largely been silent on moving the Lottery online. But in Rhode Island, where online sports betting is moving forward despite its Super Bowl debacle, some lawmakers are openly concerned.

“We know cell phones are addictive and gambling is addictive,” Rhode Island state representative Teresa Tanzi told the Associated Press in March 2019. “It’s two corrosive elements together, and we don’t know what those two things together will exponentially produce.”

Shelby says a mobile app can help solve the Oregon Lottery’s transparency problem, and possibly even prove its critics wrong—that its core players aren’t impoverished Oregonians. And having no middleman gives the Lottery tools it’s never had before—opportunities to sell directly, yes, but also to monitor problem playing in real time. Shelby says the new app will contain built-in gates and even “self-exclusion” options for players who spend outside their guardrails.

But will an agency mandated to earn money for the state actively stop someone from betting the store? Shelby hedges, but says the Lottery is listening to fears of vast, mobile-enabled problem gambling. It’s not planning, for example, to adapt Oregon’s notoriously addictive video lottery games for mobile devices. But Powerball, Mega Millions, and Megabucks? They’re coming, for sure; that’s phase two.

Oregon's Game?

If gambling is, as some assert, a morally problematic pursuit for government, the Oregon Lottery has two cards to play. The first is the benefit that Oregonians see from the profits, regardless of whether they play: a new water plant in Lebanon, restoration work on Meacham Creek, funds for every school district in the state.

As director Pack told legislators in 2017, there’s a balancing act built into the Lottery’s founding mission: “to earn maximum profits for the people of Oregon, commensurate with the public good.” It helps, Pack said, to think of the “public good,” in part, as the profits—because they flow to programs Oregonians voted to support. The other part, he acknowledged, is the responsibility to “minimize” one key Lottery byproduct: state-enabled financial ruin and addiction. And one could argue that gambling addiction isn’t much minimized by the 1 percent it gives the Oregon Health Authority each year. (Oregon has an estimated 85,800 problem gamblers, including 4,000 adolescents.)

It’s hard to define a squishy thing like social benefit, especially when weighed against numbers. Luckily for the Lottery, its own documents indicate it’s mostly nongamblers who need that rationale. Once engaged, actual players are more motivated by the “dream of winning” than watershed restoration. (At Ray’s Food Place, Hope Brown just shrugged: “I don’t care where it goes. I don’t believe in where they send it anyways.”)

Which brings us to the Lottery’s second card: personal agency. If a person spends days playing video poker, or habitually risks their savings for a shot at the jackpot? Well, Shelby says, ultimately that’s their call to make.

“One of the nice differences between our revenue stream and other potential streams that the state has, is people make a choice,” he says. “You can choose to play Oregon Lottery games, or you can choose not to.”

On an individual level, that sounds persuasive. But does the state, also, own its agency? For decades, Lottery money has allowed Oregon to operate without the level of tax revenue it’d otherwise need for basic services: education, for one. Keeping taxes artificially low, while raking in discretionary money? Those are wins for politicians. And the promise of more wins, well, that’s addictive. It’s enough to wonder if the house would—or could—ever give up the game.