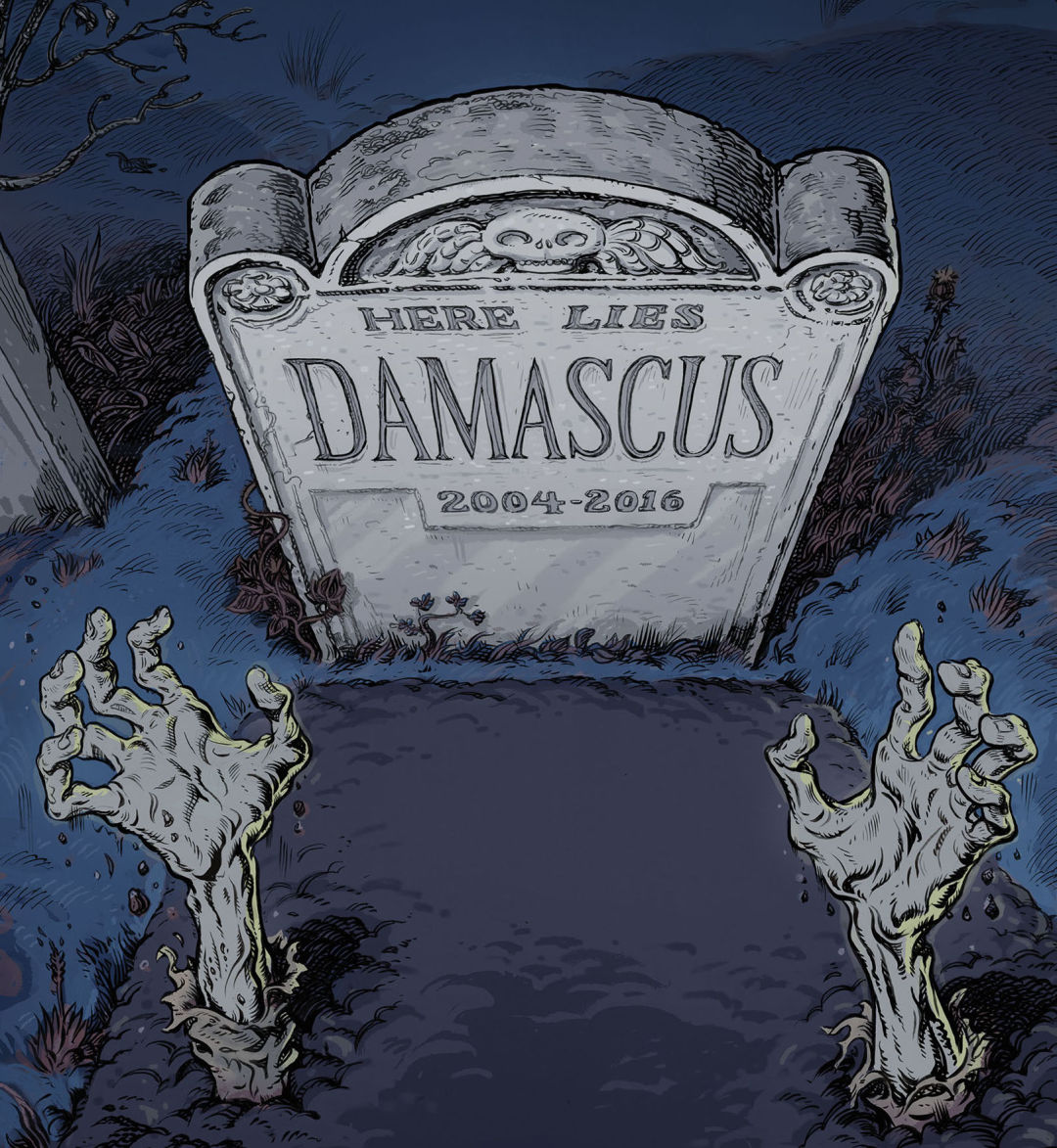

The Curious Case of Damascus, Oregon—The Undead City

Image: Lars Leetaru

Submitted for your approval: can a city be killed? This question haunts Damascus, a place in Clackamas County where politics long ago entered a municipal Upside Down.

This summer, Damascus had a city council that, to many eyes, appointed itself. The mayor conducted business from a church hall and a Starbucks in a Safeway. (There once was a city hall, but now that space is a liquor store.) Meanwhile, not everyone believed he was the mayor—or that there was a mayor at all. Some Damascusites demanded the county arrest the councilors for impersonating public officials. In Salem, the governor signed a bill to dissolve the city, which some locals maintain doesn’t exist. But the church hall and Safeway Starbucks meetings continued. The council adopted a $1.7 million budget to be collected from both the state and the citizens of Damascus—if there is, or was, or will be a Damascus.

“This is a very complicated story,” understates James De Young, the possible mayor. “No other city in Oregon has gone through this.”

“It becomes a question of how many levels of insanity you can deal with,” says Chris Hawes, the leading opponent of the city’s existence.

This does just about defy summary.

Until 2004, Damascus was a semirural, unincorporated swath bordered by Gresham, Happy Valley, and Boring. After Metro brought 10,000 Damascus acres into the urban growth boundary, many hoped becoming an actual city would help Damascus retain some rural character. “We could determine our own density, plan our own parks, and preserve our heritage,” De Young says.

But trouble bubbled from the start: controversial officials, divisive fights over spending and planning, dysfunction. By the early 2010s, some citizens pushed for disincorporation, an exceedingly rare and difficult maneuver. “When you realize that there’s a city you need to make go away,” Hawes puts it, “maybe you should drink a half-gallon of whiskey and forget about it.”

Nonetheless, Damascus voted to disband—twice. First, a state election law quirk required an absolute majority to vote for disincorporation, meaning at least half of all registered voters, vs. a simple majority of votes cast. The legislature passed a bill to let Damascus vote again using a simple-majority rule. In spring 2016, the City of Damascus vanished. Happy Valley annexed significant chunks of ex-Damascus, and its city hall became a liquor store.

But meanwhile, De Young, a member of the last city council, challenged the second election’s validity. Three years later, the Oregon Court of Appeals decided the vote didn’t comply with state law on disincorporation and sent the matter back to a lower court.

De Young saw a clear mandate: “The city was never dissolved, and we never surrendered our charter.” This spring, he rebuilt city council, assuming the mayoralty. (The old mayor lives in what is now Happy Valley, see.) This rebirth prompted a “zombie” headline in the Oregonian (and also inspired our art), a metaphor De Young abhors. “That’s so cynical,” he says. “The better parallel is a newborn baby.” His council’s actions so far do seem earnestly civic. “We’re trying to demonstrate the city’s value,” he says. An August “Coffee With the Council” meet-up focused on neighborhood watch. That same month, the council petitioned the state supreme court to throw out the legislature’s latest

attempt to dissolve Damascus.

To Hawes, the rewind defies logic. “What can you do but get some popcorn and watch?” he says. “You’re fighting a ghost.”

Strange things happen when common understanding of government breaks down. Still, one brave soul thinks some good could yet arise in this tale from the constitutional crypt.

“Damascus,” says De Young, “has the potential to be one of the greatest cities in the state.”