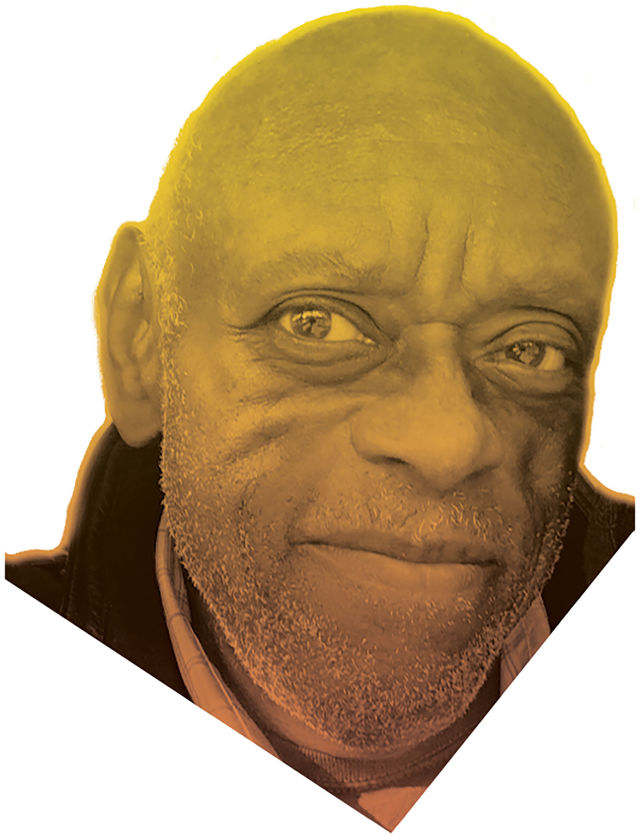

This Portland Illustrator and Activist Has Been Working for LGBTQ Rights Since... Well, Forever

The Brown Bomber is a sweetly innocent, gay superhero. Diva Flambé Touché? She’s the mysterious, wise lesbian who befriends him. Together, this duo has been saving the world since the 1970s and ’80s—the first of their kind when they busted out back then, into a comics landscape dominated by straight, white superheroes. And they owe their existence to local illustrator, activist, and real-life superhero Rupert Kinnard.

Some changemakers helm nonprofits or foundations; Kinnard is less likely to be found in the boardroom than in a living room, striking up a necessary conversation or connecting people. The sexagenarian paraplegic who DJs in his spare time has been living diversity and inclusion since long before they became buzzwords, shaping the state’s gay rights movement along the way.

Born in Chicago, Kinnard moved to Portland in 1979, by which time the Brown Bomber had already made his first appearance in Cornell College's student newspaper. While working as an associate art director at Willamette Week, Kinnard became the first ever art director of Just Out, a bimonthly newspaper that went on to become the region’s largest LGBTQ print publication. “That’s probably one of my proudest accomplishments,” he says now from his home in Northeast Portland, recalling how the paper, which shuttered in 2013, was inclusive and visionary from its inception. It’s also where his beloved comic characters had their longest run.

He joined the board of the Portland Town Council, the first LGBTQ-rights umbrella group in Oregon, in the early ‘80s as its first black member. Through his role there, he founded the Diversity Alliance, a subset of the council aimed at broadening its reach, while organizing fundraisers and forums to explore pressing issues. After one member of the gay community showed up at a pride parade dressed in blackface as Aunt Jemima, Kinnard and others founded Black Lesbians and Gays United. “Immediately [having] that camaraderie, it was like, ‘Oh my god, why didn’t we do this before?’” Some years later, he also helped found the now defunct Brother to Brother, bringing African American gay men in Portland together to share experiences and create community.

In a move that says it all, Kinnard and longtime partner Scott Stapley were among the plaintiffs in a 2008 court challenge to Oregon Ballot Measure 36, which defined marriage as between a man and a woman. “We don’t want to get married,” he says of himself and Stapley. “But we believe in the rights of other people to do it.”

He’s also lent his design talents to newsletters, fliers, and posters for everyone from the National Organization for Women to campaigns against the death penalty, and even the program for the recent Darcelle musical.

A car accident 23 years ago left him “less abled,” and Kinnard now navigates the world in a wheelchair. Yet he refuses to dwell on his losses, and instead honors those who showed up for him at the time, bringing him meals, outfitting his home, celebrating his survival. “That more than anything really fueled my sense of community and how powerful it is,” he says. “When you get that, it increases your need to serve the community.”

It also hasn’t stopped him from throwing dance parties, DJ’ing at a local bar, and hosting a Friday Night Racism Dialogue Group at his home, an ongoing project for more than 13 years now.

“He is the person who makes a difference without making a lot of noise, and who lives out his beliefs in the way he does things,” says fellow LGBTQ activist Kathleen Saadat. “It’s because he wants to see the world be a better place, and he sees his role in it.” The Brown Bomber and Diva Flambé Touché would be proud.

The 15th Annual Light a Fire Awards

6 p.m., November 21, Oregon Convention Center