Editor Therese Bottomly Is Steering the Oregonian into Uncharted Waters

Photo-illustration by Brian Breneman. Source photograph by Jack Liu, courtesy UO School of Journalism and Communication.

In 1983, fresh from journalism school at the University of Oregon, Therese Bottomly arrived at the Oregonian, the newspaper of record that’s older than the state it covers, as an intern on the copy desk.

Construction vehicles still dotted what would become Pioneer Courthouse Square, Rajneeshees roamed Wasco County, and tension flowed from the modern, Pietro Belluschi–designed Oregonian headquarters that occupied an entire city block on SW Broadway. There, reporters from the Oregon Journal, which the Oregonian had bought in 1961 and closed in 1982, worked under the noses of their former competitors in a newsroom rife with fiefdoms and redundancies. It was an era of abundance, though few accolades; the paper hadn’t won a Pulitzer since 1957.

Bottomly, then almost 22, didn’t mind. A self-declared perfectionist and a rule follower, she felt instantly intoxicated by the business.

“You got to start over with blank paper every day,” she says.

Bottomly rose through the ranks, emerging in a period when the paper drew national scrutiny for whiffing on the US Sen. Bob Packwood sex-abuse scandal and, then, national recognition for its recovery under Sandy Rowe, the paper’s first female editor. And Bottomly was there, later, for the seemingly never-ending rounds of buyouts, layoffs, bureau closures, and budget cuts. In 2014, she was publicly passed over for the top job before finally ascending to the editor in chief’s chair four years later.

Now, from her windowless interior office on the fourth floor of an unremarkable Class A downtown tower—the paper downsized from its iconic headquarters in 2014—Bottomly guides what is still Oregon’s largest newsroom, helping to shape the agenda from Salem to city hall.

Frosted glass security doors have greeted visitors since the 2018 Capital Gazette shooting, which killed five staffers at a daily newspaper office in Maryland. From the inside, a spectacular view of the green and red Hawthorne Bridge and snowcapped Mount Hood unfolds over clusters of cubicles. It’s a fitting juxtaposition for an institution that’s both still under threat and dominant in the state.

Bottomly is contending with a declining subscription base, eroding ad revenue, an incredible shrinking newsroom, a late-blooming digital strategy, and a sense that the paper’s heyday has come and gone. She’s finally in charge—but will the institution she’s leading survive?

• • • • •

Warm, extended applause met Bottomly at the all-staff meeting in September 2018 when publisher John Maher announced her hiring as the Oregonian’s next editor.

“All-staff,” of course, didn’t mean what it once did. At its peak in the 1990s, the newsroom employed more than 400 people. It had 185 when the paper’s owners, NYC-based Advance, hired her predecessor, Mark Katches, in 2014. Eight months before the meeting, a round of layoffs—the Oregonian’s eighth since 2010—cost about a dozen more journalists their jobs. Now, only about 65 journalists remained.

Twenty years ago, the Oregonian had a statewide presence and a total paid Sunday circulation of 431,000. By 2019, it had eliminated all of its suburban bureaus and Sunday print circulation had fallen to about 108,000, according to the Alliance for Audited Media.

Bottomly spoke briefly, spelling out her vision for her three priorities: what she calls a “robust” daily news report, consequential watchdog journalism, and coverage of the things Portlanders love, such as hiking and dining.

To reporters in the newsroom, who had watched other talented editors of Bottomly’s rank leave for more prestigious jobs at national outlets, her rise to the top job—from the copy desk to the night desk to the city desk on up—felt like a lifeline. A lifelong Oregonian, Bottomly possesses encyclopedic knowledge of the state’s history and its people. And she is a whiz at unlocking public records from secretive government agencies. Among the most meaningful, she says, was her successful push in the early 2000s to open child welfare records after a child is injured or killed. (Every January, Bottomly still submits a records request to the obscure Oregon Mortuary and Cemetery Board for the list of indigent Oregonians who died, so the paper can update its online database—and families may find lost relatives.)

Colleagues say she brings that same concern and care to her staff.

“Therese is a very confident woman, but also has this magical quality that a lot of the best editors have, which is that she can be ego-less when it comes to the work,” says Anna Griffin, a former reporter, editor, and columnist at the Oregonian who left in 2016 to be the news director at Oregon Public Broadcasting. “She cares about the institution so much, and cares about the people in the institution so much.”

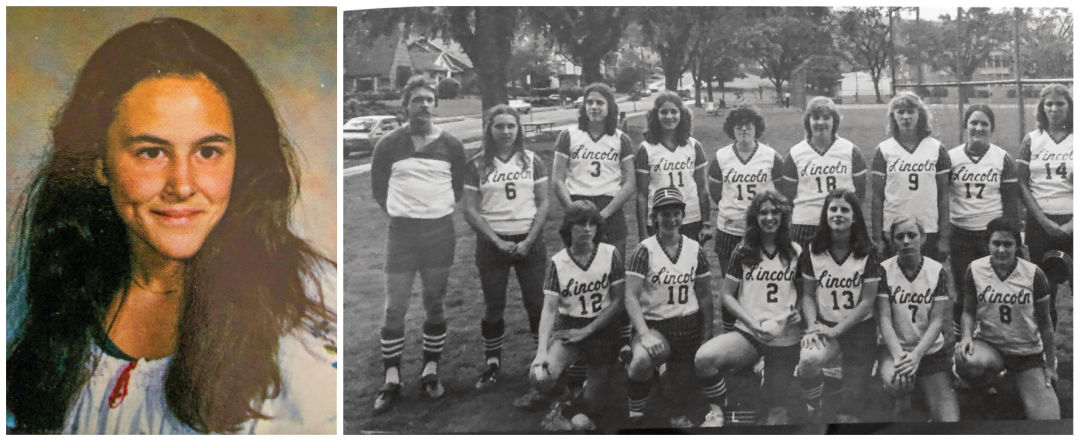

A young Therese Bottomly, no. 8, with her Lincoln High School softball team, and as a high school senior

Image: Courtesy Lincoln High

Growing up, Bottomly counted among her neighbors in Northwest commune dwellers and a barkeep named Bud Clark, who would go on to become Portland’s of-the-people mayor in the 1980s. Her parents were, in some ways, forerunners of today’s hipster culture, limiting TV time for Bottomly and her two siblings (they snuck over to Clark’s house to watch illicit Batman episodes) and installing a pottery wheel in the basement of their Alphabet District home. Bottomly would occasionally encounter Blazers legend Bill Walton on trips to nearby Wallace Park.

She attended Metropolitan Learning Center, where teachers like Lew Frederick (now a Portland state senator) didn’t give grades and encouraged field trips to explore the city.

A top student who craved the A’s to show it, Bottomly transferred in 10th grade to Lincoln High School, where she starred on the soccer field. At lunch she’d walk across SW 18th Avenue to Civic Stadium and watch the Timbers play. “It was an open stadium back then,” Bottomly says. “You could just walk in.” Vera Katz’s son, Jesse, dated her younger sister.

Bottomly’s father, a professor of psychiatry at what was then called the University of Oregon Health Sciences Center, was also diabetic and an alcoholic in the days before either disease was widely understood, and the uncertainty and fear this introduced into Bottomly’s everyday life left her with the lasting ability to keep a cool head in a crisis—as it happens, a highly useful quality for a newsroom leader. Douglas Bottomly died young after going into diabetic shock during a hike in Montana in 1977. He was 46; Therese was 16.

“They pretty much raised themselves from that age on,” says their mother, Phyl, of Therese and her siblings. (Brother Bernie Bottomly is a TriMet executive, and sister Leslie Bottomly is a Multnomah County circuit court judge.) “I swear to God, they just knew what to do and did it.”

Bottomly, who played varsity soccer at UO, was armed with that homegrown self-sufficiency when she arrived at the Oregonian copy desk two days after college graduation in 1983, when pin-up girlie calendars still hung on the walls of the composing room.

“It never really occurred to me that I was walking into a male-dominated [field],” says Bottomly. “I just never thought of myself as any sort of pioneer in that way.”

She did lean in.

John Harvey, the news editor who was her first supervisor, was a fatherly figure in the newsroom. He made sure to give Bottomly opportunities for professional growth, she says, and when he learned she’d been crying in the ladies’ room about a male colleague who harassed her, he busted the guy. The offender eventually landed in the managing editor’s office for a dressing-down.

“She’s smart as get out,” says Harvey, now 80. “She worked hard, worked well, and she knew what she was doing.... I always knew she was going far.”

By the 1990s, very little happened in the newsroom that Bottomly didn’t touch. Under Rowe, who arrived in 1993, she became a “team leader,” then senior editor for news. In the late ’90s, reporter Rich Read had what even he considered a far-fetched idea, to follow a potato from Eastern Washington to its destination as a french fry at a Southeast Asian McDonald’s. It was his way of explaining the Asian financial crisis in a reader-friendly way. Editors rejected the idea, not once but twice. But Bottomly, who had gotten a copy of the pitch, didn’t accept that. She came over to Read at his desk and told him she liked the proposal. Read told her the project was dead, but Bottomly brushed him off. “You watch,” she told him.

A few days later, she walked back to his desk. “Rich,” she said, as Read recalls. “French fries. You’re on.”

In 1999, Read won a Pulitzer for the project, ending a 42-year dry spell at the Oregonian. The paper celebrated by wheeling cases of Champagne and loads of McDonald’s fries into the newsroom.

Twenty-plus years later, Bottomly says she’s learned to be less modest about taking credit for her contributions, a hard lesson learned after she first applied for the editor in chief’s job in 2014 and lost out to Katches, an ambitious investigative journalist who stayed in Portland for four years, then decamped to Florida to run the Tampa Bay Times.

“The experience of going through that one search and then four years later applying again taught me lessons about taking ownership and being less shy about being clear about what your value is and what you bring and what your successes are,” says Bottomly, who in 2019 was one of only five women at the helm of a newspaper in the nation’s 25 largest markets. “I think I was more bold.”

Among her proudest moments so far are 2018’s Emmy-winning five-part video series and stand-alone story, “Ghosts of Highway 20,” its name a nod to the Lucinda Williams album that supplied the soundtrack. The first episode of the series has as its central character not the serial killer who escaped accountability for most of his crimes but the victim who got away, an Inupiaq woman named Marlene Gabrielsen.

The reporter on the story was Noelle Crombie, who followed up the report last October with another blockbuster tale of survival, this time centered on the abused daughter of one of Mercy Corps’s founders.

“At the end of the day, it’s hard to overstate how extraordinary it is to have an editor so engaged and so supportive of something that ambitious at this time of tight resources,” Crombie says of the Ghosts series. “The staff here is smaller. The demands on us are greater than ever. And Therese just never took her foot off the gas on this project. She always saw something big, and she always wanted us to kind of shoot for the moon.”

Still, despite such notable successes, there remains the sense the paper may never recapture the power and influence it once had when it landed with a thud on the doorsteps of one in three Oregon households. “I feel for her,” says Deborah Kafoury, chair of Multnomah County and another lifelong Oregonian. “I dream of the day that Therese Bottomly has the type of newspaper that I had growing up.”

• • • • •

It’s hard to grasp the scale of the resources the newsroom once had that are no longer available. In 1989, for example, the Oregonian chartered a private plane to take half a dozen journalists to California to cover the devastating Loma Prieta earthquake. Nine years later, when school shootings were practically unheard of, a student opened fire at Thurston High School in Springfield. The Oregonian built a remote newsroom at a Springfield Red Lion and installed a phone line that ran directly to the paper’s Portland headquarters. Quinton Smith, the editor who oversaw the operation, said the phone bill for six weeks totaled $32,000.

At the time, Bottomly, then a managing editor, had approved the idea for the mobile newsroom without hesitation: “Do it,” she said, in Smith’s telling. “It was kind of a golden age,” he remembers.

But that was then. Now, one reporter occupies the Oregonian’s Salem bureau, and generally only during legislative sessions. As recently as 2014, three reporters worked there.

Since 1950, the Oregonian has been owned by Advance, a privately held company of the Newhouse family, which owns two dozen newspapers as well as magazines like Vogue and the New Yorker. Another of its regional newspapers provided a cautionary tale last May, when Advance announced it had sold its New Orleans Times-Picayune to an upstart competitor, the New Orleans Advocate. Seven years earlier, the Times-Picayune had served as an early harbinger for changes that later hit the Oregonian, including the abandonment of daily home delivery.

Randy Siegel, CEO of Advance Local, insists Advance’s digital strategy is working overall, though readers have long criticized its oft-scattershot approach. And he says the sale of the Times-Picayune was a “one-off.” “We’re 1,000 percent committed to our existing businesses, and we have zero interest whatsoever in selling any other Advance Local company,” he says. “We strongly believe in our long-term strategy.”

Industry watchers are far less optimistic about Advance’s aggressive drive away from print, although other companies have followed. Locally, that includes the Portland Mercury, which dropped from a weekly to biweekly publication, and the family-owned Columbian in Vancouver, which in January abandoned the Monday issue. But because Advance is a private company, there are few ways to evaluate its claims that its digital strategy is winning.

In New Orleans, public trust in Advance Local evaporated the moment it dropped daily delivery, says Kevin Allman, editor of the Gambit, a New Orleans alt-weekly now also owned by the parent company of the Advocate. Allman, who used to live in Portland, looks skeptically at Advance’s promises to continue investing in the Oregonian. “Their stories have changed so many times over the years,” says Allman. “They could be telling the truth and then revisit it a couple years later. You just don’t know.”

• • • • •

Since Bottomly took over in September 2018, the tide of layoffs has stemmed. And the same three priorities—a “robust” daily news report, watchdog journalism, and Portland favorites—guided Bottomly’s work in 2019. She writes a regular letter from the editor, to transparently explain ethical choices such as the paper’s decision to name certain juvenile defendants or changes such as the use of the singular “they.”

At the same time, on any given day, a clickbait-heavy selection of sports stories and crime capers still dominates the Oregonian’s website. Sample headlines—“Naked jogger on meth who taunted, eluded Oregon cops sentenced to 60 days in jail” or “Portland man who choked his elderly mom, then cracked a beer, gets jail, probation”—point to the nature of online news sources that rely overwhelmingly on advertising rather than subscribers. She’s pushed to shift additional reporters to video production and started podcasting, adopting measures that other similar organizations embraced years earlier.

More significant public-interest stories—on radon poisoning in public housing, pay-to-play politics, the suicide epidemic, and severe neglect of foster children—do emerge, sometimes in collaboration with other newsrooms. They appear alongside lighter stories on Portland’s best burgers or evergreen content listing Oregon’s best waterfalls.

Bottomly says a pay meter is coming soon; meanwhile, in late 2019 she decided to pull the plug on oft-virulent online comments on oregonlive.com.

No one’s promising the dead-tree edition will be around forever. “There will be a print Oregonian as long as it’s profitable,” Bottomly says, echoing the words of the Oregonian’s publisher, Maher. At the same time, Bottomly doesn’t waste time mourning the paper’s diminished horsepower, and says her leaner staff is up for new challenges.

“I’m not afraid to say there’s value in what we do,” she says. “I think Portland deserves a strong, vibrant news organization that reflects [this] vibrant and growing community.”

Beth Slovic was a staff writer for the Oregonian from 2011 to 2013 and has freelanced there since.