Meet Portland’s Biggest Fentanyl Dealer and the Dominatrix Who Loved Him

Back in 2014, Brandon Hubbard and Channing Lacey were in love, living in Southeast Portland’s freewheeling Buckman neighborhood, having sprinted from their problems into each other’s arms.

They hadn’t been together long, and she, at 27, was more than a full decade his junior. But they were settling in domestically, catching movies, and getting frappuccinos at the Starbucks around the corner. Their business was booming, too, enough that Hubbard could put down $15,000 in cash for a Volkswagen GTI.

The nice lesbian couple in the apartment above them had no idea they were running one of the largest fentanyl operations in the country.

Before it all descended into a comedy of errors tinged with tragedy, Hubbard and Lacey used the newest technology to sell a cutting-edge chemical so potent that only two grains of rice worth could kill.

From dark web sites with names like Evolution, web-savvy teenagers ordered the product directly to their doors. Hubbard was the brains of the operation, while Lacey, a boundary-pushing wild child, helped him bag up the shipments and send them out. Flush with dark web profits, Hubbard regularly hit the Bitcoin kiosk at Pioneer Place mall, exchanging cyber currency for cash.

Until it all came crashing down. Addicted to fentanyl themselves, the two started to bungle important details, and the feds came calling. Hubbard’s arrest was a cornerstone in the world’s largest fentanyl investigation, which has stretched on for years. His scheduled testimony this month could finally help put it to bed.

Their saga was the canary in the coal mine, and while prosecutors prepared their case against Hubbard, blaming him for the deaths of two teenage boys halfway across the country, the fentanyl crisis began to swell until it was the worst drug epidemic in American history.

But back then, Lacey had no idea of the investigation’s sweep or her boyfriend’s pivotal place in it. What she did know after Hubbard was carted off to jail was that she’d lost her fentanyl connection and needed a fix, fast. So when she spoke to him on the phone from jail, she had just one pressing question: Where did he bury the tomato?

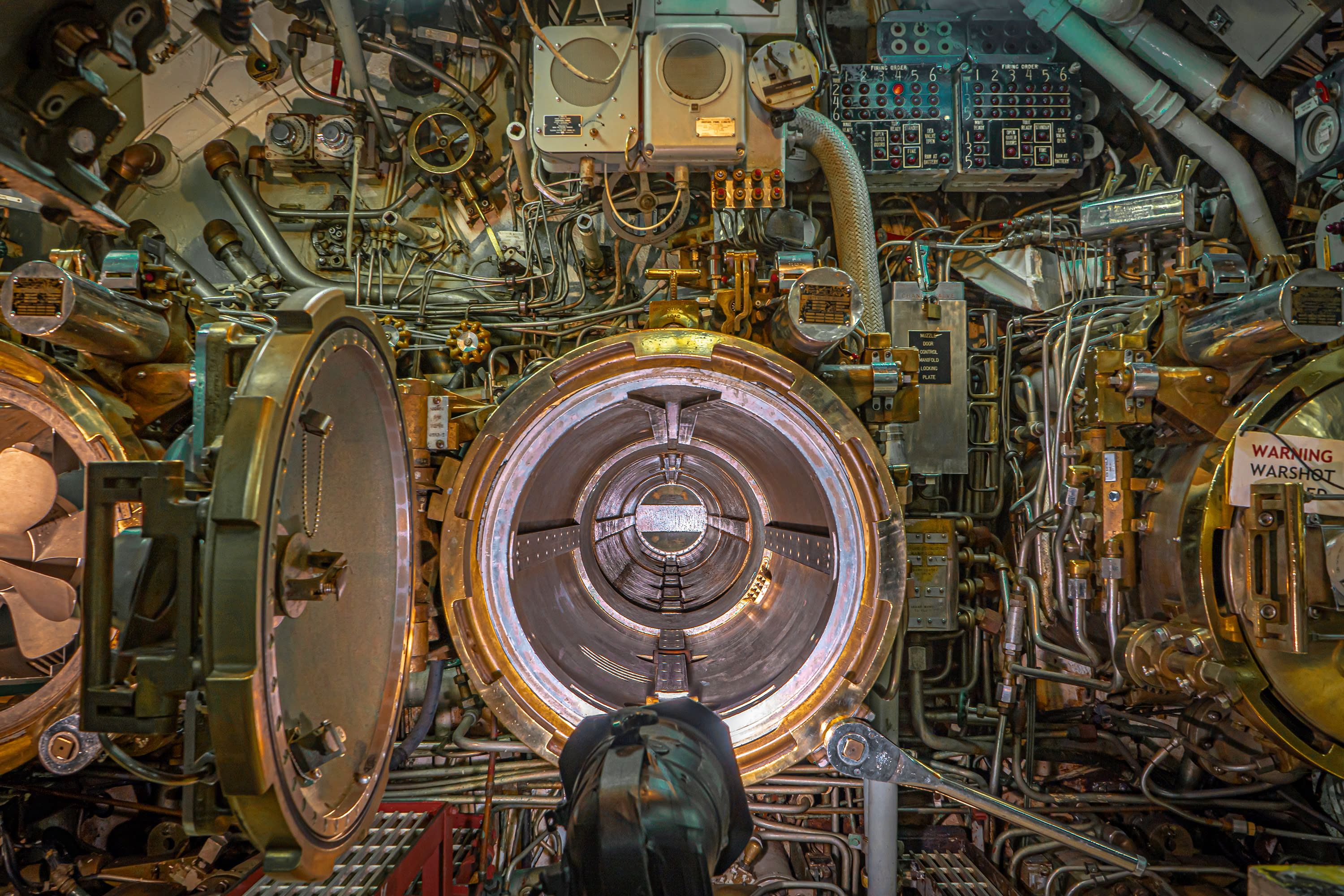

Brandon Hubbard grew up across the Columbia in Washougal. He was a short, scrawny, pale, brown-haired kid whose parents split while he was young. But he made waves as a 108-pound star wrestler at Camas High School—“a really likeable guy,” remembers his coach, Charlie Hinds—and took an early interest in computers and technology. In the mid-’90s he did a stint in the navy and lived in Bristol Bay, Alaska, for a time, fishing king crab à la Deadliest Catch. But it was a 2005 incident in Maui that would shape his destiny: a high-speed bicycle crash into a guard rail that paralyzed his right arm.

“I believe he would have never messed with [drugs] if he’d never gotten hurt,” says his uncle, Scott Conner. For the pain Hubbard was prescribed large quantities of OxyContin for about eight years before being cut off by his doctor. As with countless other opioid epidemic victims, his OxyContin-sparked addiction led him to buy street heroin, which was cheaper and satisfied the same cravings.

He began selling OxyContin for money and then began selling heroin as well; his drug use created a rift with his mother, who has declined to speak on the record about her son.

He met Lacey around 2013 at a dope house in Vancouver, Washington, an apartment that belonged to a friend of Hubbard’s, where just about any chemical under the sun could be had. Lacey was a bespectacled young mother of three with long dark hair covering a tattoo of her youngest son’s footprint on her neck, in the midst of a long fall from grace. Growing up among Mormons in Salt Lake City, she had a childhood filled with dance recitals and LDS church visits (“I hated it,” she says). But after her father lost his job, the family moved to Las Vegas. There, picked on for how she dressed, (“provocative, yet boyish,” she says), she dropped out of high school and dallied with drugs, landing her in the Scared Straight program at the county jail.

Hoping to get away from the drama, Lacey’s parents moved the family to Woodland, Washington, but it didn’t work. Addicted to pain pills after being prescribed Vicodin after the birth of her first child at age 17, she began doctor-shopping for pills and later married a man for his health insurance. She got into meth and heroin.

“I was addicted to shooting up, I was addicted to the lifestyle,” she says. “It was getting really bad.”

She’d long had a penchant for older men, and Hubbard appeared like a beacon. At the dope house he was plying encrypted tablets people could use to buy drugs off the dark web. In an opiate haze they bonded immediately and started shooting heroin together. “I moved into his place right away,” she says. “I just kind of never left.”

Exploiting a friend’s connection, Hubbard sold black tar heroin on the street to support their habits. He soon shifted his business to the fledgling dark web, something of a digital counterpoint to the dope house where he and Lacey had met. Using a disguised internet protocol accessed by special web browsers like Tor, the dark web provides markets vending everything from drugs to guns to child pornography and is difficult to police.

Considering it offers something close to anonymity for buyers and sellers around the world, Hubbard thought it would be both safer and more lucrative than street dealing. But he made mistakes. His vendor name PdxBlack suggested his location, and his password was soon stolen. “[S]ome little punk ... is vending shitty heroin on my account under my name while I am everywhere else trying to build a legitament (sic) name,” he wrote on Reddit in February 2014.

The game changed when a fellow dealer introduced him to a product called China White. “We got an 8-ball of it, and I did a pinhead or maybe a bit more and I overdosed right away,” says Lacey. Yet the overwhelming potency didn’t put them off the drug, which turned out to be fentanyl. “In the drug addict’s mind-set you’re like, ‘This stuff is fucking amazing.’”

Though fentanyl has been used legitimately for decades to alleviate pain for cancer patients and others, in the mid-2010s it began to take off as a street drug. Between 100 and 200 times more powerful than morphine, it is made illicitly in Chinese labs and distributed throughout North America on the dark web or by Mexican cartels. Because it’s incredibly cheap to produce, dealers cut it into heroin and fake prescription pills, passing them off as the real thing. In recent years, deaths from synthetic opioids like fentanyl have accelerated past all other drugs, and they now take the lives of more than 30,000 Americans per year.

Hubbard received his product from a distributor named Daniel Vivas Ceron, a Canadian prisoner. Serving a lengthy sentence for attempted murder and cocaine trafficking, Vivas Ceron accessed the dark web through a contraband cell phone, selling huge quantities of fentanyl to American distributors like Hubbard. To cover his tracks, Hubbard had the shipments sent to his best friend Steven Locke’s Woodland business, Northwest Oil Solutions, which specialized in cleaning tanks and lubricating wind turbines. The money came pouring in.

Hubbard and Lacey lived it up. Though they tried not to be extravagant for fear of drawing attention, they slept in hotels and got the GTI, and Lacey was outfitted in stylish duds. “I had everything I needed,” she says. She even had her own side hustle as a dominatrix. Suiting up in black leather, she would beat men who solicited her services from the internet with whips, step on them with high heels, and dump hot wax on them. The pay was good—$200 an hour—but the assignments became increasingly bizarre.

Once, Lacey says, a real estate agent hired her for blackmail. “She slept with one of her coworkers, and it would have destroyed her life,” Lacey explained. The woman asked Lacey to demand ransom money from her to keep the information secret. “Like, ‘If you don’t give me this, I’m going to call your family!’” She went so far as to give Lacey her family’s phone numbers; apparently, the threat of being caught was enough to excite her sexually. Whatever the case, before this bizarre humiliation could be enacted, the customer disappeared.

By 2015, fentanyl was still unknown to most Americans but was quickly gaining traction on the dark web, and Hubbard’s business surged, earning him “millions,” according to federal authorities. He and Lacey cut the drug with the diuretic mannitol to stretch their profits. In November 2014, Hubbard purchased 750 grams of fentanyl from Vivas Ceron, which had an estimated street value of $1.5 million.

This transaction would prove his and Lacey’s undoing.

Hubbard then sold one gram of the fentanyl on the site Evolution to a Grand Forks, North Dakota, dealer. That dealer then sold 250 milligrams of the parcel to 18-year-old Bailey Henke, a recent high school graduate suffering from an opioid addiction. While playing video games with a friend on January 3, 2015, Henke overdosed and died.

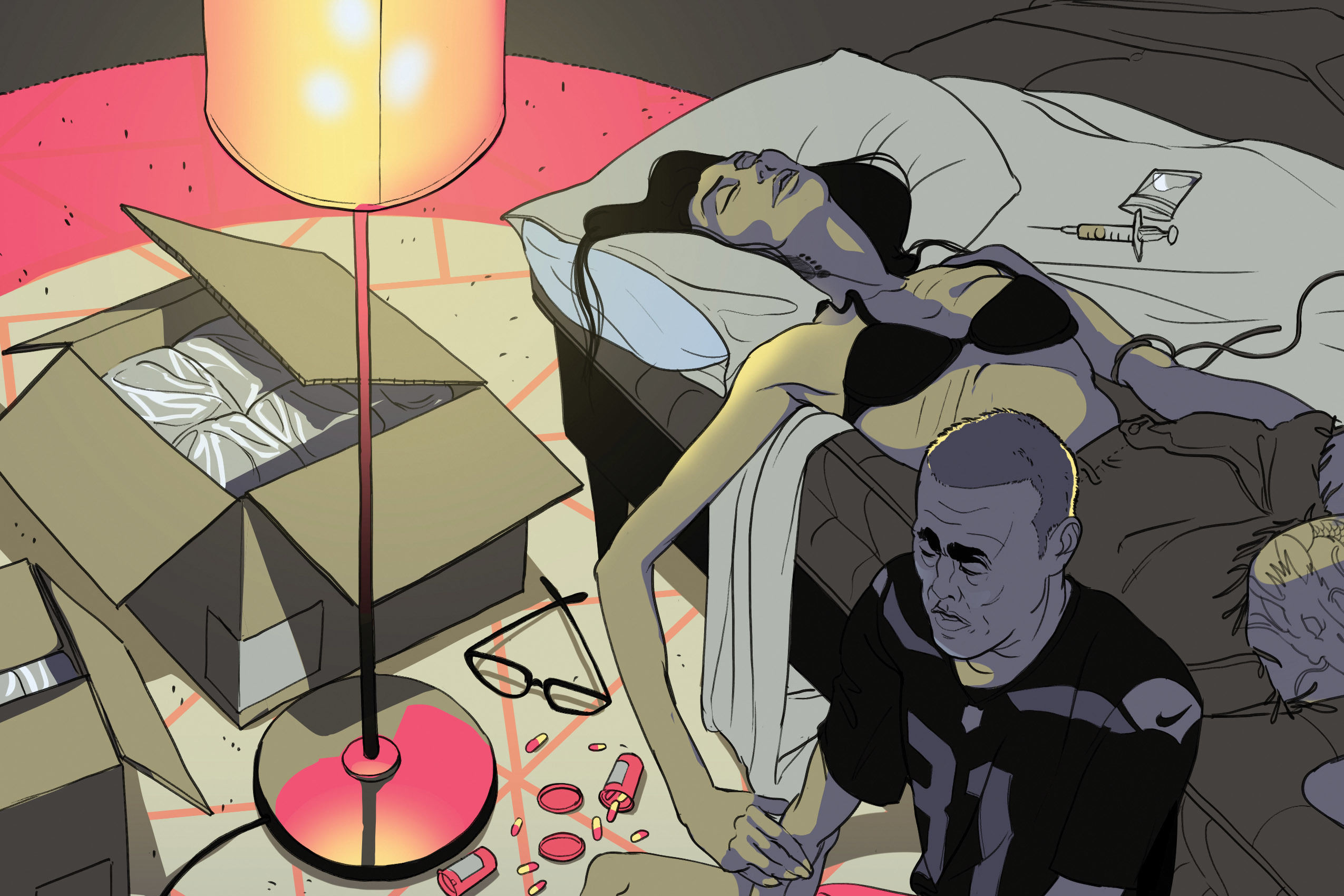

Image: Ryan Garcia

Fentanyl has killed celebrity musicians including Prince, Tom Petty, and Mac Miller, as well as tens of thousands of other Americans. Henke was not famous, but his death made him a cause célèbre in his frozen North Dakota town, one unused to drug casualties. His passing—along with that of another Grand Forks teen just a few months earlier—inspired town meetings, documentaries, and, ultimately, the biggest fentanyl investigation in history. Ranging from Canada to the US to China, the investigation, known as Operation Denial, targeted offenders at every rung of the drug supply chain that killed Henke. Officers seized the drugs and laptop of the dealer who sold Henke the fatal dose and, through the dealer’s Evolution account, uncovered his correspondence with Hubbard.

There would be more bumblings and stumblings before Hubbard was brought in, however. Correctly suspecting law enforcement was on his tail, he began taking the long way home, driving in circles to shake them. This tactic didn’t work, but there was another problem: Hubbard’s car was stolen before they could arrest him. “The car thief, thinking the baggie he found in the vehicle was cocaine, shared the drug with three friends,” reported the New York Times Magazine. Unfortunately, it was fentanyl, and all four overdosed. On January 22, police finally raided Hubbard and Lacey’s apartment, arresting Hubbard and seizing all of the drugs on their property.

All the drugs, that is, except a plump, tomato-shaped baggie of fentanyl, wrapped in duct tape and buried outside their apartment by Hubbard. Lacey, not yet under arrest but panicking and in a state of withdrawal, waited until night fell before plunging a shovel into the earth. Having no idea where the package was buried, she began digging up the surrounding yard like a gopher, still empty-handed 100 holes later.

Lacey next undertook a risky gambit, attempting to subtly coax the tomato’s location out of Hubbard in a jail phone call, knowing full well authorities were listening in. “Brandon’s favorite vegetable was a tomato, and I thought he would understand that was code,” she says. “So I was trying to ask, ‘What window was the tomato out of?’ and ‘How fucking far down are the tomatoes?’ I got tired of sitting outside at night, digging up holes.”

Somehow he communicated the exact location, and Lacey dug up the drugs. Overjoyed yet expecting to be taken by police at any moment, she hid a small baggy of fentanyl in the most secure place she could think of: her vagina.

Her paranoia proved prescient, and she was soon pulled over on a traffic stop by Homeland Security officers, who asked, “Where’s the fucking tomatoes, Channing?” They discovered some fentanyl in her purse, yet as she was booked at the Justice Center Jail she avoided a full cavity search.

In early March 2015 she gave a portion of the baggie’s contents to an inmate who distributed it to others inside the jail, resulting in three overdoses. Dogs were brought into the women’s dorms, all prisoners in the 200-person-capacity jail were strip-searched, and Lacey was thrown in the hole. Yet she somehow maintained her stash, some of which she traded for a Little Debbie Honey Bun with a woman who promptly took the fentanyl and died. Now Lacey knew she was in trouble, and when she heard guards knocking, she swallowed the rest of her fentanyl—three full grams—which sent her into seizures. Since she’d been using such large quantities her tolerance was high, and her heart continued beating. “It took me a week to start detoxing,” she says. “That’s how much fentanyl I ate.”

Hubbard and Lacey now have nothing but time to remember their run as Portland’s outlaw first couple, the drugs that overtook them, and the lives they ruined. In March 2016, Hubbard pled guilty to money laundering and two drug charges resulting in death, receiving life in prison. He is currently being held in Grand Forks and is likely to testify in the April trial of Pawtucket, Rhode Island, resident Steven Barros Pinto, accused of helping organize the fentanyl ring Hubbard was a part of.

“There were some extenuating circumstances, but in the end it was me,” Hubbard told the court. “Being a drug dealer is not something I aspire to. I hurt a lot of people. I’m truly sorry for that.”

Lacey could have gotten off easy with just a fentanyl possession charge, but after smuggling the drugs into jail she received 11 years and change for distribution resulting in death and is now incarcerated in a Minnesota federal prison. The love between her and Hubbard lingers in the midwestern ether.

“I miss him,” she says, adding that she’s legally barred from talking to him. “There are times I’d like to know how he’s doing, but I think it’s just best that we don’t contact.”

Lacey’s mother now cares for Lacey’s two boys while her youngest, a girl with autism, has been adopted. Lacey is consumed with regret and hoping to someday win back her kids’ trust. She’s preparing for a healthier, more productive second act. Her drug addiction has been replaced by an addiction to working out, she has received her GED, and she’s hoping to undertake a prison horticulture apprenticeship.

When she gets back to Oregon, she says, “I want to grow my own herbs and stuff.”