What If You Solved the Zodiac Killer Mystery and No One Believed You?

“Jordan?” I feel a tap on my shoulder. Once I confirm I am indeed the writer who asked him to meet me here, at a well-distanced two-top outside NE 28th Avenue German beer bar Stammtisch on a crisp fall day, the man hands me a small cellophane package.

“Here, I brought this for you,” he says in the quick, deep voice of a former radio announcer. The package contains a customized face mask, flecked in arcane symbols, handwritten in black letter notation. Even inside the plastic, I know these images: it’s a 50-year-old cipher code from the deranged mind of a murderer, remade into the grand totem of 2020. In the center of the mask sits the unmistakable crosshair mark of a pistol, blood red.

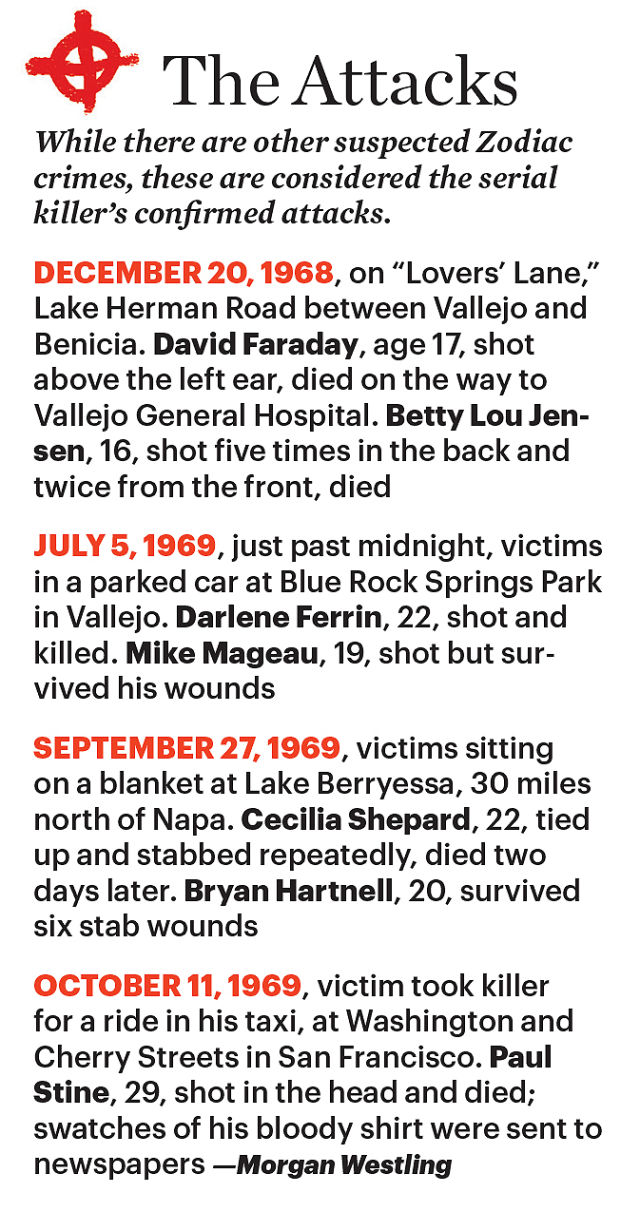

It’s a little jarring to meet an internet legend in person, kind of like viewing a comet through a telescope and realizing the great ball of fire is just a cluster of rocks. This is Tom Voigt, founder and publisher of ZodiacKiller.com, a website he’s run from Northeast Portland since the late 1990s. Its focus, and the source of Voigt’s notoriety, centers on the series of late 1960s murders clustered around the San Francisco Bay Area. Perhaps the single greatest unsolved string of serial killings in American history, the crimes were followed by taunting phone calls and cryptic letters sent to newspapers throughout the Bay Area. The bizarre communiqués included threats, pieces of victims’ clothing, and haunting cryptograms, only one of which had ever been conclusively deciphered until 2020, when a second cipher was cracked by a team of citizen detectives and confirmed by the FBI. The case remains open in multiple jurisdictions, including Napa and Solano Counties, the cities of San Francisco and Vallejo, and under the wider oversight of the California Department of Justice and the FBI.

The killer demanded newspapers run his cipher codes on the front page, whipping up a frenzy of fear. The victims of the self-declared Zodiac were not just those who lost their lives, but the entire region, even the nation, horror-struck by a killer who behaved more like a terrorist. He goaded and provoked police and the public, threatened schoolchildren with mass shootings and improvised explosives, and swore to never stop killing innocent victims, an act the Zodiac justified as “collecting slaves for the afterlife.” Against the backdrop of the Vietnam War and societal upheaval, the Zodiac Killer dominated headlines and nightly news reports around the country.

And then he disappeared. There are no confirmed Zodiac crimes after October 1969, and no confirmed letters after 1974. Suspects included a basement-dwelling ham radio operator, a man hospitalized for schizophrenia, a less-than-honorably discharged navy vet, and practically anyone with a crew cut and glasses, as seen in police composite sketches (including, recently and jokingly, US Sen. Ted Cruz). The killer left behind a daisy chain of bread crumbs and clues, suppositions and theories.

Says Voigt: “Searching for the Zodiac is a work in progress.”

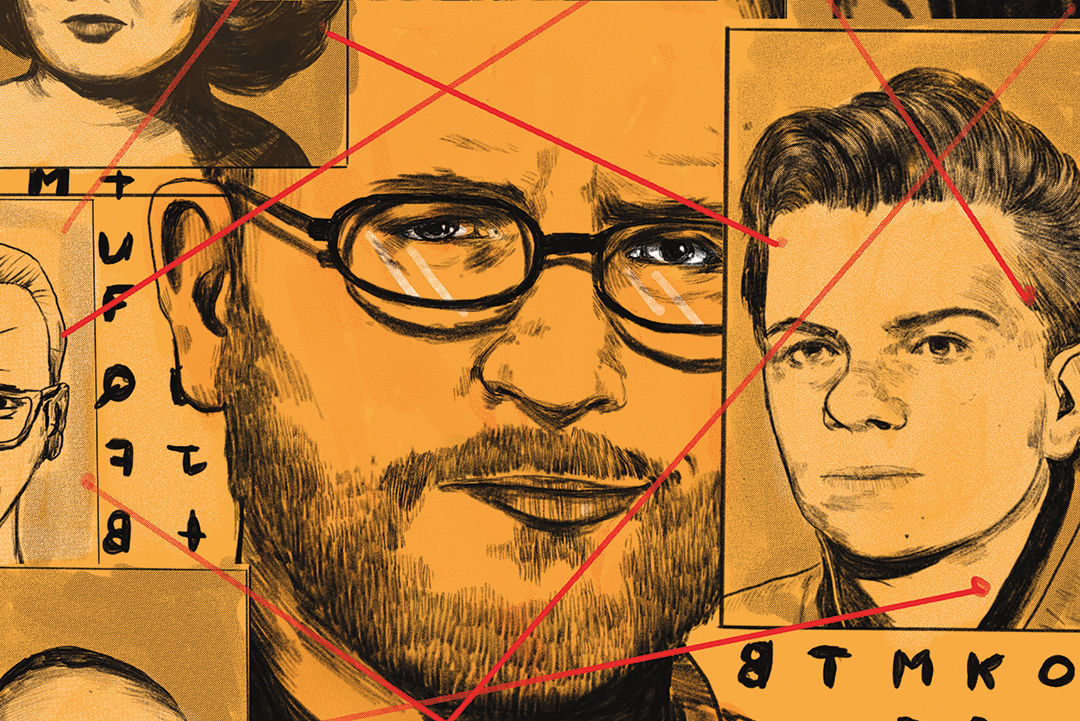

Voigt, 53, looks a bit like Seth Rogen, down to the ever-present baseball cap. He was born in Southern California and moved to Oregon as a kid. He studied journalism and radio broadcasting at Mt Hood Community College and classical guitar at Lewis & Clark, and worked for CBS Radio and KUFO as a morning drivetime announcer. He launched ZodiacKiller.com in 1998 out of an apartment off NE Broadway, constructing the site entirely by himself from a basic knowledge of HTML design.

He recalls no single impulse for starting the website, beyond pure curiosity. “I needed to know who the Zodiac Killer was,” he tells me. “I figured if all the information was in one place, people could work on it.” His timing was fortuitous: as the internet exploded into family homes and portable devices at the dawn of the 21st century, Voigt’s site became a one-stop shop for investigating one of the greatest mysteries of the 20th. It was the first place to publish the mugshot of one of the leading suspects, Arthur Leigh Allen, a lifelong Vallejo resident with a dark past. (Allen is still a viable suspect, though fingerprint and DNA evidence makes this a point of great conjecture.) The case, like Voigt, was just 30 years old then, and his investigative work quickly attained a kind of early version of “going viral.”

“John Walsh mentioned the website on an episode of America’s Most Wanted,” Voigt remembers. “That was pretty cool.” Voigt was later brought down to San Francisco by the program to help stage reenactments for an episode focused on the Zodiac: “It was like a Zodiac vacation.”

Image: Michael Novak and Morgan Westling

Soon Hollywood came calling: David Fincher, the true crime–obsessed director and producer responsible for Se7en and Fight Club (and later the Netflix true crime series Mindhunter) tapped Voigt as a consultant on a new movie, titled simply Zodiac. A near-three-hour psychological thriller starring Jake Gyllenhaal and Robert Downey Jr., the film is based on the works of former San Francisco Chronicle cartoonist Robert Graysmith, who is portrayed as a flawed but brilliant citizen detective, a man consumed by the case as his personal relationships disintegrate. The theatrical posters—in which the word Zodiac appears hovering in fog above the Golden Gate Bridge, a ghostly crosshair in place of the letter “O”—appeared with the dagger tagline: “There’s more than one way to lose your life to a killer.”Other media appearances—over the years he’s been featured everywhere from Coast to Coast AM to Mystery Quest to Vice, io9, Buzzfeed, and Time—and a measured approach allowed Voigt to build trust and credibility with police investigators and detectives, including Ken Narlow, a Napa County Sheriff’s detective who worked the Zodiac case for decades. Voigt talked himself into evidence rooms and interview sessions, keeping meticulous notes, making photocopies, and publishing it all on his website. Traffic kept growing, and reader support allowed researching the case to become Voigt’s full-time job, a professional hybrid that’s part internet entrepreneur, part citizen detective.

“As soon as the advertising began for the Fincher film—the radio and TV spots—my hits started jumping,” says Voigt. “We went from 1.1 million visitors a month to 37 million uniques for the month of March 2007 [when the film was released]. It got so busy my server couldn’t calculate it.... It was off the charts.”

I was one of those unique visitors, refreshing Voigt’s forums and mainpage each night on a creaking old desktop computer decommissioned from my father’s law office, chain-smoking clove cigarettes (2007 was a different time) and scaring myself silly. It felt like sneaking off with my dad’s old Ann Rule paperbacks again. I saw the film opening night, then sped home to read the discourse on Voigt’s forums. ZodiacKiller.com became a constant companion to me in those days, so commonly visited that my web browser filled in the rest—all I had to do was type the letter Z.

There are several competing Zodiac sites, it turns out, each with their own approach and take on the case, and many of them are avowedly anti-Tom Voigt. Some of this is driven by jealousy (at least, according to Voigt). “When my site was featured on America’s Most Wanted, it broke a lot of people’s brains,” he says. “It made people jealous. People had their own websites and were looking for exposure, and they were mad at me.”

To research the true crime subculture around this case is to dip one’s toes into a cold, vast ocean of ruined relationships and online word wars, playing out across the years in the public square of the internet forum. “I keep a list of people who have called me a liar,” Voigt tells me as we wait for our beer, “and every time I’m proven right, I let them know.”

Voigt is a pugnacious and adversarial internet commenter. He fights out perceived slights in real time, when and where they arise, be it on his own website or on sites like the official Reddit Zodiac Killer forum. “Moderation has always been important to me, and if you look at that Reddit, anything goes.” Not so on ZodiacKiller.com, where Voigt will ban dissenters or perceived trolls.

Few things seem to set off those dissenters more than the naming of a suspect, as happened in 2008 when Voigt started zeroing in on one figure, the man he’s now convinced is worth a serious reappraisal by law enforcement, the name he’s put at the top of the list of suspects on his website, in bold red type: Richard Joseph Gaikowski.

Born on a farm in rural South Dakota to Catholic parents, Gaikowski—who went professionally by Dick Gaik—served as an Army medic and dabbled in Dakota politics before moving to the San Francisco Bay Area in 1963. He was a reporter and editor in the East Bay, and then worked briefly at a paper in Albany, New York, before moving back to San Francisco. In 1971, he was involuntarily committed to the Napa State Mental Hospital by his colleagues at a hippie newspaper. He was later diagnosed with an unknown mental illness and treated at San Francisco’s Mount Zion Hospital. He would go on to operate a storefront independent movie theater in the Mission District. In the 1980s, he managed punk rock bands and advocated for marijuana legalization. He died in 2004.

He may have been the Zodiac.

Gaikowski’s time at the Martinez Morning News Gazette put him in close proximity to the Lake Herman Road and Blue Rock Springs crime scenes, obscure backroads known only to locals and just minutes from Gaikowski’s apartment. He covered a jailbreak at Lake Berryessa with eerie similarities to the eventual Zodiac attack. When he returned from Albany, he took the helm at a short-lived Haight-Ashbury alternative weekly newspaper, the San Francisco Good Times. The paper used a home at 1830 Fell Street as a “switchboard”—a kind of predigital place for messages to be sent and received, as well as goods to be picked up or dropped off—located mere yards from the home of eventual Zodiac victim Paul Stine. Four days before Stine’s murder, Good Times hosted a book collection drive there. The story about the event was bylined by Gaikowski.

Stine’s sister, Carol, told Voigt she recognized Gaikowski as having attended her brother’s funeral. A sister of victim Darlene Ferrin has claimed for decades that one of her sister’s former boyfriends was a journalist named Richard. In the 2008 documentary This Is the Zodiac Speaking (released as a bonus feature on the Blu-ray version of Fincher’s film) victim Mike Mageau, who survived the same attack in which Ferrin was murdered, describes being chased by a man just before: “I thought he drove off and drove away, but he came back later and shot us. She told me it was a friend of hers and he was just jealous. She mentioned his name—she referred to him as Richard.”

Nancy Slover, the police dispatch operator who took a call from the Zodiac immediately after the Ferrin-Mageau attack, heard an audio recording of Gaikowski’s voice in 2009. “I listened to the voice of Richard and felt shock and déjà vu,” she told Voigt’s site and the 2008 documentary crew. “In my opinion, he was the same person I listened to in July of 1969.”

Image: Nicole Rifkin

Gaikowski was brought to Voigt’s attention by Blaine T. Smith, who has been known professionally and personally as simply “Blaine” or “Blaine Blaine.” Blaine was part of the Good Times newspaper collective alongside Gaikowski. Wildly intelligent and intensely complicated, Blaine appears trim, small, and wigged in photographs and rare film clips. They are still alive, 84 years young, and posting regularly to Facebook from a small town in New Mexico. I contacted Blaine but was unsuccessful in speaking to them as of press time—but not because they’ve gone silent.

“Blaine has more energy than I did as a teenager,” Voigt tells me, who has interviewed Blaine over the years across a series of multihour phone calls and occasional in-person meets. Blaine “speaks in references to poets and historical figures,” says Voigt, noting the amount of information in Blaine’s possession is “astounding.”

This much is known for sure about Blaine: after coming into a large sum of money in the early 1970s and departing for Crete, Blaine returned to the Bay Area in the 1980s and lived out of an elaborately converted camper van. Around the time of the release of Robert Graysmith’s first book about the Zodiac Killer in 1986, Blaine became convinced a former colleague, Gaikowski, was the man responsible for the crimes. Blaine had audiotaped statements and corroborative evidence to buttress the claims. They reached out to authorities, including the FBI and the San Francisco Police Department, and urged them to investigate Gaikowski. With the exception of Ken Narlow—the Napa County detective briefly investigated Gaikowski before having his surveillance efforts scuttled by Ferrin’s sister—the authorities by and large declined. The FBI dismissed Gaikowski after he said he’d been in Europe at the time of the first murder, even though he had “lost” his passport.

On Facebook, Blaine published a 2012 letter sent on their behalf to San Francisco Chief of Police Greg Suhr from Bay Area attorney Jai Gohel, who alleges Blaine was discriminated against by authorities in the 1980s because, in part, they are transgender, and were at that time living in a van and deemed “homeless.” Today Gohel stands by the 2012 letter emphatically: “I know what every asshole San Francisco cop would have thought of Blaine, and there’s no question appearance and orientation played a part,” Gohel says. Blaine was dismissed because of who they were.

Gohel describes Blaine as “sweet,” “interesting,” and an “odd bird.” All three descriptors are on display on Blaine’s public Facebook page, which contains multitudes: pornographic drawings, allusions to the Revelation, and wide-reaching accusations against Gaikowski stretching into the 1980s. They are a complicated person, an imperfect vessel, but there is an overarching theme to nearly everything they post: Blaine is unwaveringly convinced they will be vindicated when DNA evidence and modern police techniques finally name Richard Gaikowski as the one true Zodiac Killer.

Did a witness walk a legitimate suspect into the authorities 30-some years ago, only to be discriminated against because of who they are as a human being? So much more could have been done, might have taken place, were Blaine a different person telling the same story without the burden of transphobia.

What if you solved the crime of the century and no one believed you?

What if Blaine—what if Voigt—were more of a Michelle McNamara kind of figure? McNamara rose to fame in the true crime community through her work on True Crime Diary, an independent website dedicated to solving cold cases. “True Crime Diary is not interested in looking back at notorious criminals and saying, wow,” the site states. “We’re interested in looking at unfolding cases and asking, who?” By 2013, McNamara had zeroed in on the case of the Golden State Killer, whose crime spree in the 1970s and ’80s spanned a series of attacks, ransackings, and murders up and down California. She found a community of online investigators working together to solve the case: retired detective Paul Holes, crime writer Paul Haynes, Billy Jensen, the investigative journalist, and many more.

After some of her work appeared in Los Angeles Magazine, it was quickly optioned into a book-length treatment for Harper Collins. I’ll Be Gone in the Dark was released in February 2018 to international acclaim, on the New York Times best seller list for 15 weeks, with adaptation rights snatched up quickly by HBO. Two months later, police in Sacramento announced the arrest of Joseph James DeAngelo, a 72-year-old former police officer, who would later plead guilty to dozens of counts of kidnapping, murder, rape, and abduction. Though she did not solve the case, McNamara has been widely credited with bringing attention and new investigative resources to the search, ultimately resulting in justice.

McNamara didn’t live to see the Golden State Killer behind bars, or even her book published. She died tragically from complications of an accidental drug overdose and atherosclerosis in 2016; it’s been suggested overwork, late nights, loss of sleep, and utter absorption into the case exacerbated McNamara’s health conditions and relationship with prescription drugs. There’s more than one way to lose your life to a killer.

Her book was completed after her death by Haynes, Jensen, and her husband, the actor Patton Oswalt, working within a true crime community that was helpful, collaborative, and oriented morally toward justice above all else. The events described in McNamara’s book—an online sleuth community coalescing around an investigator, resulting in a final moment of justice, a grand catharsis, a “true crime Christmas” as some called it when DeAngelo was caught—feels like a blueprint for citizen detective collaboration, the setting aside of ego and hubris in service of a bigger purpose.

That’s not what happened with ZodiacKiller.com. When Voigt reintroduced Gaikowski as a possible suspect, running down leads and hinky coincidences, he unleashed a backlash that’s hard to neatly summarize. “Initially, there were some people who were compelled, but others started to simmer and boil in the background,” Voigt remembers. “For every person who was excited, there were those who became spiteful and angry. It was a whole bunch of people acting like children.”

As the din of skepticism grew, Voigt banned doubters at will. Some of those doubters took their grievances to other message boards and other websites, and sought to discredit Voigt in any way possible—including his work on Gaikowski.

“Voigt’s case is trash.”

“Voigt’s vanity and deceit has always got him into trouble with his attention-seeking antics.”

“He’s verbally attacked many here with creepy and threatening PMs.”

“I actually feel embarrassed for Voigt. Imagine being his age and sending these messages.”

These quotes are from a recent Reddit thread (a new section of ZodiacKiller.com is called “FIXING REDDIT,” all caps, in which Voigt airs grievances and refutes misstatements), and are just a taste of the anti-Voigt sentiment accessible with a quick web search. Voigt denies the accusation of sending angry personal messages, but someone is out there defending his side vociferously, lashing out at the doubters and haters.

“I told the same bedtime story every night,” Voigt says, “and it made them feel comforted. But then I broke out this new bedtime story. Some were excited, but others were spiteful and angry, and that’s how I explain it.”

McNamara’s role in the true crime community meant access, support, likeminded investigators pursuing every avenue, and eventually even renewed police attention that led to the closure of the case. When it comes to Voigt, though, rather than argue about the reality of the case or investigate Gaikowski as a suspect, discussions quickly turn to an airing of grievances and ad hominem attacks against Voigt. To an outside observer, it feels like Voigt’s detractors would sooner never solve the case than see his suspect be confirmed by authorities.

Again, what if you solved the crime of the century and nobody believed you?

Back at Stammtisch, Voigt orders a Weihenstephaner—“this is the oldest brewery in the world, you know”—and I ask him if he’s ever been to Germany to experience it firsthand. “I can’t fly anymore,” he offers. “It’s all the 9/11 stuff I’ve been watching. You see those videos over and over again.... Who can get on a plane after that?” Voigt is convinced 9/11 is an active mystery, a conspiracy he says involves the discovery of pools of liquid thermite beneath the towers. I turn the conversation back to Zodiac, but it reminds me of when I met Voigt once before, at a coffee shop back around the 50th anniversary of the Zodiac crimes. I asked him then what he’d do if the Zodiac case were solved conclusively. He told me he’d go search for Bigfoot.

In the meantime, of course, the case and Voigt’s website continue to captivate. Why am I so fixated on the Zodiac Killer crimes? Why did I become hooked on Voigt’s website more than a decade ago, and why do I keep coming back, engaging in my own back-and-forths on Reddit and rereading case files late at night before I fall asleep? I should be trying to sell a cookbook or something (my usual beat is food and drink), not poring over 50-year-old Haight-Ashbury counterculture newspapers for murder clues.

For all his mortal faults, Voigt wants to solve this case. He needs to know who the killer is, not just to prove the doubters wrong, not just to make good on his life’s work, but because he feels it somewhere deep down inside.

DNA might someday solve the case—there is the possibility of deriving DNA samples from the back of stamps on confirmed Zodiac letters—but progress on this front from investigatory agencies has been maddeningly slow. For every true crime Christmas—like the Golden State Killer arrest or the 2005 capture of Dennis Rader for Wichita’s infamous BTK Killings, a series of attacks spanning from the mid-1970s to the early 1990s—there are cases that feel more like a hunk of coal. And DNA has its limits, especially when there was no overt sexual component to the crimes. These were blamm-o shootings, seemingly random murders with no discernable pattern or modus operandi.

Handwriting, footprints, payphone calls, letters to the editors of multiple daily newspapers—the form and shape of this case is driven by 20th century technology. It’s retro; it lives in yesteryear, and has to be approached for and considered in that mind-set. It’s the thing Fincher’s movie gets so right, the all-consuming vibe of it, San Francisco after night falls on the Summer of Love, all creeping dread and lysergic haze, the drone of “Hurdy Gurdy Man” echoing across the fog-draped nights. And yet crime has tragedy at its core, inescapably. I am comforted by one fleeting fact: it can still be solved.

Or the case may be abandoned to history, an eternally unsolved mystery, America’s Jack the Ripper. But the memories of those who lived through the terror more than 50 years ago still have the potential to crack the case. Maybe our fascination will kick over the right rock, rattle the correct cage, and shake some lost evil out of hiding. Maybe someone who knew Richard Joseph Gaikowski—as a journalist in the 1960s, or a movie theater owner in the ’70s, or a punk rock promoter in the ’80s, or in one of his other phases of endless reinvention—will remember something. Maybe that person will reach out to Tom Voigt. Or maybe not.

“I’ve learned a lot about people over the last 27 years,” Voigt says ruefully, “and mainly I’ve learned I don’t like most of them. I don’t even know why some of these people are interested in the case. The truth is, we don’t know who the Zodiac is, and so we have to look. And so I’m looking.”